The Big Five Factors

Today’s trait researchers believe that simple trait factors, such as the Eysencks’ introversion–extraversion and stability–instability dimensions, are important, but they do not tell the whole story. A slightly expanded set of factors developed by Robert McCrae and Paul Costa—dubbed the Big Five—does a better job (Costa & McCrae, 2011). If a test specifies where you are on the five dimensions (conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion; see Table 57.1), it has said much of what there is to say about your personality.

| (Memory tip: Picturing a CANOE will help you recall these.) | ||

| Disorganized, careless, impulsive |  |

Organized, careful, disciplined |

| Ruthless, suspicious, uncooperative |  |

Soft-hearted, trusting, helpful |

| Calm, secure, self-satisfied |  |

Anxious, insecure, self-pitying |

| Practical, prefers routine, conforming |  |

Imaginative, prefers variety, independent |

| Retiring, sober, reserved |  |

Sociable, fun-loving, affectionate |

Source: Information from McCrae & Costa (1986, 2008).

Around the world—across 56 nations and 29 languages in one study (Schmitt et al., 2007)—people describe others in terms roughly consistent with this list. The Big Five—today’s “common currency for personality psychology” (Funder, 2001)—has been the most active personality research topic since the early 1990s and is currently our best approximation of the basic trait dimensions.

Big Five research has explored various questions:

- How stable are these traits? One research team analyzed 1.25 million participants ages 10 to 65. They learned that personality continues to develop and change through late childhood and adolescence. Up to age 40, we show signs of a maturity principle: We become more conscientious and agreeable and less neurotic (emotionally unstable) (Bleidorn, 2015; Milojev & Sibley, 2016). Great apes show similar personality maturation (Weiss & King, 2015). After age 40, our traits further stabilize.

- How heritable are these traits? Heritability (the extent to which individual differences are attributable to genes) generally runs about 40 percent for each dimension (Vukasovi´c & Bratko, 2015). Many genes, each having small effects, combine to influence our traits (McCrae et al., 2010; van den Berg et al., 2016).

- Do these traits reflect differing brain structure? The size and thickness of brain tissue correlates with several Big Five traits (DeYoung et al., 2010; Grodin & White, 2015; Riccelli et al., 2017). For example, those who score high on conscientiousness tend to have a larger frontal lobe area that aids in planning and controlling behavior. Brain connections also influence the Big Five traits (Adelstein et al., 2011). People high in neuroticism (emotional instability) have brains that are wired to experience stress intensely (Shackman et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2012).

- Do these traits reflect birth order? After controlling for other variables such as family size, are first-born children, for example, more conscientious and agreeable? Contrary to popular opinion, several massive studies failed to find any association between birth order and personality (Damian & Roberts, 2015; Harris, 2009; Rohrer et al., 2015).

- How well do these traits apply to various cultures? The Big Five dimensions describe personality in various cultures reasonably well (Fetvadjiev et al., 2017; Schmitt et al., 2007; Vazsonyi et al., 2015). After studying people from 50 cultures, Robert McCrae and 79 co-researchers concluded that “features of personality traits are common to all human groups” (2005).

