FOR THE PILGRIMS, A true church was a congregation formed when Christians covenanted with each other to walk in the ways of God. The covenant was, John Robinson taught, “the true essential property of the visible church.” The formation of a covenant was the reclamation of Christian liberty, the free act of the Lord’s free people. From it stemmed the “spiritual power, and liberty … to communicate, and partake in the visible promises, and ordinances.”1 Separatists also taught that true churches practiced proper government and discipline, and like other Reformed Protestants, they understood godly preaching and the biblical administration of the sacraments to be marks of true churches. By the standards of the Pilgrims, the Church of England remained a false church, an institution in which bishops tyrannized true Christians and denied them the liberty to worship God according to the dictates of the Bible.

At the same time, most other English Protestants would have regarded Plymouth’s congregation not as a church but as a lay conventicle. The colonists listened to sermons from a ruling elder—William Brewster—and other laymen. Because Robinson had remained behind in Leiden, the Pilgrims had no minister with them. No minister, no sacraments. New Plymouth’s children, such as Mayflower babies Oceanus Hopkins and Peregrine White, remained unbaptized. The colony’s men and women never celebrated the Lord’s Supper. Key components of ordinary church life, thus, were absent in Plymouth.

Even so, the nature of Plymouth’s church was not a flashpoint of controversy at first. Whatever their religious inclinations, the settlers focused on their survival, and there is no evidence that anyone took issue with the colony’s religious services. Moreover, even some settlers with no connection to the Leiden congregation expressed satisfaction with Plymouth’s church. For instance, William Hilton came to Plymouth in 1621 and wrote a glowing report of the colony’s prospects to a cousin in England. He was not a separatist, but he appreciated “the word of God taught us every Sabbath.” The fact that Brewster kept his sermons and prayers short by seventeenth-century standards probably endeared him to some settlers. “I know not anything a contented mind can here want,” Hilton maintained. In the long run, though, the irregular and stunted nature of Plymouth’s church was bound to cause problems.2

These problems arrived soon after the Wessagusset murders, when a string of English visitors and newcomers highlighted New Plymouth’s political fragility. Some newly arrived settlers, along with some of the Adventurers back in England, found it repugnant that Brownists governed the colony. A few settlers began worshipping according to the Book of Common Prayer. For the separatists among the Pilgrims, criticism from England and religious dissent at Plymouth were both alarming. They had left England to preserve their Christian liberty, and they worshipped according to their understanding of the Bible. The Pilgrim separatists knew that if other Englishmen wrested control of the colony away from them, they stood to lose that liberty.

In the spring of 1623, Thomas Weston sailed into Plymouth’s harbor. Once the Pilgrims’ benefactor, Weston was now a fugitive, on the run from his debts and from criminal charges. In a desperate bid to restore his finances, Weston had contracted to transport some cannons across the Atlantic, then turned around and sold them to an unknown buyer. According to Bradford, Weston made his way to New England, was forced to abandon his shallop during a storm, had his belongings and clothing stolen by Indians, borrowed some clothes in Piscataqua, and then showed up in Plymouth. Out of pity and gratitude for Weston’s past assistance, Bradford staked him with a hundred beaver skins.3

In September, Robert Gorges, son of Ferdinando Gorges, visited Plymouth. Over the past fifteen years, Ferdinando Gorges had financed a series of expeditions to New England. None had planted a colony or established a successful trade, but Gorges never fully abandoned his ambitions to make a fortune across the Atlantic. After establishing the Council for New England, Gorges sought new ways to promote colonies and commerce. For a while, the council planned to ask magistrates and judges to indenture pauper children and send them to New England, but the idea never gained traction.4

