The Physiology of Sex

Sex is not like hunger, because it is not an actual need. Yet sex motivates. Had this not been so for all your ancestors, you would not be alive and reading these words. Sexual motivation is nature’s clever way of making people procreate, thus enabling our species’ survival. Life is sexually transmitted.

Hormones and Sexual Behavior

Among the forces driving sexual behavior are the sex hormones. The main male sex hormone is testosterone. The main female sex hormones are the estrogens, such as estradiol. Sex hormones influence us at many points in the life span:

- During the prenatal period, they direct our development as males or females.

- During puberty, a sex hormone surge ushers us into adolescence.

- After puberty and well into the late adult years, sex hormones facilitate sexual behavior.

“ Nature often equips life’s essentials—sex, eating, nursing—with built-in gratification.”

Frans de Waal, “Morals Without God?,” 2010

In most mammals, nature neatly synchronizes sex with fertility. Females become sexually receptive when their estrogens peak at ovulation, and researchers can cause female animals to become receptive by injecting them with estrogens. Male hormone levels are more constant, and hormone injection does not so easily affect the sexual behavior of male animals (Piekarski et al., 2009). Nevertheless, male hamsters that have had their testosterone-making testes surgically removed will gradually lose much of their interest in receptive females. They gradually regain it if injected with testosterone.

Hormones do influence human sexual behavior, but more loosely. Researchers are exploring and debating whether women’s mate preferences change across the menstrual cycle, especially at ovulation, when both estrogens and testosterone rise (Gildersleeve et al., 2014; Haselton & Gildersleeve, 2011, 2016; Wood et al., 2014a).

Women have much less testosterone than men do. And more than other mammalian females, women are responsive to their testosterone level (Davison & Davis, 2011; van Anders, 2012). If a woman’s natural testosterone level drops, as happens with removal of the ovaries or adrenal glands, her sexual interest may wane. And as experiments with surgically or naturally menopausal women have demonstrated, testosterone-replacement therapy can often restore diminished sexual activity, arousal, and desire (Braunstein et al., 2005; Buster et al., 2005; Petersen & Hyde, 2011).

In human males with abnormally low testosterone levels, testosterone-replacement therapy often increases sexual desire and also energy and vitality (Khera et al., 2011). But normal fluctuations in testosterone levels, from man to man and hour to hour, have little effect on sexual drive (Byrne, 1982). Indeed, male hormones sometimes vary in response to sexual stimulation (Escasa et al., 2011). In one study, Australian skateboarders’ testosterone surged in the presence of an attractive female, contributing to riskier moves and more crash landings (Ronay & von Hippel, 2010). Thus, sexual arousal can be a cause as well as a consequence of increased testosterone levels.

Large hormonal surges or declines affect sexual desire in shifts at two predictable points in the life span, and sometimes at an unpredictable third point:

- The pubertal surge in sex hormones triggers the development of sex characteristics and sexual interest. If puberty’s hormonal surge is precluded—as it was during the 1600s and 1700s for prepubertal boys who were castrated to preserve their soprano voices for Italian opera—sex characteristics and sexual desire do not develop normally (Peschel & Peschel, 1987).

- In later life, sex hormone levels fall. Women experience menopause as their estrogen levels decrease; males experience a more gradual change (Module 54). Sex remains a part of life, but as hormone levels decline, sexual fantasies and intercourse decline as well (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995).

- For some, surgery or drugs may cause hormonal shifts. When adult men were castrated, their sex drive typically fell as testosterone levels declined sharply (Hucker & Bain, 1990). Male sex offenders who took a drug that reduced their testosterone levels to that of a prepubertal boy similarly lost much of their sexual urge (Bilefsky, 2009; Money et al., 1983).

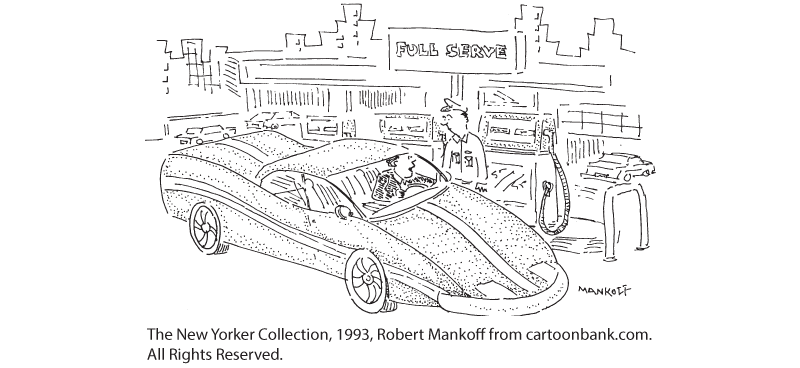

“Fill’er up with testosterone.”

To summarize: We might compare human sex hormones, especially testosterone, to the fuel in a car. Without fuel, a car will not run. But if the fuel level is minimally adequate, adding more won’t change how the car runs. The analogy is imperfect, because hormones and sexual motivation interact. However, it correctly suggests that biology is a necessary but incomplete explanation of human sexual behavior. The hormonal fuel is essential, but so are the psychological stimuli that turn on the engine, keep it running, and shift it into high gear.

The Sexual Response Cycle

The scientific process often begins with simple surveys of behavior, such as Indiana University biologist Alfred Kinsey did in questioning Americans about their sexuality and writing about their experiences. And then it moves to direct observations of complex behaviors. When gynecologist-obstetrician William Masters and his collaborator Virginia Johnson (1966) applied this process to human sexual intercourse in the 1960s, they made headlines. They recorded the physiological responses of volunteers who came to their lab to masturbate or have intercourse. (The volunteers, 382 females and 312 males, were a somewhat atypical sample, consisting only of people able and willing to display arousal and orgasm while scientists observed). Their description of the sexual response cycle identified four stages:

- Excitement: The genital areas become engorged with blood, causing a woman’s clitoris and a man’s penis to swell. A woman’s vagina expands and secretes lubricant; her breasts and nipples may enlarge.

- Plateau: Excitement peaks as breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates continue to increase. A man’s penis becomes fully engorged—to an average length of 5.6 inches among 1661 men who measured themselves for condom fitting (Herbenick et al., 2014). Some fluid—frequently containing enough live sperm to enable conception—may appear at its tip. A woman’s vaginal secretion continues to increase.

- Orgasm: Muscle contractions appear all over the body and are accompanied by further increases in breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates. The pleasurable feeling of sexual release is much the same for both sexes. One panel of experts could not reliably distinguish between descriptions of orgasm written by men and those written by women (Vance & Wagner, 1976). In another study, PET scans showed that the same subcortical brain regions were active in men and women during orgasm (Holstege et al., 2003a,b).

- Resolution: The body gradually returns to its unaroused state as the genital blood vessels release their accumulated blood. This happens relatively quickly if orgasm has occurred, relatively slowly otherwise. (It’s like the nasal tickle that goes away rapidly if you have sneezed, slowly otherwise.) Men then enter a refractory period that lasts from a few minutes to a day or more, during which they are incapable of another orgasm. A woman’s much shorter refractory period may enable her, if restimulated during or soon after resolution, to have more orgasms.