Gender, Emotion, and Nonverbal Behavior

Is women’s intuition superior to men’s, as so many people believe (Gigerenzer et al., 2014)? Do women have greater sensitivity than men to nonverbal cues? After analyzing 125 studies, Judith Hall (1984, 1987) concluded that, when given thin slices of behavior, women generally do surpass men at reading people’s emotional cues. The female advantage emerges early in development. Female infants, children, and adolescents have outperformed males in many studies (McClure, 2000). Women’s nonverbal sensitivity helps explain their greater emotional literacy. When invited to describe how they would feel in certain situations, men tend to describe simpler emotional reactions (Barrett et al., 2000). You might like to try this yourself: Ask some people how they might feel when saying good-bye to friends after graduating from high school. Research suggests you will be more likely to hear young men say, simply, “I’ll feel bad,” and to hear young women to express more complex emotions: “It will be bittersweet; I’ll feel both happy and sad.”

Women’s skill at decoding others’ emotions may also contribute to their greater emotional responsiveness and expressiveness (Fischer & LaFrance, 2015; Vigil, 2009). In studies of 23,000 people from 26 cultures, women more than men reported themselves open to feelings (Costa et al., 2001). Girls also express stronger emotions than boys do, hence the extremely strong perception that emotionality is “more true of women”—a perception expressed by nearly 100 percent of 18- to 29-year-old Americans (Chaplin & Aldao, 2013; Newport, 2001).

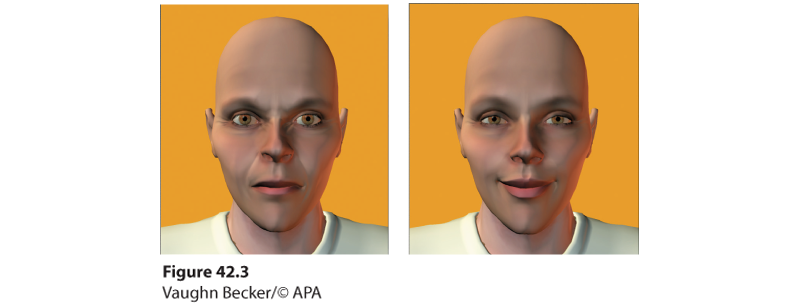

One exception: Quickly—imagine an angry face. What gender is the person? If you’re like 3 in 4 Arizona State University students, you imagined a male (Becker et al., 2007). And when a gender-neutral face was made to look angry, most people perceived it as male. If the face was smiling, they were more likely to perceive it as female (Figure 42.3). Anger strikes most people as a more masculine emotion.

Figure 42.3 Male or female?

Researchers manipulated a gender-neutral face. People were more likely to see it as male when it wore an angry expression and female when it wore a smile (Becker et al., 2007).

The perception of women’s emotionality also feeds—and is fed by—people’s attributing women’s emotionality to their disposition and men’s to their circumstances: “She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day” (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, 2009). Many factors influence our attributions, including cultural norms (Mason & Morris, 2010). Nevertheless, there are some gender differences in descriptions of emotional experiences. When surveyed, women are also far more likely than men to describe themselves as empathic. If you have empathy, you identify with others and appraise a situation as they do, rejoicing with those who rejoice and weeping with those who weep (Wondra & Ellsworth, 2015). Fiction readers, who immerse themselves in the lives of their favorite characters, report higher empathy levels (Mar et al., 2009). This may help explain why, compared with men, women read more fiction (Tepper, 2000). But physiological measures, such as heart rate while seeing another’s distress, reveal a much smaller gender gap (Eisenberg & Lennon, 1983; Rueckert et al., 2010).

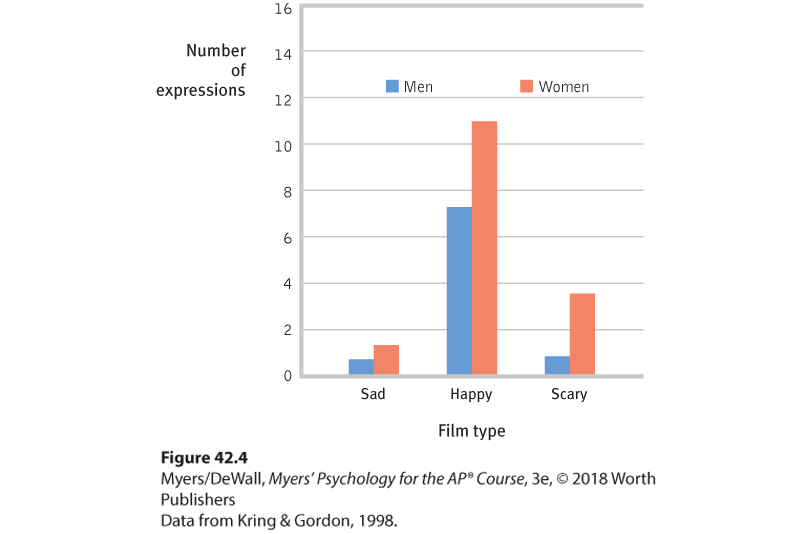

Females are also more likely to express empathy—to display more emotion when observing someone else’s emotions. As Figure 42.4 shows, this gender difference was clear when male and female students watched film clips that were sad (children with a dying parent), happy (slapstick comedy), or frightening (a man nearly falling off the ledge of a tall building) (Kring & Gordon, 1998). Women also tend to experience emotional events, such as viewing pictures of mutilation, more deeply and with more brain activation in areas sensitive to emotion. And they better remember the scenes three weeks later (Canli et al., 2002).

Figure 42.4 Gender and expressiveness

Male and female film viewers did not differ dramatically in self-reported emotions or physiological responses. But the women’s faces showed much more emotion.