Critical Thinking

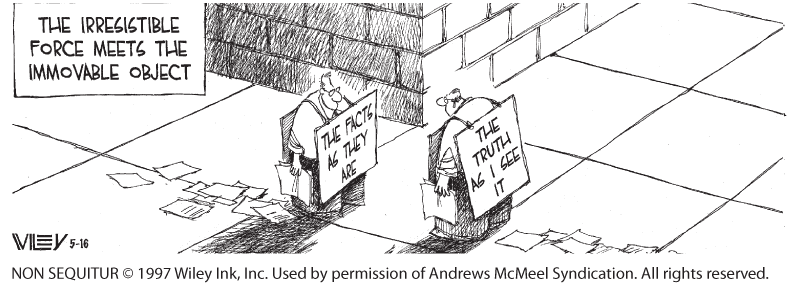

The scientific attitude—curiosity + skepticism + humility—prepares us to think harder and smarter. This thinking style, called critical thinking, examines assumptions, appraises the source, discerns hidden biases, evaluates evidence, and assesses conclusions. Whether reading a research report or an online opinion, or listening to news or a talk show, critical thinkers ask questions: How do they know that? What is this person’s agenda? Is the conclusion based on anecdote, or on evidence? Does the evidence justify a cause-effect conclusion? What alternative explanations are possible?

Critical thinkers wince when people make factual claims based on gut intuition: “I feel like climate change is [or isn’t] happening.” “I feel like self-driving cars are more [or less] dangerous.” “I feel like my candidate is more honest.” Such beliefs (commonly mislabeled as feelings) may or may not be true. Critical thinkers are open to the possibility that they might be wrong. Sometimes, they know, the best evidence confirms their intuitions. Sometimes it challenges them and beckons them to a different way of thinking.

Critical thinking, informed by science, helps clear the colored lenses of our biases. Consider: Does climate change threaten our future, and, if so, is it human-caused? In 2016, climate-action advocates interpreted record Louisiana flooding as evidence of climate change. In 2015, climate-change skeptics perceived North American bitter winter cold as discounting global warming. Rather than having their understanding of climate change swayed by recent weather, critical thinkers say, “Show me the evidence.” Over time, is the Earth actually warming? Are the polar ice caps melting? Are vegetation patterns changing? And is human activity emitting atmospheric CO2 that would lead us to expect such changes?

When contemplating such issues, critical thinkers will also consider the credibility of sources. They will also look at the evidence (Do the facts support them, or are they just makin’ stuff up?). They will recognize multiple perspectives. And they will expose themselves to news sources that challenge their preconceived ideas.

From a tongue-in-cheek Twitter feed:

“ The problem with quotes on the Internet is that you never know if they’re true.”

Abraham Lincoln

Some religious people may view critical thinking and scientific inquiry, including psychology’s, as a threat. Yet many of the leaders of the scientific revolution, including Copernicus and Newton, were deeply religious people acting on the idea that “in order to love and honor God, it is necessary to fully appreciate the wonders of his handiwork” (Stark, 2003a,b)

Critical thinking can lead us to surprising findings. Some examples from psychological science: Massive losses of brain tissue early in life may have minimal long-term effects (see Module 12). Within days, newborns can recognize their mother by her odor (see Module 45). After brain damage, a person may be able to learn new skills yet be unaware of such learning (see Modules 31–33). Diverse groups—men and women, old and young, rich and middle class, those with and without disabilities—report roughly comparable levels of personal happiness (see Module 83).

“ My deeply held belief is that if a god anything like the traditional sort exists, our curiosity and intelligence are provided by such a god. We would be unappreciative of those gifts . . . if we suppressed our passion to explore the universe and ourselves.”

Carl Sagan, Broca’s Brain, 1979

As later modules illustrate, critical inquiry sometimes also debunks popular presumptions. Sleepwalkers are not acting out their dreams (see Module 24). Our past experiences are not all recorded verbatim in our brains; with brain stimulation or hypnosis, one cannot simply replay and relive long-buried or repressed memories (see Module 33). Most people do not suffer from unrealistically low self-esteem, and high self-esteem is not all good (see Module 59). Opposites tend not to attract (see Module 79). In these instances and many others, what psychological scientists have learned is not what is widely believed.

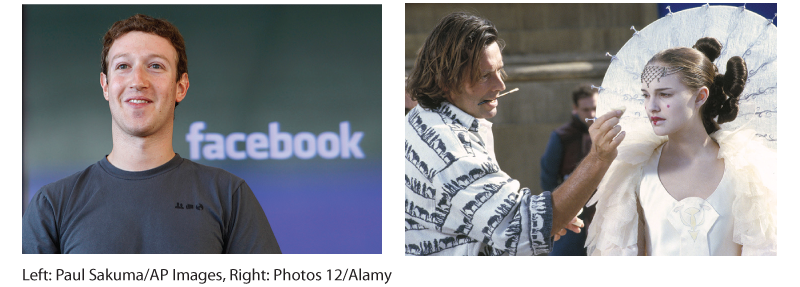

Life after studying psychology The study of psychology and its critical thinking strategies have helped prepare people for varied occupations, as illustrated by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (who studied psychology and computer science while at Harvard) and Natalie Portman (who majored in psychology and co-authored a scientific article at Harvard—and on one of her summer breaks was filmed for Star Wars: Episode I).

Psychology’s critical inquiry can also identify effective policies. To deter crime, should we invest money in lengthening prison sentences, or increase the likelihood of arrest? To help people recover from a trauma, should counselors help them relive it, or not? To increase voting, should we tell people about the low turnout problem, or emphasize that their peers are voting? What matters is not what we “feel” is true, but what is true. When put to critical thinking’s test—and contrary to common practice—the second option in each of this paragraph’s examples wins (Shafir, 2013).