CHAPTER 24

POVERTY

“American children, the poorest in the developed world.”1

Le Figaro,

November 3, 2009

“The United States also has the highest proportion of workers in poorly paid jobs, and the highest number of annual hours worked by poor families with children…. Our poverty rates are higher for two reasons: because our jobs pay low wages and because, even with high levels of low-wage work, US antipoverty policy does less to compensate low-wage workers than do other nations.”2

TIMOTHY SMEEDING,

University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2008

In a Presidential election campaign that touched on so many aspects of American life, the modest discussion about poverty in 2012 reflected diminished concern for the least advantaged Americans. That is a stark contrast with voters in the family capitalism countries, who have proven willing to support programs that limit poverty, provide livable wages for the working poor, and secure a decent retirement for all. These disparate attitudes toward the least advantaged reflect better opportunity under stakeholder capitalism and expectation by voters of real wage gains continuing in perpetuity. Those expectations engender a spirit of community and optimism, undercut in America during the Reagan decline.

Recall that the late philosopher John Rawls believed the measure of a society is how well it deals with the less able. His gold standard for evaluating the variants of capitalism is how well families prospered while also enabling meaningful economic participation by the disadvantaged including the working poor, single parents, and high school dropouts. How do the family capitalism countries compare with Reagan-era America in meeting the Rawls standard?

Attenuating Poverty

With 20 percent of American adults considered to be working poor in near-poverty-income jobs or worse, according to MIT’s Osterman, the closest thing to a magic bullet to attenuate US poverty is higher wages, especially higher minimum wages. Other steps include access to a quality public education for all families and more expansive upskilling by the public and private sectors. Yet Reagan-era policies have pursued the opposite course in each instance. Unsurprisingly, poverty has worsened.* Here is how the Brookings Institution’s Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill describe events in 2009:

“The lack of progress in combating poverty is especially surprising…. Economic growth should have automatically reduced the portion of people falling below (poverty) thresholds. The primary reasons for this lack of progress are the stagnation of wages at the bottom of the skill ladder and changes in family composition…. Men in their thirties have lower wages than their fathers’ generation did at the same age.”3

American poverty is measured utilizing a system devised in the 1960s by an innovative and justly famous Social Security Administration economist, the late Molly Orshansky. It relies on costs of various baskets of goods and services considered to be necessities for lower-income households. Much has changed in the past half-century. Her approach has been criticized from both the left and right, and by Orshansky herself. The Census Bureau now publishes a variety of alternative measures, yet that concept remains the fundamental matrix of American poverty. Nearly one in six Americans, or more than 45 million adults and children, are meeting the Orshansky official threshold for impoverishment in 2013.

Even so, poverty is understated. Critics at the National Academy of Sciences, among others, have determined that the Orshansky concept undercounts poverty by as much as 20 percent in high-cost areas such as New York City.4 Moreover, because it excludes common expenses such as health care and some sources of income, Orshansky is not utilized by any other nation. The EU countries, for example, rely on continent-wide standards established in 2001 at Laeken, in the Netherlands. We can compare the extent of poverty in the United States and northern Europe using both measures, thanks to a 2007 analysis by researchers at Maastricht University in collaboration with Harvard and the University of Michigan. The results are reproduced as Table 7.

Poverty Rates in America and Northern Europe

Population Share Below Poverty Standards, 2000

Measured by European Laeken Standard |

Measured by U.S. Orshansky Standard |

|

| Poverty Rate: | ||

Austria |

11.9% |

4.8% |

Belgium |

13.3% |

3.6% |

Denmark |

10.8% |

3.4% |

France |

15.4% |

6.5% |

Germany |

11.1% |

5.1% |

Netherlands |

11.3% |

6.6% |

Sweden |

10.4% |

5.7% |

United States |

23.5% |

8.7% |

Table 7.

Source: Geranda Notten and Chris de Neubourg, “Poverty in Europe and the USA: Exchanging Official Measurement Methods,” Table 2, Graduate School of Commerce, Maastricht University, August 2007.