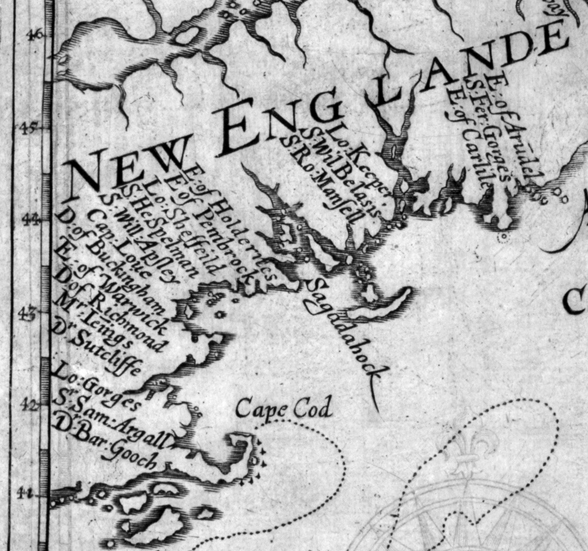

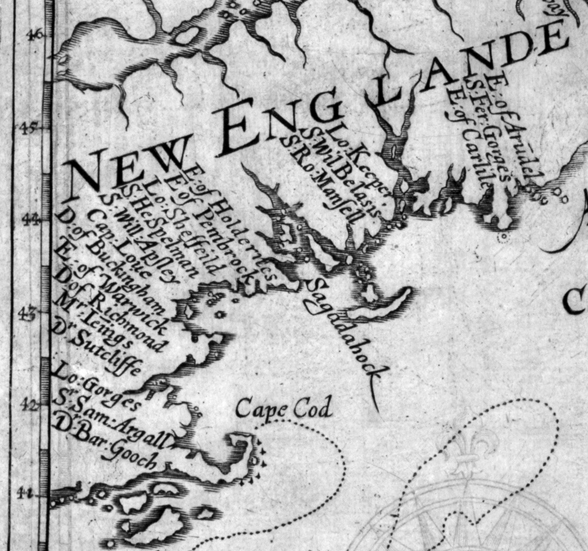

Gorges reckoned that investors would more readily fund colonies if they received allocations of land as their fiefdoms. He accordingly took a map of New England and divided it into some twenty portions. In June 1623, he invited prospective proprietors to Greenwich, where King James watched them draw lots for the portions. The king himself drew for several men who were absent. Sir Samuel Argall and Barnabe Gooch drew portions that together roughly comprised the subsequent boundaries of New Plymouth. Argall had spent the better part of a decade in Virginia; he is most remembered for his 1613 abduction of Pocahontas. Gooch was the longtime master of Cambridge’s Magdalene College; as of 1623 he also held a seat in Parliament. Neither man had any serious intention of setting foot on the New England lands assigned to them, but the council’s deliberations indicated New Plymouth’s insignificance and vulnerability.5

In the meantime, the council commissioned Robert Gorges as New England’s governor-general and asked him to establish a model plantation. Back in 1613, the younger Gorges had fatally stabbed a man in Exeter. Ferdinando Gorges obtained a pardon for his son, who then spent the next eight years as a mercenary soldier on the continent. When he returned to England, he worked alongside his father at Plymouth’s fort. None of these experiences had equipped Robert Gorges to plant a colony and govern New England.

The governor-general was also asked to apprehend Thomas Weston. After reaching Massachusetts Bay, Robert Gorges started up the coast to look for Weston, but a storm blew him off course. Gorges took shelter at Plymouth, and Weston had the misfortune to arrive for a visit at the same time. Bradford pled with Gorges to treat Weston with leniency. The indecisive Gorges arrested Weston, then changed his mind and released him. Weston made his way to Virginia, where he briefly held a seat in the House of Burgesses before moving on again, first to Maryland and then finally back to England, where he died in the mid-1640s.

Detail, from William Alexander, An Encouragement to Colonies (1624). The names on the map are those of the patentees of the Council for New England, reflecting the lots drawn at Greenwich in June 1623. (Courtesy of Library of Congress.)

When he came to New England, Robert Gorges brought several gentlemen, two Church of England ministers, and a number of families. Inauspiciously, they chose to settle at the site of the failed Wessagusset colony. The younger Gorges did not like the looks of his realm and sailed for home the next spring. Most of the colonists followed suit or went to Virginia, while a few scattered around Massachusetts Bay. Once more, Ferdinando Gorges’s ambitions had come to naught. It was much easier to draw lots and maps than it was to actually plant colonies.

