Parent and Peer Relationships

This next research finding will not surprise you: As adolescents in Western cultures seek to form their own identities, they begin to pull away from their parents (Shanahan et al., 2007). The preschooler who can’t be close enough to her mother, who loves to touch and cling to her, becomes the 14-year-old who wouldn’t be caught dead holding hands with Mom. The transition occurs gradually (Figure 52.1). By adolescence, parent-child arguments occur more often, usually over mundane things—household chores, bedtime, homework (Tesser et al., 1989). Conflict during the transition to adolescence tends to be greater with first-born than with second-born children, and greater with mothers than with fathers (Burk et al., 2009; Shanahan et al., 2007).

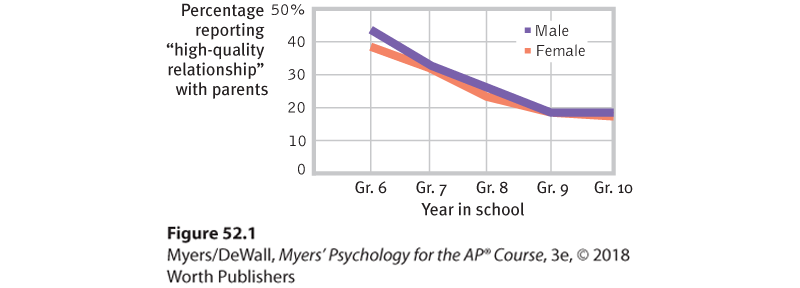

Figure 52.1 The changing parent-child relationship

In a large national study of Canadian families, the typically close, warm relationships between children and their parents loosened as they became teens (Pepler & Craig, 2012).

“She says she’s someone from your past who gave birth to you, and raised you, and sacrificed everything so you could have whatever you wanted.”

“ I love u guys.”

Emily Keyes’ final text message to her parents before dying in a Colorado school shooting, 2006

For a minority of parents and their adolescents, differences lead to real splits and great stress (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). But most disagreements are at the level of harmless bickering. With sons, the issues often are behavior problems, such as acting out or hygiene; for daughters, the issues commonly involve relationships, such as dating and friendships (Schlomer et al., 2011). Most adolescents—6000 of them surveyed in 10 countries, from Australia to Bangladesh to Turkey—have said they like their parents (Offer et al., 1988). “We usually get along but . . . ,” adolescents often reported (Galambos, 1992; Steinberg, 1987).

Positive parent-teen relations and positive peer relations often go hand in hand. High school girls who had the most affectionate relationships with their mothers tended also to enjoy the most intimate friendships with girlfriends (Gold & Yanof, 1985). And teens who felt close to their parents have tended to be healthy and happy and to do well in school (Resnick et al., 1997). Of course, we can state this correlation the other way: Misbehaving teens are more likely to have tense relationships with parents and other adults.

Adolescence is typically a time of diminishing parental influence and growing peer influence. Asked in a survey if they had “ever had a serious talk” with their child about illegal drugs, 85 percent of American parents answered Yes. But if the parents had indeed given this earnest advice, many teens had apparently tuned it out: Only 45 percent could recall such a talk (Morin & Brossard, 1997).

Heredity does much of the heavy lifting in forming individual temperament and personality differences, and peer influences do much of the rest. When with peers, teens discount the future and focus more on immediate rewards (O’Brien et al., 2011). Most teens are herd animals. They talk, dress, and act more like their peers than their parents. What their friends are, they often become, and what “everybody’s doing,” they often do. Teens’ social media use illustrates the power of peer influence. Compared to photos with few likes, teens prefer photos with many other likes—even photos of risky behaviors such as marijuana smoking. Moreover, when viewing many-liked photos, teens’ brains become more active in areas associated with reward processing and imitation (Sherman et al., 2016). Liking and doing what everybody else likes and does feels good.

“It’s you who don’t understand me—I’ve been fifteen, but you have never been forty-eight.”

Part of what everybody’s doing is networking—a lot. U.S. teens typically send 30 text messages daily and average 145 Facebook friends (Lenhart, 2015). They tweet, post videos to Snapchat, and share pictures on Instagram. Online communication stimulates intimate self-disclosure—both for better (support groups) and for worse (online predators and extremist groups) (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008; Valkenburg & Peter, 2009; Wilson et al., 2012).

“I’m fourteen, Mom, I don’t do hugs.”

Both online and in real life, for those who feel excluded and bullied by their peers, the pain is acute. Most excluded “students suffer in silence. . . . A small number act out in violent ways against their classmates” (Aronson, 2001). The pain of exclusion also persists. In one large study, those who were bullied as children showed poorer physical health and greater psychological distress 40 years later (Takizawa et al., 2014).

So, for adolescents, peer approval matters. Yet in other ways, parental approval matters, too. Teens have seen their parents as influential in shaping their religious faith and in thinking about college and career choices (Emerging Trends, 1997). Most adolescents identify with their parents’ political views (Ojeda & Hatemi, 2015).

“First, I did things for my parents’ approval, then I did things for my parents’ disapproval, and now I don’t know why I do things.”