The Psychology of Sex

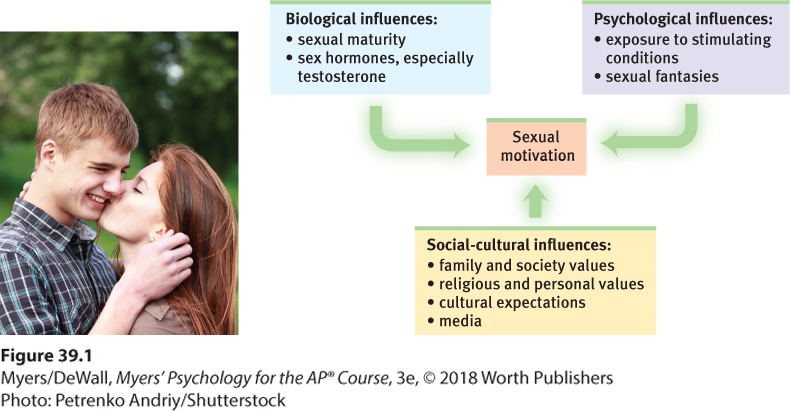

Biological factors powerfully influence our sexual motivation and behavior. Yet the wide variations over time, across place, and among individuals document the great influence of psychological factors as well (Figure 39.1).

Figure 39.1 Biopsychosocial influences on sexual motivation

Compared with our motivation for eating, our sexual motivation is less influenced by biological factors. Psychological and social-cultural factors play a bigger role.

External Stimuli

Men and women become aroused when they see, hear, or read erotic material (Heiman, 1975; Stockton & Murnen, 1992). In men more than in women, feelings of sexual arousal closely mirror their (more obvious) physical genital responses (Chivers et al., 2010).

People may find sexual arousal either pleasing or disturbing. (Those who wish to control their arousal often limit their exposure to arousing materials, just as those wishing to avoid overeating limit their exposure to tempting food cues.) With repeated exposure to any stimulus, including an erotic stimulus, the emotional response lessens, or habituates. During the 1920s, when Western women’s hemlines rose to the knee, an exposed leg made hearts flutter. Today, many would barely notice.

Can exposure to sexually explicit material have adverse effects? Research indicates that it can, in three ways.

- BELIEVING RAPE IS ACCEPTABLE. Depictions of women being sexually coerced—and appearing to enjoy it—have increased viewers’ belief in the false idea that women want to be overpowered, and have increased male viewers’ expressed willingness to hurt women and to commit rape after viewing such scenes (Allen et al., 1995, 2000; Foubert et al., 2011; Zillmann, 1989).

- REDUCING SATISFACTION WITH A PARTNER’S APPEARANCE OR WITH A RELATIONSHIP. After viewing images or erotic films of sexually attractive women and men, people have judged an average person, their own partner, or their spouse as less attractive. And they have found their own relationship less satisfying (Kenrick & Gutierres, 1980; Lambert et al., 2012). Perhaps reading or watching erotica’s unlikely scenarios creates expectations that few men and women can fulfill.

- DESENSITIZATION. Some studies have found that extensive online pornography exposure desensitizes young men to normal sexuality, thus contributing to erectile problems, lowered sexual desire, and diminished brain activation in response to sexual images. “Porn is messing with your manhood,” argue Philip Zimbardo and colleagues (2016). In one brain-imaging study, men who frequently watched pornography had smaller-sized brain regions that aid sexual pleasure (Kühn & Gallinat, 2014).

“ Ours is a society which stimulates interest in sex by constant titillation. . . . Cinema, television, and all the formidable array of our marketing technology project our very effective forms of titillation and our prejudices about man as a sexy animal into every corner of every hovel in the world.”

Germaine Greer, 1984

Imagined Stimuli

The brain, it has been said, is our most significant sex organ. The stimuli inside our heads—our imagination—can influence sexual arousal and desire. Lacking genital sensation because of a spinal cord injury, people can still feel sexual desire (Willmuth, 1987).

Both men and women (about 95 percent of each) report having sexual fantasies, which for a few women can, by themselves, produce orgasms (Komisaruk & Whipple, 2011). Men, regardless of sexual orientation (see Module 53), tend to have more frequent, more physical, and less romantic fantasies (Schmitt et al., 2012). They also prefer less personal and faster-paced sexual content in books and videos (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995).

Sex and Human Relationships

Surely one significance of such intimacy is its expression of our profoundly social nature. In one national study that followed participants to age 30, later first sex predicted greater satisfaction in one’s marriage or partnership (Harden, 2012). Another study asked 2035 married people when they started having sex (while controlling for education, religious engagement, and relationship length). Those whose relationship first developed to a deep commitment, such as marriage, not only reported greater relationship satisfaction and stability but also better sex (Busby et al., 2010; Galinsky & Sonenstein, 2013). For both men and women, but especially for women, sex is more satisfying (with less regret and more orgasms) for those in a committed relationship, rather than a brief sexual hook-up (Armstrong et al., 2012; Garcia et al., 2012, 2013). Commitment enhances contentment.