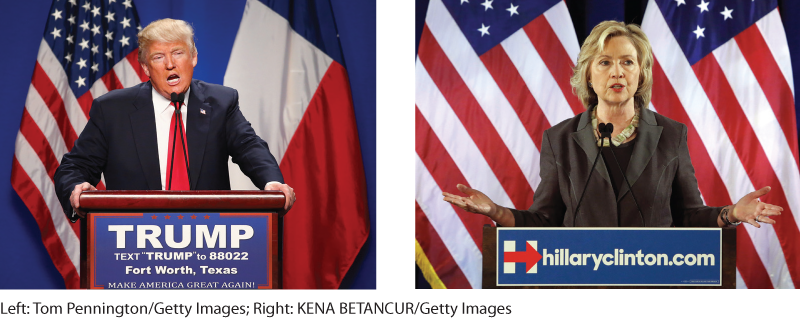

- Do the Big Five traits predict our actual behaviors? Yes. If people report being outgoing, conscientious, and agreeable, “they probably are telling the truth,” reports McCrae (2011). Conscientiousness and agreeableness predict workplace success, and agreeableness predicts helpfulness (Habashi et al., 2016; Sackett & Walmsley, 2014). Traits also characterize certain career paths. For example, U.S. politicians often have “big” personalities, outscoring the general public on extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability (low neuroticism) (Hanania, 2017). Our traits also appear in our language patterns. In text messaging, extraversion predicts use of personal pronouns. Neuroticism predicts negative-emotion words (Holtgraves, 2011).

How do you vote? Let me count the likes. Researchers can use your Facebook likes to predict your Big Five traits, your opinions, and your political attitudes (Youyou et al., 2015). Companies gather these “big data” for advertisers (who then personalize the ads you see). They do the same for political candidates, who can target you with persuasive messages. In the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, “both sides were certainly using big data . . . to win over voters,” says researcher Michal Kosinski (Zakaria, 2017).

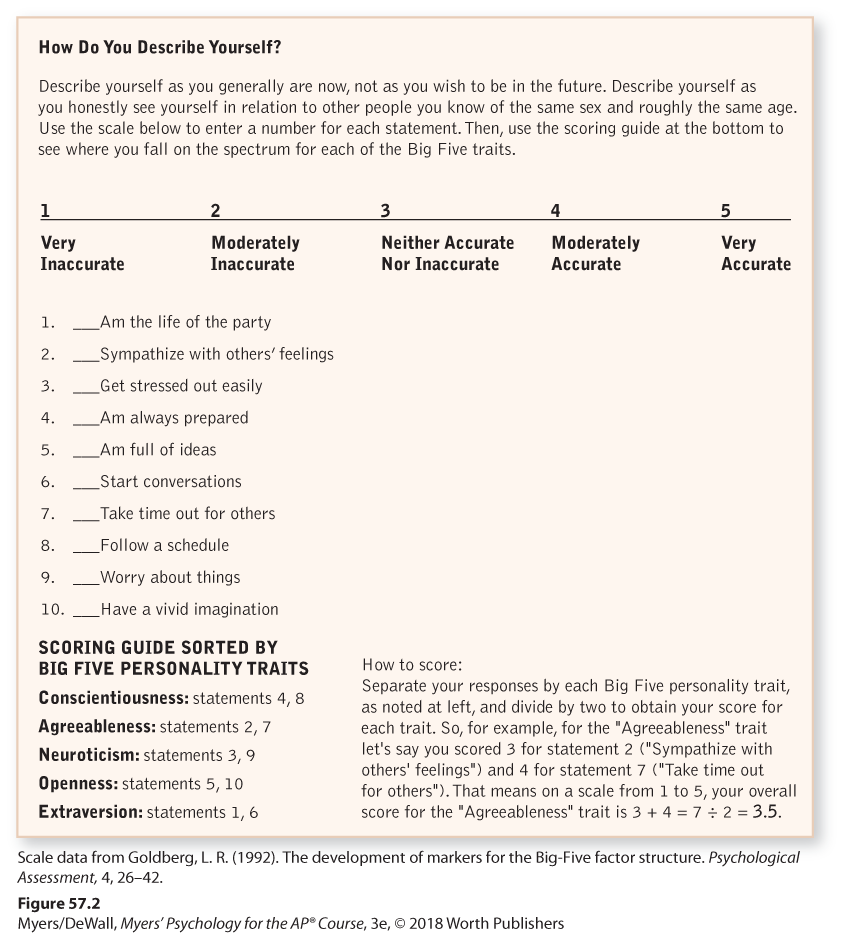

By exploring such questions, Big Five research has sustained trait psychology and renewed appreciation for the importance of personality. (To describe your personality, try the brief self-assessment in Figure 57.2.) Traits matter. In the next section, we will see that situations matter, too.

Figure 57.2 The Big Five self-assessment