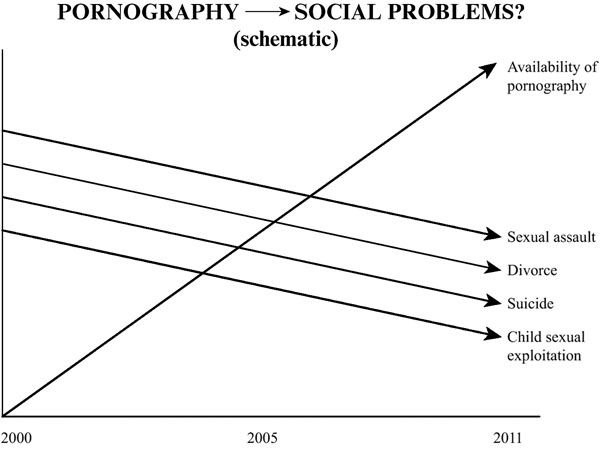

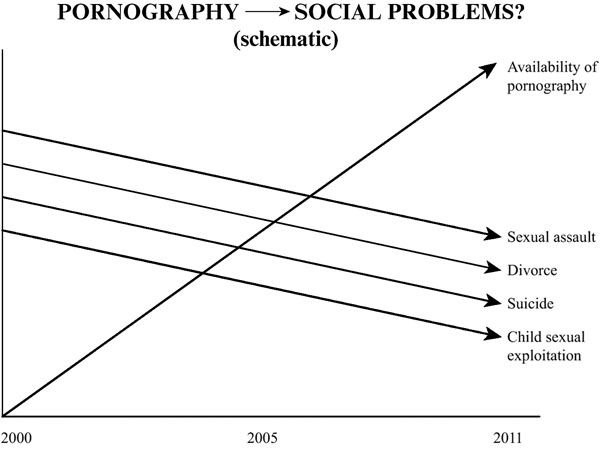

Figure 12.1. Effects of Increased Pornography Use

When Attorney General Alberto Gonzales announced the new federal war on pornography in 2005, with increased funding and reassignment of eight full-time FBI agents, one law enforcement veteran snidely expressed what a lot of people were thinking: “I guess we’ve won the war on terror.”1

We hadn’t, of course, so here’s a clue to the real payoff: According to the Washington Post, “Christian conservatives, long skeptical of Gonzales, greeted the pornography initiative with what the Family Research Council called ‘a growing sense of confidence in our new Attorney General.’ ”2

Prosecuting pornography was a political bone. The Bush administration, wanting to burnish the conservative credentials of its lagging Justice Department, threw the bone to the Right, which eagerly leaped for it.

Acquiring the support of the Family Research Council in exchange for simply limiting every American’s right to private entertainment must have seemed like a terrific deal to the Bush administration. Their war on porn was no more about making America’s families safer than was Ronald Reagan’s Meese Commission 20 years before it.

But restricting the amount and type of sexually explicit material you’re allowed to look at in private (and attempting to drive its producers and distributors out of business) is only one part of the battle against pornography. The other is a massive disinformation campaign—some of it sincere, much of it manipulative, and too much of it outright lies. This campaign has seduced, in no particular order, journalists, feminists, safety advocates, liberals—even small-government conservatives.

We’re not talking about porn that involves kids. No professional pornographer, no progressive sexologist, no libertarian, no sane person advocates involving actual children in the creation of pornography. Let’s agree this is not under discussion, and proceed.

Well, it would be nice if we could do that. Unfortunately, anti-porn activists focus obsessively on the alleged connection between adult porn and child porn, making an intelligent conversation difficult. As we’ll see later, there is no connection between the two.

In addition, anti-porn activists are obsessed with so-called “violent porn”—a heterogeneous category that mostly includes on-screen characters having fun playing with dominance and submission. Some of your neighbors play these sexual games, involving pain, surrender, intensity—and trust. Their faces may grimace, and their voices cry out, their bodies may look contorted or tormented. But millions of adults play like this, and so actors and actresses sometimes portray these games.

Screen characters can also portray violent, coercive behavior—some of it in porn films. Porn or not, most viewers know that the actors in these films are working under carefully controlled conditions—after all, it’s just a movie. And porn or not, extremely violent films are a sub-genre with limited appeal. Actually, a far larger percentage of mainstream films depict extreme violence than the percentage of porn films that depict extreme violence.

Both illegal child porn and legal extremely violent porn represent a tiny minority of the pornography that’s actually available and consumed by America’s 50 million porn viewers.

That leaves the rest of porn, in which actors portray happy male and female characters doing things they enjoy. Sometimes their fun involves stuff you find pleasurable that someone else might not: oral sex, spanking, anal toys, whatever. Occasionally these characters pursue activities you or your mate might not want to do: exhibitionism, playing with urine, group sex, whatever. Either way, the overwhelming majority of porn portrays consenting, enthusiastic men and women doing things they enjoy. These are activities routinely indulged in by tens of millions of Americans, sexual activities that couples go to marriage counselors to get more comfortable with.

