THE NUMBER OF QUAKERS and Baptists in New Plymouth grew significantly in the years after King Philip’s War, especially in the western portion of the colony. As was the case in England and in many other colonies, religious dissenters in Plymouth Colony were second-class citizens, grudgingly tolerated but subject to significant civil disadvantages. In the years after 1660, New Plymouth’s settlers were free to attend or ignore the established churches as they saw fit, and Quakers and Baptists usually could meet openly for their own religious services. In this respect, dissenters and the religiously indifferent enjoyed liberty of conscience.

As historian Alexandra Walsham explains, however, this degree of toleration “emphatically did not mean religious freedom” as that term would be understood in later centuries. The colony’s Congregational ministers and magistrates did not abandon the goal of religious uniformity or their antipathy toward alleged heresy. They understood the established churches as a public good, providing sacred functions for entire communities. The General Court required towns to levy taxes toward ministerial salaries and the construction and upkeep of meetinghouses. Dissenters received no exemptions from church taxes and suffered fines and imprisonment if they refused to pay. They also could not become freemen or, at least in many parts of the colony, participate in town affairs.1

In Scituate, there had been two churches ever since the early 1640s split over Charles Chauncy’s baptismal practices. Once Chauncy left for Harvard in 1654, nothing separated the two congregations except geography and lingering resentments. Especially after Nicholas Baker became minister of the north church in 1660, the town’s ecclesiastical relations gradually improved. With a heavy dose of condescension, Cotton Mather praised Baker’s “good natural parts,” which compensated for his merely “private education.” Baker had been a farmer and probably a lay preacher before his ordination. In Massachusetts Bay, councils of clergy assessed the learning and orthodoxy of ministerial candidates before ordaining them. Baker would not have become a minister in the Bay Colony. In New Plymouth, by contrast, laypeople ordained their ministers, and they sometimes elected men who lacked a university education. Baker and William Wetherell, still pastor of the south church, effected a reconciliation that was completed in April 1675. “We desire,” Baker declared that month, “God to forgive you and us whatsoever may have been displeasing to him.” The congregations did not reunite, but Scituate’s church members could now take the Lord’s Supper at either meetinghouse.2

In towns such as Scituate, Quakers faced less hostility for a stretch of years between 1660 and the start of the war. The most prominent Friend in Scituate was Edward Wanton. According to early nineteenth-century chronicler Caleb Hopkins Snow, Wanton had been one of the “officers under the gallows” at the time of Mary Dyer’s execution and “was so affected by the sight, that he became a convert.” Wanton prudently relocated to Scituate. He worked as a carpenter and shipbuilder and accumulated substantial property, including at least one African slave. Over Wanton’s forty-five years in Scituate, he hosted countless religious meetings at his home.3

When the Quaker missionary John Burnyeat toured New England in 1672, he spoke to a large crowd in Scituate that gathered in an orchard to hear him. According to Burnyeat, “some of the elders of their church” interrupted the meeting to dispute with him. Burnyeat maintained that New Plymouth’s 1657 banishment of Nicholas Upshall in the dead of winter had been cruel and “inconsistent with the gospel dispensation.” Ousamequin had acted more like a Christian than had William Bradford, Burnyeat charged. For their part, Scituate’s church leaders accused Burnyeat of heresy. Animosity remained, but New Plymouth leaders had abandoned severe forms of anti-Quaker persecution, and the Friends in turn backed away from their most aggressive forms of public witness. Quaker missionaries did not visit churches to rail against the colony’s ministers, and constables did not interfere with Quaker meetings.4

In Scituate and elsewhere, King Philip’s War stoked renewed tension between the Friends and other settlers. Congregational ministers preached that God was punishing New England because of its toleration of heresy and wickedness. The Quakers agreed that God was punishing New England, but they identified different sins as the cause. Magistrates and ministers had offended God by persecuting his Friends, and now God was taking vengeance. In March 1676, Edward Perry of Sandwich reported hearing a divine voice: “Blood for blood, and cruelty for cruelty.” Echoing the sentiments of other Friends, Perry lamented that a people who had gone “over the great ocean into this land … that they might have the liberty of their consciences to worship” now prevented others from exercising that same liberty. Perry maintained that New England’s afflictions would not end until the persecutors repented, but he promised that God would protect and deliver his faithful remnant—the Friends—from the carnage that surrounded them.5

