Appendix II

Supplements from the Notes of Oskar Becker

1. Continentia

[Supplement to § 12 a]

“Jubes continentiam” [you command continence]—the iubere [commanding] is a directio cordis [direction of the heart]. Cf. Enarrationes in Psalmos [On the Psalms] 7, V. 10: iubere is not oriented in the Church, in objective faith.

“Quomodo ergo justus dirigi potest, nisi in occulto.” [For how can the just man be directed except in secret.]1 Through events at the beginning of the Christian age, the effectivity of God could indeed once be experienced objectively as a miracle. But now, when the name of Christians has grown to such heights, the hypocrisis—the hypocrisy of those who want to please people rather than God—grows as well. How else can the just one be led out of such confusio simulationis [confusion of simulation], if not by God's testing him in the heart and gut (Cor, heart = inner consideration; ren, gut = delectatio in malam partem [delight in the bad parts]. The delectatio is something base in life; that is why it is designated by a baser, lower organ.) Augustine now elaborates, in what this scrutinium [scrutiny] is enacted.—“Finis enim curae delectatio est” [For the end of concern is delight]:2 For everyone strives in his concern and consideration for what is attainable by his own delectatio, but God himself speaks in our conscience, and he sees our concern and our goal; that which we are doing through actions and words may be known to a human being, “sed quo animo fiant” [but what we do in the soul],3 and what we thus aim at, God alone knows.

Iubes continentiam is to be understood in this sense.

2. Uti and frui

[Supplement to § 12 b]

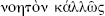

The curare (the being-concerned) is a basic characteristic of life, it is meant as vox media in bonam et in malam partem [the middle voice between the good and the bad parts]: there is genuine and non-genuine concern (the latter = “bustling activity”).

Uti [use]: I “deal with” what life brings to me; this is a phenomenon within the curare.

Frui: “enjoying.”—”Beatus est quippe qui fruitur summo bono.” [Happy is he who indeed enjoys the highest good.]4 A certain basic aesthetic meaning lies in this; one notices the Neo-Platonic influence: the beautiful belongs to the essence of being.

And then we also say that a thing is a joy if it is such “quae nos non aliud referenda per se ipsa delectat” [that it gives us delight in itself, not by reference to something else].5

As uti, we grasp that way of pleasing in which we strive for something for the sake of something else (“uti vero ea re [dicimur], quam propter aliud quaerimus” [but (we are said) to use something we need for the sake of something else]6).

In enjoyment, we are said to possess eternal and unchangeable things. The appropriate comportment to the other things is uti, since precisely through this, we will attain to the frui of what is genuine (cf. De doctrina Christiana, lib. 1, cap. 22).

Only the trinitas [trinity] must be held in enjoyment, that is the highest and unchangeable good.

Fruendum est rebus invisibilibus. [To be enjoyed is the invisible thing.] “Frui enim est amore alicui rei inhaerere propter seipsam. Uti autem, quod in usum venerit ad id quod amas obtinendum referre, si tamen amandum est.” [For to enjoy a thing is to stay in love for it for its own sake. To use, on the other hand, is to use whatever means are at one's disposal to obtain what one loves, if only it is loved.]7

“Omnis itaque humana perversio est, […], fruendis uti velle, atque utendis frui. Et rursus omnis ordinatio, quae virtus etiam nominatur, fruendis frui, et utendis uti.” [However, all human perversion is (…) the will to use for the sake of enjoyment, and to enjoy for the sake of use. By contrast, all order which is to be called virtue demands that one enjoy for the sake of enjoyment, and use for the sake of use.] (De diversis quaestionibus octoginta tribus, quaest. 30 [83 Various Questions, 30]; written soon after Augustine's conversion).8

Aesthetic basic meaning of frui; fruendum est trinitate, rei intelligibilis pulchritudo [?] (=  )[?]; incommutabilis et ineffabilis pulchritudo = God [to be enjoyed is the trinity, the beauty of intelligible things (=

)[?]; incommutabilis et ineffabilis pulchritudo = God [to be enjoyed is the trinity, the beauty of intelligible things (=  ); unchangeable and ineffable beauty = God]. The frui is thus the basic characteristic of the Augustinian basic posture toward life itself. Its correlate is the pulchritudo; thus there is an aesthetic moment in it. Likewise in the summum bonum.—With this, a basic aspect of the medieval object of theology (and of the history of ideas in general) has been designated: it is the specifically Greek view. The “fruitio Dei” [enjoyment of God] is a decisive concept in medieval theology; this basic motif led to the formation of medieval mysticism.

); unchangeable and ineffable beauty = God]. The frui is thus the basic characteristic of the Augustinian basic posture toward life itself. Its correlate is the pulchritudo; thus there is an aesthetic moment in it. Likewise in the summum bonum.—With this, a basic aspect of the medieval object of theology (and of the history of ideas in general) has been designated: it is the specifically Greek view. The “fruitio Dei” [enjoyment of God] is a decisive concept in medieval theology; this basic motif led to the formation of medieval mysticism.

However, the “fruitio” in Augustine is not the specifically Plotinian one, which culminates in intuition, but is rooted in the peculiarly Christian view of factical life.

In the end, the fruitio Dei is opposed to the possession of the self; they do not stem from the same root, but have grown together from without.

Connected to this is the fact that for Augustine, the goal of life is the quies [rest]. Vita praesens: “in re laboris, sed in spe quietis; in caren vetustatis, sed in fide novitatis” [Present life: “in actual labor, but in hope of rest; in the flesh of aging old life, but in faith of the new”].9—In the flesh ( in Paul not only sensual libido, but factical life in general) of decay (falling), in faith in the renewal.

in Paul not only sensual libido, but factical life in general) of decay (falling), in faith in the renewal.

“Quo praecedit spes vestra, sequatur vita vestra.” [Whither your hope moves ahead, let your life follow.]10 Life is enacted in the direction of that toward which expectation runs ahead.

Schematic Overview of the Phenomena

The curare [concern] consists of the uti and frui.—The basic direction of vita: the delectatio.—The tentatio lies in the delectatio itself. It has the possibilities of turning into the defluxus [flowing out, sliding down, scattering] and the continentia [continence].

3. Tentatio

[Supplement following § 12 b]

Tentatio (c. 28): Different meanings of tentatio: tentatio deceptionis [temptation of deception]: with the tendency to bring-to-a-fall; 2. tentatio probationis [temptation of probation]: with the t[endency] to test. In the first sense, only the devil (diabolus) tempts, in the second, God tempts too.11

“Diabolus”: in Augustine, there is here still vivid a belief in demons with concrete ideas, but this is not all: see Letter 146.

No human being is equipped with justice to such a degree that no appeal [Anfechtung] of confusion would be necessary for him.12 This is the real tentatio, the tentatio tribulationis, so that the human being becomes a question to himself. It is necessary “vel ad perficiendam, vel ad confirmandam” [be it for perfection, be it for confirmation].13

“Nescit se homo, nisi in tentatione discat se” [You do not know a human being unless you have gotten to know him in temptation].14 A human being does not know himself at all unless he gets to know himself in tentatio. One notices the historical basic meaning of discere [to learn, to get to know], which takes place in concrete, factical, historical self-experience. Tentatio is a specifically historical concept.

“Amores duo in hac vita secum in omni tentatione luctantur, amor saeculi, et amor Dei” [In all temptation, two kinds of love are struggling with one another in this life: love of the world, and love of God].15 On the concept of diabolus, cf. Enarrationes in Psalmos, ad. Ps. 148.

