Carl Rogers’ Person-Centered Perspective

Fellow humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers agreed with much of Maslow’s thinking. Rogers’ person-centered perspective held that people are basically good and are endowed with self-actualizing tendencies. Unless thwarted by an environment that inhibits growth, each of us is like an acorn, primed for growth and fulfillment. Rogers (1980) believed that a growth-promoting social climate provides:

- Acceptance: When people are accepting, they offer unconditional positive regard, an attitude of grace that values us even knowing our failings. It is a profound relief to drop our pretenses, confess our worst feelings, and discover that we are still accepted. In a good marriage, a close family, or an intimate friendship, we are free to be spontaneous without fearing the loss of others’ esteem.

- Genuineness: When people are genuine, they are open with their own feelings, drop their facades, and are transparent and self-disclosing.

- Empathy: When people are empathic, they share and mirror other’s feelings and reflect their meanings. “Rarely do we listen with real understanding, true empathy,” said Rogers. “Yet listening, of this very special kind, is one of the most potent forces for change that I know.” (When others talk do you generally listen closely, or just await your turn to talk?)

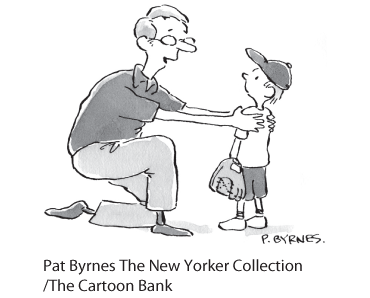

“Just remember, son, it doesn’t matter whether you win or lose—unless you want Daddy’s love.”

A father not offering unconditional positive regard:

So, some things get better with age: acceptance, genuineness, and empathy. These are, Rogers believed, the water, sun, and nutrients that enable people to grow like vigorous oak trees. For “as persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude toward themselves” (Rogers, 1980, p. 116). As persons are empathically heard, “it becomes possible for them to listen more accurately to the flow of inner experiencings.”

The picture of empathy Being open and sharing confidences is easier when the listener shows real understanding. Within such relationships we can relax and fully express our true selves. Consider a conversation when you knew someone was waiting for their turn to speak instead of listening to you. Now consider the last time someone heard you with empathy. How did those two experiences differ?

Writer Calvin Trillin (2006) recalled an example of parental acceptance and genuineness at a camp for children with severe disorders, where his wife, Alice, worked. L., a “magical child,” had genetic diseases that meant she had to be tube-fed and could walk only with difficulty. Alice recalled,

One day, when we were playing duck-duck-goose, I was sitting behind her and she asked me to hold her mail for her while she took her turn to be chased around the circle. It took her a while to make the circuit, and I had time to see that on top of the pile [of mail] was a note from her mom. Then I did something truly awful. . . . I simply had to know what this child’s parents could have done to make her so spectacular, to make her the most optimistic, most enthusiastic, most hopeful human being I had ever encountered. I snuck a quick look at the note, and my eyes fell on this sentence: “If God had given us all of the children in the world to choose from, L., we would only have chosen you.” Before L. got back to her place in the circle, I showed the note to Bud, who was sitting next to me. “Quick. Read this,” I whispered. “It’s the secret of life.”

Maslow and Rogers would have smiled knowingly. For them, a central feature of personality is one’s self-concept—all the thoughts and feelings we have in response to the question, “Who am I?” If our self-concept is positive, we tend to act and perceive the world positively. If it is negative—if in our own eyes we fall far short of our ideal self—said Rogers, we feel dissatisfied and unhappy. A worthwhile goal for therapists, parents, teachers, and friends is therefore, he said, to help others know, accept, and be true to themselves.