Figure 14.3 The church of St Paul Outside the Walls, Rome

The focus of this chapter is the simple question of what happened in churches, and the temporal and spatial context of those activities. Chapter 2 includes material relevant to these themes in the third century (2.1, 2.4); this chapter pursues them through the fourth century and beyond. It begins with an example of a church calendar preserved on papyrus (14.1), before turning to the physical setting of church life – first as prescribed in a handbook on church organisation (14.2), and then as reflected in the plans of churches and in an artistic representation (14.3, 14.4, 14.5). An extract from a sermon provides valuable evidence on the character of preaching, and also on the important ritual of baptism (14.6), further reflected in an inscription (14.7) and an example of a baptismal font (14.8). A further extract from a sermon illustrates some of the problems that a preacher could encounter during a service (14.9), while two examples of hymns highlight another dimension of services (14.10, 14.11). Finally, the issue of pictures and images in churches is raised with reference to a textile wall-hanging and a painted icon (14.12).

Further reading: Krautheimer 1965; Dix 1945.

14.1 A calendar of church services: P. Oxy. 1357

The sixth-century papyrus document from which the following extract comes lists church services in the Egyptian town of Oxyrhynchus from October 535 to March 536. It is unlikely to be an exhaustive list of all the services during this period, its editors suggesting that it refers to those at which the bishop of Oxyrhynchus was (expected to be) present. It is unclear whether it is a list of forthcoming events or a record of services held, but it is of interest for the types of service held and the number of different churches (at least twenty-six) in a provincial town. Some churches are named after ‘principal’ saints (e.g., Mary, Peter, Paul), some after Egyptian saints, usually martyrs (e.g., Cosmas, Justus, Menas, Victor).

+ Notice of services (synaxeis) after the patriarch (papa) went downstream to Alexandria, as follows:

14th year of the indiction [535] Phaophi 23 [21 October] in the [Church] of Phoibammon, the Lord’s day [Sunday]

25 [23 October] in St Serenos’, day of repentance

30 [28 October] in the [Church] of the Martyrs, the Lord’s day

Hathur 3 [31 October] in the [Church] of Phoibammon, day of Epimachos

7 [4 November] in the Evangelist’s, the Lord’s day

12 [9 November] in St Michael’s, his day

13 [10 November] in the same

14 [11 November] in St Justus’, his day

15 [12 November] in St Menas’, his day

16 [13 November] in the same

17 [14 November] in St Justus’

<6 lines lost>

<Choiak> 7 [4 December] in St Victor’s

12 [9 December] in the [Church] of Anniane, the Lord’s day

15 [12 December] in St Kosmas’, day of Ision

19 [16 December] in the Evangelist’s, the Lord’s day

22 [19 December] in St Philoxenos’, his day

23 [20 December] in the same

24 [21 December] in the same

25 [22 December] likewise in the same

26 [23 December] in St Serenos’, the Lord’s day

27 [24 December] in the same

28 [25 December] in St Mary’s, the birth of Christ

29 [26 December] in the same

30 [27 December] in the same likewise

Tybi 1 [28 December] in St Peter’s, his day, and likewise in St Paul’s, his day

3 [30 December] in the [Church] of Phoibammon, the Lord’s day

11 [6 January] in the [Church] of Phoibammon, the epiphany of Christ . . .

14.2 Church layout and conduct of services: Apostolic Constitutions 2.57.1–9

The Apostolic Constitutions was a handbook on church organisation probably compiled in Syria in the late fourth century, and drawing heavily on a third-century work known as the Teaching of the Apostles (Didascalia Apostolorum). It provides guidance on the role of bishops, clergy and others involved in church ministry; here, it offers advice on the layout of the church building and the conduct of services.