So when a discussion about porn turns to “extremely violent porn” or “kiddie porn” or “bestiality,” these are not representative of mainstream adult material. Condemning all porn because of these exotic subgenres is like eliminating all TV because The Three Stooges is stupid or The Sopranos is violent. When you hear or participate in a conversation about pornography, see if the other person can talk without referring to porn “addiction,” child porn, brutal porn, or mass murder. If they can’t, they’re not discussing pornography, or even sex; they’re discussing violence, power, sadism, and fear.

And the extremely violent porn that a tiny sliver of consumers enjoys? It is disturbing that some people get pleasure or relief from watching such images. But it isn’t a reminder that porn is bad. It’s a reminder that human sexuality—like human psychology in general—is complex, some of it quite dark. Our society hasn’t come to terms with this, and so it wars on the material that supposedly creates this darkness. That’s willfully naïve. Every society has people who resonate with violent imagery, whether it’s a porn film, a bullfight, Indy car crashes, or the experience of war. Fortunately, most people who resonate with violent porn (or bullfights, or other violent imagery) don’t act out their response.

The war on porn is a war on people—people who look at porn. The government and conservative groups talk about “pornographers” and “hard-core smut,” but rarely about consumers of adult pornography—which total some 50 million Americans. To put that in perspective, The Daily Show gets about 2 million viewers in a typical week, and David Letterman gets about 4 million. About 30 million Americans have seen a Harry Potter film in a theater.

Clearly, adult pornography is mainstream entertainment. And obviously, all its 50 million viewers aren’t “porn addicts,” psychopaths, or child molesters. But claiming they are opens the door for a wide range of attacks on pornography. For many people, this public attacking behavior is driven by private emotional issues.

Americans are anxious about their sexual “normality” and competence, and about the impact of modern life on their relationships and their kids. Many of us are taught to feel guilty about our sexual desires, fantasies, and bodies, and this shame leads to secrecy, which complicates things. There may be no easy answers, but people still want their anxiety and emotional isolation to go away.

We want our kids to be sexually healthy, but we don’t know how to talk with them—and the sexualized media scare us. We want our sexual relationships to be enjoyable and nourishing, but we don’t know how to talk with our mates, and what we’re told about everyone else’s sex lives scares us.

In this context of emotional vulnerability, people welcome simple explanations that identify clear villains and provide clear solutions. The clergy, our government, the media, feminist groups, and “morality groups” insist that porn is the villain, and fighting porn is the answer. You’ve observed that many Americans love this. People in pain love knowing that there’s a “them” to blame and an “it” to attack.

The war on porn is a psychologically perfect solution to the confusion, anger, self-criticism, and shame that many Americans feel about sexuality and modern life. It’s short-sighted, futile, self-destructive, undignified, and disempowering. But it provides an explanation, a target, and hope. It’s a public policy solution to a private emotional problem. And it empowers and emboldens leaders and institutions who manipulate the public into thinking that sexuality is the problem, when sexual self-acceptance, flexibility, skills, and knowledge are the answer.

The war on pornography is also a handy activity for people who use porn and feel ashamed, guilty, and afraid of God’s judgment. Like anti-prostitution crusaders who see hookers, or anti-gay activists found in gay bars, many anti-porn advocates are simply trying to distance themselves from their own impulses. These people deserve sympathy, not a place at the public policy table.

Pornography is the repository of our culture’s ambivalence and negativity about sex (e.g., Americans watch porn, but pretend they don’t. They masturbate, but pretend they don’t).

Porn contains, for the most part, portrayals of conventional (many would say “normal”) sex—intercourse, oral sex, masturbation, orgasm, vibrators, anal sex, power games. Nevertheless, our society damns these portrayals—which are the record of, and therefore the acknowledgement of, our fantasy, desire, and participation. Porn is the opposite of the closet, of our culture’s shame about sexuality. And so those who speak from ambivalence or negativity angrily confront those who use porn: “It’s bad enough that you enjoy lusty sex. If you can’t have the decency to feel guilty about your sexuality, you certainly don’t have to celebrate it, much less deliberately inflame your desire!”

It’s not simply that so many of us are uncomfortable about sexuality. It’s the relationship that individuals and the culture have with that discomfort. The discomfort does not get discussed honestly, nor do most people feel in any way obligated to resolve these feelings. Instead, the discomfort is considered normal and fixed, and the objects of the discomfort—pornography, along with sexual words, music, art, and expression—are considered “bad” and expendable.

This is one reason that pornography is demonized. People want to conceptualize and describe it as being far enough away from what’s “normal” so that there’s no question about which has to change—the objects of the discomfort, not the discomfort itself. The demonization of pornography is a way of ending any dialogue before it really starts. If you defend or even accept pornography, you’re saying the equivalent of “I’m selfish, ignorant, misogynist, and perverted.”

There should be room in America’s ongoing discourse for discussing people’s pain about pornography, and our concern about some of our neighbors’ usage of it. But it is unacceptable to make that the only conversation about pornography. The government has taken that position strongly, which is cynical, dishonest, and destructive. It would be like making anorexia and bulimia the center of every discussion about nutrition or weight control.