Many Plymouth Colony Friends refused military service during the war. From the start of the movement, some Quakers had insisted that the Children of Light could not bear arms or in any way contribute to violence and warfare. After the restoration of the monarchy, pacifism increasingly became a movement-wide principle. In order to discourage persecution, Quakers leaders wanted to reassure King Charles II that they were not revolutionaries and posed no threat to his government. George Fox and other leading Friends declared in January 1661 that “all bloody principles, we … do utterly deny, with all outward wars and strife and fightings with outward weapons, for any end or under any pretense.” Jesus had commanded Peter to sheathe his sword, and Friends should follow the spirit of Christ. Prior to King Philip’s War, a few Quakers in Plymouth Colony were fined for their refusal to participate in militia training, but for the most part towns found ways to limit conflict over the issue.6

When the colony drafted men after the March 1676 raid on Rehoboth, the war council noted that “many of the soldiers that were pressed came not to go forth, especially Scituate and Sandwich proved very deficient.” Not all of these men were Quakers. Many men were loath to leave their families and farms; others simply wanted to avoid the horrors of war and possible death. Quakers in Sandwich, however, insisted that unlike others who only looked to their “own bodily interest,” their refusal was in obedience to “the command of Christ Jesus and a tender conscience towards God.” They were not at liberty to fight.7

Especially after the costly Native raid on Scituate in May 1676, townspeople resented the tender consciences in their midst. After the war, therefore, town leaders were less inclined to ignore Quaker violations of laws and communal expectations. In 1665, a town meeting had appointed men to rate—assess—each household to determine its portion of Scituate’s ministerial salaries. (Nicholas Baker and William Wetherell received £60 and £45 each year, respectively.) Constables then visited households to collect the tax. Quakers invariably refused to pay taxes to support churches and ministers they rejected as false. As in the case of militia service, prior to 1675 communities had avoided prolonged conflict over church taxes. Now the church rate provided an easy way to punish Quakers. In December 1676, for example, constables seized five pewter platters from Edward Wanton to satisfy his share of the rate. The next year, a constable took five yards of broadcloth.8

Another Scituate Friend, John Rance, refused both taxes and military service. Rance’s background is obscure. Sometime during the Massachusetts Bay governorship of Richard Bellingham (1665–72), Rance came to that colony from England as a Quaker missionary. He was imprisoned, and he moved to Scituate after his release. During King Philip’s War, Rance was among the town’s “delinquent soldiers.” In March 1676, the council fined him eight pounds. Later that year, constables seized some of Rance’s corn and sheep to satisfy his church taxes.9

In the summer of 1677, the constables returned. They demanded two shillings toward Nicholas Baker’s salary. Rance would not pay what he termed “the priest’s rate,” so the constables took a kettle from him. The outraged Rance followed them to the minister’s home and watched them give the kettle to Baker. The next Sunday, Rance marched into the north church meetinghouse. Alluding to the books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel, he denounced Baker as “no true minister but one of that sort of false prophets which the Lord sent his servants to cry woe against.” Rance cried woe, warning that God would punish false teachers who enriched themselves at the expense of God’s Friends. Baker was a wolf and a thief, Rance alleged.10

Magistrate James Cudworth called for the constable. Rance now had a second object for his scorn. “The Lord will meet with all hypocrites,” Rance told Cudworth. In the late 1650s, Cudworth had opposed the whipping and imprisonment of Quakers, and he had even hosted meetings of the Friends in his home. Cudworth wanted concord, not conflict, however. He had no patience with Rance, whom he ordered removed from the church. The next day, Rance was placed in the stocks. Cudworth then ordered Scituate’s constable to bring him to Plymouth, where Governor Josiah Winslow ordered his hat removed.11