(1) As for you, bishop, be holy and blameless, neither quarrelsome nor prone to anger nor harsh, but someone who knows how to edify, to discipline, and to teach; forbearing, gentle, mild, patient, someone who knows how to exhort and encourage, like a man of God. (2) When you gather together the church of God, like a helmsman of a great ship, command the congregation to behave with great discipline, instructing the deacons, like sailors, to assign the places to the brethren, like passengers, with great care and dignity. (3) And first, the church (oikos) should be oblong, facing the east with the sacristies on each side facing the east, resembling a ship. (4) Place the bishop’s throne in the middle, seat the presbyters each side of him, and the deacons should stand nearby, ready for action and properly attired, for they are like the sailors and those in charge of the rowers. Under their supervision, the layfolk should sit in the other part [of the church] in a very orderly and quiet manner; the women should sit separately and maintain silence. (5) The reader, standing in the middle on something raised, should read the books of Moses and Joshua the son of Nun, of the Judges and the Kings, of the Chronicles and the Return from Exile, then the books of Job and Solomon and the sixteen Prophets. (6) After every two readings, let another person sing the hymns of David and the people reply by singing the refrains. (7) After this, our Acts should be read and the letters of Paul, our fellow labourer, which he sent to the churches by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit; after this, a presbyter or deacon should read the Gospels which we, Matthew and John, have passed on to you, and which the fellow workers of Paul – Luke and Mark – received and bequeathed to you. (8) And while the Gospel is being read, all the presbyters and deacons and all the people should stand in complete silence; for it is written, ‘Be silent and hear, O Israel’ [Deut. 27.9], and again ‘But you, stand here and listen’ [Deut. 5.31]. (9) And the presbyters should encourage the people, one after another, but not all of them, and last of all the bishop, who is like the helmsman. . . .

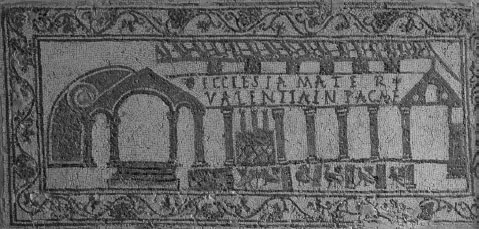

14.3 A basilica church: St Paul Outside the Walls, Rome

As church membership expanded beyond the capacity of house churches such as that at Dura-Europos (2.4), it became necessary to construct purpose-built structures able to hold large numbers. Both ideological and practical considerations ruled out anything derived from Roman religious architecture – ‘the temples of the old gods . . . had been designed to shelter an image, not to accommodate a congregation’ (Krautheimer 1965: 19). Instead, the model adopted was the basilica or secular audience hall used by Roman officials in the fourth century. Although many variations on this were possible, its essence was a nave with aisles and a rostrum at the far end on which the relevant official was seated. The churches built by Constantine in Rome and elsewhere followed this pattern, but another good example from later in the fourth century is the church of St Paul Outside the Walls, Rome (Figure 14.3), constructed on the initiative of the emperors Theodosius I, Valentinian II and Arcadius to provide for the shrine of St Paul a structure comparable to St Peter’s.

Further reading: Krautheimer 1965: 17–21, 63–4.

Figure 14.3 The church of St Paul Outside the Walls, Rome

Source: © Salzenberg/Simpson’s History of Architectural Development vol. II, C. Stewart, Pearson Education Ltd

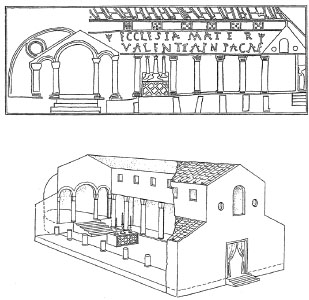

14.4 A provincial church: the Tabarka mosaic

Figure 14.4a Tomb mosaic of a basilica church, Tabarka, Tunisia

Source: German Archaeological Institute, Rome (DAI-ROM 61.535)

Figure 14b Line drawing of the tomb mosaic and reconstruction drawing of the basilica church, Tabarka, Tunisia

Source: From Archaeologia vol. 95 (1953): Fig. 28. By courtesy of the Society of Antiquaries of London

St Paul’s was a structure designed for use by some of the population of a large metropolis. By contrast, this mosaic (Figure 14.4, a and b) from a tomb at Tabarka in north Africa, conveys some idea of the appearance of a smaller provincial basilica church in the early fifth century, though it is not necessarily a depiction of an actual church, so much as a representation of an ideal. The line drawings accompanying it convey the essentials of the mosaic more clearly and how such a church might have looked in three dimensions. The inscription reads, ‘Mother church. Valentia, in peace’.

Further reading: Krautheimer 1965: 141–2.