To put it another way, if all we have is the wrong conversation about pornography, we end up eliminating a lot of sexual expression, at a social, psychological, and constitutional cost that’s unacceptable. It’s the equivalent of burning down a house to fumigate it.

Here are some of the ways government and anti-porn forces are warring on pornography and those who view it.

Another approach to the sale of legal adult magazines comes from pro-censorship “feminists,” such as Melissa Farley. In 1985, she began a National Rampage Against Penthouse with colleague Nikki Craft, which was a campaign of public destruction of bookstore-owned copies of Penthouse and Hustler. Farley was arrested 13 different times in 9 different states for these actions.5

In September 2011, Dr. Calum Bennachie filed a complaint against Farley with the American Psychiatric Association, asking that her membership be revoked due to numerous alleged violations of ethical research standards and misrepresentation of data.6

Today, local groups periodically picket stores that sell porn magazines or DVDs. They often photograph patrons or their license plates to discourage them from entering. In 2006, a campaign like this was instigated by actor Stephen Baldwin in Nyack, New York. The American Family Association’s Web site even has instructions on how to do this, including suggested messages on picket signs.7

Tamie Dragone, for example, was detained by police in Salina, Kansas, when a Wal-Mart photo clerk decided a semi-nude photo she took of her three-year-old was suspicious. Teresa and Charlie Hanraty were jailed in Raleigh, North Carolina, over a photo of him kissing their baby’s naval; they lost custody of their two children. And in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in a single month, not one but two computer shops called law enforcement over alleged child porn. After examining the owners’ private property—no warrant necessary—the computers, and owners, were cleared.

The American porn industry neither makes nor distributes erotic material knowingly featuring underage performers. Anyone who says otherwise is a liar and should be asked to provide proof. The War on Sex is full of liars who raise blood pressures—and millions of tax-deductible dollars—lying about this.

The underage material available in the U.S. today is either (1) amateur stuff made by individuals and distributed surreptitiously or (2) made by foreign producers in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia, with no affiliation to American businesses. Thus, further regulating the American adult industry will have no effect whatsoever on the amount of underage porn available in the United States. It may make legislators look good and constituents feel good, but it will not decrease the availability of, nor the appetite for, the material that everyone agrees is illegal and unconscionable.

In fact, in 1996, the American adult industry established the Association of Sites Advocating Child Protection (ASACP), a nonprofit organization dedicated to eliminating child pornography from the Internet. ASACP’s efforts include a reporting hotline for Web surfers and Web masters, rewards for accurate reporting/conviction of those responsible for child porn, strict standards for American adult Web sites, and proactive educational campaigns about age verification and other topics. During its existence, ASACP has received over a half-million reports of suspected child pornography sites. Virtually all (99.9%) of these reports can be attributed to non-adult Web masters, amateur collectors, or pedophiles, not professional adult companies.12

Given today’s political and economic realities, no one could be more interested in the elimination of child porn than the U.S. adult industry. It is fascinating to observe how the most ridiculous rumors to the contrary are so persistent, for example, that porn is marketed to children. Since children have no credit cards with which to purchase porn, why on earth would marketing target them?

Anti-porn activists also consistently spread the falsehood that watching adult porn leads to desiring and watching kiddie porn. If this is true, how do activists explain the following?

Activists point to the fact that some men caught with child pornography also consume adult pornography. Of course they do. If you take any random 1,000 male customers of United Airlines or Hertz Car Rentals, you’d discover that a large percentage of them consume adult pornography as well.

Is America soft on kiddie porn? Hardly. Current federal law criminalizes:

This is, of course, in addition to the completely redundant, totally symbolic (and expedient for the politicians who passed them) child pornography laws in each of the 50 states.

And if you think this legislative overkill is insufficient, you’ll love House Bill 1981, which came out of committee on July 28, 2011. Called the Protecting Children From Internet Pornographers Act of 2011 (which is an immediate tipoff that it’s about the politics of moral panic, not actual protection), it requires every Internet service provider to track all of your Internet activity and save it for 18 months, along with your name, credit card numbers, and the IP addresses you’ve been assigned. Not because you’ve done anything wrong, but because this massive intrusion into the personal lives of 100 million Americans might catch a handful of traders in child porn. The Atlantic calls this mandatory tracking of innocent Americans “arguably the biggest threat to civil liberties now under consideration in the United States.”13 The Electronic Frontier Foundation calls the bill “ripe for abuse by law enforcement officials,” creating “a perfect storm for government abuse.”