When William Morrell, one of Robert Gorges’s ministers, visited Plymouth, he told its settlers that the Council for New England had granted him “power and authority of superintendency” over the region’s churches. Surely this raised some eyebrows among the Pilgrims. Morrell was not even a puritan, and the Pilgrims would never have accepted his superintendency. “It should seem he saw it was in vain,” Bradford commented. Morrell soon took passage for England.6

Much like Gorges and Morrell, some of the New Plymouth “Particulars”—those who had come to the colony at their own expense—decided that New England was not for them. They objected to the quality of the water, fish, and soil, and to the quantity of mosquitoes. On the latter point, Bradford commented that “they are too delicate and unfit to begin new plantations and colonies, that cannot endure the biting of a mosquito.” Such timorous souls should stay in England “till at least they be mosquito proof.” Bradford relished the fact that other would-be colonists fled from the same hardships the Pilgrims had overcome.

The Particulars also disliked Plymouth’s church, and when they reached England, they lodged complaints with the Adventurers. On behalf of the other investors, James Sherley forwarded their allegations to Bradford and demanded a quick response. At the top of the list was “diversity about religion.” Bradford denied that there had been any “controversy or opposition” pertaining to Plymouth’s church. The returned Particulars, though, expressed concern over the “want of both of the sacraments,” baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Bradford had a ready answer. “Our pastor is kept from us,” he reminded Sherley. Under the leadership of William Brewster, the settlers enjoyed prayers, psalm singing, and sermons, but no John Robinson, no sacraments.7

For the Pilgrim separatists, as for other Protestants, the sacraments were not a theological necessity. John Robinson drew a distinction between the “outward baptism by water, and an inward baptism by the spirit.” The two “ought not to be severed … yet many times are.” God would save his elect and bring them to faith, baptism or no baptism. Some English separatists had risked persecution by withholding their children from baptism in what they regarded as a false church.8

Still, like other Protestants, separatists insisted on the spiritual significance of something Jesus had commanded. “God hath made it [baptism] a most comfortable pledge and seal of his love and help to our faith,” taught Henry Barrow, the separatist martyr. Regardless of what their ministers taught, moreover, many English Protestants regarded baptism as a prerequisite for heaven. Until recently, the Church of England had permitted lay baptisms in the event an infant would die before a minister could perform the rite. Therefore, the inability to have their children baptized weighed on the minds of Plymouth Colony parents.9

The Leiden separatists had indicated the importance they placed on the Lord’s Supper by celebrating it each week. In this they were very unusual. Rural parishes in England celebrated Communion only the few required times each year. John Robinson never wrote a comprehensive statement of his understanding of the Lord’s Supper, but most separatists understood it as more than a mere symbol of Christ’s sacrifice. They did not believe that the bread and wine became the actual body and blood of Jesus Christ, but they understood the elements as—in Robinson’s explanation—“the communion of the body and blood of Christ, that is, effectual pledges of our conjunction, and incorporation with Christ, and one with another … all which eat of one bread, or one loaf, are one mystical body.” The Lord’s Supper furthered the unity of church members with Jesus Christ and with each other. The absence of the ritual each Sunday was a reminder that the ocean—and perhaps the Adventurers—had disrupted that unity.10

Given the importance of the sacraments, Elder Brewster in 1623 wrote Robinson to ask if he might baptize and preside over the Lord’s Supper until Robinson or another minister arrived. Robinson responded with a polite but firm no.11 Although the Pilgrims do not seem to have realized it at the time, Robinson’s presence (or his authorization of Brewster) would have caused more problems than his absence. Robinson and Brewster would have restricted the Lord’s Supper to church members and baptism to their children, and nonseparatists would have been deeply offended.