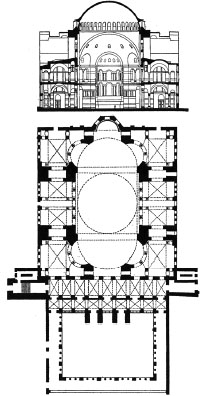

14.5 A domed church: Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

Following the devastation of the city centre of Constantinople during the Nika riot of 532, the emperor Justinian set about rebuilding the church of Holy Wisdom – Hagia Sophia – in magnificent style (Figure 14.5) (cf. 15.4). Although its design was based on that of the basilica church, it incorporated a feature that required great engineering skill – the addition of a dome. This feature had been used in smaller churches in recent decades, but it had not previously been attempted on anything like this scale. The effect is very impressive, creating a light, airy space that draws the eyes heavenward. For a contemporary description (including detail of the church’s lavish internal decoration), see Procopius Buildings 1.3.23ff.

Figure 14.5 Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

Source: © Salzenberg/Simpson’s History of Architectural Development vol. II, C. Stewart, Pearson Education Ltd

Further reading: Krautheimer 1965: ch. 9; Mainstone 1988.

14.6 Preaching and baptism: Ambrose On the Sacraments 1.4–5, 8–15

Baptism was one of the most important rituals in church life, the essential qualification which allowed a Christian to partake of the eucharist. Infant baptism was not unknown in Late Antiquity, but it seems to have been used primarily when children were close to death (Ferguson 1979). Although this will have been a common enough occurrence in a society with high mortality rates, most people will have been baptised as adults. This involved becoming a catechumen (literally ‘one who is instructed’) for a period of preparation. The baptism itself usually took place on the evening before Easter Sunday, and the sermons that comprise Ambrose’s work On the Sacraments were addressed to the newly baptised during the week after Easter. They are of interest not only for their description of the steps involved in baptism, but also as an example of preaching. There is good reason to think they are the verbatim text of what Ambrose said, copied down by someone in the congregation, and therefore not embellished subsequently. As will be evident, the style is very accessible and Ambrose uses a variety of techniques to ensure that his audience maintain their concentration and follow the argument. For the baptismal process, see Homes Dudden 1935: 336–42, Van der Meer 1961: ch. 12, Yarnold 1994; on Ambrose’s preaching, see Cramer 1993: ch. 2, Rousseau 1998 and Clark 2004: 87–8 (contra MacMullen 1989). Cf. also 5.3, 6.12, 15.3.

4. We have come to the font, you have entered, you have been anointed. Think about whom you have seen, reflect on what you have said, recall it carefully. A deacon [lit. ‘Levite’] meets you, a presbyter comes to you. You are anointed like an athlete of Christ, as if you are about to engage in a contest in this world. You have committed yourself to the exertions involved in your contest. Those who contend have what they hope for, for where there is a contest, there is a crown. You contend in the world, but you are crowned by Christ, and it is on account of the struggles in the world that you are crowned. For although your reward is in heaven, the earning of that reward takes place here.

5. When you were asked, ‘Do you renounce the devil and his works?’, how did you respond? ‘I renounce them.’ ‘Do you renounce the world and its lusts?’ How did you respond? ‘I renounce them.’ Recall what you said, and never forget the implications of the undertaking you have given. If you’ve given a written undertaking to someone, you are legally bound in order to receive their money; you are obligated and the money-lender can constrain you if you show reluctance. If you object, you go to a judge and there you’ll be convicted on the basis of your undertaking. . . .

8. So you have renounced the world, you have renounced the spirit of this age. Be alert! Those who owe money always keep in mind their undertaking. And you, who owe your faith to Christ, preserve that faith which is much more valuable than money. For faith is an eternal inheritance, whereas money is only temporary. So always remember what you promised: you will be more prudent. If you hold to your promise, you will also keep your undertaking.

9. Then you drew nearer, you saw the font, you saw the bishop near the font. I have no doubt that the same thought which occurred to Naaman crossed your mind, for even though he had been made clean, he still doubted at first. Why? I will tell you – listen.

10. You entered, you saw the water, you saw the bishop, you saw the deacon. In case someone perhaps says, ‘Is that all?’, it certainly is – where there is complete innocence, complete devotion, complete grace, complete holiness. You saw what you could see with physical eyes and with human perception; you didn’t see what was being done, but what could be seen. The things that cannot be seen are much greater than what can be seen, ‘because the things that can be seen are temporary, but the things that cannot be seen are eternal’ [2 Cor. 4.18].