Within us, the appeal [Anfechtung] and […]* struggle daily, not always for […],* for we also bear […],* and there is a constant danger within us, so that he who is not awake will be conquered; but if we do not consent, we do indeed gain the upper hand; but in this too, there is a burden, resistendo delectationibus [resisting delight].16

Paul, Gal. 5:17; “Caro enim concupiscit adversus spiritum” [For what the flesh desires is against the spirit]. You do not do what you want, and that is a struggle; and what makes it even more burdensome is the fact that it is an inner struggle.

“In quo bello si sit quisque victor, illos quos non videt inimicos, continuo superabit. Non enim tentat diabolus vel angeli ejus, nisi quod in te carnale dominatur [is alive in this real facticity]” [And in this war, each one who is victorious will straightaway overcome enemies whom he does not see. For the devils and his angels do not tempt, except the carnal part that rules in you (is alive in this real facticity)].17

And when the devil tempts someone in whatever manner, he always tempts the one who agrees with him, “non cogit invitum” [he does not force a person against that person's will]; he seizes only the one “quem invenerit ex aliqua parte jam similem sibi” [whom he finds to be in some part like himself], and thus, the gate is open for the entry of devilish suggestion (iunua tentatione [the gate of temptation]).18

The emergence of tentatio from factical life takes place on different levels. Division of phenomena: in concretely tangible temptations (for example, sexual ones), and not concretely tangible ones (mental ones, performed in cogitatio [thought]).

The tentatio has a twofold connection to the authentic experiences of the self.

In what basic direction of experience does it itself have its sense? We must go back to its authentic basis of enactment. Here is an opportunity to refer [to] a connection we have not seen so far, a connection between Augustine and Neo-Platonism!

Augustine assumes a concrete situation of temptation (in “De doctrina Christiana”): living-in-avarice (avaritia). What is decisive is the dilectio [esteem, love], the amor pecuniae [love of money]. What kind of delectatio [delight] is dominant will become decisive for one's comportment in the appeal [Anfechtung] and in coping with it.

From the outside, the devil suggests a gain, one which, however, requires fraud. He places before you what you have overcome internally. (That is, something significant that corresponds to the relational direction of the experience that is already alive in that human being.) If you defeat avarice, if it is internally dominated in you, the temptation will have been overcome. Everything depends on the dominant direction of delectatio. But an expectation always remains alive. Something else, however, may be placed before expectation, so that an inner struggle emerges. The human being is placed before a decision. “You are broken within yourself by sin.” (“Etenim ex peccato divisus es adversum te” [For through sin are you divided against yourself].19) “Habes contra quod pugnes in te, habes quod expugnes in te” [You have within you that with which to fight, you have within you what to overcome].20 Implied in this is the fact that, in considering the tentatio, what is crucial is not the objective situation that leads to the temptation, but the situation of self of he who experiences it. In each case, something different is required; when you are struggling, when you are victorious, when you rejoice, for instance, a gain is set before you, delectationem habet [it has delight]. “Suggeritur aliquod lucrum, delectat, habet fraudem, sed magnum est lucrum, delectat, non consentis” [Some gain is suggested to you, you take delight in it, it involves deceit, but great is the gain, and you take delight in it, yet you do not consent].21 The persuasion and urging is still going on. Already considered. Already fallen. “Contempsit justitiam, ut fraudem faceret” [He has thought lightly of justice so that he may commit deceit],22 or: contempsit lucrum [He has thought lightly of his gain] for the sake of justice. “Sed etiam ille qui vicit, numquid omnino egit in se” [But even he who was victorious, has he altogether achieved in himself]23 that money cannot trouble him any longer? “Aut nihil in eo excitet delectationes” [That it excites in him no delight]?24 Although money no longer seems to him to be worth the struggle, “inest tamen aliqua delectationes titillatio” [yet there is in him a titillation of delight].25 This titillation is present and remains in the human being, even if temptation is no longer present. (Here, Augustine comes to the problem of original sin.)

The role played by the setting-before and setting-after shows that a certain ordo [order] is the basis of the phenomenon. You belong to God, but the flesh belongs to you (the flesh refers to what is at one's disposal in factical life). You belong to what is higher in value, the lower value belongs to you. It is not the following order that we recognize and recommend: “Tibi caro et tu Deo; sed, Tu Deo, et tibi caro. Si autem contemnis Tu Deo, nunquam efficies ut Tibi caro. […] Primo ergo te subdas Deo” [“Your flesh to you, and you to God,” but “you to God, and your flesh to you.” For if you despise “You to God,” you will never bring about “your flesh to you.” (…) First, then, submit yourself to God; then, with Him to teach you and encourage you, fight],26 then you will struggle in his illumination and under his guidance. It does not only depend on the relation to God, but on the How of the ordo. “Agnosce ordinem” [Observe order],27 put in modern terms: Observe the ranking order of values.

For us, it is important: first, how this order of rank is the basis; second, that the order is viewed in a certain conceptual form. It is not natural that that which is experienced in the delectatio stands in a ranking order of value. Rather, this is based on an “axiologization” which, in the end, is on the same level as the “theorization.” This ranking order of values is of Greek origin. (In the whole manner of concept-formation, it stems ultimately from Plato.) Proof of this is, among other things, the connection to the incommutabile [unchangeable]. Thus, such a ranking order is already present in Augustine. However, does this axiologization correspond to the explicated phenomena?

The axiologization is more difficult to grasp than the theorization, because it actually deals with what is in question.

Chapters […]* of Book X of the Confessiones show how Augustine indeed uses a ranking order as a basis, but it ultimately takes on an essentially different meaning.

This ranking order dominates Augustine to a very large extent. However, it is not grasped in a manner as removed as it is today (for example, in Scheler); it is connected to his concrete metaphysics, and the conception of reality (res) is tailored to it.

What does Augustine mean by “res” (reality)? The modes of concern, of uti [use] and frui [enjoyment], in their relation to “res,” result in the following division into three kinds: “Res ergo aliae sunt quibus fruendum est, aliae quibus utendum, aliae qua fruuntur et utuntur” [There are some things, then, which are to be enjoyed, others which are to be used, others still which enjoy and use].28

The res [things] are opposed to the signa (signs). “Proprie autem nunc res appellavi, quae non ad significandum aliquid adhibentur, sicut est lignum, lapis, pecus, atque hujusmodi caetera” [On the other hand, a thing, properly speaking, is designated as that which is not employed to signify anything else, such as wood, stone, cattle, and other things of that kind].29 But this is not understood in the sense of the wood that Moses cast into the bitter waters, nor of the stone that Jacob put under his head, etc.—Opposition: signum = symbol. This is connected to the interpretation of Scripture and goes back to the Alexandrian school of exegetes (which, in turn, goes back to the school of philologists: problem of the interpretation of all texts). These latter things (Moses' wood, etc.) are signs of other things at the same time. But there are still other signs whose consistent and full use consists in designating itself (whereas the wood does not necessarily possess the character of indication). No one uses words for purposes other than designation. Every sign is a res, otherwise it would be nothing, but not every res is a signum. Thus, when looking at the res, we only pay attention to what they are (according to their content), not to what else they might indicate. And, vice versa, if I deal with a thing as a sign, I must pay attention not to what it is, but to the fact that it is a sign (such that I have to look away from them).30

What is the human being itself? Is he a fruendum, utendum [an object of enjoyment, of use], or both? We who fruimur et utimur [enjoy and use] are, somehow, a res [thing] ourselves. “Magna enim quaedam res est homo” [For man is a truly great thing],31 because he has reason. “Itaque magna quaestio est utrum frui se homines debeant, an uti, an utrumque” [And so it is a great question whether human beings ought to enjoy, or use themselves, or do both].32 There is the commandment of reciprocal love, but the question is whether one human being is loved by another as a human being (propter se [on account of himself]), or for the sake of something else. If a human being is loved for his own sake, fruimur eo [we enjoy him], if not, utimor eo [we use him]. However, it now seems that a human being must be loved for the sake of something else, for in that which is to be loved for its own sake, “in eo constituitur vita beata” [in this consists the happy life].33 But we do not have the res from the vita beata (we do not have the latter as such), sed spes [but hope].

