Targets of Prejudice

Racial and Ethnic Prejudice

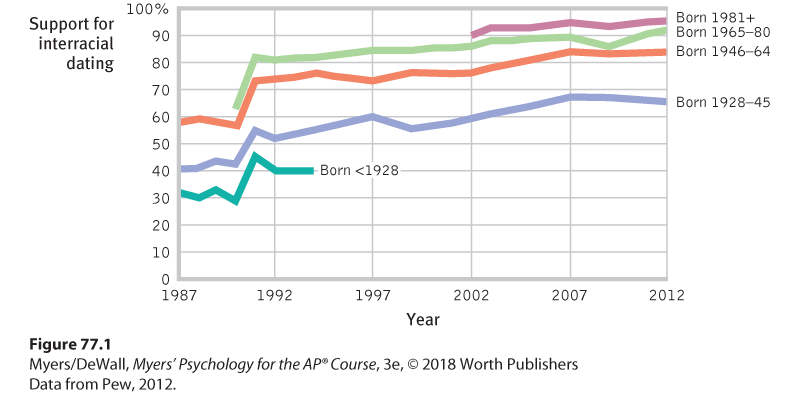

Americans’ expressed racial attitudes have changed dramatically in the last half-century. Support for interracial dating between Blacks and Whites, for example, has increased dramatically, from a 48 percent approval rate in 1987 to 86 percent in 2012 (Pew, 2012; see also Figure 77.1). Similarly, 4 percent of Americans approved of “marriage between Blacks and Whites” in 1958, but 87 percent approved in 2013 (Newport, 2013). Six in ten Americans—double the number in most European countries—agree that “an increasing number of people of many different races, ethnic groups, and nationalities in our country makes it a better place to live” (Drake & Poushter, 2016).

Figure 77.1 Prejudice over time

Over the last quarter-century, Americans have increasingly approved of interracial dating, with each successive generation expressing more approval.

Yet as blatant interracial prejudice wanes, subtle prejudice lingers. People with darker skin tones experience greater criticism and accusations of immoral behavior (Alter et al., 2016). In one study of White medical students and residents, 1 in 3 believed “black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s skin,” which led them to make harmful treatment recommendations (Hoffman et al., 2016). And although many people say they would feel upset with someone making racist or homophobic slurs, they respond indifferently when they actually hear prejudice-laden language (Kawakami et al., 2009).

“ Unhappily, the world has yet to learn how to live with diversity.”

Pope John Paul II, Address to the United Nations, 1995

Other studies reveal prejudice that is not just subtle, but unconscious (implicit). For example, in an Implicit Association Test, 9 in 10 White respondents took longer to identify pleasant words (such as peace and paradise) as “good” when presented with Black-sounding names (such as Latisha and Darnell) rather than with White-sounding names (such as Katie and Ian). Moreover, people who more quickly associate good things with White names or faces also are the quickest to perceive anger and apparent threat in Black faces (Hugenberg & Bodenhausen, 2003). A greater association of pleasant words with the racial terms “White” than “Black” has also been observed in more than 800 billion Internet words (Caliskan et al., 2017). In the 2008 U.S. presidential election, those demonstrating explicit or implicit prejudice were less likely to vote for candidate Barack Obama. His election in turn served to reduce implicit prejudice (Bernstein et al., 2010; Payne et al., 2010; Stephens-Davidowitz, 2014).

“ If we can’t help our latent biases, we can help our behavior in response to those instinctive reactions, which is why we work to design systems and processes that overcome that very human part of us all.”

U.S. FBI Director James B. Comey, “Hard Truths: Law Enforcement and Race,” 2015

Our perceptions can also reflect implicit bias. In 1999, Amadou Diallo was accosted as he approached his apartment house doorway by police officers looking for a rapist. When he pulled out his wallet, the officers, perceiving a gun, riddled his body with 19 bullets from 41 shots. In one analysis of 59 unarmed suspect shootings in Philadelphia over seven years, 49 involved the misidentification of an object (such as a cell phone) or movement (such as pants tugging). Black suspects were more than twice as likely to be misperceived as threatening, even by Black officers (Blow, 2015). During 2015–2016, African Americans, who are 13 percent of the U.S. population, were nearly 40 percent of the unarmed people shot and killed by police (Washington Post, 2017).

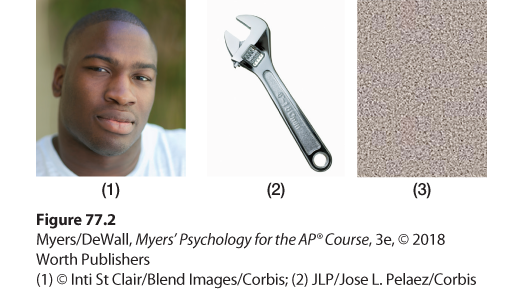

To better understand such tragic shootings of unarmed, innocent people, two research teams simulated the situation (Correll et al., 2007, 2015; Plant & Peruche, 2005; Sadler et al., 2012). They asked viewers to press buttons quickly to “shoot” or not shoot men who suddenly appeared on screen. Some of the onscreen men held a gun. Others held a harmless object, such as a flashlight or bottle. People (both Blacks and Whites, and police officers) more often shot Black men holding the harmless object. Priming people with a flashed Black face rather than a White face also made them more likely to misperceive a flashed tool as a gun (Figure 77.2). Fatigue, which diminishes one’s conscious control and increases automatic reactions, amplifies racial bias in decisions to shoot (Ma et al., 2013).

Figure 77.2 Race primes perceptions

In experiments by Keith Payne (2006), people viewed (1) a White or Black face, immediately followed by (2) a flashed gun or hand tool, which was then followed by (3) a masking screen. Participants were more likely to misperceive a tool as a gun when it was preceded by a Black rather than White face.

