Dissociative Disorders

Among the most bewildering disorders are the rare dissociative disorders, in which a person’s conscious awareness dissociates (separates) from painful memories, thoughts, and feelings. The result may be a fugue state, a sudden loss of memory or change in identity, often in response to an overwhelmingly stressful situation. (Note that this explanation presumes the existence of repressed memories, which, as we noted in Modules 33 and 56, memory researchers have questioned.) Such was the case for one Vietnam veteran who was haunted by his comrades’ deaths, and who had left his World Trade Center office shortly before the 9/11 terrorist attack. Later, he disappeared. Six months later, when he was discovered in a Chicago homeless shelter, he reported no memory of his identity or family (Stone, 2006).

Dissociation itself is not so rare. Any one of us may have a sense of being unreal, of being separated from our body, of watching ourselves as if in a movie. Sometimes we may say, “I was not myself at the time.” Perhaps you can recall getting up to go somewhere and ending up at some unintended location while your mind was preoccupied. Or perhaps you can play a well-practiced tune on a guitar or piano while talking to someone. When we face trauma, dissociative detachment may protect us from being overwhelmed by emotion.

Dissociative Identity Disorder

A massive dissociation of self from ordinary consciousness occurs in dissociative identity disorder (DID—formerly called multiple personality disorder), in which two or more distinct identities—each with its own voice and mannerisms—seem to control a person’s behavior at different times. Thus, the person may be prim and proper one moment, loud and flirtatious the next. Typically, the original personality denies any awareness of the other(s).

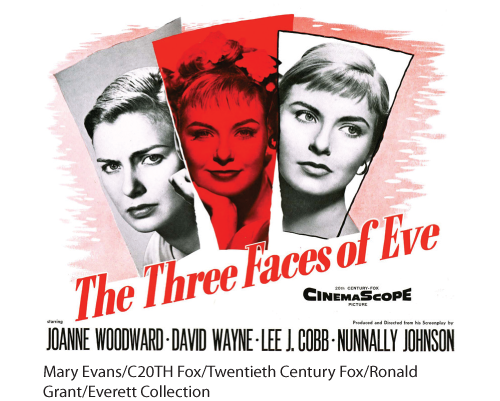

Multiple personalities Chris Sizemore’s story, told in the book and movie The Three Faces of Eve, gave early visibility to what is now called dissociative identity disorder.

People diagnosed with DID are rarely violent. But cases have been reported of dissociations into a “good” and a “bad” (or aggressive) personality—a modest version of the Dr. Jekyll–Mr. Hyde split immortalized in Robert Louis Stevenson’s story. One unusual case involved Kenneth Bianchi, accused in the “Hillside Strangler” rapes and murders of 10 California women. During a hypnosis session, Bianchi’s psychologist “called forth” a hidden personality: “I’ve talked a bit to Ken, but I think that perhaps there might be another part of Ken that . . . maybe feels somewhat differently from the part that I’ve talked to. . . . Would you talk with me, Part, by saying, ‘I’m here’?” Bianchi answered “Yes” and then claimed to be “Steve” (Watkins, 1984).

Speaking as Steve, Bianchi stated that he hated Ken because Ken was nice and that he (Steve), aided by a cousin, had murdered women. He also claimed Ken knew nothing about Steve’s existence and was innocent of the murders. Was Bianchi’s second personality a trick, simply a way of disavowing responsibility for his actions? Indeed, Bianchi—a practiced liar who had read about multiple personality in psychology books—was later convicted.

Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder

Skeptics question DID. First, instead of being a true disorder, could DID be an extension of our normal capacity for personality shifts? Nicholas Spanos (1986, 1994, 1996) asked college students to pretend they were accused murderers being examined by a psychiatrist. Given the same hypnotic treatment Bianchi received, most spontaneously expressed a second personality. This discovery made Spanos wonder: Perhaps dissociative identities are simply a more extreme version of the varied “selves” we normally present—as when we display a goofy, loud self while hanging out with friends, and a subdued, respectful self around grandparents. Are clinicians who discover multiple personalities merely triggering role playing by fantasy-prone people? Do these people, like actors who commonly report “losing themselves” in their roles, then convince themselves of the authenticity of their own role enactments? Spanos was no stranger to this line of thinking. In a related research area, he had also raised these questions about the hypnotic state. Because most DID patients are highly hypnotizable, whatever explains one condition—dissociation or role playing—may help explain the other.

