Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Therapies

The first major psychological therapy was Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. Although few clinicians today practice therapy as Freud did, his work deserves discussion. It helped form the foundation for treating psychological disorders, and it continues to influence modern therapists working from the psychodynamic perspective.

The Goals of Psychoanalysis

Freud believed that in therapy, people could achieve healthier, less anxious living by releasing the energy they had previously devoted to id-ego-superego conflicts (see Module 55). Freud assumed that we do not fully know ourselves. He believed that there are threatening things we repress—things we do not want to know, so we disavow or deny them. Psychoanalysis was Freud’s method of helping people to bring these repressed feelings into conscious awareness. By helping them reclaim their unconscious thoughts and feelings, and by giving them insight into the origins of their disorders, the therapist (analyst) could help them reduce growth-impeding inner conflicts.

The Techniques of Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalytic theory emphasizes the power of childhood experiences to mold the adult. Thus, psychoanalysis is historical reconstruction. It aims to unearth the past in the hope of loosening its bonds on the present. After discarding hypnosis as an unreliable excavator, Freud turned to free association.

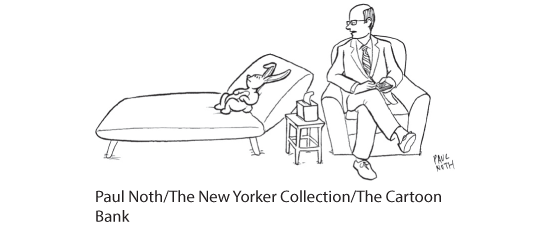

Imagine yourself as a patient using free association. You begin by relaxing, perhaps by lying on a couch. The psychoanalyst, who sits out of your line of vision, asks you to say aloud whatever comes to mind. At one moment, you’re relating a childhood memory. At another, you’re describing a dream or recent experience. It sounds easy, but soon you notice how often you edit your thoughts as you speak. You pause for a second before uttering an embarrassing thought. You omit what seems trivial, irrelevant, or shameful. Sometimes your mind goes blank or you clutch up, unable to remember important details. You may joke or change the subject to something less threatening.

To the analyst, these mental blocks indicate resistance. They hint that anxiety lurks and you are defending against sensitive material. The analyst will note your resistance and then provide insight into its meaning. If offered at the right moment, this interpretation—of, say, your not wanting to talk about your mother or call, text, or message her—may illuminate the underlying wishes, feelings, and conflicts you are avoiding. The analyst may also offer an explanation of how this resistance fits with other pieces of your psychological puzzle, including those based on analysis of your dream content.

Over many such sessions, your relationship patterns surface in your interaction with your therapist. You may find yourself experiencing strong positive or negative feelings for your analyst. The analyst may suggest you are transferring feelings, such as dependency or mingled love and anger, that you experienced in earlier relationships with family members or other important people. By exposing such feelings, you may gain insight into your current relationships.

Relatively few North American therapists now offer traditional psychoanalysis. Much of its underlying theory is not supported by scientific research (Module 56). Analysts’ interpretations cannot be proven or disproven. And psychoanalysis takes considerable time and money, often years of several sessions per week. Some of these problems have been addressed in the modern psychodynamic perspective that has evolved from psychoanalysis.

“ I haven’t seen my analyst in 200 years. He was a strict Freudian. If I’d been going all this time, I’d probably almost be cured by now.”

Woody Allen, after awakening from suspended animation in the movie Sleeper

Psychodynamic Therapy

Although influenced by Freud’s ideas, psychodynamic therapists don’t talk much about id-ego-superego conflicts. Instead they try to help people understand their current symptoms by focusing on important relationships, including childhood experiences and the therapist-client relationship. “We can have loving feelings and hateful feelings toward the same person,” noted psychodynamic therapist Jonathan Shedler (2009), and “we can desire something and also fear it.” Client-therapist meetings take place once or twice a week (rather than several times weekly) and often for only a few weeks or months. Rather than lying on a couch, out of the therapist’s line of vision, clients meet with their therapist face-to-face and gain perspective by exploring defended-against thoughts and feelings.

“I’m more interested in hearing about the eggs you’re hiding from yourself.”

Therapist David Shapiro (1999, p. 8) illustrated this with the case of a young man who had told women that he loved them, when he knew that he didn’t. The client’s explanation: They expected it, so he said it. But with his wife, who wished he would say that he loved her, he found he couldn’t do that—“I don’t know why, but I can’t.”

Therapist: Do you mean, then, that if you could, you would like to?

Patient: Well, I don’t know. . . . Maybe I can’t say it because I’m not sure it’s true. Maybe I don’t love her.

Further interactions revealed that the client could not express real love because it would feel “mushy” and “soft” and therefore unmanly. He was “in conflict with himself, and . . . cut off from the nature of that conflict.” Shapiro noted that with such patients, who are estranged from themselves, therapists using psychodynamic techniques “are in a position to introduce them to themselves. We can restore their awareness of their own wishes and feelings, and their awareness, as well, of their reactions against those wishes and feelings.”

Exploring past relationship troubles may help clients understand the origin of their current difficulties. Shedler (2010a) recalled “Jeffrey’s” complaints of difficulty getting along with his colleagues and wife, who saw him as hypercritical. Jeffrey then “began responding to me as if I were an unpredictable, angry adversary.” Shedler seized this opportunity to help Jeffrey recognize the relationship pattern and its roots in the attacks and humiliation he had experienced from his alcohol-abusing father. Jeffrey was then able to work through and let go of this defensive style of responding to people. Thus, without embracing all of Freud’s theory, psychodynamic therapists aim to help people gain insight into unconscious dynamics that arise from their life experience.