Bipolar Disorder

Our genes dispose some of us, more than others, to respond emotionally to good and bad events (Whisman et al., 2014). In bipolar disorder, people bounce from one emotional extreme to the other (week to week, rather than day to day or moment to moment). When a depressive episode ends, a euphoric, overly talkative, wildly energetic, and extremely optimistic state called mania follows. But before long, the mood either returns to normal or plunges again into depression.

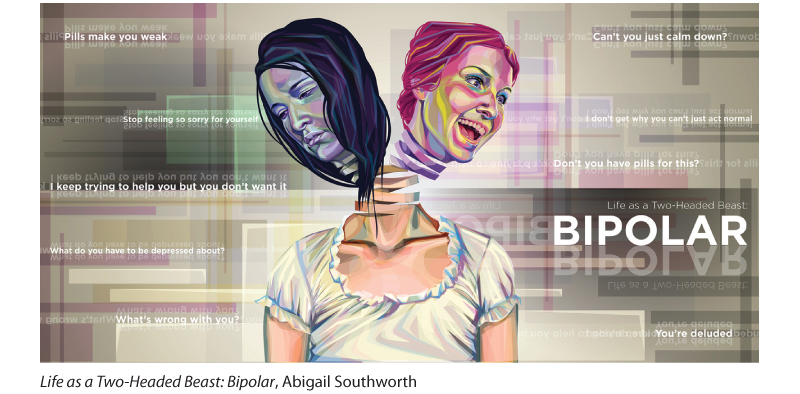

Bipolar disorder Artist Abigail Southworth illustrated her experience of bipolar disorder.

During the manic phase, people with bipolar disorder typically have little need for sleep. They show fewer sexual inhibitions. Their positive emotions persist abnormally (Gruber, 2011; Gruber et al., 2013). Their speech is loud, flighty, and hard to interrupt. They find advice irritating. Yet they need protection from their own poor judgment, which may lead to reckless spending or unsafe sex. Thinking fast feels good, but it also increases risk taking (Chandler & Pronin, 2012; Pronin, 2013).

In milder forms, mania’s energy and flood of ideas can fuel creativity. Clusters of genes associated with high creativity increase the likelihood of having bipolar disorder, and risk factors for developing bipolar disorder predict greater creativity (Baas et al., 2016; Power et al., 2015). George Frideric Handel, who may have suffered from a mild form of bipolar disorder, composed his nearly four-hour-long Messiah (1742) during three weeks of intense creative energy (Keynes, 1980). Robert Schumann composed 51 musical works during two years of mania (1840 and 1849) but none during 1844, when he was severely depressed (Slater & Meyer, 1959). Those who rely on precision and logic, such as architects, designers, and journalists, suffer bipolar disorder less often than do those who rely on emotional expression and vivid imagery (Ludwig, 1995). Composers, artists, poets, novelists, and entertainers seem especially prone (Jamison, 1993, 1995; Kaufman & Baer, 2002; Ludwig, 1995). Indeed, one analysis of over a million individuals showed that the only psychiatric condition linked to working in a creative profession was bipolar disorder (Kyaga et al., 2013).

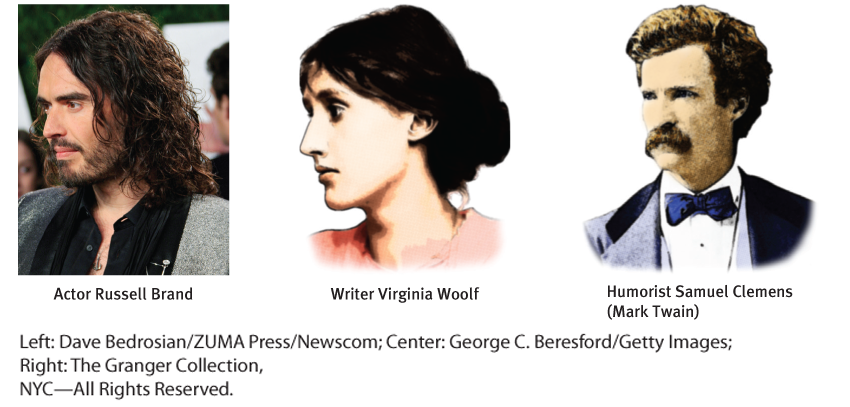

Creativity and bipolar disorder There have been many creative artists, composers, writers, and musical performers with bipolar disorder.

Though bipolar disorder is much less common than major depressive disorder, it is often more dysfunctional, claiming twice as many lost workdays yearly (Kessler et al., 2006). It is also a potent predictor of suicide (Schaffer et al., 2015). Unlike major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder afflicts as many men as women. The diagnosis has risen among adolescents, whose mood swings, sometimes prolonged, may vary from raging to bubbly. In the decade between 1994 and 2003, bipolar diagnoses in Americans under the age of 20 revealed an astonishing 40-fold increase—from an estimated 20,000 to 800,000 (Carey, 2007; Flora & Bobby, 2008; Moreno et al., 2007). Americans are twice as likely as people of other countries to have ever had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Merikangas et al., 2011). The new DSM-5 classifications have, however, begun to reduce the number of child and adolescent bipolar diagnoses: Some of those who are persistently irritable and who have frequent and recurring behavior outbursts are now instead diagnosed with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (Faheem et al., 2017).