Psychological Science Is Born

Psychology’s First Laboratory

Philosophers’ thinking about thinking continued until the birth of psychology as we know it. That happened on a December day in 1879, in a small, third-floor room at Germany’s University of Leipzig. There, two young men were helping an austere, middle-aged professor, Wilhelm Wundt, create an experimental apparatus. Their machine measured how long it took for people to press a telegraph key after hearing a ball hit a platform (Hunt, 1993). Curiously, people responded in about one-tenth of a second when asked to press the key as soon as the sound occurred—and in about two-tenths of a second when asked to press the key as soon as they were consciously aware of perceiving the sound. (To be aware of one’s awareness takes a little longer.) Wundt was seeking to measure “atoms of the mind”—the fastest and simplest mental processes. So began the first psychological laboratory, staffed by Wundt and by psychology’s first graduate students. (In 1883, Wundt’s American student G. Stanley Hall went on to establish the first formal U.S. psychology laboratory, at Johns Hopkins University.)

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) Wundt established the first psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig, Germany.

Psychology’s First Schools of Thought

Flip it Video: structuralism vs. Functionalism

Flip it Video: structuralism vs. Functionalism

Before long, this new science of psychology became organized into different branches, or schools of thought, each promoted by pioneering thinkers. These early schools included structuralism, functionalism, and behaviorism, described here (with more on behaviorism in Modules 26–30), and two schools described in later modules: Gestalt psychology (Module 19) and psychoanalysis (Module 55).

Structuralism

Soon after receiving his Ph.D. in 1892, Wundt’s student Edward Bradford Titchener joined the Cornell University faculty and introduced structuralism. Much as chemists developed the periodic table to classify chemical elements, Titchener aimed to classify and understand elements of the mind’s structure. He engaged people in self-reflective introspection (looking inward), training them to report elements of their experience as they looked at a rose, listened to a metronome, smelled a scent, or tasted a substance. What were their immediate sensations, their images, their feelings? And how did these relate to one another? Alas, structuralism’s technique of introspection proved somewhat unreliable. It required smart, verbal people, and its results varied from person to person and experience to experience. Moreover, we often just don’t know why we feel what we feel and do what we do. Research suggests that people’s recollections frequently err. So do their self-reports about what, for example, has caused them to help or hurt another (Myers, 2002). As introspection waned, so did structuralism.

Edward Bradford Titchener (1867–1927) Titchener used introspection to search for the mind’s structural elements.

Functionalism

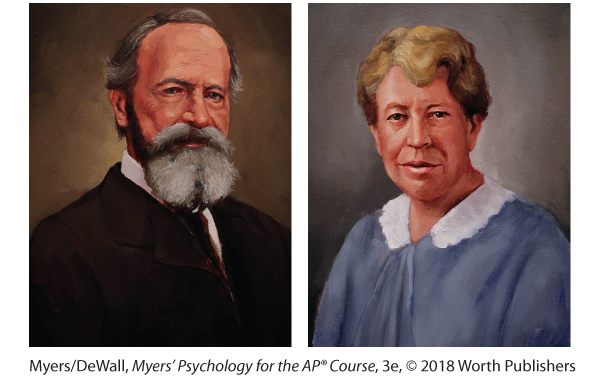

Hoping to assemble the mind’s structure from simple elements was rather like trying to understand a car by examining its disconnected parts. Philosopher-psychologist William James thought it would be more fruitful to consider the evolved functions of our thoughts and feelings. Smelling is what the nose does; thinking is what the brain does. But why do the nose and brain do these things? Under the influence of evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin, James assumed that thinking, like smelling, developed because it was adaptive—it helped our ancestors survive and reproduce. Consciousness serves a function. It enables us to consider our past, adjust to our present, and plan our future. As a functionalist, James studied down-to-earth emotions, memories, willpower, habits, and moment-to-moment streams of consciousness.

James’ greatest legacy, however, came less from his laboratory than from his Harvard teaching and his writing. When not plagued by ill health and depression, James was an impish, outgoing, and joyous man, who once recalled that “the first lecture on psychology I ever heard was the first I ever gave.” During one of his wise-cracking lectures, a student interrupted and asked him to get serious (Hunt, 1993). He loved his students, his family, and the world of ideas, but he tired of painstaking chores such as proofreading. “Send me no proofs!” he once told an editor. “I will return them unopened and never speak to you again” (Hunt, 1993, p. 145).