A few months later, the Pilgrims welcomed a minister, but not the one they wanted. In March 1624, the Charity reached the colony, carrying Edward Winslow back from his errand to England, and with him New Plymouth’s first cattle (one bull and three cows), a patent for a fishing outpost on Cape Ann, and some badly needed supplies and trading goods. The Charity also brought the Reverend John Lyford, accompanied by his wife, Sarah, and several children. “He knows he is no officer amongst you,” wrote Robert Cushman, “though perhaps custom and universality may make him forget himself.” Cushman and Winslow had told Lyford that he would have no ecclesiastical authority in Plymouth unless church members there elected him as their minister. Separatists insisted that ordinations at the hands of bishops were invalid. Only a particular congregation could ordain a minister, and a minister exercised spiritual authority only within that congregation. At the same time, Cushman and Winslow had consented to the Adventurers’ decision to send Lyford. If they could not have John Robinson, Plymouth’s church members should at least give Lyford a chance.12

Lyford was used to going where he wasn’t wanted. In 1613, the Oxford-educated minister had gone to Ireland. England’s nearest colony was a dumping ground for nonconformist puritans. English bishops were quite happy to send nettlesome ministers to Irish parishes, where they might convert a few individuals among the Catholic masses. Lyford went to Ulster, which King James had turned into an English plantation in 1609. After about a decade in the parish of Loughgall, Lyford accepted the Adventurers’ offer to go to an even less desirable place. Despite what he must have heard about the Pilgrims, Lyford presumed the settlers would be pleased to have him.13

Pilgrim leaders greeted Lyford with the respect due a learned minister. They gave him a generous allotment of food and invited him to give counsel on the colony’s affairs. Lyford quickly joined the church. “He made a large confession of his faith,” Bradford recounted, “and an acknowledgment of his former disorderly walking, and his being entangled with many corruptions, which had been a burden to his conscience.” In other words, Lyford regretted his prior ministry within an insufficiently reformed Church of England. He thanked God “for this opportunity of freedom and liberty to enjoy the ordinances of God in purity among his people.” In Lyford’s confession, the Pilgrims heard an articulation of the Christian liberty they cherished. Apparently, Lyford also told the church that he “held not himself a minister till he had a new calling.” Plymouth’s congregants were pleased with Lyford’s sentiments and invited him to preach.14

Despite the promising start, the Pilgrims concluded that Lyford was unfit to be their minister. According to Thomas Morton, who would soon come to New England and become the separatists’ bitter antagonist, Plymouth’s congregants demanded that Lyford “renounce his calling to the office of the ministry, received in England, as heretical and papistical.” Lyford would not go so far, halting at the line between puritan nonconformity and separatism. He maintained that the Church of England was “defective” but nevertheless a “true church.” Lyford’s stance was unacceptable to the Plymouth separatists. Their pilgrimage from England to Leiden to New England had begun with the decision to separate from a church they deemed beholden to Antichrist. At the same time, the Pilgrims’ demands were entirely unacceptable to Lyford, who quickly became disenchanted with the colony’s leadership.

Lyford had brought his family across the ocean and failed to obtain the single ministerial position in New England. Unsurprisingly, he resented the separatists who had rejected him. According to both Bradford and Thomas Morton, Lyford formed an attachment to John Oldham, one of the Particulars. Oldham was both disaffected and turbulent—Morton dubbed him a “mad Jack in his mood.” Bradford and other Pilgrim leaders learned that Lyford and Oldham were meeting with other malcontents. “It was observed,” Bradford chronicled, “that Lyford was long in writing,” drafting letters that would besmirch the Pilgrims’ reputations back in England.

Lyford wrote quickly because he intended to send his letters on the Charity’s return trip. When the ship anchored a few miles offshore prior to its departure for England, Bradford, Edward Winslow, and Isaac Allerton rendezvoused with the ship and visited with William Peirce, its captain. The Pilgrims had decided that they needed their own representatives in London to handle business with the Adventurers. Thus, Winslow was headed back across the ocean, this time accompanied by Allerton. Peirce, meanwhile, had been a friend of the Pilgrims since his first visit to the colony the year before.15

Bradford had not come to see Peirce for a friendly chat, however. The governor wanted the correspondence of Lyford and Oldham. Peirce gladly handed over more than twenty of Lyford’s letters, along with some written by Oldham. In the midst of their espionage, Bradford, Winslow, and Allerton discovered that their own correspondence was falling into the wrong hands. Within one of Lyford’s epistles they found copies of two letters, one addressed to William Brewster and one that Winslow himself had penned the previous winter while awaiting passage from Gravesend on the Thames. Evidently someone had filched them while Winslow was attending to other business. Lyford was sending the copies to a ministerial opponent of the Pilgrims back in England.

