Tricky Thicket

Audrey hadn’t slept, hadn’t really slept—as in hours uninterrupted by nightmares, sleep that didn’t fracture with the tick of her heart rate and the churn of her thoughts—in weeks. She’d climb into bed, exhausted, maybe even drift off, but it wouldn’t last. She’d wake in cold jolts, certain that someone was watching her. She’d just catch their shadow slink away, eyes not fast enough. Or she’d hear buzzing inside the walls, a humming beneath her pillow. Or a breeze that should carry only the scent of the water would somehow be choked with rotten apple, too.

No, she wasn’t sleeping. And she knew she was now showing its absence. Certainly, she was feeling it. Although Merritt couldn’t be sleeping much, either. It was so dark where their tiny houses were perched that even from her bed—every night, well into the small hours—Audrey could see the phantom glow of Merritt’s laptop.

The small, sleepless hours.

Audrey had been using some of that time to text Noel on the West Coast, where it was much earlier, although soon enough they’d be sharing a time zone. He was headed this way for a New England concert tour, one that would be culminating with a show in Providence, a show she would be attending. (And so would Bo’s cameras.) Brookhants seemed to her now like some massive magnet pulling all parts of her life to it.

Or maybe that was dumb and she just needed to sleep.

This is why, as she now stood at the breakfast bar in Harper’s cottage and watched Eric take several enormous, if wilted, angel’s trumpet flowers from his messenger bag, Audrey started paying attention to his sales pitch: he’d just said something about them begetting deep sleep.

“Yeah, as in indistinguishable from a coma deep sleep,” Merritt had said.

Before they’d left Brookhants for their bonus beach day, Eric had harvested the flowers, and since then he’d been listing their potential medicative and hallucinogenic properties, alternating between what he’d committed to memory and what he read to them off his phone. Merritt peppered this rah-rah with fear and loathing.

The two of them had been arguing—mostly good-naturedly and hypothetically, Audrey had thought—but here, in the tiny kitchen of this tiny house, the strength of Eric’s intent was made much more real. Here were the flowers on Harper’s counter, their sweet scent already emanating. And here was Eric filling her silver tea kettle with water. And here was Merritt picking up his phone and reading the screen and saying, “OK, so to be clear: you’re willing to bet your life on advice given to you by total internet stranger the Shroom Savant?”

“Not only him,” Eric said. “I know it kills you but I too have done my research on this subject.”

“I’m not gonna be the one it kills,” Merritt said.

He Dracula cackled at her.

“This is ridiculous,” Merritt said. She turned around to Harper, who was on the love seat behind her. “Your friend is being ridiculous.”

“All my life,” Harper said.

Eric was now dropping the flowers, one by one, into the kettle. They were so large and delicate and white, he might have been dropping in silk handkerchiefs. He put in three, consulted his phone, and added a leaf from the same tree, honey, and a few orange spice tea bags. Then he put on the lid, placed the kettle on the stove, and clicked on the burner. While he washed his hands at the sink he said, in the voice of a teacher tired of reexplaining a fact, “Like I said, I’m not messing with the seeds or the roots, which are significant points of potency. I’m brewing a mild tea that I will drink only a little of to give me an introductory experience to this plant and its attributes. I have a lot of experience with introductions to substances. I am good at them.”

“Has it occurred to you that maybe it’s a little uncharitable for you to force us to babysit you during your drug trip?” Merritt asked.

“Who’s asking you to babysit? I’m asking you to come along.”

“That’s the thing—nobody wants to,” Merritt said.

“I mean—” Harper said.

“You’re not serious?” Merritt said.

“I am curious,” Harper said.

“Me too,” Audrey said before she didn’t. “The sleep part sounds really good to me.” Harper smiled at her.

Merritt did not. “Not to me,” she said. “No part of me. Are we going in the water?”

“I am,” Harper said.

“It will be freezing,” Merritt said.

“I’ll keep you warm, girl,” Harper said.

“Significant eye roll,” Merritt said. That’s what she said, Readers. I’ll leave it to you to determine what she felt.

“I’ll meet you down there,” Eric said. “As soon as it’s ready.”

“Take your time,” Merritt said. “Take all the time.”

And so they left him at the stove brewing a flower potion in a tiny cottage by the shore.

There was something to the three of them walking the same wooden stairs down to the beach that Libbie and Alex and their sapphic squad had walked all those years before. Not the same, the same, of course—over the years boards would have been replaced, likely many times, salt water is so hard on things—but the path they took, the quality of the light, the roil of the waves: it was the same enough and there was something to it.

