Experience and Brain Development

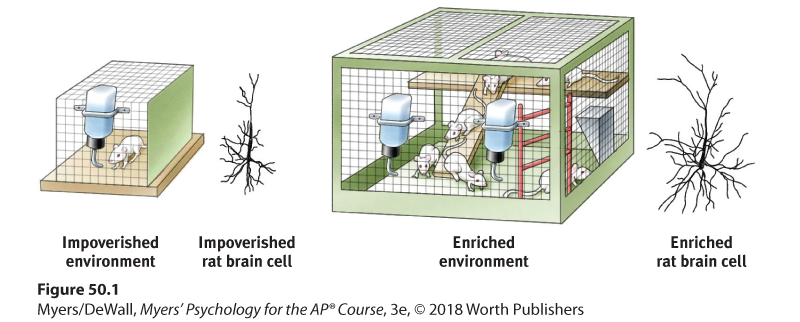

Developing neural connections prepare our brain for thought, language, and other later experiences. So how do early experiences leave their fingerprints in the brain? Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) opened a window on that process when they raised some young rats in solitary confinement and others in a communal playground. When they later analyzed the rats’ brains, those who died with the most toys had won. The rats living in the enriched environment, which simulated a natural environment, usually developed a heavier and thicker brain cortex (Figure 50.1).

Figure 50.1 Experience affects brain development

Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) raised rats either alone in an environment without playthings, or with other rats in an environment enriched with playthings that changed daily. In 14 of 16 repetitions of this basic experiment, rats in the enriched environment developed significantly more cerebral cortex (relative to the rest of the brain’s tissue) than did those in the impoverished environment.

Rosenzweig was so surprised that he repeated the experiment several times before publishing his findings (Renner & Rosenzweig, 1987; Rosenzweig, 1984). So great are the effects that, shown brief video clips of rats, you could tell from their activity and curiosity whether their environment had been impoverished or enriched (Renner & Renner, 1993). After 60 days in the enriched environment, the rats’ brain weights increased 7 to 10 percent and the number of synapses mushroomed by about 20 percent (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998). The enriched environment literally increased brain power.

Stringing the circuits young String musicians who started playing before age 12 have larger and more complex neural circuits controlling the note-making left-hand fingers than do string musicians whose training started later (Elbert et al., 1995).

Such results have motivated improvements in environments for laboratory, farm, and zoo animals—and for children in institutions. Stimulation by touch or massage also benefits infant rats and premature babies (Field et al., 2007; Sarro et al., 2014). “Handled” infants of both species develop faster neurologically and gain weight more rapidly. Preemies who have had skin-to-skin contact with their mothers sleep better, experience less stress, and show better cognitive development 10 years later (Feldman et al., 2014).

Nature and nurture interact to sculpt our synapses. Brain maturation provides us with an abundance of neural connections. Experience—sights and smells, touches and tastes, music and movement—activates and strengthens some neural pathways while others weaken from disuse. Similar to paths through a forest, less-traveled neural pathways gradually disappear and popular ones are broadened (Gopnik et al., 2015). By puberty, this pruning process results in a massive loss of unemployed connections.

Here at the juncture of nurture and nature is the biological reality of early childhood learning. During early childhood—while excess connections are still on call—youngsters can most easily master such skills as the grammar and accent of another language. Lacking any exposure to language before adolescence, a person will never master any language (see Module 36). Likewise, lacking visual experience during the early years, a person whose vision is later restored by cataract removal will never achieve normal perceptions (see Module 19) (Gregory, 1978; Wiesel, 1982). Without that early visual stimulation, the brain cells normally assigned to vision will die or be diverted to other uses. The maturing brain’s rule: Use it or lose it.

“ Genes and experiences are just two ways of doing the same thing—wiring synapses.”

Joseph LeDoux, The Synaptic Self, 2002

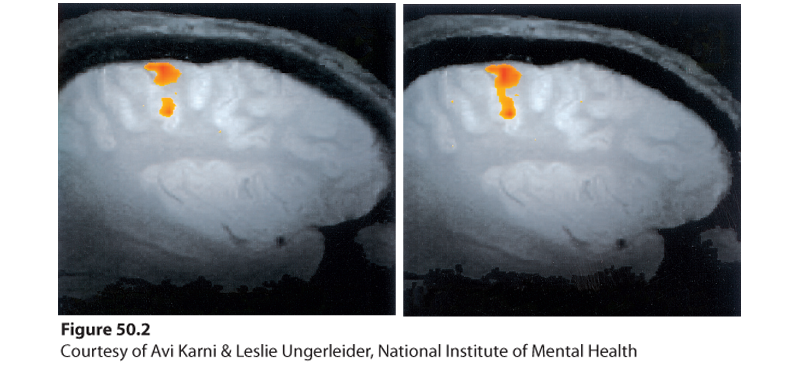

Although normal stimulation during the early years is critical, the brain’s development does not end with childhood. As we saw in Modules 9 and 12, thanks to the brain’s amazing plasticity, our neural tissue is ever changing and reorganizing in response to new experiences. New neurons are also born. If a monkey pushes a lever with the same finger many times a day, brain tissue controlling that finger will change to reflect the experience (Figure 50.2). Human brains work similarly. Whether learning to keyboard, skateboard, or navigate London’s streets, we perform with increasing skill as our brain incorporates the learning (Ambrose, 2010; Maguire et al., 2000).

Figure 50.2 A trained brain

A well-learned finger-tapping task activates more motor cortex neurons (orange area, right) than were active in this monkey’s brain before training (left). (From Karni et al., 1998.)