If you see clearly, the human being may not even be the object of frui for itself. “Si autem se propter se diligit” [If, however, he loves himself on account of himself],34 he does not relate to God. If he is turned toward himself, he is not turned toward the unchangeable. And since that which he supposedly loves in himself is characterized by a defect (defectus, that is, transience), it is to be preferred that he is attached without defect to the incommutabile (unchangeable), rather than that he “ad seipsum relaxatur” [opens himself toward himself].35

He “qui rerum integer aestimator est” [who estimates things without prejudice],36 that is, “qui ordinatam dilectionem habet” [who has ordinate love] lives in a holy way.37

The positioning [Stellungnahme] within the tentatio is enacted from this ordo [order]; from it, the basic comportment to things is decided.

This doctrine of value is already on a high level of forming-out. But one misperceives it if one isolates it and does not view it in its context. Then the problem emerges whether such ranking order of values is a meaningfully necessary one, or whether it does not merely rely on the role Greek philosophy plays in Augustine's thought.

More on the doctrine of value: “Non autem omnia quibus utendum est, diligenda sunt, sed ea sola quae aut nobiscum societate quadam referuntur in Deum [being related to God on the basis of a community with us].” [However, not all those things which are to be used, are to be loved, but only those which are in a community with us in relation to God (being related to God on the basis of a community with us).]38 (Here lies the origin of the thought of Christian solidarity).

Those things deserve an estimation of love that are related to us, but “beneficio Dei per nos indigent, sicuti est corpus [the flesh as the seat of sin]” [they need the goodness of God through us, such as the body (the flesh as the seat of sin)].39 Thus, there are four kinds of objects that are to be loved: (1) What is above us. (2) What we are ourselves. (3) What is next to us. (4) What is beneath us.

Regarding (2) and (4), no special reason is required to love them. However much a human being may fall from the truth, the self-esteem and the esteem of his body remains intact. “Nemo ergo se odit” [No man, then, hates himself].40 But because of self-love of a certain kind, commandments of a certain order are necessary. The human being has a certain posture in relation to himself, since his self-esteem is there by itself with the facticity of life. (This comprises a certain phenomenal complex of self-experience, which is to be explicated.)

He who is the integer aestimator rerum [unprejudiced estimator of things], who possesses the ordinata dilectio [ordinate love] loves in an authentic way, so that he does not either love what may not be loved at all, or love that more which may not be loved more, etc.41 (A certain formalism lies in this stratification of the order of value.)

However, one may not remove this order of value-ranking from its cultural-historical context, from the peculiar entwinement of Greek philosophy (in particular, Platonism) with the Christian view of life.

In considering the following chapters of the “Confessiones” (lib. X, cap. 30 ff.), we will have to pay attention to the following four groups of problems:

1. The problem of “tentatio.” In this, the complex of enactment of my concrete full self-experience: how I decide.—From the problem of tentatio, we will get to the basic sense of self-experience as historical.

2. Connected to the tentatio is the “defluxus in multum” [flowing into the many] (into the multiplicity of the significances of factical life). The “molestia” (burden, trouble) proves to be constitutive for the concept of facticity.

3. The problem of the meaning of “quaestio mihi factus sum” [I have become a question to myself]. The becoming-a-question-to-oneself is meaningful only in the concrete context of self-experience. It is not a question of objective presence, but of authentic selfly existence.

4. The problem of the basic orientation of dilectio in a determinate axio-logical system.—It is to be decided to what extent this originates from one's own experience, and to what extent it can be demonstrated to have been determined by the cultural-historical situation of Augustine.

The problem of the universal theory of value is connected to Neo-Platonism and the doctrine of the summum bonum, in particular, to the conception of the way in which the summum bonum becomes accessible. The Pauline passage of the Letter to the Romans, chapter 1:20, is fundamental for the whole of Patristic “philosophy,” for the orientation of the formation of Christian doctrine in Greek philosophy. The motif for the Greek underlying structure and re-structuring [Unter- und Neubau] of Christian dogmatism has been taken from this passage. However, this “pre-structure” [Vor-bau] was then structured into the basic patterns of the Christian thought of the dogmatism. For this reason, one cannot simply dismiss the Platonic in Augustine; and it is a misunderstanding to believe that in going back to Augustine, one can gain the authentically Christian.

Rom. 1:19 f. says:  .

.

…Since the estimation of the world, what is invisible in God is seen by thought in His works.

…Since the estimation of the world, what is invisible in God is seen by thought in His works.

This proposition returns again and again in Patristic writings; it gives direction to the (Platonic) ascent from the sensible world to the supersensible world. It is (or is grasped as) the confirmation of Platonism, taken from Paul.

However, this is a misunderstanding of the passage from Paul. Only Luther really understood this passage for the first time. In his earliest works, Luther opened up a new understanding of primordial Christianity. Later on, he himself fell victim to the burden of tradition: then, the beginning of Protestant scholasticism sets in.

The insights of Luther's early period are decisive for the cultural [geistigen] connections of Christianity to culture. Today, this is misperceived in the concern for Christian-religious renewal.

Luther's view finds a clear expression in his 1518 Heidelberg Dissertation. In it, he defends forty theses: twenty-eight theological ones and twelve philosophical ones. For us, the theses 19, 21, and 22 are important here.

(19) “Non ille digne Theologus dicitur, qui invisibilia Dei per ea, quae facta sunt, intellecta conspicit” [The man who looks upon the invisible things of God as they are perceived in created things does not deserve to be called a theologian].42 He who sees what is invisible of God in what has been created, is no theologian.—The presentation [Vorgabe] of the object of theology is not attained by way of a metaphysical consideration of the world.

(21) ”Theologus gloriae dicit malum bonum et bonum malum, Theologus crucis dicit id quod res est” [The theologian of glory calls evil good and good evil, while the theologian of the cross says what a thing is].43 The theologus gloriae who aesthetically takes delight in the wonders of the world, names what is sensible in God. The theologian of the cross says how things are.

(22) ”Sapientia illa, quae invisibilia Dei ex operibus intellecta conspicit, omnino inflat, excaecat et indurat” [The wisdom that looks upon the invisible things of God from His works, inflates us, blinds us, and hardens our heart].44Your wisdom that sees what is invisible of God in His works, inflates, blinds us, and hardens us.

4. The confiteri and the Concept of Sin

[Supplement following § 13 b]

It is important that the molestia belongs to facticity, a belonging-together that arises in one's own experiencing, just as the continuous experiencing of, and self-confrontation with, molestia belongs to authentic life. Later on, the molestia is intellectualized [vergeistigt]; the tentatio is no longer sensuousmaterial, but more hidden and more dangerous. With this, the sense of facticity, and the sense of the “quaestio mihi factus sum” [I have become a question to myself], increase.

Thus, we have treated four basic phenomena, which are important for the further discussion of the Confessiones:

(1) the tentatio; (2) the defluxus in multum [flowing into the many] and the molestia; (3) the “quaestio mihi factus sum”; (4) the question of the axiological forming-out.