According to Bradford, Lyford had penned criticisms of the colony’s leaders “tending not only to their prejudice, but to their ruin and utter subversion.” In one of the letters, moreover, Bradford learned about a rather unusual conspiracy. “Mr. Oldham and Mr. Lyford,” Bradford wrote, “intended a reformation in church and commonwealth; and, as soon as the ship was gone, they intended to join together, and have the sacraments.” The rebellious settlers conspired to topple New Plymouth’s separatist government—not with guns, but with bread, wine, and water. The Pilgrim snoops made copies of the letters and kept a few originals to prove that Lyford had authored them. After Bradford obtained the letters, he did not tip his hand for several weeks. The governor wanted to see what Lyford and Oldham would do and who would support them.

Things soon came to a head. On the basis of his “episcopal calling [ordination in the Church of England],” Lyford began presiding over his own Sunday meetings, and there were settlers at Plymouth who very much wanted what he offered. William Hilton was among them. After coming to the colony in 1621, Hilton had expressed his satisfaction with Plymouth’s church. His wife and two children joined him two years later, and the couple had a third child the next year. When the separatists and Lyford failed to come to terms, the Hiltons asked the spurned minister to baptize their newborn son. As any Church of England minister would have done, Lyford obliged.16

Oldham caused different sorts of problems. According to Bradford’s account, when Myles Standish confronted Oldham about refusing guard duty, Mad Jack pulled a knife on the captain. The Pilgrims “clapped up [imprisoned]” Oldham. Thomas Morton told a similar story. Plymouth’s magistrates asked Oldham to come to the “watch house.” When he refused, they gave him a “cracked crown” and “made the blood run down about his ears.” Regardless of who had started the fight, Oldham ended up a prisoner.17

Bradford decided it was time for action and summoned Plymouth’s citizens to a court. He reminded them that they had come to “enjoy the liberty of their conscience and the free use of God’s ordinances” and that they had suffered greatly for those ends. By liberty of conscience, Bradford did not mean that individuals could pursue whatever religious convictions they happened to hold but that the separatist Pilgrims could worship God in ways that did not violate their consciences. Likewise, by the “free use of God’s ordinances,” Bradford did not mean that anyone should have access to the sacraments. Separatists objected to the “mixed multitude” of the Church of England, in which ungodly individuals sullied the Lord’s Supper. Bradford and other Pilgrim leaders contended that Lyford and Oldham threatened liberty, properly understood, by introducing corrupt forms of worship and by subverting the authority of Plymouth’s elected leaders. As far as Plymouth’s governor was concerned, it was a matter of sedition. If Oldham and Lyford had their way, the separatists would no longer govern New Plymouth.

Lyford protested his innocence, whereupon the governor produced the purloined letters and had them read aloud. The gathered settlers heard Lyford’s accusations, namely, that they “would have none to live here but themselves.” Lyford advised the Adventurers to keep the Leideners, especially John Robinson, away from Plymouth. Instead, the Adventurers should send enough nonseparatists “as might oversway them here.” Especially if the Particulars gained the right to vote and hold office, New Plymouth would cease to be a separatist colony. Lyford added that if given a choice, the settlers would eagerly select a replacement military leader, “for this Captain Standish looks like a silly boy, and is in utter contempt.” The oft-maligned Standish had to bear more insults about his stature.

The court convicted Lyford and Oldham—the exact charges are unclear—and banished them. Oldham left for Massachusetts Bay but returned the following spring and was arrested again. This time around, the Pilgrims dispatched him with more ceremony. The court “appointed a guard of musketeers which he was to pass through, and everyone was ordered to give him a thump on the brich [buttocks], with the butt end of his musket.” A boat then carried away Oldham’s sore bottom and bruised pride. Eventually, Mad Jack had something of a religious conversion, settled in Massachusetts Bay, and made his peace with Plymouth’s leaders.