The northern European amalgam of widely broadcasted wage gains, higher minimum wages, numerous high-value jobs, and expansive safety nets translates to considerable less poverty than in America when measured with uniform statistics. The northern European Lacken standard is the more demanding one, requiring a higher income to avoid official penury. For example, the American poverty rate of 8.7 percent in 2000 would have measured 23.5 percent on the Laeken standard; nearly one in four Americans that year, or about 70 million, lived in poverty by European standards. In contrast, poverty in northern Europe would be nearly defined away by the less-demanding Orshansky standard.

Measured by either standard, the incidence of poverty in America is about twice as severe as in northern Europe. And if differences in the out-of-pocket cost of health care, pensions, and education required for membership in the middle class were included in these measures, the difference in poverty rates would be even greater. Here is how the authors Notten and de Neubourg put it:

“Generally speaking, the out-of-pocket costs of post-secondary education for a family with children are considerably lower in continental Europe than in the United States. To provide children similar education opportunities, US families thus need a higher income than continental European families. Ideally, such differences should be taken into account.”5

Chronic Poverty Is Twice as High in America as Northern Europe

Is chronic poverty more widespread in the United States? We learned earlier that the decline in American opportunity since 1980 is especially evident for lower-income Americans, too many trapped in a multigenerational poverty cycle. This cycle is an especially telling matrix for the performance of Reagan-era America. Lacking good incomes or social capital, families suffering chronic impoverishment have difficulty effectively empowering their children for a life of achievement, mobility, and accomplishment. Their children have a diminishingly small opportunity to break free of their economic class, perpetuating the poverty cycle.

Notten and de Neubourg captured these families in their analysis by defining long-term or chronic poverty as those who had lived impoverished during two of the previous three years. Like overall poverty, the Maastricht study revealed that the incidence of chronic poverty in northern Europe was generally less than half that in America; uniformly applying the Laeken standard, chronic poverty ranged down from 8.7 percent in France to 6.1 percent in Germany to 5.2 percent in Denmark, compared to 13.8 percent in the United States during their study year 2000.

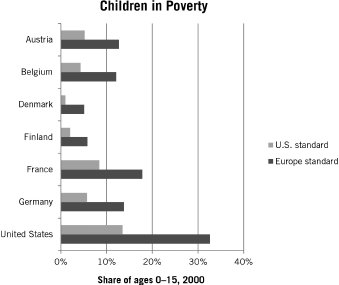

American Childhood Poverty Is Double the Rate in Northern Europe

The Reagan decline has been destructive to American families and in particular children. Low opportunity has weakened households, stagnant or falling wages raising havoc with its structure and impoverishing a greater share of US children than in northern Europe.

How severe is childhood poverty in America?

There are two comprehensive analyses that have recently answered that question:

First, a 2010 analysis of childhood poverty among the global 24 richest OECD nations by UNICEF ranked the United States twenty-third, stuck at the bottom between Hungary and Slovakia.6

Second, Notten and de Neubourg of Maastricht University examined the incidence of childhood poverty, using both the Laeken and Orshansky standards. Their results are reproduced as Chart 24.1. A stunning one in every three American children lived in poverty in 2000, when measured by the Laeken standard. That rate was twice the childhood poverty rate of any nation in northern Europe. Moreover, because of income churning by lower-income households, the actual reach of childhood poverty in the United States is underestimated by Notten and de Neubourg. A remarkable one-half of all American youths during childhood are destined to experience bouts of poverty, reliant at some period on food stamps, a startling statistic.

Chart 24.1.

Source: Geranda Notten and Chris de Neubourg, “Poverty in Europe and the USA: Exchanging Official Measurement Methods,” table 7, Graduate School of Commerce, Maastricht University, August 2007.