William James (1842–1910) and Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) James was a legendary teacher-writer who authored an important 1890 psychology text. He mentored Calkins, who became a pioneering memory researcher and the first woman to be president of the American Psychological Association.

James’ writings moved the publisher Henry Holt to offer James a contract for a textbook on the new science of psychology. James agreed and began work in 1878, with an apology for requesting two years to finish his writing. The text proved an unexpected chore and actually took him 12 years. (Why are we not surprised?) More than a century later, people still read the resulting Principles of Psychology (1890) and marvel at the brilliance and elegance with which James introduced psychology to the educated public.

Psychology’s First Women

James’ legacy stems from his Harvard mentoring as well as from his writing. In 1890, thirty years before American women had the right to vote, he admitted Mary Whiton Calkins into his graduate seminar—over the objections of Harvard’s president (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987). When Calkins joined, the other students (all men) dropped out. So James tutored her alone. Later, she finished all of Harvard’s Ph.D. requirements, outscoring all the male students on the qualifying exams. Alas, Harvard denied her the degree she had earned, offering her instead a degree from Radcliffe College, its undergraduate “sister” school for women. Calkins resisted the unequal treatment and refused the degree. She nevertheless went on to become a distinguished memory researcher and in 1905 became the first female president of the American Psychological Association (APA)—a national organization of professional and academic psychologists.

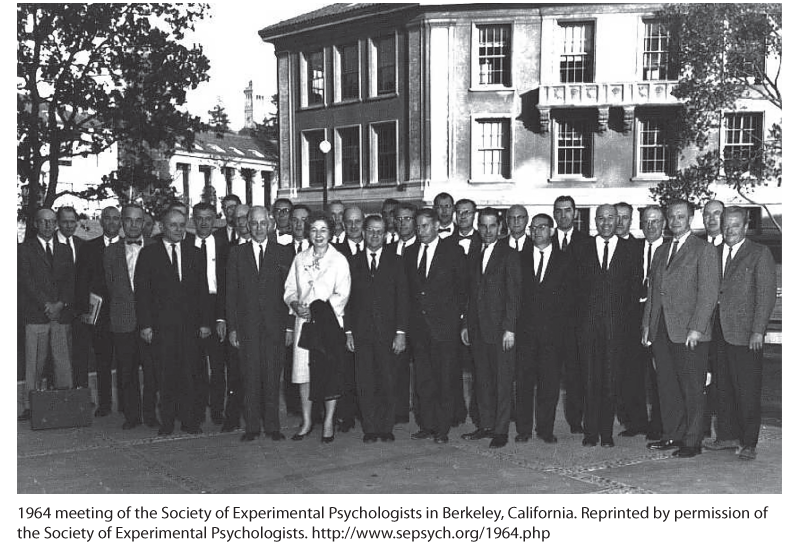

Formerly male and pale Over the past half century, psychology has shifted from a mostly white, male discipline to one where women now receive most Ph.D.s. Pioneering female psychologists, such as Inez Beverly Prosser (the first African-American woman to receive a psychology Ph.D., in 1933) and Eleanor Gibson (the only woman in this photo from the 1964 Society of Experimental Psychologists—the group that had barred Margaret Floy Washburn), helped pave the way. In 1971, Kenneth Clark became the APA’s first African-American president, and psychology has since then increasingly flourished in diverse communities around the world.

The honor of being the first official female psychology Ph.D. later fell to Margaret Floy Washburn, who also wrote an influential book, The Animal Mind, and became the second female APA president in 1921. Her thesis was the first foreign study Wundt published in his psychology journal, but Washburn’s gender barred doors for her, too. She could not join the all-male organization of experimental psychologists (who explore behavior and thinking with experiments), despite its being founded by Titchener, her own graduate adviser (Johnson, 1997). What a different world from the recent past—1997 to 2017—when women were 10 of the 20 elected presidents of the science-oriented Association for Psychological Science. In the United States, Canada, and Europe, most psychology doctorates are now earned by women.

Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) The first woman to receive a psychology Ph.D., Washburn synthesized animal behavior research in The Animal Mind (1908).