They spread their towels on the strip of sand, avoiding the stinking piles of seaweed and things washed ashore. Audrey had assumed they would sit for a while in the sun, talking or not, but looked up to find Merritt and Harper shedding their outer layers of clothing, down to their bathing suits. Audrey never went about things this way at the beach. She was not the type to immediately plunge into the water. She liked to acclimate, to take her time. But right then she needed to be a part of whatever they were doing.

They as in the three of them, the three of them together.

They walked in up to their ankles, the cold water aching their bones, all the way through their bodies to the roots of their teeth. It was freezing. And the floor was sharp with shells and stones. They went in a little farther, up to their knees, gritting their teeth. It was too cold and yet there they were in it. Smiling.

Harper did it first—crashed under the roll of a wave. Then Merritt. Then Audrey. The cold sucked away her breath. She’d forgotten how salty it was. She always managed to forget that.

They screamed from the cold, a tangle of seaweed in Merritt’s hair until Audrey plucked it out and flung it at Harper. They came alive in this water. They had to—how else could they bear it? Splashing and dunking, touching each other freely because for now they were only playing in the surf like children. There was no weight to this kind of touching. It was open and easy, reciprocal, wanted and without agenda.

Above them loomed Spite Manor, and above it loomed its strange tower, that single arm blocking the sun and casting a long dark shadow down the terraces and over the rocks. But for now, they were happy on the beach below.

Time had become very slippery.

When they saw Eric on the stairs, they crashed out of the surf and back to their towels, their lips drained of color, their skin cold to the touch and rippling in goose bumps from the breeze. Eric was carrying a thermos and wore the proud smile of a parent at a dance recital.

“You’re mermaids,” he said. “And I’ve brought you an offering.”

They formed a dripping knot around him as he twisted off the lid and steam rose from the container, along with the heady scent of angel’s trumpets steeped in honey.

“Are we doing this?” Harper asked.

No one answered.

For a few moments, they stood in that knot and let the sweet steam swirl between them. Then Eric tipped the thermos to his lips and drank and swallowed and then once more. He passed it to Harper, who did the same, and then Audrey did so as well, when it was handed to her. Still no one had spoken.

Audrey offered the thermos to Merritt. She held it before her, looked down into its mouth, and said a thing that was, just then, the only thing that could be said. The words were Mary MacLane’s: There is something delirious in this—something of the nameless quantity.

And then Merritt took a long drink. She passed the thermos back to Eric, who walked the few feet to the water and poured what remained into the bay.

“I’m surprised,” Audrey said to Merritt.

“I didn’t want to be left out,” Merritt said. “I might already regret it.”

“None of that,” Eric said, walking back to them. “We have to set our intentions now for the experience we want to have. If you launch your ship in negativity, you’ll spend your trip that way.”

“So deep,” Merritt said. “Deepak Chopra deep.”

“There she is,” Harper said.

“How long will it take?” Audrey asked.

“No idea,” he said. “An hour?”

“How long will it last?” Harper asked.

Eric shrugged. “I mean, nobody drank very much.”

“Oh Kind Devil,” Merritt said. “What have we done?”

From a tall tree in the woods, a flock of birds lifted. They were noisy with their calls and the beat of their wings. This as the wind skipped over the water. Our heroines shivered.

“Is it worth getting in?” Eric asked them, tilting his head at the churning foam.

“It’s freezing,” Harper said.

“I know somewhere that’s not,” Merritt said.

Back at their houses, they provisioned quickly. Eric insisted they bring drinking water, so much drinking water, because they’d need it. Dry mouth was, he promised as he loaded a canvas shopping bag with bottles, a guaranteed side effect. He also recommended chocolate to enhance their experience. Merritt said they’d want real shoes, not flip-flops, for their trek through the woods. But they kept their swimming suits on.

Audrey thought she’d like to sink into her bed and stay there, but she’d like it even better if the others stayed, too. If they all took a long, lazy, afternoon nap while they waited for the tea to do its work. Maybe by then, when it finally kicked in, it would only serve to keep them in sleep, throughout the rest of the day and night and on into morning. She would have liked this best.

But there was a message on her phone—on her new, nonbroken, production-provided phone—from Bo: Try to get Merritt talking about the Rash brothers. Also, flat rocks—you’ll see them—are best for hanging out once there. Good angles. Please drink water! Lots!