In the meantime, Nicholas Baker sent a letter to the colony’s leaders. While Baker insisted that he was “far from a harsh rigid persecuting spirit,” he maintained that Quakers like Rance went too far. Rance and other Quakers openly spouted “damnable and blasphemous doc[trines],” peddled heretical books, and invited Scituate’s young people to their “diabolical worship.” Even worse, the Quakers had the temerity to meet near Baker’s church between its two services. As “nursing fathers to the churches of Christ,” the magistrates should not overlook the offenses committed against their children. They should punish John Rance, and two or three hours in the stocks would not suffice. The General Court agreed. New Plymouth’s magistrates and deputies convicted Rance of slandering Baker and Cudworth and of enticing young persons to hear “false teachers.” The penalty was twenty lashes. According to Rance, Governor Winslow commuted the sentence after ten blows.12

As Plymouth’s General Court punished John Rance, its leading citizens were contemplating new legislation designed to shore up the established churches. The previous month, the court had asked the colony’s ministers to help them define “those due bounds and limits which ought to be set to a toleration in matters of religion.” John Cotton canvassed his colleagues and drew up a list of essential doctrines. They proposed that “none be tolerated to set up any public worship” who did not accept the Bible as God’s word, the Trinity as defined in the ancient ecumenical confessions, and the justification of sinners as an act of grace irrespective of human merit. Moreover, the ministers rejected toleration for dissenters who accepted excommunicated persons into their communion, who disturbed approved worship services, or who denounced the established churches as “sinful and Antichristian.” (The latter point was ironic considering that the Pilgrim separatists, at least while in England and Leiden, had rejected the Church of England as Antichristian.) The statement was pointedly silent on the issue of baptism and thus did not target John Myles’s church in Swansea. Without mentioning them by name, the ministers made it clear that the Friends remained far outside the acceptable limits of toleration.13

A few days after John Rance’s whipping, the General Court passed additional legislation requiring towns to build meetinghouses and employ ministers. In particular, the court ordered that towns collect a single rate that would include the minister’s salary with the community’s other expenses. The court also threatened to take charge of local taxation should towns fail to meet these obligations. Some ministers were upset that the court did not adopt harsher measures. Why had the General Court asked about the proper limits of toleration if it intended to tolerate heresy anyway? “It makes my loins at a stand,” fumed Taunton’s George Shove. “I never was more disappointed.” The new laws did not interfere with Quaker meetings or proselytizing.14

Shove was disappointed, but so were the Friends. In communities such as Scituate, constables seized cows, sheep, cloth, corn, barley, sugar, kettles, cups, platters, and porringers. In June 1678, Edward Wanton and several other Quakers petitioned the General Court. “Christ Jesus invites people freely,” they maintained. “His ministers ought not to make people pay.” Ministerial rates smacked of Jewish tithes and Catholic tyranny. Wanton and his fellow petitioners minced no words in their rejection of New Plymouth’s churches. “We do really believe your preachers are none of the true ministers of Christ,” they informed the magistrates. They also reminded their persecutors that they enjoyed their own “liberty but upon sufferance” of a king who found New England’s Congregational churches “repugnant.”15

The court ignored the petition, but it made its displeasure known by fining Wanton ten pounds for a “disorderly” marriage. Plymouth law required the public announcement of betrothals and permitted only magistrates or persons authorized by them to join couples in marriage. (Plymouth Colony ministers did not perform marriages.) Quakers contravened the law when they married privately in their own ceremonies. Wanton would not pay the fine, so a constable seized two oxen and a cow from him to satisfy it. When Wanton refused to contribute his assigned portion to Scituate’s meetinghouses, town leaders jailed him for six weeks.16

Arthur Howland Jr.—nephew of Mayflower passenger John Howland—also ran afoul of the more stringent enforcement of church taxes. The family had a long tradition of civil disobedience and resistance to authority. Howland’s father had broken with Marshfield’s church in the 1650s, hosted Quaker meetings, become convinced, and allegedly threatened to kill the town constable who tried to arrest him. In March 1667, the General Court fined the younger Arthur Howland five pounds “for inveigling of Mistress Elizabeth Prence and making motion of marriage to her, and prosecuting the same contrary to her parents’ liking.” Elizabeth Prence was the daughter of then governor Thomas Prence, who probably opposed the match because of the Howland family’s involvement with the Friends. Howland trudged back to Plymouth a few months later and promised the court to “wholly desist” from his efforts to marry Elizabeth. He promptly broke his promise; the couple married that December. Prence apparently forgave his daughter for her disobedience. When Prence died, Elizabeth Howland inherited a share of his considerable estate equal to that of her six sisters. The governor also left her a silver saltcellar and a black cow.17