In our further interpretation, we have to take into account two things:

1. That Augustine communicates all phenomena in the posture of the confiteri [to confess], standing within the task of searching and of having God. The reference to the authentic condition of the enactment of experiencing God is important. The condition is such that, if one takes it seriously, one (initially) moves away from God. With the “quaestio mihi factus sum,” the distance to God increases.

2. That our possibility of interpretation has its limits, for the problem of confiteri arises from the consciousness of one's own sin. The tendency toward vita beata [the happy life]—not in re [in actuality] but in spe [in hope]—emerges only from out of the remissio peccatorum [remission of sins], the reconciliation with God. But we have to leave aside here these phenomena because they are very difficult and require conditions of understanding that cannot be achieved in this context. However, in our consideration, which is of the order of understanding, we will gain what is basic for the access to those phenomena of sin, grace, etc. However, the consciousness of sin—and the manner in which God is present in it—stands, in Augustine, in a peculiar interrelation to Neo-Platonism. (For this reason, his conception of sin cannot […]* guide the phenomenological explication of the “genuine” phenomenon.)

In Augustine, the concept of sin has a threefold character:

1. A theoretical one: sin as privatio boni [privation of the good], oriented toward the summum bonum [highest good]. Sin is a lower measure of reality; for this reason, it bears within itself a higher measure of mortality so that it itself is death, so that death is given with it.—These are Plotinian ideas that connect to a certain conception of Paul's thoughts in the Letter to the Romans.

2. An aesthetic one: Cf. for this the beginning of Confessiones Bk. VIII, ch. 7.—After the narrative of Ponticianus about Saint Antony, it is said: “Tu autem, Domine, inter verba eius retorquebas me ad meipsum, auferens me a dorso meo ubi me posueram, dum nollem me attendere; et constituebas me ante faciem meam, ut viderem quam turpis essem, quam distortus et sordidus, maculosus et ulcerosus” [But while he spoke, You, my Lord, turned me around toward myself, so that I no longer turned back on myself where I had placed myself while I was not willing to observe myself. And you showed me my face so that I might see how ugly I was, how disfigured and dirty, blemished and ulcerous].45

3. The character of an enactment: only he loses You who leaves You; he who leaves You, to where does he flee, if not from You as the merciful one to You as the wrathful one? This is the decisive conception.

5. Augustine's Position on Art (“De Musica”)

[Supplement following § 13 e]

Ch. 33. Important for Augustine's position on art, in particular, on music. One may not extract an analysis of art from Augustine. His basic motives are important. Art must be integrated into a higher complex. Likewise, aesthetics. It must explicate the aesthetic objects such that they are grasped as a path to absolute beauty (Neo-Platonic conception!).

For this, Augustine's statement in the “Retractationes” about his book “De musica libri VI” is characteristic.

Of the six books on music, the sixth one is the most crucial one, because it deals with its object in an authentic mode of knowledge, namely in the following way: it is shown how the transition is possible from the sensible and mental relations of numbers, which themselves are changeable, to the unchangeable relations of numbers, which themselves are in unchangeable truth.

“De musica” is Augustine's formal aesthetic; in this book, he delivers a theory of numbers and a doctrine of relations. He distinguishes five different species of “numbers” (musica ars bene modulandi [music is the art of playing well]):

1. numeri “in ipso sono” [numbers “in the sound”]46

2. numeri “in ipso sensu audientis” [numbers “in the auditory sense itself ”]47

3. numeri “in ipso actu pronuntiantis” [numbers “in the act of pronunciation”]48

4. numeri “in ipsa memoria” [numbers “in memory”]49 (as they are in consciousness)

5. numeri “in ipso naturali judicio sentiendi” [numbers “in the natural judgment of the perceiving listener”],50 or: numer iudiciales [numbers of judgment]. (In these “numbers in themselves” lies the motive of the transition toward the unchangeable.)

Augustine does not offer a psychological presentation, but the manner of comportment in listening.

Cf.in the Enarrationes in Psalmos (T) the frequent designation of the New Testament as “canticus novus” [new song].—”Cantare est res amantis” [Singing is the loving thing.]—The interpretation of art: taking art back into the wholeness of factical human life, albeit in such a way that it is not metaphysically formed-out, but has its determinate place on the basis of the order of value, from out of the summum bonum. However, these considerations may not be severed from the whole context, or else phenomena are overlooked.

Augustine's own words about “De musica” are characteristic for this: those who read these books will find that we are dealing with things in art not on the basis of taking an evasive stance in which we then dwell, but from out of the necessity to understand art itself as a path. (“Illos igitur libros qui leget, inveniet nos cum grammaticis et poeticis animis, non habitandi electione, sed itinerandi necessitate versatos” [And so, whoever reads the preceding books will find us dwelling with grammatical and poetical minds, not through choice of permanent company, but through necessity of wayfaring].51)

Even if the way is base (vilis via), the goal does not have to be base.

These writings have been written for those who deal with worldly science and literature, and who are entangled in manifold errors, and who squander their good mental capacities on little things (in nugis) without seeing what is really valuable (ibi delectat [what is delightful there]) in the objects with which they are dealing.

The entire structure of “De musica” has to be understood in this context. The individual “numeri” and their order has to be understood on the basis of the basic orientation toward the summum bonum. This order stems from Neo-Platonic aesthetics.

6. Videre (lucem) Deum [To See God (the light)]

[Supplement following § 13 g]

“Decus meum” [my glory], said about God—a Neo-Platonic thought.

“Lux” [Light], determined through the Neo-Platonic tradition and the Gospel of John, both of which go back to Greek philosophy. John 1:4:

]

]  .

.

. [In it (the word) was life, which was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it.]

. [In it (the word) was life, which was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it.]

Connection to the question of grasping God. Cf. Augustine's commentary on the Gospel of John (Tractatus in Joannis Evangelium) and Letter 146 (“De videndo Deo”); the older writings are frequently different.

Lux and lumen are to be distinguished. Lux: in an objective sense, what is present as the object of seeing (regina colorum [the queen of colors]). Lumen: brightness, always of the soul.

Cf. Quaestionem Evangeliorum libri duo: “Si quod lumen est in te tenebrae sunt, ipsae tenebrae quantae (Matth. VI, 23)? Lumen dicit bonam intentionem mentis, qua operamur: tenebras autem ipsa opera appellat, sive quia ignoratur ab aliis quo animo illa faciamus, sive quia eorum exitum etiam ipsi nescimus, id est, quomodo exeant atque proveniant eis quibus nos ea bono animo impendimus” [If the light in you is darkness, how great is the darkness itself (Matt. 6:23)? Light speaks of the good intention of the mind with which we labor: but darkness calls itself labor, be it because it does not know of another soul through which we may do things, or because we do not know their ruin even in itself, that is, how they go out and flourish through those things that we use in that good soul].52 (The […]* are those in whose direction we intended them, with good intentions.)