For his part, Lyford made a public confession in church and begged for mercy. After the church’s deacon, Samuel Fuller, urged clemency, Plymouth gave him a reprieve from his expulsion, dangling the possibility of a pardon should his contrition prove genuine. It did not. In August 1624, Bradford again finagled one of the minister’s letters, addressed to the Adventurers. In it, Lyford criticized the nature of Plymouth’s church, which he claimed comprised “the smallest number in the colony.” He alleged that the separatists did not believe the church had any responsibility to those outside of its membership, who remained “destitute of the means of salvation.” For Lyford, a church encompassed everyone within the bounds of a parish. For the separatist Pilgrims, a church was a covenanted community of the godly.

Knowing that at least some of Lyford’s allegations had reached England, Bradford sent the Adventurers yet another defense of Plymouth’s church and government. He stated that instead of ignoring the unconverted, Plymouth enforced church attendance. The magistrates appointed several men to “visit suspected places” every Sunday. One surmises that given Bradford’s proven ability to locate incriminating letters, the Pilgrims easily tracked down Sabbath breakers. They punished those they found that were “idling and neglect[ing] the hearing of the word.” As to the lack of a minister, Bradford observed that their enemies kept their pastor from Plymouth and then unjustly reproached them for his absence. Still, they had Brewster. They preferred his lay leadership to what they considered Lyford’s false ordination.

Meanwhile, the Pilgrims carried out Lyford’s sentence of banishment. In the spring of 1625, the minister and his family followed Oldham to Nantasket on Massachusetts Bay, as did several other discontented Plymouth settlers. William Hilton and his family were among those who left. Several years later, the Virginia parish of Martin’s Hundred called Lyford as its minister. He moved parishes in Virginia at least once, then died in 1630 or shortly thereafter. Sarah Lyford, meanwhile, returned to New England with her children after her husband’s death. She settled in Massachusetts Bay and remarried.18

Lyford’s expulsion and death did not expiate Bradford’s wrath. When Plymouth’s governor composed this section of his history around two decades later, he wrote at great length about Lyford and included very unflattering information about the rejected and ejected minister. According to Bradford, Sarah Lyford exposed her husband’s past immoralities on the eve of their banishment. “She feared to fall into the Indians’ hands,” Bradford explained, “and to be defiled by them, as he [John Lyford] had defiled other women.” A long list of outrageous sins followed. Lyford had fathered a “bastard” prior to his marriage, denied it to Sarah during their courtship, and then brought the son into their home after their nuptials. Even worse, Sarah Lyford could not employ maids without her husband pressing himself upon them. The Pilgrims obtained corroboration of Lyford’s immoral behavior. In England, Edward Winslow found two witnesses with knowledge of his indiscretions in Ireland. They testified that the minister had arranged a private conference with a young woman prior to her marriage, then had raped her while taking care to “hinder conception.”19

Thomas Morton, who probably met Lyford after the latter’s banishment from Plymouth, suggests that the separatists had “blemish[ed]” Lyford’s character in order to portray him as a “spotted beast, and not to be allowed, where they ordained to have the Passover kept so zealously.” In other words, he lacked the separatist purity the Pilgrims demanded. Bradford’s accusations against Lyford, however, seem like more than just a smear. Scandal would explain Lyford’s departure from Ireland and his willingness to bring his family to a colony with which he had no prior connection. The minister probably had some spots.20

In his history of New England’s first sixty years of English settlement, Massachusetts Bay minister William Hubbard suggested that “the term of wickedness” with which the Plymouth separatists had branded Lyford and Oldham was “too harsh.” For Hubbard, the Lyford-Oldham controversy was a “small tempest” that “hazard[ed] the loss of a weak vessel.” For the separatists, however, it mattered precisely because their vessel—their colony—was so weak. Lyford and Oldham did exhibit “antipathy against the way of the separation,” but it was the combination of ecclesiastical dissent and political threat that produced the harsh reaction.21