11. Let us then say this first – keep in mind the promise I speak and demand its fulfilment. We marvel at the mysteries of the Jews given to our fathers, outstanding first in the antiquity of their sacraments, then in their holiness. But I promise you this, that the sacraments of the Christians are more divine and of greater antiquity than those of the Jews.

12. What is more extraordinary than the passage of the Jewish people through the sea (since we are talking about baptism at the moment)? Yet all the Jews who passed through died in the desert. But those who pass through this font, that is, from earthly things to heavenly – for this is a passage, and hence Easter (that is, Passover), a passing from sin to life, from guilt to grace, from impurity to holiness – those who pass through this font do not die but rise again.

13. So Naaman was a leper [2 Kgs. 5.1–14]. A slave girl said to his wife: ‘If my master wants to be clean, he should go to the land of Israel and find a man there who can free him from leprosy. The slave girl told her mistress, the wife told her husband, Naaman told the king of Syria; as one of his most highly valued men, the king sent him to the king of Israel. The king of Israel heard that he had been sent to him to heal his leprosy, and he tore his garments. Then the prophet Elisha sent word to him: ‘Why have you torn your garments, as though God does not have the power to heal leprosy?’ Send him to me.’ He sent him and the prophet said to the man when he arrived: ‘Go down into the Jordan, immerse yourself, and you will be healed.’

14. Naaman began to reflect on this and say to himself: ‘Is that all? I have come from Syria to the land of Judaea and I am told: ‘Go into the Jordan, immerse yourself, and you will be healed?’ As if there aren’t better rivers in my homeland!’ But his servants said to him: ‘Master, why not carry out the prophet’s instruction? Try it and see what happens.’ So he went into the Jordan, immersed himself, and emerged healthy.

15. So what does this mean? You saw the water, but it is not any water that heals, but water which has the grace of Christ. There is a difference between the element and its consecration, between the act (opus) and its efficacy (operatio). The act is carried out with water, but its efficacy comes from the Holy Spirit. The water does not heal unless the Holy Spirit has descended and consecrated that water. As you have read, when our Lord Jesus Christ established the pattern for baptism, he came to John and John said to him: ‘I ought to be baptised by you and you come to me.’ Christ replied to him: ‘Let it be so now, for it is fitting for us to fulfil all righteousness.’ [Matt. 3.14–15] See how all righteousness is established in baptism.

14.7 Baptism and burial: ILCV 1516

This inscription from Lyons, which has been dated on stylistic grounds to the fifth or sixth centuries (Le Blant 1856–65: 552–3), is of interest, first, for its implication that baptism was able to offset the perceived handicap of barbarian birth (line 3) (cf. Brown 1972: 54 n. 1), and second, for the way the bereaved parents are presented as coping with their grief (lines 7–8).

Here twin brothers, side by side, give their bodies to the

grave;

The soil has brought together these whom merit united.

Born of barbarian stock, but reborn from the baptismal font,

They give their spirits to heaven, they give their bodies to

the earth.

Sorrow has come to Sagile their father and his wife,

Who without doubt wished to predecease them.

But with Christ’s calming influence, great grief can be borne:

They are not childless – they have given gifts to God.

14.8 A baptistery: the Kélibia font

Figure 14.8 Baptismal font from Kélibia, Tunisia

Source: Musée du Bardo, Tunisia

This beautiful baptismal font, now in the Musée du Bardo in Tunisia, comes from the Church of St Felix near Kélibia, on the north African coast about 150 km east of Carthage, and dates from the sixth century (see Figure 14.8). The inscription can be read as follows (though there is debate about interpretation of the first half: Duval 1982: 54–8): ‘When the holy and most blessed Cyprian was bishop and priest, with the holy Adelfius presbyter of this [church] of the unity, Aquinius and his wife Juliana, with their children Villa and Deogratias placed this mosaic destined for the eternal water [of baptism]’. For the iconography employed, see Courtois 1955; Dunbabin 1978: 190. For the architecture of baptisteries and the range of possible shapes for fonts, see Davies 1962: ch. 1; Jensen 2005; and cf. 2.4.