Gender Prejudice

Overt gender prejudice has declined sharply. The one-third of Americans who in 1937 told Gallup pollsters that they would vote for a qualified woman whom their party nominated for president soared to 95 percent in 2012 (Jones, 2012; Newport, 1999). Although women worldwide still represent nearly two-thirds of illiterate adults, and 30 percent have experienced intimate partner violence, 65 percent of all people now say it is very important that women have the same rights as men (UN, 2015; WHO, 2016; Zainulbhai, 2016).

“ Until I was a man, I had no idea how good men had it at work. . . . The first time I spoke up in a meeting in my newly low, quiet voice and noticed that sudden, focused attention, I was so uncomfortable that I found myself unable to finish my sentence.”

Thomas Page McBee, 2016, after transitioning from female to male

Nevertheless, both implicit and explicit gender prejudice and discrimination persist. In Western countries, we pay more to those (usually men) who care for our streets than to those (usually women) who care for our children. Gender bias even applies to beliefs about intelligence: Despite equality between the sexes in intelligence scores, people have tended to perceive their fathers as more intelligent than their mothers and their sons as brighter than their daughters (Furnham, 2016).

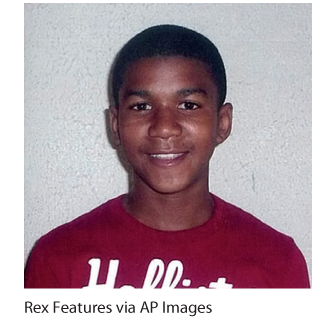

When tragedy triggers a national response Does implicit bias research—which is now being integrated into both police and corporate diversity training programs—help us understand the 2013 death of Trayvon Martin (shown here 7 months before he was killed)? As he walked alone to his father’s fiance’s house in a gated Florida neighborhood, a suspicious resident started following him. A confrontation led to the unarmed Martin being shot. Martin’s death sparked public outrage related to racism, gun control, and social justice. Commentators wondered: Had Martin been an unarmed White teen, would he have been perceived and treated the same way?

Unwanted female infants are no longer left out on a hillside to die of exposure, as was the practice in ancient Greece. Yet the normal male-to-female newborn ratio (105-to-100) hardly explains the world’s estimated 163 million (say that number slowly) “missing women” (Hvistendahl, 2011). In many places, sons are valued more than daughters. In India, there are 3.5 times more Google searches asking how to conceive a boy than how to conceive a girl (Stephens-Davidowitz, 2014). With scientific testing that enables sex-selective abortions, some countries are experiencing a shortfall in female births. India’s newborn sex ratio was recently 112 boys for every 100 girls. China’s has been 111 to 100—despite China’s declaring sex-selective abortions—gender genocide—a criminal offense (CIA, 2014). With under-age-20 males exceeding females by 32 million, many Chinese bachelors will be unable to find mates (Zhu et al., 2009). A shortage of women also contributes to increased crime, violence, prostitution, and trafficking of women (Brooks, 2012).

LGBTQ Prejudice

In most of the world, gay and lesbian people cannot openly and comfortably disclose who they are and whom they love (Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; UN, 2011). Although by 2016 two dozen countries had allowed same-sex marriage, dozens more had laws criminalizing same-sex relationships. Cultural variation is enormous—ranging from the 98 percent in Ghana who say that “homosexuality is morally unacceptable” to 6 percent in Spain (Pew, 2014). Worldwide, anti-gay attitudes are most common among men, older adults, and those who are unhappy, unemployed, and less educated (Haney, 2016; Jäckle & Wenzelburger, 2015).

Explicit anti-gay prejudice, though declining in Western countries, persists. When experimenters sent thousands of responses to employment ads, those whose resumes included “Treasurer, Progressive and Socialist Alliance” received more replies than did resumes that specified “Treasurer, Gay and Lesbian Alliance” (Agerstro..m et al., 2012; Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2003; Drydakis, 2009). Other evidence has appeared in national surveys of LGBTQ Americans:

- 39 percent reported having been “rejected by a friend or family member” because of their sexual orientation or gender identity (Pew, 2013a).

- 58 percent reported being “subject to slurs or jokes” (Pew, 2013a).

- 80 percent of LGBTQ adolescents reported sexual orientation-related harassment in the prior year (GLSEN, 2012). Gays and lesbians are also America’s most at-risk group for hate crimes (Sherman, 2016).

Do attitudes and practices that label, disparage, and discriminate against gay and lesbian people increase their risk of psychological disorder and ill health? In U.S. states without protections against LGBTQ hate crime and discrimination, gay and lesbian people experience substantially higher rates of depression and related disorders, even after controlling for income and education differences. In communities where anti-gay prejudice is high, so are gay and lesbian suicide and cardiovascular deaths. In 16 states that banned same-sex marriage between 2001 and 2005, gays and lesbians (but not heterosexuals) experienced a 37 percent increase in depressive disorder rates, a 42 percent increase in alcohol use disorder, and a 248 percent increase in generalized anxiety disorder. Meanwhile, gays and lesbians in other states did not experience increased psychiatric disorders (Hatzenbuehler, 2014).

Belief Systems Prejudice

In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and the rise of terrorist groups such as ISIS, many Americans have developed irrational fear and anger directed toward all Muslims (and all those they think might be Muslim). As a result, 48 percent of Muslim Americans have reported personally experiencing discrimination in the last year—more than double the average among U.S. Jews, Catholics, and Protestants (Gallup, 2017). As opposition to Islamic mosques and immigration has flared, one observer noted that “Muslims are one of the last minorities in the United States that it is still possible to demean openly” (Kristof, 2010; Lyons et al., 2010).