They walked two by two, Harper and Eric trailing behind Audrey and Merritt.

Audrey held her hands out to her sides and let her fingers brush the reaching tips of the tallest ferns. She listened to the way their footsteps fell. She listened to the way Merritt breathed next to her. She tried to decide if she was already feeling something from the tea, but she couldn’t decide and anyway, Eric said it was too early for that.

They’d hit one of those patches where cell service decided to work, and an explosion of notifications landed on Harper’s phone. She stopped to scroll and Eric stopped with her, but Audrey and Merritt kept walking, letting the gap between their foursome grow.

Audrey worked on a Rash brothers question, a lead-in that wouldn’t announce itself as such, but it was Merritt who spoke first. “I thought Bo’s Hepburn impersonation was unnecessary. Earlier.”

Audrey was almost as surprised by this offering as she was by Merritt drinking the tea. “Yeah?” she said. “Maybe. But his point was valid.”

“Was it?”

“I think so,” Audrey said. “When I listened back, some definite cringe moments. There was so much else going on this morning with the delays, I wasn’t focused the way I needed to be. I wasn’t Clara, I was playing Clara.”

“Is that really how it works for you?” Merritt asked. “That’s what it feels like?”

“When it doesn’t feel like anything is usually when it’s going well,” Audrey said. “But Clara Broward has a confidence I wish I had, so maybe I’ve been trying too hard to project that. I’m sure I have been doing that.”

“For what it’s worth,” Merritt said, “for the very little it’s probably now worth to you—I’ve been thinking the last few days that you suit her.”

“It’s not worth little,” Audrey said. “Thank you.” She almost didn’t say the next thing but this afternoon, thus far, felt so peaceful to her. Easy. So she did say it. “I got the sense you weren’t my biggest fan. I mean back in LA.”

“Yeah, I act like that sometimes and then regret it after. I’m sorry. It wasn’t really about you, if that helps.”

“I think it was about me, actually,” Audrey said.

Merritt smiled. “Yeah it was. But I’ve grown up since.”

“What, are angel’s trumpets a truth serum, too?”

“You joke,” Merritt said. “Will you do me a favor?”

Audrey laughed in surprise. This she really wasn’t expecting. “I mean, maybe,” she said.

“If this gets intense, or if you feel like it’s too much—or if you think I do, but I won’t say it—will you stay with me? I know we’re all together, but Harper and Eric have their whole history, so . . . will you be my trip buddy?”

“Yes,” Audrey said. “If you tell me something.”

“Oh God. What?”

“I’m sure it’s not whatever you’re thinking,” Audrey said. “I wanna know—I mean, I’ve been thinking about it and wondering why you didn’t put the whole story of the Rash brothers in the book, like not just as a footnote?” She felt a little guilty about using what had been a nice moment of connection between them to do Bo’s bidding. But only a little.

“I think it’s generous to have even given them footnote status. I don’t care about the Rash brothers. Fuck the fucking Rash brothers!” Merritt now shouted into the trees.

Audrey laughed. That was enough for her. She didn’t care if Bo wanted to hear more about the Rash brothers. She didn’t.

Harper and Eric came charging from behind. “Who are we fucking?” Eric yelled.

“The Rash brothers!” Merritt yelled back.

“Oh, those cunts?!” This from Eric.

Were they feeling the tea now? Audrey tried, again, to tell if her reality had altered. She couldn’t say for certain. It might have been the sunlight through the leaves and the scent of pine pitch and the permission granted by having an afternoon to do something like this in just the place for it. It might have been her lack of sleep.

Merritt pointed to the left, where, in the distance, there was a noticeable density to the understory, the brambles bramblier. “That’s it,” she said as she started in that direction. “Part of it.”