“ Pretense may become reality.”

Chinese proverb

Skeptics also find it suspicious that the disorder has such a short and localized history. Between 1930 and 1960, the number of North American DID diagnoses averaged 2 per decade. By the 1980s, when the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) contained the first formal code for this disorder, the number had exploded to more than 20,000 (McHugh, 1995a). The average number of displayed personalities also mushroomed—from 3 to 12 per patient (Goff & Simms, 1993). Although diagnoses are increasing in countries where DID has been publicized, the disorder is much less prevalent outside North America (Lilienfeld, 2017). In Britain, diagnosis of DID—which some have considered “a wacky American fad” (Cohen, 1995)—has been rare.

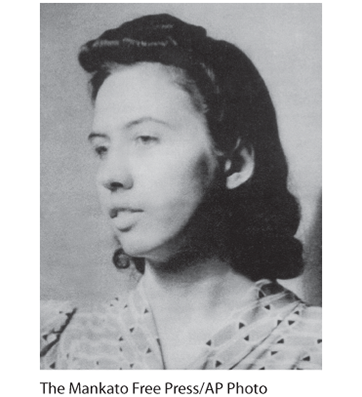

Widespread dissociation Shirley Mason was a psychiatric patient diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder. Her life formed the basis of the bestselling book Sybil (Schreiber, 1973) and of two movies. Some argue that the book and movies’ popularity fueled the dramatic rise in diagnoses of DID. Skeptics wonder whether Mason actually had the disorder (Nathan, 2011).

Such findings, skeptics have noted, point to a disorder of suggestible, fantasy-prone people created by therapists in a particular social context (Giesbrecht et al., 2008, 2010; Lynn et al., 2014; Merskey, 1992). Clients do not enter therapy saying “Allow me to introduce myselves.” Instead, charge the critics, some therapists go fishing for multiple personalities: “Have you ever felt like another part of you does things you can’t control? Does this part of you have a name? Can I talk to the angry part of you?” Once clients permit a therapist to talk, by name, “to the part of you that says those angry things,” they begin acting out the fantasy. The result may be the experience of another self.

Other researchers and clinicians believe DID is a real disorder. They cite findings of distinct body and brain states associated with differing personalities (Putnam, 1991). Abnormal brain anatomy and activity can also accompany DID. Brain scans show shrinkage in areas that aid memory and detection of threat (Vermetten et al., 2006). Heightened activity appears in brain areas associated with the control and inhibition of traumatic memories (Elzinga et al., 2007).

Both the psychodynamic and learning perspectives have interpreted DID symptoms as ways of coping with anxiety. Some psychodynamic theorists see them as defenses against the anxiety caused by the eruption of unacceptable impulses. In this view, a second personality enables the discharge of forbidden impulses. Learning theorists see dissociative disorders as behaviors reinforced by anxiety reduction.

“ Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.”

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1600

Some clinicians include dissociative disorders under the umbrella of posttraumatic stress disorder—a natural, protective response to traumatic experiences during childhood (Brand et al., 2016; Spiegel, 2008). Many people being treated for DID recall being physically, sexually, or emotionally abused as children (Gleaves, 1996; Lilienfeld et al., 1999). In one study of 12 murderers diagnosed with DID, 11 had suffered severe, torturous child abuse (Lewis et al., 1997). One had been set afire by his parents. Another had been used in child pornography and was scarred from being made to sit on a stove burner. Some critics wonder, however, whether vivid imagination or therapist suggestion contributed to such recollections (Kihlstrom, 2005).

“Would it be possible to speak with the personality that pays the bills?”

So the debate continues. On one side are those who believe multiple personalities are the desperate efforts of people trying to detach from a horrific existence. On the other are skeptics who think DID is constructed out of the therapist-client interaction and acted out by fantasy-prone, emotionally vulnerable people. If the skeptics’ view wins, predicted psychiatrist Paul McHugh (1995b), “this epidemic will end in the way that the witch craze ended in Salem. The [multiple personality phenomenon] will be seen as manufactured.”