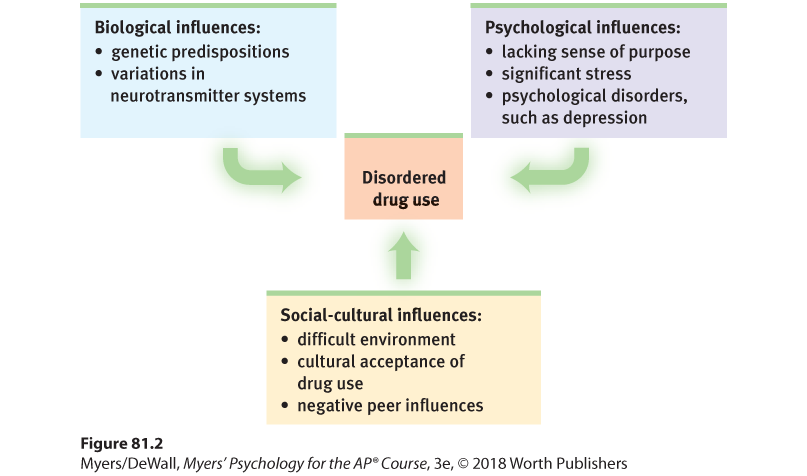

Psychological and Social-Cultural Influences

Throughout this text, you have seen that biological, psychological, and social-cultural factors interact to produce behavior. So, too, with problematic drug use (Figure 81.2). One psychological factor that has appeared in studies of youth and young adults is the feeling that life is meaningless and directionless (Newcomb & Harlow, 1986). This feeling is common among school dropouts who subsist without job skills, without privilege, and with little hope.

Figure 81.2 Biopsychosocial approach

Researchers investigate disordered drug use from complementary perspectives.

Sometimes the psychological influence is obvious. Many heavy users of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine have experienced significant stress or failure and are depressed. Girls with a history of depression, eating disorders, or sexual or physical abuse are at increased risk for problematic substance use. So are youth undergoing school or neighborhood transitions (CASA, 2003; Logan et al., 2002). By temporarily dulling their psychological pain, psychoactive drugs may offer a way to avoid coping with depression, anger, anxiety, or insomnia. (As Unit VI explained, behavior is often controlled more by its immediate consequences than by its later ones.)

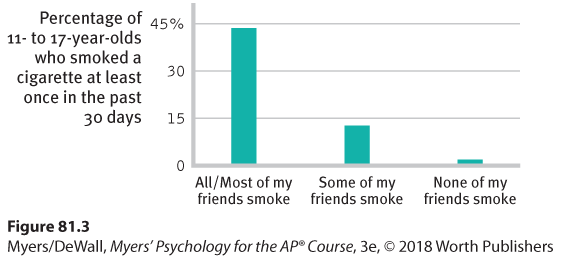

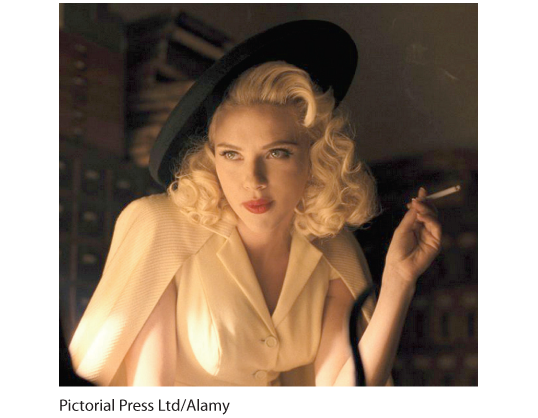

Smoking usually begins during early adolescence. (If the cigarette manufacturers haven’t made you their devoted customer by the time you reach college or university, they almost surely never will.) Adolescents, self-conscious and often thinking the world is watching their every move, are especially vulnerable to smoking’s allure. They may first light up to imitate glamorous celebrities, to project a mature image, to handle stress, or to get the social reward of acceptance by other smokers (Cin et al., 2007; DeWall & Pond, 2011; Tickle et al., 2006). Mindful of these tendencies, cigarette companies have effectively modeled smoking with themes that appeal to youths: attractiveness, independence, adventurousness, peer approval (Surgeon General, 2012). Typically, teens who start smoking also have friends who smoke, who offer them cigarettes and describe the pleasure cigarettes bring (Rose et al., 1999). Among teens whose parents and best friends are nonsmokers, the smoking rate is close to zero (Moss et al., 1992; also see Figure 81.3).

Figure 81.3 Peer influence

Kids seldom smoke if their friends don’t (Philip Morris, 2003). A correlation-causation question: Does the close link between teen smoking and friends’ smoking reflect peer influence? Teens seeking similar friends? Or both?