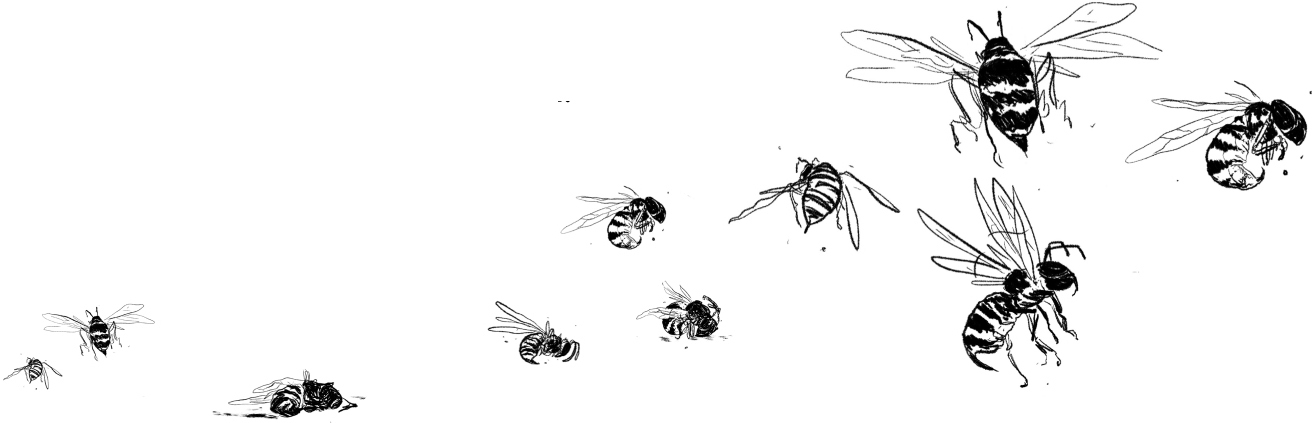

“I mean, hold off on the mockery if you can, but should we be at all worried about yellow jackets in here?” Audrey asked.

“Probably,” Merritt said, pulling back a branch to help them clear the entrance.

Audrey was the last one through and just after, her shirt was snagged by something. When she turned to look, she saw it was the thorny arm of a blackberry bush clustered with ripe berries. She picked and ate one and it was so sweet and fat with juice, so perfect an experience, that she did not want to pick and eat another and be disappointed by it.

Merritt and Harper were examining a stand of delicate pink flowers on thin stalks, which Merritt, of course, identified as “lady’s slippers—a kind of wild orchid.”

“I see lungs,” Eric said.

“I see vulvas,” Harper said.

“Oh, I’m switching to yours,” Eric said.

“It’s not a Rorschach,” Merritt said.

“Everything in the world is a Rorschach,” Eric said.

“Do you feel anything yet?” Audrey asked them.

“Maybe,” Harper said. “I can’t tell. This place is a trip on its own.”

“You don’t,” Eric said.

Audrey couldn’t help herself: she took another blackberry. Actually, she took several from the same cluster, popped them in her mouth and crushed her teeth against their ripe flesh. They were just as sweet, just as good.

They continued on, slowly, picking through bushes and pulling back vines, until Merritt said, “Here.”

She knelt on a bank so thick with moss it might have been a sheet of green velvet, her hand tipped below the ledge where Audrey couldn’t see until she came closer and saw the bend, the pool, the feathers of algae—Merritt’s fingers floating among them like fish.

“I think we’ll all fit,” Merritt said. “Mostly.”

There were the flat stones Bo had mentioned. They set their things upon them and shed their clothing like snakeskin. Merritt and Eric climbed in first, each of them squealing at the slimy floor, the heat of the water. Harper propped her phone, turned to video mode, in the V of a nearby branch and set it to record this experience for later uploading. Then she slipped into the hot springs next to Merritt, exactly next to her, their bare skin touching in places.

Audrey still hadn’t gotten in. She drank water, half a bottle. She heard, she thought, voices from off in the woods and wondered if it was their trailing camera crew not being quite quiet enough.

“Hey, will you play music? Something?” Eric asked her. “You’re the only one who still has dry hands.”

Audrey chose a playlist and turned up the volume. She sat on the mossy bank and dipped in her feet and legs up to her knees.

“You’re not getting in?” Harper asked like this was a personal affront.

“Eventually I will,” Audrey said. For now, she let herself fall back onto the moss, which was cool and plush. Her feet and ankles stayed in the warm water. She could hear the three of them talking softly about something but soon their voices were no different to her than the hum of the bugs. She closed her eyes to sleep.

And she did sleep. She thought she might have slept for hours, a deep dreamless sleep, like entering a cave and the entrance closing behind her.

She woke when there was a dripping shadow over her. It might have been the shadow from Spite Tower, a blocking of the sun, but it was only Eric trailing slimy algae from his swim trunks. He was holding her phone.

“Sorry,” he said. “We got tired of your playlist and I was finding something else.”