Those who wish to limit or ban pornography have cleverly positioned it (and thus, fighting it) as a public health issue. We hear, for example, about its supposed co-morbidities (fear of intimacy, low self-esteem, perversion); supposed effects on consumers (addiction, depression, isolation, disrespect for women); supposed impact on communities (increased violence, divorce, tumbling morals)—and the ultimate health issue, that it’s supposedly bad for kids.14

It’s a familiar model, generally accompanied by a familiar imperative: do what’s necessary to clean up the threat and protect our kids and communities, even if it costs a bundle and involves curtailing a few rights. As anthropologist Carole Vance says, “Every right-winger agrees that porn leads to women’s inequality—an inequality that doesn’t bother him in any other way.”15

In this context, discussing pornography as a free speech or civil rights issue can sound rather unconvincing and even naïve to many people. In some ways, this reflects a deeper problem with our society; while health and safety problems easily acquire special public policy cachet, many Americans seem to feel that free expression and civil rights are less important than almost anything else under discussion.16

For starters, the manipulative, extreme claims of the public health model should be challenged. Instead of apologizing or rolling our eyes, we must loudly say that science has not shown that adult material causes these awful consequences. In the same way that coffee often accompanies divorce, it’s true that many personal and community difficulties coexist with adult material. That’s because the use of adult material is so widespread, not because it typically causes problems.

And just like there’s healthy food and fattening food, safe beaches and beaches dangerous for inexperienced swimmers, there’s healthy porn and porn that might not be good for someone. Of course, that depends primarily on the consumer; just like green peppers are hard for a few people to digest and easy for most everyone else, most porn consumers have no trouble “digesting” what they view. The fact that a tiny percentage of viewers have personality disorders is no more reason to banish porn from everyone than the fact that some people can’t digest dairy products is good enough reason to remove half-and-half and Häagen-Dazs from supermarkets.

Just like there’s such a thing as moderate drinking, there’s such a thing as moderate porn use. And while some people can’t handle even one or two drinks, most adults can—and they are allowed to. Americans even have the right to drink to excess—as long as they don’t behave in dangerous ways. We must challenge the idea that all use of porn is abuse of porn (and therefore hazardous). It isn’t.

That said, we should be sympathetic about people’s fear of porn. The American public of non-porn viewers has been traumatized by repetitive, lurid stories of children molested at psychotic orgies; women raped, enslaved, and trafficked; normal men who become drooling, unproductive idiots; loving families destroyed—all because somebody watched an X-rated DVD. Let’s agree that such stories, although untrue, are scary, and that the fear they engender naturally demands action. Let’s appreciate the psychological and citizenship skills it would take to resist that demand—from oneself, one’s neighbors, or one’s civic or religious leaders.

Realistically, only after this can we expect that a conversation about rights will be taken seriously. We must say over and over that we’re talking about our rights, not just “pornographers’ rights”; that the right to look at porn is directly related to the right to criticize the government, choose your own religion, and raise your kids free of interference, and how the wrong approach to porn will inevitably undermine everyone’s non-porn rights. We’ve already seen this with attempts to censor network TV airings of Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan, and with attempts to remove Harry Potter books from public school libraries because of their so-called satanic influence.

In India, people starve while cows roam the streets. It isn’t because they think steak is unhealthy, it’s because their religion forbids them to kill or consume animals they consider sacred. We may make fun of this. But at least they don’t pretend it’s a public health issue.

Framing the war on porn as a public health issue makes it easy to drive people to near-hysteria about this alleged epidemic. The government (supported by conservative feminists and the Religious Right) can then deflect attention from how it limits porn’s alleged bad effects (i.e., how it limits porn), because “nothing’s too good for our kids,” and “we need to do whatever it takes to secure the health of America.”

While this alleged epidemic rages, and frightened, angry people work overtime to keep porn away from our precious children, we should remind ourselves that there is still no evidence that seeing pictures of naked smiling people, or depictions of adult sex, or hearing words like “dick” have a harmful effect on children (or adults). Our technologically advanced, research-oriented society studies practically everything that might be risky—from polyester baby blankets to asbestos tile, high-fat meat, flu shots for the elderly, and driving while sleep-deprived. The government and Religious Right refuse to fund objective studies about the effects of pornography use on the general public. They obviously don’t trust what the results might be.

Teaching kids to fear sex, to be ashamed of their bodies, to be secretive about masturbation, to believe men and women are from different planets, to focus on avoiding disease instead of creating pleasure and understanding intimacy—every one of these is more dangerous than catching a glimpse of pubic hair. And all of these together—what some people consider normal childrearing—constitute a recipe for heartbreak, dysfunction, and erotic guilt.

Say we had been sitting around in 1999, speculating: “What do you suppose would happen if America was flooded with free, high-quality pornography for a decade?” Many “decency” advocates and danger-oriented feminists would have predicted absolute mayhem: more of every kind of dreadful social pathology, especially sexual violence and relationship disruption.

As it happens, a year later that’s the exact experiment America began. The arrival of high-speed broadband Internet into American homes immediately brought mass consumption of pornography. And indeed, the “decency” advocates and erotophobic activists tell us that this level of pornography use has brought America the very mayhem that they predicted: violence against women, abortion, and a collapse of the country’s morals.

Figure 12.1. Effects of Increased Pornography Use

The data, however, proves they’re wrong.