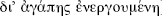

Tractatus de Joannis Evangelio I 18 (on John 1:4): “Et vita erat lux hominum; et ex ipsa vita [Verbi] homines illuminantur. Pecora non illuminantur, quia pecora non habent rationales mentes, quae possint videre sapientiam” [And life was the light of men; and through the life itself [of the word] men are illuminated. Animals are not illuminated because animals have no rational minds which are able to see wisdom].53 (The truth of life; not theoretical.) 1:19: “Sed forte stulta corda adhuc capere istam lucem non possunt, quia peccatis suis aggravantur […] Non ideo cogitent quasi absentem esse lucem, […]: ipsi enim propter peccata tenebrae sunt” [But perhaps foolish hearts cannot grasp that light because they are weighed down by their own sins (…) But they should not think, therefore, that the light is absent (…): for they are darkness themselves because of their sins].54 “Quomodo homo positus in sole caecus, praesens est illi sol, sed ipse soli absens est [He is not to be had for the sun, whereas the sun is waiting for him; possibly, the sun is objectively at his disposal]; sic omnis stultus, omnis iniquus, omnis impius, caecus est corde. Praesens est sapientia, sed cum caeco praesens est, oculis eius absens est: […] Quid ergo faciat iste? Mundet [oculos] unde possit videri Deus. […] quia sordidus et saucios oculos haberet” [Just as a blind man stands in the sun, the sun is present to him, but he himself is absent to the sun (He is not to be had for the sun, whereas the sun is waiting for him; possibly, the sun is objectively at his disposal); so every fool, every unjust man, every impious man, is blind in his heart. Wisdom is present, but since it is present to a blind man, it is absent from his eyes: (…) So what should that man do? He is to purify (his eyes) so that God can be seen. (…) because he had sordid and wounded eyes].55 Then that which corrupts (pulvis, fumus [dust, smoke]—sin) is removed by the physician so that you can see what is meant for your eyes. “Tolle inde ista omnia, et videbis sapientiam” [Take all of this away, and you will see wisdom].56 (Matt. 5:8: for “blessed are the pure in heart,” etc.)—How does this “purification of the eyes” proceed? Through faith. Acts of the Apostles 15:9: “… ” [“and put no difference between us and them, purifying their hearts by faith” (after he purified their hearts through faith). “Mundat cor fides Dei, mundum cor videt Deum” [Faith in God purifies the heart, the pure heart sees God].57 Through what faith (“quali fide”) is the heart purified? (The demons, too, fear God and have a kind of faith in him, that is, not the right kind. Acts of the Apostles). Answer: “Fides quae per dilectionem operatur (Galat. V 6 [

” [“and put no difference between us and them, purifying their hearts by faith” (after he purified their hearts through faith). “Mundat cor fides Dei, mundum cor videt Deum” [Faith in God purifies the heart, the pure heart sees God].57 Through what faith (“quali fide”) is the heart purified? (The demons, too, fear God and have a kind of faith in him, that is, not the right kind. Acts of the Apostles). Answer: “Fides quae per dilectionem operatur (Galat. V 6 [

]) […] sperat quod Deus pollicetur. Nihil ista definitione perpensius, nihil perfectius. Ergo tria sunt illa [fides, spes, caritas]” [Faith which works through love (Gal 5:6), (…) hopes for what God promises. There is no more perfect, more thought-out definition than that. So we have these three (faith, hope, love)].58 “Comes est ergo fidei spes. Necessaria quippe spes est” [Therefore, hope is the companion of faith. Hope is indeed necessary].59 As long as we do not see what we believe. So that we do not fall. (This is a Plotinian concept, in a good Christian re-functioning.) “Tolle fidem, perit quod credis [then what he believes will perish]; tolle charitatem, perit quod agis. Fidei enim pertinet ut credas [fides = fiducia = trust, as in Luther]; charitati [pertinet], ut agas” [Take away faith, and what you believe perishes (then what he believes will perish); take away love, and what you do perishes. For it belongs to faith that you may believe (faith = trust = trust, as in Luther); (it belongs) to love that you act].60 “Et modo ipsa fides quid agit?” [And what does faith itself do?]61 All the testimonies from Scripture, all doctrines and the corresponding instructions, what do they do? Only that we see “per speculum in aenigmate” [by a mirror in an enigma].62 But merely because faith does only that, there is no reason that you, in turn, return “ad istam faciem tuam” [to that face of yours],63 to your own “makings” (that is, to what you have made of God for yourself, as an object). “Faciem cordis cogita” [Think of the face of the heart].64 (God in His objecthood [in der Gegenständlichkeit], as appropriated by the heart in its authentic life.)

]) […] sperat quod Deus pollicetur. Nihil ista definitione perpensius, nihil perfectius. Ergo tria sunt illa [fides, spes, caritas]” [Faith which works through love (Gal 5:6), (…) hopes for what God promises. There is no more perfect, more thought-out definition than that. So we have these three (faith, hope, love)].58 “Comes est ergo fidei spes. Necessaria quippe spes est” [Therefore, hope is the companion of faith. Hope is indeed necessary].59 As long as we do not see what we believe. So that we do not fall. (This is a Plotinian concept, in a good Christian re-functioning.) “Tolle fidem, perit quod credis [then what he believes will perish]; tolle charitatem, perit quod agis. Fidei enim pertinet ut credas [fides = fiducia = trust, as in Luther]; charitati [pertinet], ut agas” [Take away faith, and what you believe perishes (then what he believes will perish); take away love, and what you do perishes. For it belongs to faith that you may believe (faith = trust = trust, as in Luther); (it belongs) to love that you act].60 “Et modo ipsa fides quid agit?” [And what does faith itself do?]61 All the testimonies from Scripture, all doctrines and the corresponding instructions, what do they do? Only that we see “per speculum in aenigmate” [by a mirror in an enigma].62 But merely because faith does only that, there is no reason that you, in turn, return “ad istam faciem tuam” [to that face of yours],63 to your own “makings” (that is, to what you have made of God for yourself, as an object). “Faciem cordis cogita” [Think of the face of the heart].64 (God in His objecthood [in der Gegenständlichkeit], as appropriated by the heart in its authentic life.)

“Coge cor tuum cogitare divina” [Force your heart to think about divine matters],65 do not leave it alone. (To interpret this as subjectivism is misguided. We are dealing with the condition of access to God. God is not made; rather, the self gains the enactmental condition of the experience of God. In the concern for the selfly life, God is present. God as object in the sense of the facies cordis [face of the heart] operates in the authentic life of human beings.) Shut out all those “similar” bodily things that leap into the mind of the one thinking in this way. You cannot say (of God) “that is how he is,” but only “non est hoc” [“this is not what he is”]. When will you be able to say: “that is what God is”? “Nec cum videbis: quia ineffabile est quod videbis” [Not when you will see him, because what you will see is ineffable].66 “Cogitanti ergo tibi de Deo, occurrit aliqua fortasse in humana specie mira et amplissima magnitudo” [So when thinking about God, perhaps some vast and wonderful shape in vaguely human form occurs to you];67 for example, God is compared to an enormous human being. However, when you are engaged in this effort, [finisti alicubi] “si finisti, Deus non est. Si non finisti, facies ubi est?” [(somewhere you have reached the end of it); if you have reached the end of it, it is not God. If you have not reached the end of it, where is the face?]68 “Quid agis, stulta et carnalis cogitatio?” [What are you doing, foolish and carnal thinking?]69 You have created monstrosities for yourself; and yet you have removed yourself further and further from God. Another makes God even larger by simply adding a yard.

An objection from Scripture is raised against this (Sermo 53, ch. 12 n. 13). This matter is important for Augustine's interpretation of Scripture.

From Isaiah, a contradicting passage is drawn upon: Isa. 66:1, where God is thought of as a giant human being. Heaven is my throne. Augustine responds to this: You did not read it to its end! Who measured the heaven with the palm of his hand?

