Reflections on Nature, Nurture, and Their Interaction

“There are trivial truths and great truths,” reflected the physicist Niels Bohr on the paradoxes of science. “The opposite of a trivial truth is plainly false. The opposite of a great truth is also true.” Our ancestral history helped form us as a species. Where there is variation, natural selection, and heredity, there will be evolution. The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg engulfed our father’s sperm predisposed both our shared humanity and our individual differences. Our genes form us. This is a great truth about human nature.

Culture matters As this exhibit at San Diego’s Museum of Man illustrates, children learn their culture. A baby’s foot can step into any culture.

But our experiences also shape us. Our families and peer relationships teach us how to think and act. Differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. If their genes and hormones predispose males to be more physically aggressive than females, culture can amplify this gender difference through norms that reward macho men and gentle women. If men are encouraged toward roles that demand physical power, and women toward more nurturing roles, each may act accordingly. Roles remake their players. Presidents in time become more presidential, servants more servile. Gender roles similarly shape us.

In many modern cultures, gender roles are merging. Brute strength has become less important for power and status (think “philanthrocapitalists” Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg). From 1965 to 2013, women soared from 9 percent to 47 percent of U.S. medical students (AAMC, 2014). In 1965, U.S. married women devoted eight times as many hours to housework as did their husbands; by 2012, this gap had shrunk to less than twice as many (Parker & Wang, 2013; Sayer, 2016). Such swift changes signal that biology does not fix gender roles.

* * *

If nature and nurture jointly form us, are we “nothing but” the product of nature and nurture? Are we rigidly determined?

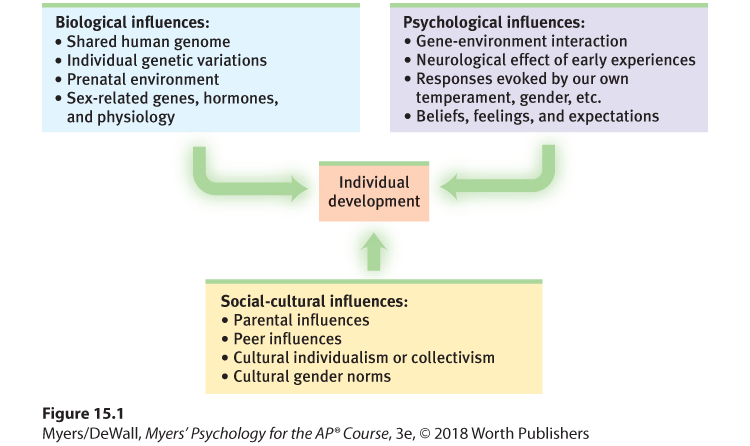

We are the product of nature and nurture, but we are also an open system, as suggested by the biopsychosocial approach (Figure 15.1; see Module 2). Genes are all-pervasive but not all-powerful. People may reject their evolutionary role as transmitters of genes and choose not to reproduce. Culture, too, is all-pervasive but not all-powerful. People may defy peer pressures and resist social expectations.

Figure 15.1 The biopsychosocial approach to development

Moreover, we cannot excuse our failings by blaming them solely on bad genes or bad influences. In reality, we are both creatures and creators of our worlds. So many things about us—including our gender identities and our mating behaviors—are the products of our genes and environments. Yet the stream that runs into the future flows through our present choices. Our decisions today design our environments tomorrow. The human environment is not like the weather—something that just happens. We are its architects. Our hopes, goals, and expectations influence our destiny. And that is what enables cultures to vary and to change. Mind matters.

* * *

We know from our correspondence and from surveys that some readers are troubled by the naturalism and evolutionism of contemporary science. “The idea that human minds are the product of evolution is . . . unassailable fact,” declared a 2007 editorial in Nature, a leading science journal. In The Language of God, Human Genome Project director Francis Collins (2006, pp. 141, 146), a self-described evangelical Christian, compiled the “utterly compelling” evidence that led him to conclude that Darwin’s big idea is “unquestionably correct.” Yet Gallup pollsters have reported that 42 percent of U.S. adults believe that humans were created “pretty much in their present form” within the last 10,000 years (Newport, 2014). Many people who dispute the scientific story worry that a science of behavior (and evolutionary science in particular) will destroy our sense of the beauty, mystery, and spiritual significance of the human creature. For those concerned, we offer some reassuring thoughts.

“ Let’s hope that it’s not true; but if it is true, let’s hope that it doesn’t become widely known.”

Lady Ashley, commenting on Darwin’s theory

When Isaac Newton explained the rainbow in terms of light of differing wavelengths, the British poet John Keats feared that Newton had destroyed the rainbow’s mysterious beauty. Yet, as evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins (1998) noted in Unweaving the Rainbow, Newton’s analysis led to an even deeper mystery—Einstein’s theory of special relativity. Nothing about Newton’s optics need diminish our appreciation for the dramatic elegance of a rainbow arching across a brightening sky.