Arthur Howland Jr. was not a Friend at the time of his marriage, but a decade later he became convinced. Samuel Arnold, Marshfield’s minister, ordered Howland to come before the church to answer congregational charges against him. Howland agreed to appear if he could have “liberty to read” a statement he had written explaining his new principles. Arnold would not grant that liberty, so Howland refused to come, stating that Arnold would require him “to put off my hat and stand before the church.” The Marshfield church then excommunicated Howland in absentia. Arnold warned the congregants that “they should not eat or drink with” Howland, and church leaders even cautioned Elizabeth Howland against eating with her excommunicated husband.18

While they continued sharing meals, the Howlands soon had less to eat. Excommunication did not absolve Arthur Howland of his civic responsibility toward Marshfield’s church. In the summer of 1682, the town tasked Richard French with collecting the town-mandated rate for Arnold’s salary. Arnold received fifty pounds a year, half paid in either corn or cattle, and the other half paid in wheat, barley, pork, butter, or silver money. The arrangement was typical. Inhabitants of Plymouth Colony had little hard money, so governments permitted payments in kind. Given his wife’s inheritance, Arthur Howland could have afforded to pay the fifteen shillings that Marshfield expected him to contribute. Howland, however, was not about to pay a penny. French responded by seizing property. According to Howland, French “took away our butter scarce leaving us a convenient dish or basin to eat our vittles in.”19

Two years later, French was back. This time, he took Howland himself and brought him to Plymouth. According to Howland, he was jailed without a hearing before a court or magistrate. He was “not allowed neither bread nor water, nor anything to lie on but the floor, nor anything to cover me with, nor liberty to go … to get anything for my money.” If his case resembled that of other Friends, Howland probably languished in jail for about a month.20

Some non-Quakers also opposed the General Court’s heavy-handed oversight of the colony’s churches. In Scituate, it was burdensome and complicated to maintain two buildings and two ministers. By the late 1670s, Nicholas Baker had died, William Wetherell was infirm, and the south church’s meetinghouse had fallen into disrepair. Now that the two churches were no longer at odds, townspeople discussed the possibility of reuniting the two congregations. The south church sought advice from neighboring ministers, who recommended that the town maintain both churches and that the south church raise a new building and obtain an assistant for Wetherell. The town ignored the expensive advice and voted to “reduce the whole inhabitants into one congregation.” Why should Scituate’s taxpayers support two churches no longer separated by the old dispute over baptism?21