The thought of mundare [purifying], as a condition of access, is already present in the earlier philosophical writings of Augustine, a Platonic thought, in Plotinus connected to his conception of ascesis. The mundare is enacted through the fides Christiana [Christian faith] (not through demonic faith). Fides is an enactmental complex of trust and love; the posture of expectation must be present. Every cosmic-metaphysical reification of the concept of God, even as irrational concept, must be warded off. One has to appropriate the facies cordis [face of the heart] (inwardness) for oneself. God will be present in the inward human being when we will have understood what breadth, length, height, depth (latitudo, longitudo, altitudo, profundum) mean, and therewith, the sense of the infinity of God for the thought of the heart. Ponder within yourself when I say: “extension.” Do not leap away with your imagination to the measurements of earthly extension. Understand everything “in te” [in yourself]. Latitudo = richness, wealth in good works; longitudo = persistence and perseverance; altitudo = expectation of that which is above you (sursum cor [the heart upwards]); profundum = God's grace. All this is not to be understood according to an objective symbolism, but rather referred back to the enactmental sense of inner life.

Symbolism of the cross: latitudo: where the hands are fixed; longitudo: the body that stands; altitudo: the expectation of […]* G.; profundum: concealed—“inde” [from it] […]*70

Dilectio [love]: If you count it, it is one ( Plotinian […]**), but if you consider it, it contains many moments. “Si Deus dilectio, quisquis diliget dilectionem, Deum diligit” [If God is love, whoever loves love, loves God].71

Plotinian […]**), but if you consider it, it contains many moments. “Si Deus dilectio, quisquis diliget dilectionem, Deum diligit” [If God is love, whoever loves love, loves God].71

Every love includes a certain benevolence (benevolentia) for the one who is loved. (Sensuous love = amor. Dilectio relates to things of higher value.) We do not love the human being in the way the Lord asked Peter: Do you love me? But we also should not love the human being in the way gourmands talk when they say: I love wild game. The gourmand loves them only to kill them. So he loves them such that they are not (non esse). One may not love human beings in this way, assigning them into one's own aims. Friendship, however, is something like benevolentia after all, a gift of our love. But what if there were nothing of our love that we could give? Since one loves, the pure benevolence as such suffices. We ought not and may not wish for miseries that enable us to do good deeds. Take away human misery and good deeds disappear! The work of mercy disappears, but the glowing of noble love remains. Originally (per me ames [?]) [you love through me], you love the human being in happiness, to whom you have nothing to give. Such love is pure and more noble if the other is noble; you elevate yourself, you attribute to yourself the achievement and you view the other to whom you give something as submissive to you.72

So wish for an equal to whom you cannot give anything in human affairs, so that he stands with you under the one to whom nothing at all can be given by humans. In this optare [wishing], you appropriate the possibility of genuine loving.

Authentic love has a basic tendency toward the dilectum, ut sit [being loved so that he may be]. Thus, love is the will toward the being of the loved one. (The content of the sense of being must correspond to the particular kind of the loved object.)

Love of oneself [Eigenliebe] has the tendency to secure one's own being, but in the wrong way: not as self-concern but as the calculation of the experiential complex in relation to one's self-world. Thus, “self-love” [Selbstliebe] is really self-hate. (Eliminate the secondary meaning of “hate”!)

Communal-worldly love has the sense of helping the loved other toward his existence, so that he comes to himself.

Genuine love of God has the sense of wishing to make God accessible to oneself as the one who exists in an absolute sense. This is the greater difficulty of life.

The problem of the phenomenological study of “emotional acts,” placed in the framework of the schema of the complex and order of value-ranking, is nonsensical. The problem of love must be removed from the “axiological” realm. F. Brentano's so-called “phenomenological” analysis of acts runs exactly counter to the genuine tendency of phenomenology.

Objecthood of God. Deus lux, dilectio, summum bonum, incommutabilis substantia, summa pulchritudo [God the light, highest God, unchangeable substance, highest beauty].

In each of these determinations, different modes of access, and different modes of the point of departure and of the motive for the access, show themselves. Further, different modes within the access, within what is experienced in the access to be explicated later. (The means of determination will be taken from different fields.) Finally, different modes of forming-out through the means of explication, which are at times self-illuminating—that is, they arise from a new point of departure in one's own experience—at other times, they keep within the traditional framework (sometimes entirely, sometimes in a modified form).—On the whole, however, the explication of the experience of God in Augustine is specifically “Greek” (in the sense in which our entire philosophy is still “Greek”). We have not arrived at a radical critical posing of the question and consideration of the origin (destruction).

This is especially true in reference to the determination of the objecthood of God from the modes of access. (Here, it is also questionable whether all modes of access themselves are original!) The modes of access have a connection in the current enactment, in the facticity of experience itself. An orientation toward the different attitudinal possibilities, faculties of reason, and the like, leads us astray, both in an ordering classification and in a “transcendental” formulation of the problem. One has to liberate oneself from this if one wishes to understand the problems of enactment. This “liberation” is not enacted all at once; rather, it is itself a task of gaining access as such.

For this problem, Augustine's treatment of the tentationes may serve as a guide. For the different directions of the tentationes are not gained by way of a classification according to the faculties of the soul, but in the factical enactment of (Christian) life. This becomes clear in progressing from the concupiscientia carnis [desires of the flesh] to the ambitio saeculi [secular ambition].

7. Intermediary Consideration of timor castus [chaste fear]

[Supplement following § 16]

As a complementary discussion, the phenomena of the love of God and the fear of God shall be treated in view of the objecthood of God that is rendered closer through them.

By falling into tentatio, one forsakes the possibility of a genuine love and of a pure fear of God: “vel […] non amare te, nec caste timere te” [that men neither love You nor fear You chastely].73 The timor Dei [fear of God] characterizes a decisive moment of the experiential complex in which God becomes an object [gegenständlich wird].

This is supposed to rid us of the misunderstanding that the real experience consists in a certain act—of a theoretical or non-theoretical kind—or in a connection of parts of such acts. Rather, the experience of God in Augustine's sense is not to be found in an isolated act or in a certain moment of such an act, but in an experiential complex of the historical facticity of one's own life. This facticity is what is authentically original. From it, isolated modes of comportment can be separated out and, in being torn loose from it, they can lead to an empty conception of religiosity and theology.

The tendency of amare [to love] is a concern for oneself, the genuine amor sui [self-love] is love of oneself. Exactly this leads us into temptation. For this reason, it is precisely here that serious trouble (molestia) arises. Since the individual is entirely on his own, the greatest danger emerges, the danger that he forms his possible communal world—before which he puts on airs—from out of himself. From this latter consideration, Augustine comes to the “tremor cordis sui” [trembling of his heart].74 This is a phenomenon that is constitutive of the concern for oneself: the genuine timor [fear]. Slipping away from it is a self-removal from the “caste timere te” [chaste fearing of You], the pure fearing of God.

What now is the genuine “timor castus” [chaste fear] as opposed to the non-genuine “timor servilis” [servile fear]?

1. The timere in general and its possible motives.

2. Opposition: timor castus—timor servilis. (The How of the motivating affect.)

3. What sense does genuine fear have in connection with experiencing oneself? (That is, at once, in the basic experience of God.) How does God become an absolute object [absolut gegenstaändlich] in genuine fear? How is His objecthood determined on this basis?

(N.B. Our interpretation is still moving on a preliminary level: we do not yet have the authentic phenomenological concepts.)

Augustine begins with the concrete enactmental complex of fearing. He analyzes the non timere [not fearing] and its possible motives. He describes the mind of someone who claims to be without fear. In this, Augustine gains two motivational directions of not-fearing, and thus, the starting point of the division between timor castus [chaste fear] and timor servilis [servile fear]. He links timere with “dolere” [feeling pain] (dolere as a disposition of the mind, not pain but distress). In this, he begins with the non dolere or “sanitas” [health], of which different kinds are distinguished.