14.9 Practical aspects of church services: Caesarius of Arles Sermon 78.1

This passage from a sermon contains a number of details of relevance to the conduct of church services in the west: the assumption that it was normal practice to stand during readings; the allusion to the fact that, in addition to passages from the Bible, martyr acts were sometimes read out (cf. Gaiffier 1954); and the common problem of clergy making themselves heard above the noise of congregational chatter (cf. Adkin 1985).

Moved by fatherly concern for those whose feet are in pain or who labour under some infirmity of body, I advised several days ago that when lengthy accounts of martrydoms (passiones prolixae) or some of the longer passages from Scripture are being read out, those who are unable to stand should humbly sit in silence and listen with attentive ears to what is being read. But now some of our daughters think that all of them, or at least the majority, ought to do this regularly, even those who are sound in body. For when the reading of the word of God begins, they want to lie down as if in their own little beds. How I wish they would only lie down, and silently receive the word of God with a thirsty heart, instead of also spending their time in idle gossip, so that they do not hear what is being preached and also prevent others from hearing. So I ask you, esteemed daughters, and I remind you with fatherly concern, that when readings are being recited or the word of God is being preached, no-one is to lie down on the ground unless perchance forced to by some very serious illness; and then, do not lie down, but rather sit and receive with attentive ears and a hungry heart that which is preached.

14.10 Hymns in the west: Ambrose of Milan Hymn 4 (‘God, creator of all things’)

Although Ambrose’s political interventions are the feature of his career which tends, understandably, to attract most attention (e.g., 6.5), another important legacy was his contribution to liturgy through his writing and use of hymns. Such was his impact in this sphere that his name literally became synonymous with ‘hymn’, often referred to as ambrosianum (e.g., Rule of Benedict 9.8). In a famous passage in his Confessions (9.7.15), Augustine describes Ambrose’s use of hymns during his conflict with the Arians of Milan in 386, concerning which Ambrose himself made the following significant observations: ‘They say that the people have been deceived by the lyrics of my hymns, and I certainly do not deny it, for there is nothing more powerful than elevated lyrics. For what is more powerful than confession of the Trinity, which is daily praised by the mouths of all the people? Everyone is eager to compete with one another in confessing the faith, for they know how to proclaim the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit when it is in verse. In this way those who could scarcely have been students have all become teachers’ (Letter 75a (21a).34; cf. McLynn 1994: 225–6; Moorhead 1999: 140–43; Liebeschuetz 2005: 124–73; Williams 2013).

Because of Ambrose’s fame as a hymn-writer, it became increasingly difficult with the passage of time to distinguish genuine compositions from those wrongly attributed to him, but there are at least some about whose authenticity there is no doubt, and one of these is translated below. (Augustine makes frequent reference to it in his Confessions, notably at 9.12.32, where he quotes the first two stanzas.) This hymn was written to be sung in the evening and the meaning of the lyrics is generally clear and self-explanatory, but the underlying thought warrants elucidation at a few points: in the third stanza, ‘the singers are regarded as having in the morning vowed to offer songs and prayers on being brought safely through the day. Now at evening, having obtained their petition, they acknowledge that the song and prayers are due’ (Walpole 1920: 47); and in the final line of the sixth stanza, ‘Ambrose seems to be thinking of the bodily warmth that accompanies sleep rising to overpower the soul and to set free the animal impulses’ (Walpole 1920: 48).

God, creator of all things,

Ruler of the heavens, who clothes

The day in glorious light,

And the night in the gift of sleep,

So that rest may restore tired limbs

To gainful work,

Relieve weary souls,

And release torturing anxieties –

As we sing our hymn, we offer

Thanks for the day now over,

And prayers for the oncoming night:

Help us fulfil our vow.

Let the depths of our hearts celebrate you,

Let resonant voices acclaim you,

Let pure love cherish you,

Let sober souls adore you,

So that when the deep gloom of night

Envelops the day,

Our faith can eschew the shadows,

And the night shine with faith.

Do not let our souls go to sleep,

Rather, may sin fall asleep.

Let faith, which refreshes the pure,

Temper the warmth of slumber.

Released from impure thoughts,

Let the depths of our hearts dream of you,

Let not fear, by a trick of the jealous enemy,

Rouse us from our rest.