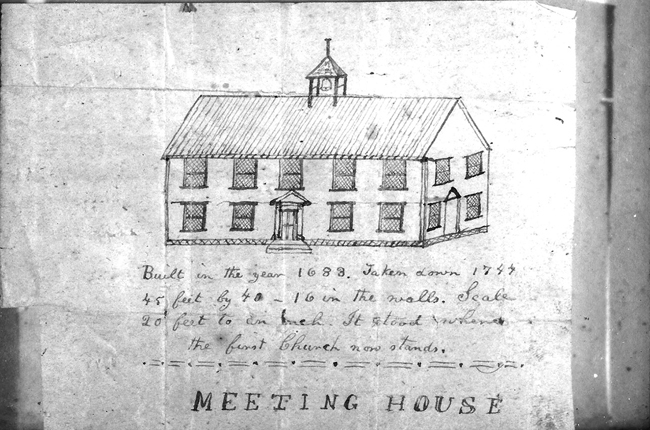

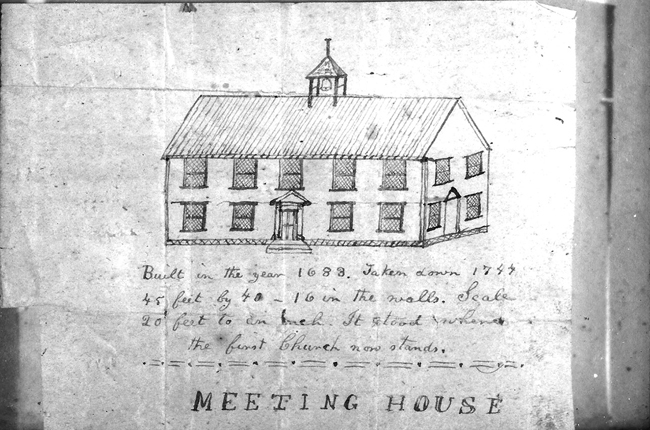

Sketch of Plymouth’s 1683 meetinghouse. (Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts.)

The General Court then invalidated the town vote and appointed a committee of three ministers and three magistrates to oversee the construction of a new meetinghouse for the south church. In a June 1680 petition, twenty Scituate men argued that the General Court’s action was “contrary to the due liberties of our town.” Why should the colony’s magistrates tell them what to do about their meetinghouses? If townspeople wanted a single church, surely that was their prerogative. Although they did not belong to either church, the petitioners professed themselves willing to contribute “in a regular way for the maintaining the worship of God without any such forcible means.” Recently, however, the General Court had assumed control of the collection of Scituate’s church taxes. The twenty men asked why the court treated them “as children under age.” In other words, they were taxed without their consent or representation. Despite the objections, Scituate’s south church built its new meetinghouse in 1681.22

The situation in Sandwich was very different from that in Marshfield or Scituate. Following the departure of William Leverich in the mid-1650s, Sandwich lacked a regular minister for nearly two decades. The town also ignored the law that long-standing male inhabitants take the oath of fidelity, and more than a dozen Friends voted in town affairs and retained their right to future divisions of town land. The Quaker Edward Perry held a number of offices in the 1660s and 1670s; he was one of several men who set the tax rates for Sandwich’s contribution to the colony’s wartime expenditures.23

In 1678, Sandwich church members asked the General Court to put an end to this permissiveness. The petitioners alleged that their Quaker neighbors impoverished newly recruited minister John Smith and neglected the glaring need for a new meetinghouse. Apparently, the building was so dilapidated and cramped that some individuals had to stand or lie down outside during services. (Given the long-standing apathy in Sandwich toward the established church, it is hard to imagine that the meetinghouse could not contain the town’s worshippers.) Church members in Sandwich could not redress the situation because the Friends and those sympathetic to them “over voted” them at town meetings. “That such persons should have liberty by voting” offended God, the petitioners warned. They begged the General Court to take action. The colony’s freemen complied with the request and ordered the town to administer the oath, which Quakers refused to swear. Many of the Friends then lost the right to vote and to participate in future divisions of town property.24

Sandwich Friends repeatedly petitioned the General Court to restore their civic privileges. In 1681, four Quakers—William Newland, William and Ralph Allen, and Edward Perry—complained that they remained in “many ways deprived of that just and free liberty which by the law of our native land we are born heirs unto.” The Sandwich petitioners denied any interest in “licentious practices” or “pretended liberty.” They only wanted “the liberty that is pure and peaceable,” a spiritual liberty that purified individuals from sin and a political liberty that allowed them to enjoy their “natural privileges.” They noted that other New England jurisdictions—Rhode Island—permitted Friends to “engage” their loyalty to the king, absolving them of the need to swear an oath. Sandwich’s Friends asked for a similar accommodation and an end to the measures that made them a political underclass.

