Cultural Influences

Compared with the narrow path taken by flies, fish, and foxes, the road along which environment drives us is wider. The mark of our species—nature’s great gift to us—is our ability to learn and adapt. We come equipped with a huge cerebral hard drive ready to receive cultural software.

Culture is the behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next (Brislin, 1988; Cohen, 2009). Human nature, noted Roy Baumeister (2005), seems designed for culture. We are social animals, but more. Wolves are social animals; they live and hunt in packs. Ants are incessantly social, never alone. But “culture is a better way of being social,” observed Baumeister. Wolves function pretty much as they did 10,000 years ago. We enjoy countless things that were unknown to our century-ago ancestors. Culture works.

Other animals exhibit smaller kernels of culture. Chimpanzees sometimes invent customs—using leaves to clean their bodies, slapping branches to get attention, and doing a “rain dance” by slowly displaying themselves at the start of rain—and pass them on to their peers and offspring (Whiten et al., 1999). Culture supports survival and reproduction by transmitting learned behaviors that give a group an edge. But human culture does more.

Thanks to our culture’s mastery of language, we humans enjoy the preservation of innovation. Within the span of this day, we have used Google, smart phones, digital hearing technology [DM], and a GPS running watch [ND]. On a grander scale, we have culture’s accumulated knowledge to thank for the last century’s 30-year extension of the average human life expectancy in many countries. Moreover, culture enables an efficient division of labor. Although two lucky people get their name on this book (which transmits accumulated cultural wisdom), the product actually results from the coordination and commitment of a team of gifted people, no one of whom could produce it alone.

Across cultures, we differ. But beneath differences is our great similarity—our capacity for culture. Culture transmits the customs and beliefs that enable us to communicate, to exchange money for things, to play, to eat, and to drive with agreed-upon rules and without crashing into one another.

Variation Across Cultures

We see our adaptability in cultural variations among our beliefs and our values, in how we nurture our children and bury our dead, and in what we wear (or whether we wear anything at all). We are ever mindful that the worldwide readers of this book are culturally diverse. You and your ancestors reach from Asia to Africa.

Riding along with a unified culture is like biking with the wind: As it carries us along, we hardly notice it is there. When we try biking against the wind we feel its force. Face-to-face with a different culture, we become aware of the cultural winds. Visiting Europe, most North Americans notice the smaller cars, the left-handed use of the fork, the uninhibited attire on the beaches. Stationed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Kuwait, American and European soldiers alike realized how liberal their home cultures were. Arriving in North America, visitors from Japan and India struggle to understand why so many people wear their dirty street shoes in the house.

But humans in varied cultures nevertheless share some basic moral ideas. Even before they can walk, babies prefer helpful people over naughty ones (Hamlin et al., 2011). Worldwide, people prize honesty, fairness, and kindness (McGrath, 2015). Yet each cultural group also evolves its own norms. The British have a norm for orderly waiting in line. Many South Asians use only the right hand for eating. Sometimes social expectations seem oppressive: “Why should it matter how I dress?” Yet, norms—how to greet, how to eat—grease the social machinery.

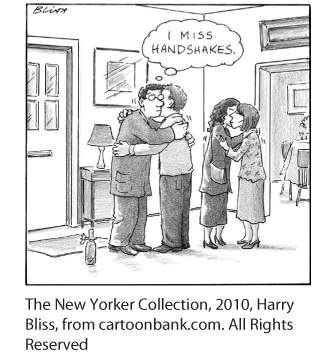

When cultures collide, their differing norms often befuddle. Should we greet people by shaking hands, bowing, or kissing each cheek? Knowing what sorts of gestures and compliments are culturally appropriate, we can relax and enjoy one another without fear of embarrassment or insult.

When we don’t understand what’s expected or accepted, we may experience culture shock. People from Mediterranean cultures have perceived northern Europeans as efficient but cold and preoccupied with punctuality (Triandis, 1981). People from time-conscious Japan—where bank clocks keep exact time, pedestrians walk briskly, and postal clerks fill requests speedily—have found themselves growing impatient when visiting Indonesia, where the pace of life is more leisurely (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999). Someone from the European community, which requires 20 paid vacation days each year, may also experience culture shock when working in the United States, which does not guarantee workers any paid vacation (Ray et al., 2013).

Variation Over Time

Like biological creatures, cultures vary and compete for resources, and thus evolve over time (Mesoudi, 2009). Consider how rapidly cultures may change. English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (1342–1400) is separated from a modern Briton by only 25 generations, but the two would have great difficulty communicating. At the beginning of the last century, your ancestors lived in a world without cars, radio broadcasting, or widespread electric power and light. In the thin slice of history since 1960, most Western cultures have changed with astonishing speed. Middle-class people enjoy the convenience of air-conditioned housing, online shopping, anywhere-anytime electronic communication, and—enriched by doubled per-person real income—eating out more than twice as often as did their grandparents back in the culture of 1960. Many people now enjoy expanded human rights. And with greater economic independence, today’s women more often marry for love and less often endure abusive relationships.

But some changes seem not so wonderfully positive. Had you fallen asleep in the United States in 1960 and awakened today, you would open your eyes to a culture with more depression and more economic inequality. You would also find North Americans—like their counterparts in Britain, Australia, and New Zealand—spending more hours at work, fewer hours with friends and family, and fewer hours asleep (BLS, 2011; Putnam, 2000).

Whether we love or loathe these changes, we cannot fail to be impressed by their breathtaking speed. And we cannot explain them by changes in the human gene pool, which evolves far too slowly to account for high-speed cultural transformations. Cultures vary. Cultures change. And cultures shape our lives.