According to the FBI and other government sources, many leading indicators of social pathology have declined since much of the country became regularly involved in pornography (see Figure 12.1). While there’s no proof that increased use of pornography has led to these various (and welcome) declines, this data very clearly suggests that pornography use does not lead to these negative outcomes, contrary to the constant pronouncements of Morality in Media, Witherspoon Institute, Concerned Women for America, and others promoting today’s moral panic.

And by the way, why are all of these groups lying about the supposed ever-increasing amount of sexual violence in America, when the FBI says it’s been steadily declining for a decade?

Those who disapprove of pornography insist that it’s bad for us. Since neither research nor law enforcement can find any actual data supporting this belief, and so many people watch it without negative effects, the latest “proof” is “brain science,” which supposedly shows that porn damages our brain, affecting it like destructive drugs. Purveyors of this junk science include Judith Reisman (discoverer of our self-poisoning “erototoxins”), Marnia Robinson (who claims porn viewing changes men’s neurological wiring, leading to chronic erectile dysfunction), and Mary Anne Layden (“Porn addicts have more trouble recovering from their addiction than cocaine addicts”).17

Serious scientists consistently dismiss this alleged brain data. Of course the brain lights up when we look at porn. It also lights up when we look at a Rembrandt, a sunset, or a touchdown pass. Anyone who looks at porn when his or her brain isn’t lighting up has a real problem. And by the way—the actual data behind the claims of junk “neuroscience? As Robinson says, “read the stories on my Web site.” In the world of science and fact, we call these anecdotes—charming, but not useful.

In 1988, the federal government introduced a new law, quickly known as 2257. It required extraordinarily onerous and absolutely unique recordkeeping from the adult industry, with enormous penalties for the most trivial failures to comply. The regulations look exactly like a Soviet-style bureaucratic obstacle to free expression.

Ostensibly to eliminate (non-existent) underage performers from the business, the government demands that anyone producing Web sites, magazines, DVDs, or other sexual material collect and archive photo identification (indexing and cross-referencing every name each performer has ever used) for every nude photo disseminated. “Even if a couple is in their 60s, you have to prove they’re over 18,” says Robert McGinley, President of Lifestyles Organization. “Since they can’t just criminalize all sexy pictures, the government has created a new category of crime involving recordkeeping.”

What a sneaky, undignified way around the rights of free expression. While pornography itself can’t be criminalized, the government created a way to pursue legal production companies for inadequate recordkeeping. The law was struck down as unconstitutional on First Amendment grounds shortly after its passage.18 Since then, the discriminatory statute has been resurrected and challenged many times.

In 2005, the government introduced an even stricter new strategy for controlling the production and distribution of legal sexually explicit material. The Department of Justice decided that “secondary producers” (packagers of existing, legal, already-2257-compliant porn) were subject to the same recordkeeping requirements as the original producers. Overnight, hundreds of thousands of Web sites became illegal. A series of court battles ensued, which ended in 2010 with 2257 being upheld.

The 2257 Regulations have been the subject of multiple lawsuits. “The statute imposes heavy burdens on a broad category of protected speech, namely sexually explicit images, based solely on the basis of the content of that speech,” wrote the attorneys (including Louis Sirkin and Paul Cambria) who represented the plaintiffs in Free Speech Coalition v. Gonzales.19 The regulations “reach a vast amount of protected speech that not even arguably involves children, and which are outside the Government’s interest in controlling child pornography.”

The 2257 Regulations pretend to solve a problem that doesn’t exist—underage performers in commercial porn—in a way that just happens to create enormous operating burdens for the adult industry. The government shrugs and falls back on a favorite justification: eliminating child porn. Since virtually everyone supports this goal, those who challenge the law look like creeps. Even if that’s all 2257 accomplishes, the government wins.

But of course, the logistical nightmare of the regulations will force many smaller producers and distributors out of business (achieving the government’s primary, though unstated, goal), and it gives the government the unlimited right to examine and challenge the detailed operations of the rest. During the eight years that the government obsessively stalked retailer Adam & Eve (PHE, Inc. v. United States Department of Justice, 1990, United States v. PHE, 1992),20 it admitted that it saw harassment as a legitimate law enforcement tool when porn is involved. 2257 is the latest flavor of harassment.

“The government has the same data as ASACP. They must know that 99.9 percent of child porn has nothing to do with the professional adult industry,” says Joan Irvine, ASACP executive director. “The new 2257 rules will not stop the production or distribution of child pornography. Adult companies already comply with the current laws; the criminals involved in child porn don’t and never will. I wish the government would focus their time and financial resources on apprehending the real criminals, and truly saving children.”21

2257 and other attempts to curtail porn use are pointless, says University of California–Los Angeles Law School professor Eugene Volokh. No matter how much the U.S. government can curtail domestic porn distribution, foreign sites will take up the slack. “It’s not like Americans have some great irreproducible national skills in smut-making. And even if overall world production of porn somehow improbably falls by 75 percent, will that seriously affect the typical porn consumer’s diet? Does it matter whether you have, say, 100,000 porn titles to choose from, or just 25,000? The investment of major prosecutorial resources yields a net practical benefit of roughly zero.” 2257 won’t change that, but it will create plenty of dangerous constitutional precedents.

