Human Factors Psychology

Designs sometimes neglect the human factor. Cognitive scientist Donald Norman (2001) bemoaned the complexity of assembling his new HDTV, related components, and seven remotes into a usable home theater system: “I was VP of Advanced Technology at Apple. I can program dozens of computers in dozens of languages. I understand television, really, I do. . . . It doesn’t matter: I am overwhelmed.”

Human factors psychologists work with designers and engineers to tailor appliances, machines, and work settings to our natural perceptions and inclinations. Bank ATM machines are internally more complex than remote controls ever were, yet thanks to human factors engineering, ATMs are easier to operate. Digital recorders have solved the TV recording problem with a simple select-and-click menu system (“record that one”). Apple similarly engineered easy usability with the iPhone and iPad. Handheld and wearable technologies are increasingly making use of haptic (touch-based) feedback—opening a phone with a thumbprint, sharing your heartbeat via a smartwatch, or having GPS directional instructions (“turn left” arrow) “drawn” on your skin with other wrist-worn devices.

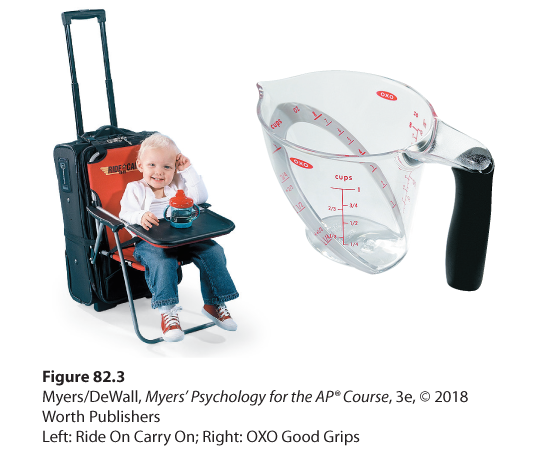

Norman hosts a website (jnd.org) that illustrates good designs that fit people (Figure 82.3). Human factors psychologists also help design efficient environments. An ideal kitchen layout, researchers have found, puts needed items close to their usage point and near eye level. It locates work areas to enable doing tasks in order, such as placing the refrigerator, stove, and sink in a triangle. It creates counters that enable hands to work at or slightly below elbow height (Boehm-Davis, 2005).

Figure 82.3 Designing products that fit people

Human factors expert Donald Norman offers these and other examples of effectively designed products. The Ride On Carry On foldable chair attachment, “designed by a flight attendant mom,” enables a small suitcase to double as a stroller. The Oxo measuring cup allows the user to see the quantity from above.

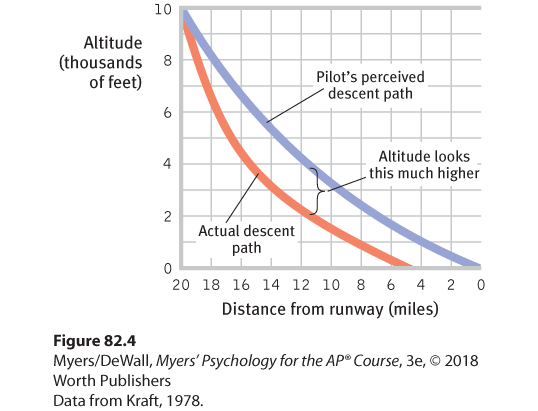

Understanding human factors can help prevent accidents. By studying the human factor in driving accidents, psychologists seek to devise ways to reduce the distractions, fatigue, and inattention that contribute to 1.25 million annual worldwide traffic fatalities (WHO, 2016). At least two-thirds of commercial air accidents have been caused by human error (Shappell et al., 2007). After beginning commercial flights in the 1960s, the Boeing 727 was involved in several landing accidents caused by pilot error. Psychologist Conrad Kraft (1978) noted a common setting for these accidents: All took place at night, and all involved landing short of the runway after crossing a dark stretch of water or unilluminated ground. Kraft reasoned that, on rising terrain, city lights beyond the runway would project a larger retinal image, making the ground seem farther away than it was. By re-creating these conditions in flight simulations, Kraft discovered that pilots were deceived into thinking they were flying higher than their actual altitudes (Figure 82.4). Aided by Kraft’s finding, the airlines began requiring the co-pilot to monitor the altimeter—calling out altitudes during the descent—and the accidents diminished.

Figure 82.4 The human factor in accidents

Lacking distance cues when approaching a runway from over a dark surface, pilots simulating a night landing tended to fly too low.

Human factors psychologists can also help us to function in other settings. Consider the available assistive listening technologies in various theaters, auditoriums, and places of worship. One technology, commonly available in the United States, requires a headset attached to a pocket-sized receiver. The well-meaning people who provide these systems correctly understand that the technology puts sound directly into the user’s ears. Alas, few people with hearing loss elect the hassle and embarrassment of locating, requesting, wearing, and returning a conspicuous headset. Most such units therefore sit in closets. Britain, the Scandinavian countries, Australia, and now many parts of the United States have instead installed loop systems (see hearingloop.org) that broadcast customized sound directly through a person’s own hearing aid. When suitably equipped, a hearing aid can be transformed by a discreet touch of a switch into a customized in-the-ear speaker. When offered convenient, inconspicuous, personalized sound, many more people elect to use assistive listening.

Designs that enable safe, easy, and effective interactions between people and technology often seem obvious after the fact. Why, then, aren’t they more common? Technology developers, like all of us, sometimes mistakenly assume that others share their expertise—that what’s clear to them will similarly be clear to others (Camerer et al., 1989; Nickerson, 1999). When people rap their knuckles on a table to convey a familiar tune (try this with a friend), they often expect their listener to recognize it. But for the listener, this is a near-impossible task (Newton, 1991). When you know a thing, it’s hard to mentally simulate what it’s like not to know, and that is called the curse of knowledge.

The human factor in safe landings Advanced cockpit design and rehearsed emergency procedures aided pilot Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, a U.S. Air Force Academy graduate who earned a Master’s degree in industrial psychology. In 2009, Sullenberger’s instantaneous decisions safely guided his disabled airplane onto New York City’s Hudson River, where all 155 of the passengers and crew were safely evacuated.

“ The better you know something, the less you remember about how hard it was to learn.”

Psychologist Steven Pinker, The Sense of Style, 2014

The point to remember: Everyone benefits when designers and engineers tailor machines, technologies, and environments to fit human abilities and behaviors, when they user-test their work before production and distribution, and when they remain mindful of the curse of knowledge.