Enarrationes in Psalmos, ad Ps. 55, V. 4: non timeo [I do not fear]. Question as to the causa [cause]. The cause may be: 1. The praesumptio, spes, trust; 2. duritia (hardening): “multi enim nimia superbia nihil timent” [for many do not fear anything in excessive pride].75

“Aliud est sanitas corporis, aliud stupor corporis [dullness], aliud immortalitas corporis. Sanitas quidem perfecta, immortalitas est” [Something else is the health of the body, and yet something else the stupor of the body [dullness], and yet something else the immortality of the body. Indeed, perfect health is immortality].76 However, there is already health in this life, when we are not sick. What does this show?

There are three affectiones corporis [conditions of the body]: (1) sanitas [health], (2) stupor [stupor, dullness], (3) immortalitas [immortality].

1. “Sanitas aegritudinem non habet; sed tamen quando tangitur et molestatur, dolet” [Health does not have sickness, but it is painful when one is being touched and disturbed].77

2. “Stupor autem non dolet; amisit sensum doloris, tanto insensibilior, quanto pejor” [But stupor feels no pain; it has lost the sense of pain; the more insensitive, the worse it is].78

3. Immortalitas: it has no pain, since the possibility of corruptio [corruption, temptation] has been taken from it.79

Thus, with stupor and immortalitas, there is no pain, but this does not mean that the stupidus [stupefied, dull person] is immortalis [immortal]. On the contrary: the dolere of the healthy person is closer to immortality than is the dull person's lack of pain: “vicinior est immortalitati sanitas dolentis, quam stupor non sentientis” [the pain of the healthy one is closer to immortality than is the stupor of the insensitive one].80

At times, arrogant people are seen as braver than Jesus who says: my soul is sad until death. That cannot be. He who does not feel the pain because of his insensitivity has not put on immortality but has taken off sensitivity (“non immortalitate indutus, sed sensu exutus”81).

Do not keep your soul in a state without passion!—Genuine bravery requires the possibility of fear. The delectari [to be delighted] itself is eliminated in the one who is hardened, although, in this hardening itself, there is still a certain sense of delectari. Agreeableness with everybody is insensitivity, but not true tranquility.

Having no fear in trusting something is what is genuine; the fiducia [trust], as always-holding-on-to something (connection with spes [hope] and amor (caritas) [love (charity, love)].

The interpretation of two textual passages that (seemingly) contradict each other:

1. 1 John 4:18: “Timor non est in charitate” [There is no fear in love]. (There is no fear in authentic love.)

2. Psalms 18, V. 10: “Timor Domini castus, permanens in saeculum saeculi” [The fear of the Lord is chaste, enduring forever and ever]. (An observation of the interpretation of Scripture follows: a comparison of two passages with the consonance—consonantia—of two flutes.)

The contradiction is resolved by the distinction between two kinds of fear: timor castus [chaste fear] and non castus [non-chaste fear]. “Si enim adhuc propter poenas times Deum, nondum amas quem sic times. Non bona desideras, sed mala caves” [For if you as yet fear God because of punishment, you do not love whom you thus fear. You do not desire the good things, but you are afraid of the evil ones].82 Timor “non enim venit ex amore Dei, sed ex timore poenae” [This fear does not come from love of God, but from fear of punishment].83

But he who has begun to strive for the good for its own sake lives in pure fear. “Quis est timor castus? Ne amittas ipsa bona. Intendite. Aliud est timere Deum, ne mittat te in gehennam cum diabolo; aliud est timere Deum, ne resedat a te” [What is chaste fear? The fear that you lose the good things. Mark! It is one thing to fear God lest He cast you into hell with the devil, and another thing to fear God lest He forsake you].84 This fear does not have the direction of keeping something or someone at bay, but of pulling something or someone toward oneself. Timere separationem (est) amare veritatem [Fearing separation (is) loving the truth]. In this fear, the soul feels the majestas Dei [majesty of God].

Pure fear is connected to trust. Si times latronem [If you fear the robber], you hope for somebody else's help, not for help from the one who threatens you most of all (the robber). But if you fear God this way, to where should you turn? Vis ab illo fugere? Ad ipsum fuge! Vis fugere ab irato, fuge ad placatum! Placabis, si speras [You want to flee? Flee to Him! You want to flee from wrath, flee toward reconciliation! You will reconcile if you have hope].85

The first fear (timor servilis [servile fear]), the “fear of the world” (from out of the surrounding world and the communal world), is the anxiousness that grips and overwhelms a person.—By contrast, timor castus [chaste fear] is the “selfly fear” that is motivated in authentic hope, in the trust that is enlivened from out of itself. This fear forms itself within myself from out of the relation in which I experience the world, in connection with the life's concern for authentic self-experience. Nam si non times, aufert Deus, quid dedit [For if you do not fear, God carries off what He gave]. Precisely in fear, I keep a bonum [good thing].

8. The Being of the Self

[Concluding Part of Lecture]

“Vita” (life) is no mere word, no formal concept, but a structural complex which Augustine himself saw—without, however, yet achieving sufficient conceptual clarity. Today, this clarity has still not been attained, because Descartes moved the study of the self as a basic phenomenon in a different, falling direction. Modern philosophy in its entirety has not been able to rid itself of this.

Descartes blurred [verwässert] Augustine's thoughts. Self-certainty and the self-possession in the sense of Augustine are entirely different from the Cartesian evidence of the “cogito.”

Cf. De civitate Dei, lib. XI, c. 26 ff. Following the dogma of the trinity, Augustine considers the human being. (Cf. the treatise De trinitate.)

We find in ourselves an image of the highest trinity, for:

1. Sumus: we are (esse).

2. We know about ourselves, as such (nosse).

3. We love the knowledge about our own being (amare). These are the determinations of the authentic being of the self. “In his autem tribus […] nulla nos falsitas veri similis turbat” [Moreover, in these three (statements) (…) we are not confused by any falsity masquerading as truth].86 These are not objects; rather, without the stormy play of the imagination, that being which I know I love is most certain to me. Thus, it is certain: (1) that we love being, (2) that we love the nosse [knowing], (3) that we love the love itself in which we love (ipso amor quo amamus [the love itself that we love]).—“Ibi esse nostrum non habebit mortem, ibi nosse nostrum non habebit errorem, ibi amare nostrum non habebit offensionem” [Then our being will not possess death, then our knowledge will not possess error, then our loving will have no obstacle].87

Although we have a self-certainty of our being, we are nonetheless uncertain as to how long we have to live (quamdiu futurum sit [how long the future may be]), whether our being will not let go at some point.

The self-certainty must be interpreted from out of factical being; it is possible only from out of faith.

Methodologically, it is important that one may not view this evidence in isolation, which would constitute a falling.

The evidence of the cogito is present, but it must find its foundation in the factical. For every science ultimately rests in factical existence.

1. Enarrationes in Psalmos VII 9 (V. 10); PL 36, p. 103.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., p. 104.

4. De libero arbitrio II 13, 36; PL 32, p. 1260.

5. De civitate Dei, libri XXII, recogn. B. Dombart, Leipzig, 1877. XI 25; vol. 1, p. 496.

6. Ibid.

7. De doctrina Christiana I 4, 4; PL 34, p. 20.

8. De diversis quaestionibus XXX; PL 40, p. 19.

9. Epistulae LV 14, 26; PL 33, p. 217.

10. Enarrationes in Psalmos CXXXVI 22; PL 37, p. 1774.

11. Cf. Epistulae CCV, PL 33, p. 948.

12. “Nullus enim hominum est tanta justitia praeditus, cui non sit necessaria tentatio tribulationis” [For no human being is endowed with so great a justice that for him no temptation of tribulations would be necessary]. (Contra Faustum Manichaeum XXII 20; PL 42, p. 411).