Of course the government, continues Volokh, can go after porn consumers. Set up phony sites to entrap American users, then arrest, prosecute, and lock them up. Seize their houses on the theory that it’s a forfeitable asset. Make each one register as a sex offender. That would reduce porn consumption. Is America ready to acknowledge what it would take to dramatically change the entertainment habits of one-quarter of the adult population?22

There’s an increasing—and creepy—association between America’s war on porn and its war on terrorism.

In 2004 and 2005, Chris Wilson operated a Web site from his Florida home, NowThatsFuckedUp.com. It offered pleasant amateur porn (and many discussion groups) for a small fee. One interesting feature was that American soldiers received free entry if they sent photos of themselves from Iraq or Afghanistan. Hundreds did—including grisly war-theatre photos that the government didn’t want Americans to see. Remember, this is while the news media were prohibited from showing the coffins of returning American soldiers, as well as battlefield scenes of Iraqi or American casualties.

So Wilson was singled out and busted for obscenity, for hosting a Web site of “free” Americans back home showing off their bodies and having consensual sex in front of the camera. He faced felony charges and 300 misdemeanor counts. He sat in jail two different times, went through two Pentagon investigations (his personal and business computers were shipped to Washington for a forensic examination), and had his home searched.

Facing possible new racketeering (!) forfeiture threats and serious prison time, he plea-bargained. His probation required that he close the site and shun nudity or sex on any future Web site. Wilson and his attorneys agree that the obscenity bust was used to disrupt the soldiers’ posting of photos, and to punish Wilson for inviting it.

In early 2006, the Department of Justice asked the four largest Internet search engines in America—Google, AOL, Yahoo!, and MSN—for “a random sample of one million URLs” and the text of every search made over a one-week period.23 The government wanted the information to help it impose tougher laws on Web sites with information believed to be harmful to minors. Known as “prior restraint,” this kind of censorship is prohibited by the U.S. Constitution.

When Google refused to comply, the Department of Justice sought a court order to force them. What gives the government the right to ask for this information? Why, the Patriot Act and other Homeland Security laws—which, an anxious public was told when these laws were passed, were not going to be used for precisely this kind of broad domestic surveillance.24

But such laws beg to be abused—and unauthorized sexual expression is the perfect vehicle with which the government can abuse them.

So on February 9, 2006, uniformed officers of Montgomery County’s Department of Homeland Security marched into a public library in Bethesda, Maryland, and announced that it was forbidden to use library computers to view pornography. They then challenged a patron about the Web site he was visiting and asked him to step outside. A courageous librarian intervened, the police came, and the Homeland defenders had to withdraw, clearly operating outside their authority.25

The unannounced, unrecorded “sneak-and-peak” searches of our homes, gadgets, and electronic data that will continue under the Patriot Act (in which the government does not have to tell you you’re under surveillance) require no prior justification. Our government has a history of feeling politically threatened by a broad range of sexual interests; the sexuality of Martin Luther King, Jr., John Lennon, Emma Goldman, Lenny Bruce, and Paul Robeson, among others, has been investigated.

Polysemicity is the concept that no text or visual image has only a single meaning. Meaning is supplied by the reader or viewer, and so texts and pictures can have as many meanings as beholders. Said another way, the same thing can mean very different things to different people. In fact, the same experience isn’t really the same experience to two different people. And offense is generated in the beholder and directed to the material, not the other way around.27

To John, ice cream is a treat to be enjoyed; if he eats it, he’s OK. To overweight, self-critical Sam, it’s a seductive adversary to be avoided; if he eats it, he’s a pig. To Sue, wearing a miniskirt is a desperate bid for attention; to Maria, it’s a statement of pride in her looks; to Linda, it’s a declaration of independence from her husband; to Joann, it’s a way to thumb her nose at the church; to Sarah, it’s a way to let men know she’s sexually available.

The vast majority of porn’s critics (and marriage counselors and porn addiction counselors) say they don’t watch or read porn. So how can they know what it portrays, much less how viewers interpret what they see or read? True, porn’s critics include a number of self-described ex-porn addicts. Are the reports of these self-described sick, compulsive, spiritually dead, self-destructive people the source of all the anti-porn movement’s information?

People who don’t view porn (who typically know very little about it) assume that the experience of viewers is the same as the experience a non-viewer would have. It’s easy to imagine a non-viewer—say, someone who’s never seen two women kissing, or done anal sex, or been ejaculated on, or had sex with the lights on—imagining that looking at porn is uncomfortable, gross, or perverse. It’s easy for that person to imagine that anyone acting in such a film is feeling humiliated or being coerced or hurt. And it’s easy for that person to imagine that anyone who enjoys looking at porn is emotionally troubled, angry at his wife, or sexually perverse—willing to be violent, coercive, exploitive, or worse.28

One reason the concept of “porn addiction” is so appealing is that it explains behavior—”I’m out of control”—that is otherwise hard for non-viewers to understand, or for viewers themselves to fully accept.