Rates of drug use also vary across cultural and ethnic groups. One survey of European teens found that lifetime marijuana use ranged from 5 percent in Norway to more than eight times higher in the Czech Republic (Romelsjö et al., 2014). Independent U.S. government studies of drug use in households and among high schoolers nationwide reveal that African-American teens have sharply lower rates of drinking, smoking, and cocaine use (Johnston et al., 2007). Alcohol and other drug addiction rates have also been low among actively religious people, with extremely low rates among Orthodox Jews, Mormons, Mennonites, and the Amish (DeWall et al., 2014; Salas-Wright et al., 2012).

Nic-A-Teen Virtually nobody starts smoking past the vulnerable teen years. Eager to hook customers whose addiction will give them business for years to come, cigarette companies target teens. Portrayals of smoking by popular actors, such as Scarlett Johansson in Hail, Caesar!, tempt teens to imitate.

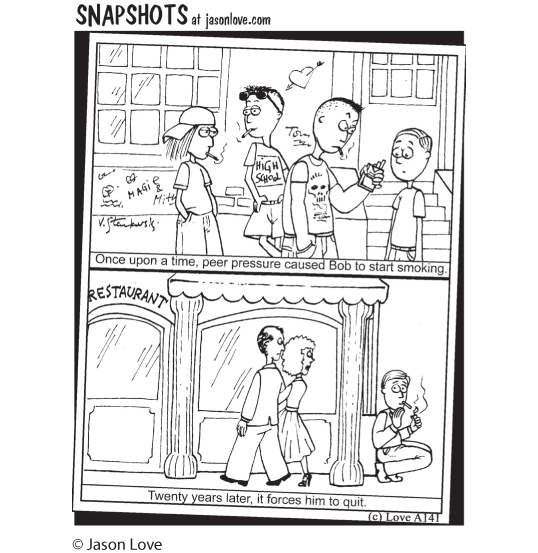

Whether in cities or rural areas, peers influence attitudes about substance use. They also throw the parties and provide (or don’t provide) the drugs. If an adolescent’s friends use drugs, the odds are that he or she will, too. If the friends do not, the opportunity may not even arise. Teens who come from happy families, who do not begin drinking before age 15, and who do well in school tend not to use drugs, largely because they rarely associate with those who do (Bachman et al., 2007; Hingson et al., 2006; Odgers et al., 2008).

Peer influence is more than what friends do or say. Adolescents’ expectations—what they believe friends are doing and favoring—influence their behavior (Vitória et al., 2009). One study surveyed sixth graders in 22 U.S. states. How many believed their friends had smoked marijuana? About 14 percent. How many of those friends acknowledged doing so? Only 4 percent (Wren, 1999). University students are not immune to such misperceptions: Drinking dominates social occasions partly because students overestimate their peers’ enthusiasm for alcohol and underestimate their views of its risks (Miller & Prentice, 2016; Self, 1994) (Table 81.1). When students’ overestimates of peer drinking are corrected, alcohol use often subsides (Moreira et al., 2009).

|

|

|

Source: NCASA, 2007.

People whose beginning use of drugs was influenced by their peers are more likely to stop using when friends stop or their social network changes (Chassin & MacKinnon, 2015). One study that followed 12,000 adults over 32 years found that smokers tend to quit in clusters (Christakis & Fowler, 2008). Within a social network, the odds of a person quitting increased when a spouse, friend, or co-worker stopped smoking. Similarly, most soldiers who engaged in problematic drug use while in Vietnam ceased their drug use after returning home (Robins et al., 1974).

As always with correlations, the traffic between friends’ drug use and our own may be two-way: Our friends influence us. Social networks matter. But we also select as friends those who share our likes and dislikes.

What do the findings on drug use suggest for drug prevention and treatment programs? Three channels of influence seem possible:

- Educate young people about the long-term costs of a drug’s temporary pleasures.

- Help young people find other ways to boost their self-esteem and discover their purpose in life.

- Attempt to modify peer associations or to “inoculate” youth against peer pressures by training them in refusal skills.

“ Substance use disorders don’t discriminate; they affect the rich and the poor; they affect all ethnic groups. This is a public health crisis, but we do have solutions.”

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, 2016

People rarely abuse drugs if they understand the physical and psychological costs, feel good about themselves and the direction their lives are taking, and are in a peer group that disapproves of using drugs. These educational, psychological, and social-cultural factors may help explain why 26 percent of U.S. high school dropouts, but only 6 percent of those with a postgraduate education, report smoking (CDC, 2011).