13. Ibid.

14. Sermones II 3, 3; PL 38, p. 29.

15. Sermones CCCXLIV 1; PL 39, p. 1512.

*[Omissions in the lecture notes of Oskar Becker.]

16. [Editor's note: Due to the omissions in the notes, here is the Latin text of reference.] “Contendunt nobiscum quotidie tentationes, contendunt quotidie delectationes: etsi non consentiamus, tamen molestiam patimur, et contendimus, et magnum periculum est ne qui contendit vincatur; si autem non consentiendo vincamus, molestiam tamen patimur resistendo delectationibus” [Daily temptations strive with us, daily delights: although we do not consent, yet we suffer troubles, and strive, and great is the danger lest he who strives be conquered; and even if by not consenting we conquer, yet we suffer troubles in resisting delights]. (Enarrationes in Psalmos CXLVIII 4; PL 37, p. 1940.)

17. Enarrationes in Psalmos CXLIII 5; PL 37, p. 1858.

18. Sermones XXXII 11; PL 38, p. 200.

19. Enarrationes in Psalmos CXLIII 5; PL 37, p. 1859.

20. Ibid.

21. Enarrationes in Psalmos CXLIII 6; PL 37, p. 1859 f.

22. Ibid., p. 1860.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

* [Omission in the lecture notes.]

28. De doctrina christiana I 3, 3; PL 34, p. 20.

29. De doctrina christiana I 2, 2; PL 34, p. 19.

30. Cf. ibid., p. 20.

31. De doctrina Christiana I 22, 20; PL 34, p. 26.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. De doctrina Christiana I 22, 21; PL 34, p. 26.

35. Ibid., p. 27.

36. De doctrina christiana I 27, 28; PL 34, p. 29.

37. Ibid.

38. De doctrina christiana I 23, 22; PL 34, p. 27.

39. Ibid.

40. De doctrina christiana I 24, 24; PL 34, p. 27.

41. “Ne aut diligat quod non est diligendum, aut non diligat quod est diligendum, aut amplius diligat quod minus est diligendum, aut aeque diligat quod vel minus vel amplius diligendum est, aut minus vel amplius quod aeque diligendum est” [He neither loves what he ought not to love, nor fails to love what he ought to love, nor loves that more which ought to be loved less, nor loves that equally which ought to be loved either less or more, nor loves that less or more which ought to be loved equally]. (De doctrina Christiana I 27, 28; PL 34, p. 29.)

42. M. Luther, Disputatio Heidelbergae habita. 1518. D. Martin Luthers Werke (critical edition), vol. 1, Weimar, 1883, p. 354.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.

* [One word illegible.]

45. Confessiones VIII, 7; PL 32, p. 756.

46. De musica VI 2; PL 32, p. 1163.

47. Ibid.

48. De musica VI 3; PL 32, p. 1164.

49. Ibid.

50. De musica VI 4; PL 32, p. 1165.

51. De musica VI 1; PL 32, p. 1161 f.

52. Quaestionem Evangeliorum libri duo II 15; PL 35, p. 1339.

* [Two words illegible.]

53. Tractatus in Joannis Evangelium I 18; PL 35, p. 1388.

54. Tractatus in Joannis Evangelium I 19; PL 35, p. 1388.

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. Sermones LIII 10, 10; PL 38, p. 368.

58. Sermones LIII 10, 11; PL 38, p. 369.

59. Ibid.

60. Ibid.

61. Sermones LIII 11, 12; PL 38, p. 369.

62. Ibid.

63. Ibid.

64. Ibid.

65. Ibid.

66. Ibid.

67. Ibid., p. 370.

68. Ibid.

69. Ibid.

* [Three words illegible.]

70. ”Non frustra ergo crucem elegit, ubi te huic mundo crucifigeret. Nam latitudo est in cruce transversum lignum, ubi figuntur manus: propter bonorum operum significationem. Longitudo est in ea parte ligni, quae ab ipso transverso ad terram tendit. Ibi enim corpus crucifigitur, et quodam modo stat: et ipsa statio perseverantiam significat. Altitudo autem in illo ligno est, quod ab eodem transverso supernorum exspectatio. Ubi profundum, nisi in ea parte quae terrae difixa est. Occulta est enim gratia, et in abdito latet. Non videtur, sed inde eminet quod videtur” [Thus, it is not for nothing that he chose the cross on which to crucify you to this world. The breadth of the cross is given by the horizontal beam, where his hands are fixed: thus signifying good works. Length is given by that part of the vertical beam which extends from the crossbeam to the ground. That is where his body is crucified, and, so to speak, stands: and this standing signifies perseverance. Height is given by that part of the vertical beam which sticks up above the crossbeam to the head, so that it signifies expectation of the things that are above. Where do we have depth but in the part which is fixed in the ground. For grace is hidden, and remains concealed. It cannot be seen, but from it rises up what can be seen]. (Sermones LIII 15, 16; PL 38, p. 371 f.)

** [One word illegible.]

71. Tractates in Epistolam Ioannis ad Parthos IX 10; PL 35, p. 2052.

72. Cf. Tractatus in Epistolam Ioannis ad Parthos VIII 5; PL 35, p. 2038.

73. Confessiones X 36, 59; PL 32, p. 804.

74. “In his omnibus atque hujusmodi periculis et laboribus vides tremorem cordis mei” [In all these perils and travails, You see the trembling of my heart]. (Confessiones X 39, 64; PL 32, p. 806.)

75. Enarrationes in Psalmos LV 6; PL 35, p. 650.

76. Ibid.

77. Ibid.

78. Ibid., p. 650 f.

79. Cf. ibid., p. 651.

80. Ibid.

81. Ibid.

82. Tractatus in Epistolam Joannis ad Parthos IX 5; PL 35, p. 2048. [Augustine reads “timor castus” instead of the “timor sanctus” of the Vulgata. Editor's note.] Cf. Enarrationes in Psalmos XVIII 10; PL 36, p. 155.

83. Tractatus in Epistolam Joannis ad Parthos IX 5; PL 35, p. 2049.

84. Ibid.

85. [Editor's note: This passage is probably based on the following passages.] “Si vis ab illo fugere, ad ipsum fuge. Ad ipsum fuge confitendo, non ab ipso latendo: latere enim non potes, sed confiteri potes” [If you want to flee from Him, flee to Him. Flee to him by confessing, not from Him by hiding: you cannot hide, but you can confess]. (Tractatus in Epistolam Joannis ad Parthos VI 3; PL 35, p. 2021.) “Ille corde tuo interior est. Quocumque ergo fugeris, ibi est. Teipsum quo fugies? Nonne quocumque fugeris, te sequeris? Quando autem et teipso interior est, non est quo fugias a Deo irato, nisi ad Deum placatum: prorsus non est quo fugias. Vis fugere ab ipso? Fuge ad ipsum” [He is more interior to you than your heart. Therefore, wherever you flee, He is there. Where do you flee from yourself? Do you not follow yourself wherever you flee? So if He is more interior than you yourself, you cannot flee anywhere from an angry God except toward a reconciled God: it is precisely not where you may flee. Do you want to flee from Him? Flee toward Him]. (Enarrationes in Psalmos LXXIV 9; PL 36, p. 952 f.—Cf. Enarrationes in Psalmos XCIV 2; PL 37, p. 1217.)

86. De civitate Dei XI, 26; loc. cit., p. 497.

87. De civitate Dei XI, 28; loc. cit., p. 502.