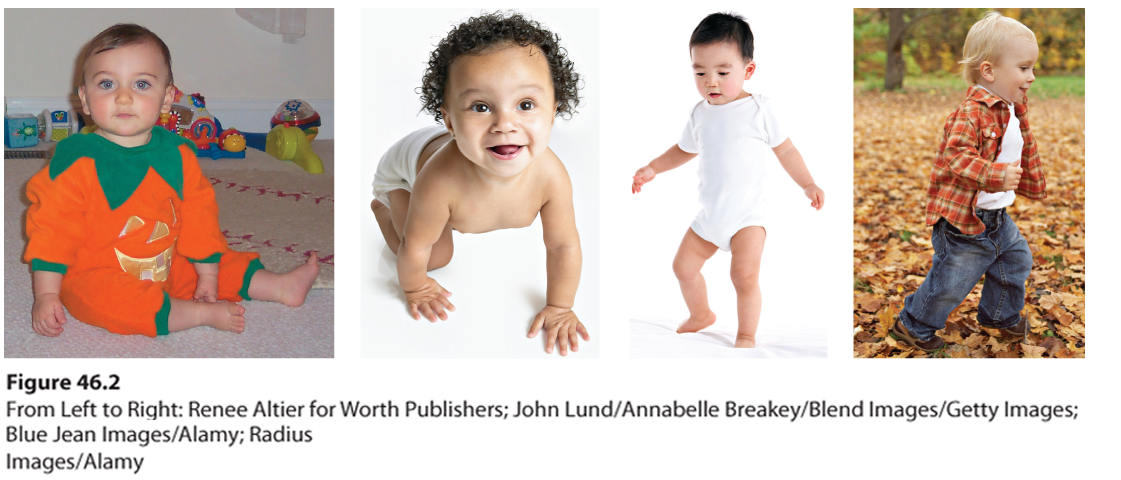

Motor Development

The developing brain enables physical coordination. Skills emerge as infants exercise their maturing muscles and nervous system. With occasional exceptions, the motor development sequence is universal. Babies roll over before they sit unsupported, and they usually crawl before they walk. These behaviors reflect not imitation but a maturing nervous system; blind children, too, crawl before they walk (Figure 46.2).

Figure 46.2 Triumphant toddlers

Sit, crawl, walk, run—the sequence of these motor development milestones is the same the world around, though babies reach them at varying ages.

Flip It Video: Major Developmental Milestones

Flip It Video: Major Developmental Milestones

Baby brains This “electrode cap” allows researchers to detect changes in brain activity triggered by different stimuli.

Genes guide motor development. In the United States, 25 percent of all babies walk by 11 months of age, 50 percent within a week after their first birthday, and 90 percent by age 15 months (Frankenburg et al., 1992). Identical twins typically begin walking on nearly the same day (Wilson, 1979). Maturation—including the rapid development of the cerebellum at the back of the brain—creates our readiness to learn walking at about age 1. The same is true for other physical skills, including bowel and bladder control. Before necessary muscular and neural maturation, neither pleading nor punishment will produce successful toilet training. You can’t rush a child’s first flush.

Still, nurture may amend what nature intends. In some regions of Africa, the Caribbean, and India, caregivers often massage and exercise babies, which can accelerate the process of learning to walk (Karasik et al., 2010). The recommended infant back to sleep position (putting babies to sleep on their backs to reduce crib-death risk) has been associated with somewhat later crawling but not with later walking (Davis et al., 1998; Lipsitt, 2003).

“This is the path to adulthood. You’re here.”