“ Is it not stirring to understand how the world actually works—that white light is made of colors, that color measures light waves, that transparent air reflects light . . . ? It does no harm to the romance of the sunset to know a little about it.”

Carl Sagan, Skies of Other Worlds, 1988

When Galileo assembled evidence that the Earth revolved around the Sun, not vice versa, he did not offer irrefutable proof for his theory. Rather, he offered a coherent explanation for a variety of observations, such as the changing shadows cast by the Moon’s mountains. His explanation eventually won the day because it described and explained things in a way that made sense, that hung together. Darwin’s theory of evolution likewise is a coherent view of natural history. It offers an organizing principle that unifies various observations.

Many people of faith find the scientific idea of human origins congenial with their spirituality. In the fifth century, St. Augustine (quoted by Wilford, 1999) wrote, “The universe was brought into being in a less than fully formed state, but was gifted with the capacity to transform itself from unformed matter into a truly marvelous array of structures and life forms.” Some 1600 years later, Pope Francis in 2014 welcomed a science-religion dialogue, saying, “Evolution in nature is not inconsistent with the notion of creation, because evolution requires the creation of beings that evolve.”

Meanwhile, many people of science are awestruck at the emerging understanding of the universe and the human creature. It boggles the mind—the entire universe popping out of a point some 14 billion years ago, and instantly inflating to cosmological size. Had the energy of this Big Bang been the tiniest bit less, the universe would have collapsed back on itself. Had it been the tiniest bit more, the result would have been a soup too thin to support life. Astronomer Sir Martin Rees has described Just Six Numbers (1999), any one of which, if changed ever so slightly, would produce a cosmos in which life could not exist. Had gravity been a tad stronger or weaker, or had the weight of a carbon proton been a wee bit different, our universe just wouldn’t have worked.

What caused this almost-too-good-to-be-true, finely tuned universe? Why is there something rather than nothing? How did it come to be, in the words of Harvard-Smithsonian astrophysicist Owen Gingerich (1999), “so extraordinarily right, that it seemed the universe had been expressly designed to produce intelligent, sentient beings”? On such matters, a humble, awed, scientific silence is appropriate, suggested philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” (1922, p. 189).

Rather than fearing science, we can welcome its enlarging our understanding and awakening our sense of awe. In The Fragile Species, Lewis Thomas (1992) described his utter amazement that the Earth in time gave rise to bacteria and eventually to Bach’s Mass in B Minor. In a short 4 billion years, life on Earth has come from nothing to structures as complex as a 6-billion-unit strand of DNA and the incomprehensible intricacy of the human brain. Atoms no different from those in a rock somehow formed dynamic entities that produced extraordinary, self-replicating, information-processing systems—us (Davies, 2007). Although we appear to have been created from dust, over eons of time, the end result is a priceless creature, one rich with potential beyond our imagining.

“ The causes of life’s history [cannot] resolve the riddle of life’s meaning.”

Stephen Jay Gould, Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life, 1999

* * *

In this unit we have glimpsed an overriding principle: Everything psychological is simultaneously biological. We have focused on how our thoughts, feelings, and actions arise from our specialized yet integrated and wondrously adaptable brain. In modules to come, we will further explore the significance of the biological revolution in psychology.

From nineteenth-century phrenology to today’s neuroscience, we have come a long way. Yet what is unknown still dwarfs what is known. We can describe the brain. We can learn the functions of its parts. We can study how the parts communicate. But how do we get mind out of meat? How does the electrochemical whir in a hunk of tissue the size of a small cabbage give rise to elation, a creative idea, or that memory of Grandmother?

Much as gas and air can give rise to something different—fire—so also, believed Roger Sperry, does the complex human brain give rise to something different: consciousness. The mind, he argued, emerges from the brain’s dance of ions, yet is not reducible to it. As neuroscientist Donald MacKay (1978) observed, “[My brain activity] reflects what I am thinking, as [computer] activity reflects the equation it is solving.” The mind and brain activities are yoked, he noted, but are complementary and conceptually distinct.

“ All psychological phenomena are caused by the brain, but many are better understood at the level of the mind.”

Tweet from psychologist Steven Pinker, June 10, 2013

Cells cannot be fully explained by the actions of atoms, nor minds by the activity of cells. Psychology is rooted in biology, which is rooted in chemistry, which is rooted in physics. Yet psychology is more than applied physics. As Jerome Kagan (1998) reminded us, the meaning of the Gettysburg Address is not reducible to neural activity. Communication is more than air flowing over our vocal cords. Morality and responsibility become possible when we understand the mind as a “holistic system,” said Sperry (1992). We are not mere jabbering robots. Brains make thoughts. And thoughts change brains.

The mind seeking to understand the brain—that is indeed among the ultimate scientific challenges. And so it will always be. To paraphrase cosmologist John Barrow, a brain simple enough to be fully understood is too simple to produce a mind able to understand it.