Rates of Psychological Disorders

Who is most vulnerable to psychological disorders? At what times of life? To answer such questions, many countries have conducted lengthy structured interviews with representative samples of thousands of their citizens. After asking hundreds of questions that probed for symptoms—“Has there ever been a period of two weeks or more when you felt like you wanted to die?”—the researchers have estimated the current, prior-year, and lifetime prevalence of various disorders.

How many people have, or have had, a psychological disorder? More than most of us suppose:

- The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (2015) has estimated that just under 1 in 5 adult Americans currently have a “mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder (excluding developmental and substance use disorders)” or have had one within the past year (Table 65.2).

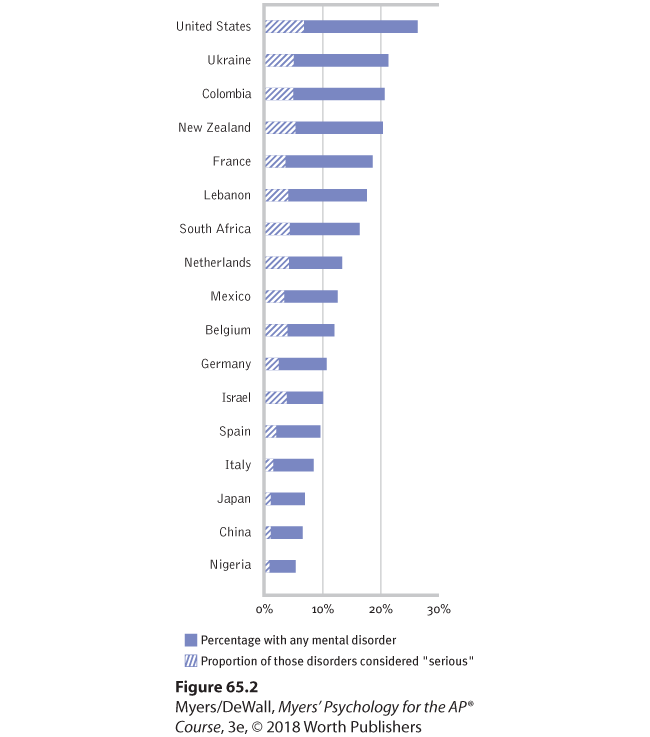

- A World Health Organization study—based on 90-minute interviews with thousands of people who were representative of their country’s population—estimated the number of prior-year mental disorders in 28 countries (Kessler et al., 2009). As Figure 65.2 illustrates, the lowest rate of reported mental disorders was in Nigeria, the highest rate in the United States. Moreover, immigrants to the United States from Mexico, Africa, and Asia averaged better mental health than their U.S. counterparts with the same ethnic heritage (Breslau et al., 2007; Maldonado-Molina et al., 2011). For example, compared with Mexican-Americans born in the United States, Mexican-Americans who have recently immigrated are less at risk for mental disorders—a phenomenon known as the immigrant paradox (Schwartz et al., 2010).

| Psychological Disorder | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Depressive disorders or bipolar disorder | 9.3 |

| Phobia of specific object or situation | 8.7 |

| Social anxiety disorder | 6.8 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | 4.1 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 3.5 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.1 |

| Schizophrenia | 1.1 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 1.0 |

Data from: National Institute of Mental Health, 2015.

Figure 65.2 Prior-year prevalence of disorders in selected areas

From interviews in 28 countries (Kessler et al., 2009).

What increases vulnerability to mental disorders? As Table 65.3 indicates, there is a wide range of risk and protective factors for mental disorders. But one predictor of mental disorder—poverty—crosses ethnic and gender lines. The incidence of serious psychological disorders is 2.5 times higher among those below the poverty line (CDC, 2014). Like so many other correlations, the poverty-disorder association raises further questions: Does poverty cause disorders? Or do disorders cause poverty? It is both, though the answer varies with the disorder. Schizophrenia understandably leads to poverty. Yet the stresses and demoralization of poverty can also precipitate disorders, especially depression in women and substance abuse in men (Dohrenwend et al., 1992). In one natural experiment investigating the poverty-pathology link, researchers tracked rates of behavior problems in North Carolina Native American children as economic development enabled a dramatic reduction in their community’s poverty rate. As the study began, children of poverty exhibited more deviant and aggressive behaviors. After four years, children whose families had moved above the poverty line exhibited a 40 percent decrease in behavior problems. Those who maintained their previous positions below or above the poverty line exhibited no change (Costello et al., 2003).

| Risk Factors | Protective Factors |

|---|---|

| Academic failure

Birth complications Caring for those who are chronically ill or who have a neurocognitive disorder Child abuse and neglect Chronic insomnia Chronic pain Family disorganization or conflict Low birth weight Low socioeconomic status Medical illness Neurochemical imbalance Parental mental illness Parental substance abuse Personal loss and bereavement Poor work skills and habits Reading disabilities Sensory disabilities Social incompetence Stressful life events Substance abuse Trauma experiences |

Aerobic exercise

Community offering empowerment, opportunity, and security Economic independence Effective parenting Feelings of mastery and control Feelings of security High self-esteem Literacy Positive attachment and early bonding Positive parent-child relationships Problem-solving skills Resilient coping with stress and adversity Social and work skills Social support from family and friends |

Research from: World Health Organization (WHO, 2004b,c).

At what times of life do disorders strike? Usually by early adulthood. “Over 75 percent of our sample with any disorder had experienced [their] first symptoms by age 24,” reported Lee Robins and Darrel Regier (1991, p. 331). Among the earliest to appear are the symptoms of antisocial personality disorder (median age 8) and of phobias (median age 10). Alcohol use disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia symptoms appear at a median age near 20. Major depressive disorder often hits somewhat later, at a median age of 25.