Anti-porn forces continually pontificate about porn viewers and the porn viewing experience. They tell us porn viewers are addicted, immature, anti-woman, intimacy-fearing, selfish, gullible, and of course, dangerous to children.

Perhaps these are the qualities non-viewers would have if they viewed porn. But characterizing America’s 50 million porn consumers this way is just nuts. What’s even crazier is the way this has become accepted as truth.

Although pornography is not a love story, it does tell some truths. Not literal truths—few of us look like porn actors and actresses—but more philosophical, eternal truths. Politically relevant truths. That’s why porn is ultimately subversive, a key reason that it’s under siege.

Although American media and culture obsess about sex, most of us live with simplistic, superstitious, anhedonic, fear- and danger-based concepts of eroticism. Many obvious sexual facts are denied, tabooed, and distorted. Examples include: virtually all children masturbate; virtually everyone has sexual interests; most people fantasize sexually (primarily about “inappropriate” partners or activities); and most people are curious about others’ bodies and sex lives.

Pornography tells a variety of truths about sex and gender to viewers who decipher what they’re seeing (i.e., the vast majority of consumers). These truths are far more important than the surgically enhanced breasts, abnormally big penises, and casual group sex that are staples of the genre (which when taken literally, of course, are misleading). These truths include:

These truths, of course, defy America’s dominant paradigm about sexuality. In the traditional view, external rules are important; body parts are clearly either sexual or non-sexual; “nice” and “nasty” eroticism are clearly distinguishable from each other; different, non-overlapping groups of people indulge in each; and eroticism is dangerous if people don’t control their arousal.

Consumers of pornography regularly visit an erotic world quite different than this. The truth that porn tells is that all people have the option of conceptualizing their sexuality any way they like. Social norms regarding age and beauty, religious norms about godly and ungodly sex, personal fears about acceptance, cultural myths about the human body, all of these are ignorable; none are inevitable. Each of us can triumph over the ways social institutions attempt to control our sexual experience.

Ironically, this paradigm of pornography’s truths is what sex therapists try to get couples to understand and install in their own lives. These professionals know that the keys to satisfying sexual relationships are self-acceptance and self-empowerment, not losing a few pounds, buying flowers, going away on vacation, or wild positions.

Porn’s subtexts of abundance and validation are as responsible for contemporary cultural resistance—that is, the war on porn—as its explicit presentations of sexual activity.

A new way in which pornography tells the truth even more radically is amateur porn, which has exploded via the democratic frenzy of the Internet. Millions of men and women across the globe are now photographing themselves during various sexual activities, uploading these photos onto personal and commercial Web sites, and inviting the entire computerized world to enjoy them.

The world’s largest amateur porn site, www.Voyeurweb.com, gets over 4 million unique visits a day. Every year, the site receives photos and videos from over 100,000 individuals and couples.29 And this is just one amateur Web site.

In contrast to most commercial pornography, common features of amateur porn include:

The conventional critique of pornography would not predict amateur porn’s meteoric popularity. These criticisms assert that the supernatural beauty of actresses is central, that the desultory domination of actress by actor is crucial, that spectacular genital friction is what viewers most envy and desire.

Amateur pornography turns these assumptions upside down. There are no actresses, only real women. These women aren’t pretending to be excited, they are excited. They aren’t flaunting impossibly perfect bodies, they are enjoying their bodies as they are—some of them gorgeous, most of them imperfect, many of them appealing only insofar as they are enthusiastic. Virtually all the women in amateur porn share that quality—enthusiasm. They are actually enjoying themselves: the activities, the violation of taboos, the exhibitionism. Clearly, there’s no coercion here.

In contrast to the typically grim, ideological anti-porn critique, our analysis of porn’s attraction and value would predict and can explain why amateur porn is such a rapidly growing genre. If the keys to porn’s popularity are validation of the viewer’s vision of erotic abundance, female lust, and the reasonableness of erotic focus, a viewer can experience those even more intensely when this validation comes not from actors but from real people. Rather than actors implying that the viewer isn’t alone, amateur photos and video show real people proving the viewer isn’t alone.

So what does the viewer of amateur porn see? Everyday folks being lusty, exhibiting themselves, and participating in an erotic community. It’s a community where sexuality is understood as wholesome even when it’s expressed in taboo ways.

And why does our culture resist these truths? Because the revolutionary implications of empowering people sexually challenge the cultural status quo. Pornography does this without even portraying sex exactly as most people experience it.

Pornography is an admission that human beings feel, imagine, and do what they do. In a culture committed to both hiding and pathologizing (and therefore shaming) sex as it really is, this admission isn’t polite. It’s subversive.

Ultimately, pornography’s truths are subversive because they claim that we can empower ourselves and create our own erotic norms. Political structures just hate when ideas or cultural products empower people. This is the recurring lesson of Copernicus, Guttenberg, Margaret Sanger, Lenny Bruce, Timothy Leary, and Martin Luther King, Jr. In the conventional fear/danger model, the genders are adversaries. Pornography shows a reconciliation of the war of the sexes, as it contains no adversaries. In most of it, everyone shares the same interests: passion, un-self-consciousness, self-acceptance, pleasure, and mutuality. Porn undermines the conventional scarcity-themed sexual economy and gender hierarchy; this is one of its most radical features, and is a big reason it attracts political opposition.