A threat followed. If Plymouth’s magistrates and freemen rebuffed their request, they would appeal to the king. As Edward Wanton and his fellow petitioners had done in 1678, the Sandwich Friends reminded Plymouth’s leaders that their own freedoms were fragile. “The liberty you enjoy,” they wrote, “is but by license and leave” from the English king. The magistrates would be more likely to keep their liberty if they extended it to others.25

The threat was not idle. The colony’s authority to govern itself hung in the balance for fifteen years following the end of King Philip’s War. Prior to this time, English officials and monarchs had paid only occasional attention to their North American colonies. In the mid-1630s, Charles I had consented to New England’s reorganization under a single governor-general, but the plan lost traction with Thomas Gorges’s failure and the onset of the Civil War. During the Interregnum, Parliament passed the first of a series of Navigation Acts that regulated colonial shipping and trade, and the crown seized New Netherland soon after the Restoration. Only in the mid-1670s, however, did royal officials develop a more sustained interest in their North American colonies, an interest that came about in part because of England’s transatlantic rivalry with France and in part because of the wars and rebellions that wracked New England and Virginia. Charles II and his officials concluded that if they wanted to keep their empire, they would have to govern and defend it.26

As a sign of England’s newfound imperial consciousness, the Privy Council’s Committee on Trade and Foreign Plantations (known as the Lords of Trade) dispatched Edward Randolph to Massachusetts Bay in 1676. Approximately forty-five years of age, the Canterbury-born Randolph had held several minor positions, first with the Cinque Ports and then with the navy. Randolph’s financial compensation did not match his aspirations, and he was now looking across the Atlantic to find more lucrative opportunities. For the next fifteen years, Randolph played a significant role in mediating royal policy toward the New England colonies.

Randolph’s immediate task was to deliver a letter about his cousin by marriage Robert Mason’s proprietary claims to New Hampshire, but he also prepared detailed reports on the colonies he visited. Randolph informed English officials that the Bay Colony was a den of antimonarchical and duplicitous politicians, seditious ministers, and brazen smugglers. He blamed Massachusetts settlers and politicians for the wars against Natives across New England, accurately charged that colonists sheltered some of the regicides responsible for King Charles I’s execution, and alleged—also accurately—that Boston merchants ignored the duties and requirements of the Navigation Acts. Over the next decade, Randolph repeatedly urged English officials to consolidate New England into a smaller number of colonies with royally appointed governors. While some Massachusetts settlers favored warmer relations with the crown and welcomed royal assistance against the Indians and the French, most of the Bay Colony’s ministers and elected leaders regarded the combative Randolph and his proposals with intense suspicion and disdain.27

Given the enmity he faced in Massachusetts and his allegations against Bay Colony leaders, Randolph sought allies elsewhere. In July, he went to Plymouth at Governor Josiah Winslow’s invitation. Randolph did not stay long enough to gain a deep understanding of the colony. For instance, he observed inaccurately that in New Plymouth there were “no slaves, only hired servants.” Randolph praised New Plymouth’s governor as a “stout commander” who was “eminently popular and beloved in all the colonies.” Winslow was a loyal royal subject, a counterweight to the seditious Bostonians. According to Randolph, Winslow chafed against the Bay Colony’s “encroaching upon the rights, trades, and possessions of the neighboring colonies” and believed “that New England could never be secure, flourish, nor be serviceable” until “reduced” to royal government. Randolph sailed for England in the fall of 1676 convinced of the Bay Colony’s disloyalty and of Winslow’s goodwill. It is unlikely that Winslow felt any genuine desire for royal government. His obsequiousness stemmed from a recognition of New Plymouth’s weakness, and he was willing to advance his own colony’s interests at the expense of Massachusetts.28

Winslow’s approach paid dividends. Even though New Plymouth did not send an agent of its own to England, and despite the fact that its gifts and letters sometimes failed to reach their intended recipients, Charles confirmed New Plymouth’s jurisdiction over Mount Hope, Sakonnet, and Pocasset, and the king suggested that he soon would give the colony its charter. Randolph’s advocacy is the most reasonable explanation for this success.