She tried to lick her lips, but it felt like moving two pieces of Styrofoam against each other. And she had blackberry seeds in her teeth. She could feel them now, back in her molars and along her gums. She needed water. She sat up, reached for a bottle, and caught Merritt and Harper kissing. Or maybe she didn’t catch them doing anything. They weren’t hiding it.

If Eric wasn’t here, she wondered, what then? Maybe nothing. Would she have wanted something?

Audrey unscrewed the cap, took a long drink of water, swished it around and around her mouth in an attempt to loosen those seeds and flush them out. Anyway, it didn’t matter, because Eric was most definitely here, standing above her while dripping and complaining.

She drank again. The water was warm now and unpleasant tasting. It seemed to coat her mouth without solving her thirst. But she could at least feel it dislodge some of the seeds. She stuck a finger in her mouth and dragged it along her gums until she’d collected them.

At first, when she looked down at her fingertip, she thought she’d pulled out a chunk of blackberry that had somehow escaped her chewing, a fleshy section of three still-plump drupelets. But right before she flicked it away, she saw what it really was: the tiny, severed head of a yellow jacket, its empty eyes staring back at her.

The moss beneath her seemed to undulate as she took it in, as she tried to make the head turn back to being a blackberry segment.

“The fuck’s up with your phone?” Eric asked. He sounded so far above her he might have been in a tree.

Audrey did not answer. She stared at the head, tried to make it unreal. She could feel other things still in her teeth, even more than before. She dragged her finger along her wet gum trench again, pulled it out. She thought she might vomit, could feel it bubble in her throat. The yellow jacket head was still stuck to her fingertip but now it was there along with other chewed pieces of its body.

“What’s wrong?” Harper asked, but she wasn’t speaking to Audrey, she was asking Eric about the phone.

“It’s really bizarre,” he said. “It’s—I think this is your feed.”

“What does that mean?” Harper asked. “Like my Insta?”

Eric looked back and forth, back and forth, between the screen on the phone in his hand and somewhere off in the trees.

“Eric, what?” Harper asked again.

“No, it’s like, I can’t even figure out how this could be happening,” he said. “What’s up with your phone, Audrey? What kind of witchcraft you got going here?”

Now Harper was climbing out of the water to join him. She too dripped over Audrey as she made her way to Eric.

Audrey could still feel things in her teeth, along her gums. She thought maybe if she took another drink of water, but as she tipped the bottle it caught the light and she saw that it had things floating in it. She looked closer: they were slimy threads of black algae.

“How is this even possible?” Harper was asking.

“I don’t know,” Eric said. “I tried to clear this screen to see if it’s an app, but it won’t let me close it.”

“Is it somehow picking up my phone’s signal?”

“How would that work?”

“Why are we playing around with our phones right now?” Merritt asked. She was still in the hot springs and had pushed over to the mossy bank. “Oh gross,” she said, noticing the bottle in Audrey’s hand. “What’s wrong with your water?”

Audrey looked down. Even in the mere moments since last she’d looked, scum had crept up the insides of the bottle and tinged the water yellow.

“What’s wrong with her phone is the question,” Eric said.

Merritt climbed out to see for herself and Audrey, legs shaky, also stood.

The buzz in the thicket had turned up and deepened. “Something’s wrong,” Audrey said. “I think something’s wrong with me.” Her voice sounded strange to her, almost as if rendered in the transatlantic accent she’d been scolded about that morning. But it didn’t matter because nobody else heard her. They were all so focused on the screen in Eric’s hand. Which now, finally, Audrey looked at, too.

It took her several seconds to understand what it was she was seeing.

“Jesus,” Harper said. “Fuck.”

Audrey looked off into the woods where Eric had been looking earlier. She saw Harper’s phone still propped on that branch, still recording, and then she understood while not understanding at all: her own phone screen was playing the live video feed that Harper’s phone was recording.

“How are you doing this?” Harper asked her.

“I’m not,” Audrey said. “I can’t imagine why it’s doing that.”

“Oh you can’t imagine?” Eric asked in a sneer.

“Why are you talking like that?” Merritt asked Audrey. “Are you mocking me?”

“No. I’m not, I—” Audrey looked at Merritt to explain but when she did, she noticed that Merritt had algae slime threaded through her eyebrow piercings and almost dripping down into her eye. She really thought she might vomit. “Merritt, you have—” she started to say.

But Eric yelled, “Oh fuck, look. Look!”

Audrey whirled to look behind them, bracing for the jump scare, but he meant at the phone screen.

