Do Other Species Share Our Cognitive Skills?

Other animals are surprisingly smart (de Waal, 2016) (Figure 83.1). In her 1908 book, The Animal Mind, pioneering psychologist Margaret Floy Washburn argued that animal consciousness and intelligence can be inferred from their behavior. In 2012, neuroscientists convening at the University of Cambridge added that animal consciousness can also be inferred from their brains: “Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds,” possess the neural networks “that generate consciousness” (Low, 2012). Consider, then, what animal brains can do. Module 34 described animals displaying insight, but here are some other animal tricks.

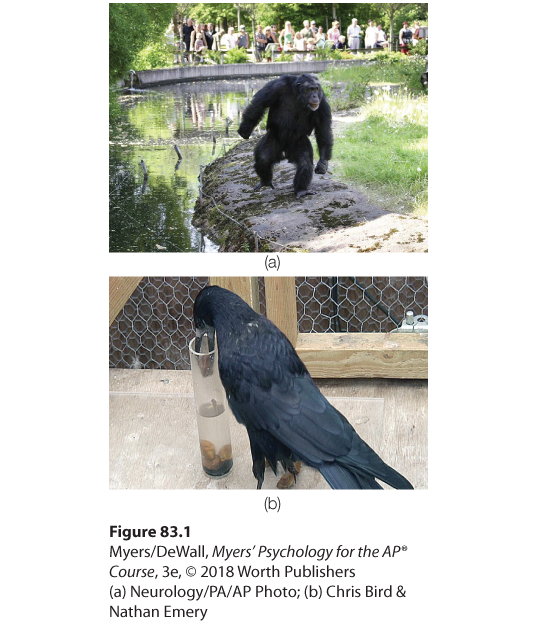

Figure 83.1 Animal talents

(a) One male chimpanzee in Sweden’s Furuvik Zoo was observed every morning collecting stones into a neat little pile, which later in the day he used as ammunition to pelt visitors (Osvath & Karvonen, 2012). (b) Crows studied by Christopher Bird and Nathan Emery (2009) quickly learned to raise the water level in a tube and nab a floating worm by dropping in stones. Other crows have used twigs to probe for insects, and bent strips of metal to reach food.

Using Concepts and Numbers

By touching screens in quest of a food reward, black bears have learned to sort pictures into animal and nonanimal categories, or concepts (Vonk et al., 2012). Chimpanzees, gorillas, and monkeys also form concepts, such as cat and dog. After monkeys have learned these concepts, certain frontal lobe neurons in their brain fire in response to new “cat-like” images, others to new “dog-like” images (Freedman et al., 2001). Even pigeons—mere birdbrains—can sort objects (pictures of cars, cats, chairs, flowers) into categories. Shown a picture of a never-before-seen chair, pigeons will reliably peck a key that represents chairs (Wasserman, 1995).

Transmitting Culture

Like humans, other species invent behaviors and transmit cultural patterns to their observing peers and offspring (Boesch-Achermann & Boesch, 1993). Forest-dwelling chimpanzees select different tools for different purposes—a heavy stick for making holes, a light, flexible stick for fishing for termites, a pointed stick for roasting marshmallows. (Just kidding: They don’t roast marshmallows, but they have surprised us with their sophisticated tool use [Sanz et al., 2004]). Researchers have found at least 39 local customs related to chimpanzee tool use, grooming, and courtship (Claidière & Whiten, 2012; Whiten & Boesch, 2001). One group may slurp termites directly from a stick, another group may pluck them off individually. One group may break nuts with a stone hammer, while their neighbors use a wooden hammer. One chimpanzee discovered that tree moss could absorb water for drinking from a waterhole, and within six days seven other observant chimpanzees began doing the same (Hobaiter et al., 2014). These transmitted behaviors, along with differing communication and hunting styles, are the chimpanzee version of cultural diversity.

Several experiments have brought chimpanzee and baboon cultural transmission into the laboratory (Claidière et al., 2014; Horner et al., 2006). If Chimpanzee A obtains food either by sliding or by lifting a door, Chimpanzee B will then typically do the same to get food. And so will Chimpanzee C after observing Chimpanzee B. Across a chain of six animals, chimpanzees see, and chimpanzees do.

Other Cognitive Skills

Animal cognition in action Until his death in 2007, Alex, an African Grey parrot, categorized and named objects (Pepperberg, 2009, 2012, 2013). Among his jaw-dropping numerical skills was the ability to comprehend numbers up to 8. He could speak the number of objects. He could add two small clusters of objects and announce the sum. He could indicate which of two numbers was greater. And he gave correct answers when shown various groups of objects. Asked, for example, “What color four?” (meaning “What’s the color of the objects of which there are four?”), he could speak the answer.

A baboon in an 80-member troop can distinguish every other member’s voice (Jolly, 2007). Great apes, dolphins, and elephants recognize themselves in a mirror, demonstrating self-awareness. Dolphins form coalitions, cooperatively hunt, and learn tool use from one another (Bearzi & Stanford, 2010). In Shark Bay, Western Australia, a small group of dolphins learned to use marine sponges as protective nose guards when probing the sea floor for fish (Krützen et al., 2005). Elephants also display their abilities to learn, remember, discriminate smells, empathize, cooperate, teach, and spontaneously use tools (Byrne et al., 2009). Chimpanzees show altruism, cooperation, and group aggression. Like humans, they will purposefully kill their neighbor to gain land, and they grieve over dead relatives (Anderson et al., 2010; Biro et al., 2010; Mitani et al., 2010).

* * *

There is no question that other species display many remarkable cognitive skills. But one big question remains: Do they, like humans, exhibit language?