New Plymouth’s prospects had never been so bright. In a 1680 report to the Privy Council, Winslow estimated that the colony’s settlers included twelve hundred men between the ages of sixteen and sixty, and he counted eight hundred births in the past seven years. Settlers, from other colonies and from Plymouth’s own towns, were moving onto the newly conquered lands. Massachusetts Bay buffered New Plymouth from the threat of Abenaki raids or French incursions. Although many inhabitants still eked out a living on land of dubious fertility, the colony was stable and secure and enjoying the favor of English officials.29

Randolph returned to Boston in 1679 as the royal customs agent for New England. The new position made him even less popular in Massachusetts Bay. Two months later, Randolph confided to Winslow that if the crown consolidated the New England colonies, he hoped it would attach the southern portion of Massachusetts Bay to New Plymouth and appoint Winslow as governor. Winslow would obtain a significant salary increase with the preferment. Perhaps it was a stretch to think that the king would grant such an honor to the son of a man—Edward Winslow—who had accepted appointments from Oliver Cromwell. Nevertheless, Randolph asked Winslow to travel to England in his company and present the case to the Lords of Trade. For his part, Winslow praised Randolph in letters to English officials as “faithful and careful in what he is betrusted” and lamented that he endures “many unkindnesses and disappointments in our neighbor colony.” In July 1680, Plymouth’s General Court honored Randolph by making him a freeman of the colony.30

Winslow, though, declined the trip to England, citing ill health and a fear of Turkish pirates. By the fall, the colony’s leaders had decided not to send anyone at all and instead to rely on the services of William Blathwayt, an ambitious young Privy Council clerk and secretary to the Lords of Trade. Winslow understood that obtaining a charter would require what amounted to bribes, so he made arrangements to pay Blathwayt for his services. Had Blathwayt wished to advance New Plymouth’s interests, he probably could have done so. Over the next decade, Blathwayt acquired a rich wife, numerous offices (including secretary at war), and the confidence of three very different kings. While he was happy to take some of Plymouth’s money, Blathwayt concentrated on advancing himself rather than a tiny, remote Congregational colony.31

Winslow further disrupted Randolph’s plans by dying in December 1680 at the age of fifty-two. His end was painful. He suffered from “gout and griping [bowel spasms],” Boston’s Samuel Sewall reported, and the “flesh was opened to the bone on his legs before he died.” Like his Pilgrim father, Josiah Winslow was savvy, energetic, and widely traveled. His parentage, wealth, and bearing had commanded respect from his fellow New England magistrates and made a positive impression on Edward Randolph. For New Plymouth, Winslow’s death was a heavy blow. Deputy Governor Thomas Hinckley praised him as a “noble, gallant, and accomplished gentleman.” The General Court allocated forty pounds toward Winslow’s funeral expenses.32

Longtime colony secretary Nathaniel Morton wrote letters to Penelope Winslow to express his condolences and provide her with some theological comfort. Morton closed one of his letters with a quotation from John Robinson’s popular Observations Divine and Moral. “We are not to mourn for the death of our Christian friends,” Robinson taught, “as they which are without hope.” There was no reason to mourn on behalf of the deceased, as God would raise them to a more glorious life. Nor should bereaved Christians feel abandoned by God. “But we should take occasion by their deaths,” instructed the Pilgrim pastor, “to love this world the less, out of which they are taken, and heaven the more, whither they are gone before us, and where we shall ever enjoy them.”33

The next June, Plymouth’s freemen chose Hinckley as Winslow’s successor. Born around 1620 in a Kentish village, Hinckley moved with his parents and siblings to Scituate and then to Barnstable. The family had been members of John Lothrop’s church in London, and Thomas Hinckley remained—according to Edward Randolph—a “rigid Independent [Congregationalist].” Edward Cranfield, the crown-appointed governor of New Hampshire, informed the Lords of Trade that Hinckley and his assistant Barnabas Lothrop were “weak men and very unfit to be concerned in government.” Cranfield was a vigorous defender of royal prerogative in New England, and he loathed nearly all of the region’s magistrates and ministers. At least some of those ministers, however, agreed with Cranfield’s assessment of Hinckley. Cotton Mather jabbed that in New Plymouth, a “nullus”—a nobody—had succeeded Winslow’s lion. Hinckley proved entirely incapable of shepherding his colony through the political tumults of the next decade. Whereas Winslow could build ties with men such as Randolph, Hinckley antagonized English officials and eventually alienated many of his own colony’s settlers as well.34