We ask Christ and the Father,

And the Spirit of Christ and the Father,

One being, powerful in everything -

Succour us who pray to you, Trinity.

14.11 Hymns in the east: Romanos the Melode Hymn 49.1–4, 15–18 (Pentecost)

Ambrose was only one of a number of fine Christian hymn writers during Late Antiquity. The eastern half of the empire produced its fair share, of whom the most famous was Romanos the Melode, active during the reign of Justinian. His hymns, of which more than fifty survive, are known as kontakia. Thought to be influenced by Syriac hymn-writing (Romanos was a native of Syrian Emesa), distinctive features of the kontakion include a refrain at the end of each stanza linking it back to the Introduction and the use of ‘bold imagery and vivid, almost theatrical, dialogue that dramatically recreates the scriptural texts set in the liturgical calendar’ (Jeffreys 1991: 1148). The following extracts from his hymn for Pentecost illustrate these features, while also containing (in the final stanzas) an interesting expression of hostility towards classical (pagan) education, which perhaps reflects the generally rigorist attitude towards paganism that characterised Justinian’s reign. It has been argued that the particular names singled out for denigration in Stanza 17 were carefully chosen to provide comprehensive coverage of the traditional classical syllabus – the trivium, comprising grammar (Homer), rhetoric (Demosthenes), and dialectic (Plato), and the quadrivium, comprising geometry, arithmetic and music (Pythagoras) and astronomy (Aratos) (Grosdidier de Matons 1981: 207 n. 2).

Further reading: Carpenter 1970: Introduction; Topping 1976 (though Grosdidier de Matons (1981: 177–8, 203 n. 2) disagrees with Topping about linking the hymn to 529 and Justinian’s closing of the Athenian Academy).

(Introduction)

When he came down and threw the languages (glōssas) into

confusion,

The Most High divided the nations.

When he distributed the tongues (glōssas) of fire,

He called all people to unity,

And united in voice we glorify the Spirit all-holy.

(1)

Give your servants speedy and steadfast comfort, Jesus,

In the discouragement of our spirits.

Do not separate yourself from our souls in their afflictions,

Do not distance yourself from our hearts in their anxieties,

But come quickly to us always.

Draw near to us, draw near, you who are everywhere!

Just as you were always with the apostles,

So also unite yourself with those who long for you, Compassionate

One,

So that, joined with you, we may sing hymns and glorify

The Spirit all-holy.

(2)

You were not separated from your disciples, Saviour, when you

journeyed back to heaven;

For when you reached on high, you embraced the world below.

For no place is separated from you, whom no space can contain.

And if it comes into existence, it is destroyed and disappears,

And undergoes the fate of Sodom.

For it is you who maintains the universe, filling everything.

So the apostles had you in their souls;

Therefore they came down from the Mount of Olives, after your

ascension,

Dancing and singing and glorifying

The Spirit all-holy.

(3)

The eleven disciples returned joyfully from the Mount of Olives.

For Luke the priest writes thus:

They returned to Jerusalem,

They ascended to the upper room where they were staying,

And on entering, they sat down,

Peter and the other disciples.

Cephas [Peter], as their leader, said to them,

‘We who are partakers of the kingdom – let us lift our hearts

Towards him who spoke this promise, “I will send you

The Spirit all-holy.”’

(4)

Then after saying this to the apostles, Peter urged them to pray,

And standing in the midst, he cried out,

‘Let us entreat on bended knee, let us implore,

Let us make this room a church,

For it is one and is becoming one.

Let us weep and cry out to God,

“Send us your wonderful Spirit,

So that he may guide all people to the land of righteousness

Which you have prepared for those who worship and glorify

The Spirit all-holy!”’

[Stanzas 5–14 recount the events of the Day of Pentecost]

(15)

But when those who had come there from everywhere saw them

speaking in all the languages,

They were astonished and cried out, ‘What does this mean?

The apostles are Galileans,

So how have they just now become, as we look on,

Fellow-countrymen of all nations?

When did Peter Cephas visit Egypt?

When did Andrew live in Mesopotamia?

How did the sons of Zebedee see Pamphylia?

How are we to make sense of this? What should we say? It is entirely as desired by

The Spirit all-holy.’

(16)

Those who until recently were fishermen have now become learned

men (sophistai),

Now they are gifted speakers (rhētores), clearly comprehensible,

Who previously dwelt by the shores of lakes.