The massive popularity of pornography, and its consistent themes of female lust and male-female mutuality, testify to our pain about the conventional sexual economy. Taking porn on its own terms would require society to acknowledge this pain; such a cultural challenge makes pornography subversive.

Porn is subversive because it says that sex is not dangerous.

The format of America’s cultural conversation about pornography reveals a great deal.

What does this mean? Doesn’t anyone notice that there is an activity done by 50 million people that practically no one will stand up and defend? And that anyone who does defend it is personally attacked? Gun ownership is controversial, but both its practitioners and critics defend their positions passionately—each actually proselytizes, hoping to convert others. Drinking alcohol is demonstrably harmful for a percentage of drinkers and for innocent bystanders; but alcohol distributors extol their product enthusiastically, no one ever suggests banning it for adults, and all but the most destructive drinkers are considered normal or even cool.

So what does the current one-sided monologue mean? What does it mean when one part of society discusses the behavior (and consciousness) of the other, and the voice of that other is missing?

It means that we hear only about porn’s “victims.” It means anti-porn activists can maintain the illusion that porn is a pathetic activity for marginalized people. This isn’t healthy for our Republic’s integrity.

Every anti-porn fundraising appeal, every government hearing, every op-ed piece shouts that porn is everywhere, that it’s taken over, that it’s a multi-billion dollar industry. Then they say porn is “attempting” to be mainstream—as if it isn’t already. They say porn is on the margins of our culture trying to get in and infect “normal” society—while simultaneously complaining that everything is “pornified” and that we must “reclaim” our culture.

But to say that porn is simultaneously everywhere and marginalized is a willfully distorted interpretation of the reality critics themselves describe. With 50 million viewers, half of all Internet searches, $12 billion spent annually (more than all the tickets to professional baseball, basketball, and football combined), porn is the mainstream entertainment choice of America. The fact that most people won’t talk about their choice, and that non-viewers damn this choice, doesn’t change the fact. Viewing porn is a central American activity.

Why don’t porn consumers speak up when they hear themselves mocked, pitied, attacked, feared, dehumanized? When the fury of enraged neighbors is whipped up by the bully pulpits of the ignorant and authoritarian, and supported by the legal machinery of city and state—all arrayed against their choice of entertainment, which they experience as harmless?

It’s because people who consume porn have learned to hide it. You mention it to your neighbor, and maybe your kids can’t play there anymore. Your neighbor mentions it to his poker buddy, and maybe you lose a customer, or a promotion. If you suggest it to your wife and she watches Maury, Tyra, Nancy, Anderson, Geraldo, Katie, or Dr. Phil—or any show on the Christian Broadcasting Network or Trinity Broadcasting Network—you may regret it for the rest of your life.

Religious training has instilled a tremendous shame in many porn consumers. That doesn’t stop them from using it (guilt can actually drive usage),30 only from feeling comfortable about it—and feeling they have a legitimate right to it.

The unending, escalating propaganda about porn leading to violence and child endangerment means that defending the right to use porn (say, in a letter to the editor about a local vigilante group) invites the wrath of a righteous mob that no sane person wants. And with the successful demonization of “pornographers,” no one wants to be associated with those sub-humans.

Americans have had so many rights of expression, economic choice, and privacy for so long, that most have trouble envisioning their world without them. For people who enjoy a little porn once a week, it’s hard to imagine our country’s constitutional structure turning on such a seemingly trivial thing. The righteous anger of the Right, enthroned in federal and state government, clearly sees what the average porn consumer still doesn’t—the profound connection between the personal and the political.

Finally, we have to say that there’s more at stake in the war on porn than the right to look at a picture of a friendly lady’s nipples. It just so happens that sexuality/pornography is the vehicle of the moment in the eternal tug-of-war about the nature and meaning of the American system. At various times, that vehicle has been race (separate-but-equal; Japanese internment camps); age (child labor law, mandatory education); and private property rights (eminent domain, anti-discrimination law). Similarly, religion is another contemporary vehicle in this tug-of-war (stem-cell research, right-to-die, school vouchers, school prayer, Christmas displays on public property).

Pornography might not be the battlefield on which you or I would choose to defend secular pluralism, free expression, and science-based (as opposed to emotion-based) public policy. But as this is the battlefield that has been chosen for us, we must respond with energy and vision, neither apologizing nor acquiescing to manipulative descriptions of what porn is, who porn consumers are, or what the fight over porn is about.

The increasingly aggressive and confident attacks on porn are based on the following assumptions:

Resisting the War on Sex requires articulating these assumptions, discussing their importance to all Americans, and then challenging every single one. Those who want to eliminate porn justify their extreme proposals by saying that the stakes are too high for halfway measures or fey concerns about free expression. They’re absolutely right—the stakes are very, very high.