High and rising wages helping to preserve the traditional family structure is a major reason the family capitalism countries are more successful in ameliorating childhood poverty. In contrast, inopportunity and the absence of high-value jobs create unhelpful pathologies and a corrosive dynamic destabilizing families and family formation in America. That outcome is documented by an American rate of single-parent households that is 50 percent greater than in France and Germany.7 And researchers including Isabel Sawhill and Robert Lerman have determined that the rise in single-parent households accounts for most of the increase in childhood poverty since the 1970s.8 When combined with low minimum wages and weak public antipoverty support, the outcome is that American children are the poorest of all among rich nations. And Europeans know it, with headlines like this one in the epigraph appearing in Le Figaro:

“American children: the poorest in the developed world.”9

The Notten and de Neubourg study and similar analyses are strongly suggestive that the documented Reagan decline in high-wage jobs shortchanged the economic prospects, opportunity, and mobility of American families and their children. It leaves one-third of youngsters languishing in or near poverty when calibrated by the standard used by most other rich democracies, too many struggling in single-parent households, doomed to squandered lives of lost opportunity and frustration. No economic system should permit the loss of up to one-third of its human resource, particularly since a superb model for maximizing human capital has evolved in other rich capitalist democracies.

Research and statistics on childhood poverty document that America during the Reagan decline failed to meet the Rawls test. Has it performed any better in addressing the two other groups historically most disadvantaged by market economies—the working poor and school dropouts?

The Working Poor

Families unable to escape poverty despite working fulltime blight any economic system. Unlike most other rich democracies, America chooses not to provide those who work with a wage sufficient to avoid impoverishment. Indeed, its wage structure causes taxpayers to subsidize low-wage employers. Even working full-time, the American minimum wage does not lift a single parent and child above even the de minimus Orshansky threshold. In 2010, for example, a minimum wage paycheck for working the US average of 1,800 hours would have earned $2,000 less than the poverty level for a two-person family.

How many working poor are there? BLS determined some 10.5 million working Americans lived below the official US poverty line in 2010.10 And, including the near poor, recall that MIT economist Osterman determined in August 2011 that nearly one in five working adults was mired in poverty-level jobs paying the minimum wage or little better. International measures based on more demanding standards place the figure higher still. For example, statistics from the International Labor Organization show that one in four working Americans in 2010, some or many of them full-time workers, were considered to be working poor by international standards. They earned less than two-thirds the median wage threshold standard adopted by the United Nations for impoverishment.11

What is the lifestyle of this bottom 20 percent or more of our neighbors? Working full-time at the minimum wage in America in 2013 means earning a bit less than $1,100 a month. That income must cover comprehensive expenses for housing, food, transportation, health care, and everything else. It means a hand-to-mouth existence reliant on public transportation, shared housing, food stamp allotments, free school meals, little if any savings, scant health coverage, high-credit costs from usurious payday lenders, little or no worksite upskilling, prey to unscrupulous employers, and the continual stress of a grinding paycheck-to-paycheck life frequently featuring two jobs and inattention to children. It means the harrowing life evocatively described by Barbara Ehrenreich in her 2001 bestseller, Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America.

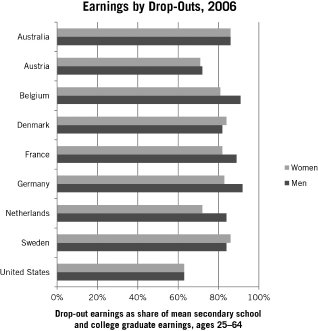

Dropouts

The other sizable component of the most disadvantaged is school dropouts. Sizable dropout cohorts are a problem in every rich democracy. The Scandinavian countries do a better job than Australia, France, Germany, or the United States of retaining youths in school and minimizing their number. Yet, because of their higher-wage structures, earnings by dropouts approach middle-class wages in the family capitalism countries. That is less true in America, as indicated by statistics in Chart 24.2, reproducing OECD data from 2006 (see next page). Indeed, dropouts in America bear the most severe earnings penalty of any rich democracy, receiving less than two-thirds (63 percent) the average wages for high school and university graduates in 2006. In contrast, German male dropouts earned 93 percent of what graduates earned, nearly a 50 percent larger share than in America. And in a global first, female drop-outs in Denmark and Sweden out-earn male dropouts.

Chart 24.2.

Source: “Education at a Glance,” Table A9.1a, OECD, Paris, 2008.