Those who started off stitching nets

Now unravel the snares of clever speakers and discredit them in

their unadorned speech.

For they speak the Word instead of a cloud of words,

They proclaim the one God, not one god among many.

They worship the One because he is one, the incomprehensible

Father,

The Son of the same nature, and, inseparable from them and like

them,

The Spirit all-holy.

(17)

Has it not been granted to them to prevail over everyone through

the languages they speak?

So why are the fools outside [the church] spoiling for a fight?

Why do the Hellenes bluster and drone on?

Why do they allow themselves to be deluded by the thrice-accursed

Aratos (Araton ton triskataraton)?

Why do they go astray in the company of Plato (planōntai pros

Platōna)?

Why are they fond of the feeble Demosthenes?

Why do they not realise that Homer is an idle dreamer?

Why do they babble on about Pythagoras who has rightly been

silenced?

Why do they not run with faith to those to whom has been revealed

The Spirit all-holy?

(18)

Let us praise, brothers, the tongues of the disciples, for it was

not with clever speech,

But with divine power that they caught every person.

They took his cross as a fishing rod, and they used words as a

line,

And they fished the world.

They had the Word for a sharp hook,

As bait they had

The flesh of the Lord of everything, not catching to kill,

But luring to life those who worship and glorify

The Spirit all-holy.

14.12 The church and images: a textile representation of Mary and a painting of Peter

The attitude of church authorities towards the use of Christian images in the third and fourth centuries was generally negative – no doubt as a result of the role of statues and other representations of the gods in pagan cults. In the early fourth century, e.g., a church council issued the following pronouncement: ‘It was decided that there should be no pictures in church, for whatever is worshipped and reverenced might be depicted on the walls’ (Council of Elvira, Canon 36; cf. Eusebius Letter to Constantia and Epiphanius Letters [translations in Mango 1986: 16–18, 41–3]). Yet it is apparent from the Dura baptistery (2.4) and the Roman catacombs that, in practice, decoration of Christian structures did occur, and by the latter half of the fourth century, artistic representations of Biblical themes were beginning to be accepted as having educative value, especially for Christians who were illiterate (e.g., Paulinus of Nola Poem 27.511–48). This, however, is still some distance from actual reverence for images, which becomes apparent during the sixth century and was to prove so controversial in the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries.

Figure 14.12a (178 x 110 cm) is a representation of Mary flanked by the archangels Michael and Gabriel, with Christ as a child in her lap and Christ as king above; the scene is surrounded by a decorative border with busts of the twelve apostles. The picture is woven in wool with a predominance of rich blues and reds, and was probably produced in sixth-century Egypt. Mary’s special status developed particularly in the fifth century. One of the basic tenets of the Monophysite movement (which was especially strong in Egypt) was that Mary was the Theotokos (‘the mother of God’), rather than the Christotokos (‘the mother of Christ’) – a distinction that emphasised Christ’s essential divinity. In the late sixth century, Mary also became a particular object of devotion in Constantinople. On the tapestry, see Shepherd 1969; Weitzmann 1978: 46–7 (including colour photograph); on reverence for Mary, see Cameron 1978.

Figure 14.12b (92 x 53 cm) is an encaustic painting of the apostle Peter preserved in St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai, though it is thought to have been executed in Constantinople, probably in the late sixth or early seventh century. It is of particular interest for the way in which it imitates late Roman consular diptychs (small representations of the office-holder carved in ivory), though with important differences: where the consul typically holds a sceptre of authority, Peter holds a staff topped with a cross, and where the consul holds the napkin to start the celebratory chariot races, Peter holds the keys of the kingdom. Above him in the three medallions where one would expect the emperor, empress and co-consul, there are represenations of Christ, Mary and perhaps St John. On the painting, see Weitzmann 1978: 55–5 (including colour photograph); on icons more generally, see Cameron 1992.

Figure 14.12a Icon of the Virgin. Egypt, Byzantine period, sixth century. Tapestry weave, wool, 178 x 110 cm

Source: © The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1999, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Bequest, 1967.144

Figure 14.12b Encaustic icon of St Peter. 92 × 53 cm

Source: Reproduced through the courtesy of the Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expedition to Mount Sinai