Why Do We Sleep?

So, our sleep patterns differ from person to person and from culture to culture. But why do we have this need for sleep? Psychologists offer five possible reasons:

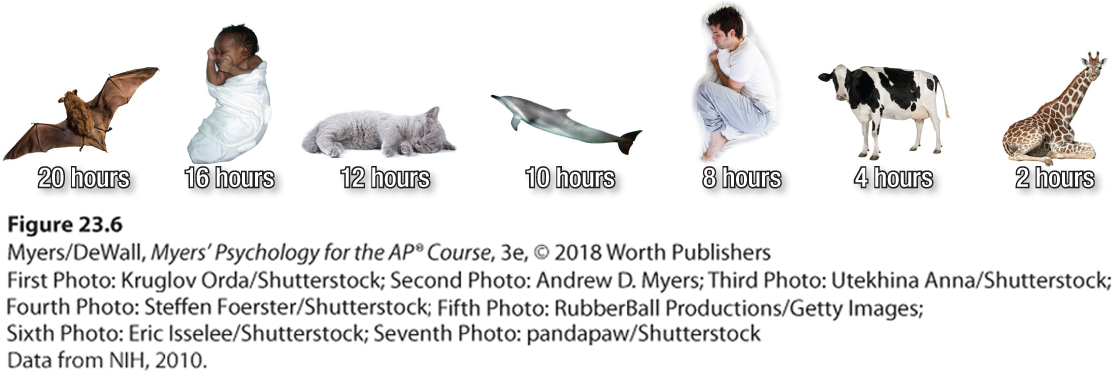

- Sleep protects. When darkness shut down the day’s hunting, gathering, and travel, our distant ancestors were better off asleep in a cave, out of harm’s way. Those who didn’t wander around dark cliffs were more likely to leave descendants. This fits a broader principle: A species’ sleep pattern tends to suit its ecological niche (Siegel, 2009). Animals with the greatest need to graze and the least ability to hide tend to sleep less. Animals also sleep less, with no ill effects, during times of mating and migration (Siegel, 2012). (For a sampling of animal sleep times, see Figure 23.6.)

- Sleep helps us recuperate. Sleep helps restore the immune system and repair brain tissue. Sleep gives resting neurons time to repair themselves, while pruning or weakening unused connections (Ding et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). Bats and other animals with high waking metabolism burn a lot of calories, producing free radicals, molecules that are toxic to neurons. Sleep sweeps away this toxic waste (Xie et al., 2013). Think of it this way: When consciousness leaves your house, workers come in to clean, saying “Good night. Sleep tidy.”

- Sleep helps restore and rebuild our fading memories of the day’s experiences. To sleep is to strengthen. Sleep consolidates our memories by replaying recent learning and strengthening neural connections (Pace-Schott et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2014). It reactivates recent experiences stored in the hippocampus and shifts them for permanent storage elsewhere in the cortex (Racsmány et al., 2010; Urbain et al., 2016). Adults, children, and infants trained to perform tasks therefore recall them better after a night’s sleep, or even after a short nap, than after several hours awake (Friedrich et al., 2015; Sandoval et al., 2017; Seehagen et al., 2015). Older adults’ more frequently disrupted sleep also disrupts memory consolidation (Boyce et al., 2016; Pace-Schott & Spencer, 2011). “Sleep less, think worse,” summarizes one research team (Frenda & Fenn, 2016). After sleeping well, older people remember more of recently learned material (Drummond, 2010). Sleep, it seems, strengthens memories.

“ Corduroy pillows make headlines.”

Anonymous

- Sleep feeds creative thinking. Dreams can inspire noteworthy artistic and scientific achievements, such as the dreams that clued chemist August Kekulé to the structure of benzene (Ross, 2006) and inspired medical researcher Carl Alving (2011) to invent the vaccine patch. More commonplace is the boost that a complete night’s sleep gives to our thinking and learning. After working on a task, then sleeping on it, people solve difficult problems more insightfully than do those who stay awake (Barrett, 2011; Sio et al., 2013). They also are better at spotting connections among novel pieces of information (Ellenbogen et al., 2007; Whitehurst et al., 2016). To think smart and see connections, it often pays to ponder a problem just before bed and then sleep on it.

- Sleep supports growth. During slow-wave sleep, which occurs mostly in the first half of a night’s sleep, the pituitary gland releases human growth hormone, which is necessary for muscle development.

Figure 23.6 Animal sleep time

Would you rather be a brown bat and sleep 20 hours a day or a giraffe and sleep 2 hours a day?

A regular full night’s sleep can “dramatically improve your athletic ability,” report James Maas and Rebecca Robbins (2010). REM sleep and NREM-2 sleep — which occur mostly in the final hours of a long night’s sleep — also help strengthen the neural connections that build enduring memories, including the “muscle memories” learned while practicing tennis or shooting baskets. Sleep promotes both a strong body and a strong mind. Well-rested athletes have faster reaction times, more energy, and greater endurance, and teams that build 8 to 10 hours of daily sleep into their training show improved performance. One study of Stanford University men’s basketball players found that when their average sleep increased 110 minutes per night over the course of several weeks, their sprint times decreased, and their free throw and 3-point shooting percentages both increased 9 percent (Mah et al., 2011). Swimmer Conner Jaeger, who won a silver medal at the 2016 Olympics, takes sleep seriously. “Part of our training that we really just started to focus on,” he said, “is sleep” (Mayberry, 2016).

Ample sleep supports skill learning and high performance This was the experience of Olympic gold medalist Sarah Hughes.

Maas, who has been a sleep consultant for college and professional athletes and teams, also advised basketball’s Orlando Magic and figure skating’s Sarah Hughes to cut their early-morning practices as part of a recommended sleep regimen. Soon thereafter, Hughes’ performance scores increased, ultimately culminating in her 2002 Olympic gold medal.