The Pilgrims could have faced consequences for banishing a Church of England minister. Lyford and his supporters might have sought redress with the Council for New England, or with crown and ecclesiastical officials. It seems, however, that their complaints went no further than the Adventurers, and Winslow’s witnesses forestalled any serious repercussions. Bradford and Winslow had outfoxed their opponents and kept the colony’s political leadership in their own hands. “Thus was this matter ended,” stated Bradford.22

The matter was not ended, however. Coming on the heels of complaints from the Particulars, the fallout from the Lyford controversy prompted many of the Adventurers to withdraw their financial backing. As an investment, Plymouth had been an utter failure. Those who had ventured money had not received it back, let alone reaped profits. James Sherley informed Bradford that “want of money” was the paramount issue, but it was not just about money. Sherley did not mince words. Most of the Adventurers now loathed the Pilgrims, having read letters that denounced them as “Brownists, condemning all other churches, and persons but yourselves and those in your way.”23 The Pilgrims had pretended not to be separatists when they sought partners and patents for their emigration. Lyford had forced them to show their theological cards.

A few of the Adventurers still backed the Pilgrims. Sherley informed Bradford that the colonists and the remaining investors had £1,400 in debts, which the Pilgrims should settle by continuing to ship commodities to England. The price of beaver had risen in recent years, but the debt was imposing and hampered the colony’s prospects. In 1625, the Pilgrims loaded two ships with fish and furs. One ship dallied in English ports and did not reach the European market for dried fish until after a price collapse. Barbary pirates captured the second ship after it had already reached the English Channel, seizing its valuable cargo of beaver furs and enslaving its crew. “God’s judgments are unsearchable,” Bradford lamented.24

The year 1625 brought other heavy blows. Robert Cushman, who had never fully restored his friendship with the Pilgrims, died that spring. King James also died and was succeeded by his son Charles. An outbreak of the plague postponed the new king’s coronation and eventually killed seventy thousand of his subjects. “This year the great plague raged in all this kingdom,” wrote an official in Plymouth (England). The same outbreak killed one-fifth of Leiden’s population. The ten thousand dead included members of the English separatist congregation. John Robinson died after a brief illness, though apparently not from the plague. Far removed from the epidemics, Bradford reflected on the fact that his humble pastor and a great prince “left this world” within weeks of each other. “Death makes no difference,” he observed. It took the lofty and the lowly.25

The Leiden Pilgrims came to the New World to establish a haven and beacon for separatism, not a bastion of religious toleration and freedom. Their goal was to transplant a congregation, found a prosperous colony, and attract puritans wavering on the threshold of separatism to join them. Robinson’s death weighed heavy. The Pilgrims would not be reunited with their beloved pastor in this world, and only a small number of additional Leiden congregants emigrated after 1625.

Especially with most of the Leiden separatists remaining in the Dutch Republic, the Pilgrims were faced with questions to which they had given little thought prior to the Mayflower crossing. What would the relationship be between New Plymouth’s church and its government? How would that government deal with those settlers who kept themselves aloof from its separatist church or who wanted to worship according to their own consciences? By the mid-1620s, the Pilgrims had begun to answer such questions. The Pilgrims did not compel anyone to join their church, and the Mayflower Compact did not make civil distinctions on the basis of religious convictions or church membership. Church attendance, though, was compulsory, and the colony’s leaders banished those who began worshipping according to other principles.

Why, James Sherley wondered, were the Pilgrims “contentious, cruel and hard hearted … towards such as in all points both civil and religious, jump not with you?”26 Could they not have reached an accommodation with Lyford, or at least have permitted him to baptize the Hiltons’ son? In an important sense, however, there was nothing unusual about the way that the Pilgrims had acted. As of 1625, hardly anyone in old England or New England had abandoned the idea of religious uniformity. Most English Protestants, including conformist puritans such as Lyford, did not think that Brownists had the right to form their own churches within English parishes. Likewise, Plymouth’s leaders thwarted Lyford’s attempt to establish alternative worship services in the colony. The Pilgrims were determined to keep New Plymouth’s church and government in their own hands. They preserved their own liberty by denying it to others.