“This is the tea, right?” Harper said. “This is the trumpets?”

Audrey turned back around, saw what they were seeing: there was something now on the opposite bank. It was hard to tell quite what it was because the angle of the camera placed it only in the top right portion of the screen, but it seemed to be folds of fabric, like the pleats of a long, black skirt. She looked up from the phone screen to the bank across the springs from them, where someone, presumably in a long skirt, should have been standing. There was no one there.

“It moved!” Eric shouted. “It just moved.”

“Wait, what are you seeing?” Merritt asked.

Eric held his finger on the screen, directly on the image, and as he did it grew larger and more complete. The woman, or the half of the woman they could see, now moved a step, then another, toward the water—and so more of her emerged within the frame. Her corset gave her black dress the much-desired wasp shape of the time. The whole look could have come straight from costumes and wardrobe. But still they could not see her head or face.

And still there was no one on the bank across from them.

“I’m not staying here for this,” Audrey said. “I’m going back.” The seeds in her teeth—they weren’t seeds, she knew that now—felt like they were twitching. The dense hum-buzz of the thicket was filling her head with black scribbles.

“I can’t understand this,” Merritt said. “This doesn’t—”

On the screen, the woman had started to bend toward the water, slowly, haltingly, and as she did—as her face came closer to an angle at which the camera, and they, would see it—the whole image began to cloud. Black algae crept from the corners of the screen and the image shuddered with it, almost like it was trying to shake it off.

The woman bent lower still, extended her hands toward the surface of the hot springs. They could see the top of her head now, her hair all pinned up, but her face was down, looking at the water. If she only looked up, they would see her—whatever face she might have, be it that of Mary MacLane, or inflamed from stings, puffy and bruised like a rotten apple. But the black spread of growth clouded the frame like smoke. Soon the image, the woman, would disappear in it.

Again, Audrey looked across the hot springs. But there was no one there. Except—in the thick growth beyond the bank: a movement, shuddering like a swarm. The seeds in her mouth came alive. Buzzing.

Audrey ran.

She left them looking at her phone and she ran through the Tricky Thicket as Clara Broward had once before her. It might have been her best performance yet, though even as she gave it, she wasn’t sure if it was a performance at all. Branches and brambles tore at her clothing. Her feet twisted in the undergrowth and slipped over patches of moss. She stumbled. She lurched. She ran on.

“Audrey, wait!” Merritt called after her. “Wait for me!”

But Audrey didn’t. She wanted to get free of the buzzing. Maybe Bo had hung speakers from the trees, because she couldn’t seem to leave it behind, not even once she’d cleared the thicket and was back in open woods. She wasn’t sure of the right direction, but she ran anyway. She could hear shouts behind her, but she did not slow for them.

Every few steps she’d spit, or try to, her mouth still so dry. But those seeds—they were not seeds!—were twitching in her teeth. She had to get them out. A squelch of mud shot up the back of her legs. A long branch scraped a line of skin from her arm. She did not stop.

Eventually, she could see their cottages growing larger through the trees. She ran to her own and in the door and to the kitchen sink, where she cupped water from the faucet and into her mouth and gargled and spit and did it again and again.

There, now swirling the drain, were legs and wings and a striped thorax, hopping in the sink like jumping beans. She spit out the stinger and her tongue went numb.

And she hadn’t left the buzzing. It had followed her in from the woods and filled the house with its constancy.

She felt weak, scooped out.

She gripped the edge of the counter and bent backward to lower herself to the ground before her legs gave out, but somehow the edge of the counter gave out first. A chunk of it, as light as packing peanuts, broke off in her hand and she tumbled onto the floor still holding it.

What she held, she saw, wasn’t wood at all. It was papier-mâché painted to look like butcher block, layers and layers shellacked together, and inside that: the hexagonal chambers of a yellow jacket nest.

Audrey looked up at the edge of the counter, where the piece had broken free, and saw more paper chambers inside. And now, she felt it—the thinnest flick of the air. A vibrancy. A hum.

And soon after she saw it, the searching head of a yellow jacket emerging from its chamber, twitching, looking at her. And now another right behind. And now another. They launched themselves into flight, chose a path over her shoulder, next to her ear.

She slumped back onto the floor.

From the front door of her tiny house, which she’d left open, she heard Merritt say, “Oh, Audrey. You really aren’t feeling well.”

And then her blurry vision gave up for black.