New Plymouth had not had an effective and loyal agent working on its behalf in England since Edward Winslow had represented the colony. Finally, in the summer of 1681, Hinckley asked James Cudworth—recently elected as deputy governor—to sail to England. More than any other magistrate, Cudworth might have alleviated royal concerns about the colony’s religious establishment and its treatment of Quakers. Cudworth, however, was nearly seventy years of age, and he died of smallpox soon after he reached London. His modest estate included “one Indian boy,” worth—along with a “case” and some “bottles”—six pounds. In 1683, the magistrates asked Ichabod Wiswall, Duxbury’s minister, to replace Cudworth. Led by octogenarian John Alden, the former Mayflower cooper, Duxbury’s householders—church members and others—voted against releasing Wiswall for the assignment. Plymouth thus left its interests in the hands of William Blathwayt, to whom Hinckley sent fifty guineas in March 1683.35

While Blathwayt promised New Plymouth “a pre-eminence before others, whose behavior has been less dutiful,” both he and Randolph soon became less encouraging. One issue was the colony’s ongoing persecution of Quakers. Winslow explained in a 1680 report to the Privy Council that New Plymouth gave “equal respect and encouragement” to all Protestants “except the Quakers, and them we disturb not if they do not disturb our peace.” Winslow and Hinckley did not feel any need to hide their distaste for Quakers, probably because their colony’s treatment of the Friends was not harsh by English standards. While some English communities no longer persecuted Quakers, officials elsewhere seized their property, and some Friends fell victim to mobs as well. During episodic crackdowns on religious dissenters, English authorities imprisoned hundreds of Quakers. Scores died in prison. The king, however, expected Quakers in his colonies to have more liberty than those in England. Hinckley reassured Blathwayt in 1683 that “since we had any hints of his majesty’s indulgence to them,” New Plymouth had treated the Friends with more forbearance. The governor noted that the colony fined Quakers for disorderly marriages, but he offered to tolerate such marriages if the king so desired.36

Randolph also criticized Hinckley for countenancing “the late arbitrary, and till now unheard-of, proceedings” against the merchant John Saffin, who had purchased land on Mount Hope (Bristol) but continued to live in Boston. In 1682, Bristol’s constable, Increase Robinson, sought to collect Saffin’s portion of the town rate, which included money toward a house for the town’s first minister. Saffin refused to pay and refused to let Robinson take any of his property. Hinckley ordered Saffin kept in Plymouth’s jail until he paid the rate and fees related to his arrest and confinement.37

Randolph and Blathwayt decided that their earlier assessments were wrong. Plymouth Colony’s government and church establishment resembled those of Massachusetts Bay. And unlike the Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony did not have a charter. “All you can pretend to by your grant from the Earl of Warwick [the 1630 patent] is only the soil in your colony,” Randolph leveled with Hinckley, “and no color for government.” Blathwayt informed Plymouth that its charter would have to wait until the crown resolved what to do about the Bay Colony. “From hence it will be that your patent will receive its model,” he told Hinckley.38

The king and his officials decided to bring Massachusetts Bay to heel. The Lords of Trade obtained a quo warranto, which ordered the Bay Colony to defend its actions—and, by extension, its charter—in court. At the same time, Charles promised the recalcitrant Bostonians that if they resigned their charter, he would make minimal changes to it and their form of government. If they refused to cooperate, they would lose their charter anyway, and more sweeping changes would be made. Massachusetts leaders preferred to be bent rather than to bend. In November 1684, the Court of Chancery invalidated the Massachusetts Bay charter. Plymouth’s northern neighbors now had no legal basis for their government. That same month, the Lords of Trade recommended that New Plymouth be joined to Massachusetts. The Pilgrim colony’s loss of self-government seemed assured.39

By this point, Plymouth’s governor understood the possible results of royal control. In New Hampshire, crown-appointed governor Edward Cranfield jailed minister Joshua Moodey when the latter refused to celebrate the Lord’s Supper according to the Book of Common Prayer. “The good Lord prepare poor New England for the bitter cup,” Moodey wrote Hinckley.40