Cover of The Gender Book, a colorful short book made to educate and entertain.

Holiday Simmons and Fresh! White

THERE IS NO ONE WAY TO BE TRANSGENDER. We are teachers, scientists, business leaders, ranchers, firefighters, sex workers, weight lifters, students, activists, and artists. We are young and old, rich and poor, gay, straight, bisexual, and queer. We are every different race and we live in every country in the world. We have families and friends who listen to us and who work to understand our stories and our lives. We have allies who stand up for us and our communities and work with us to make the world a more accepting place. We appreciate their help immensely.

As transgender and gender nonconforming people (or trans people, for short), we have many different ways of understanding our gender identity—our inner sense of being male, female, both, or neither. Some of us were born knowing that something was different about us. Others of us slowly, over time, began to feel that we were not our full selves in the gender roles we had been given. Our many different ways of identifying and describing ourselves differ based on our backgrounds, where we live, who we spend time with, and even media influences.

Cover of The Gender Book, a colorful short book made to educate and entertain.

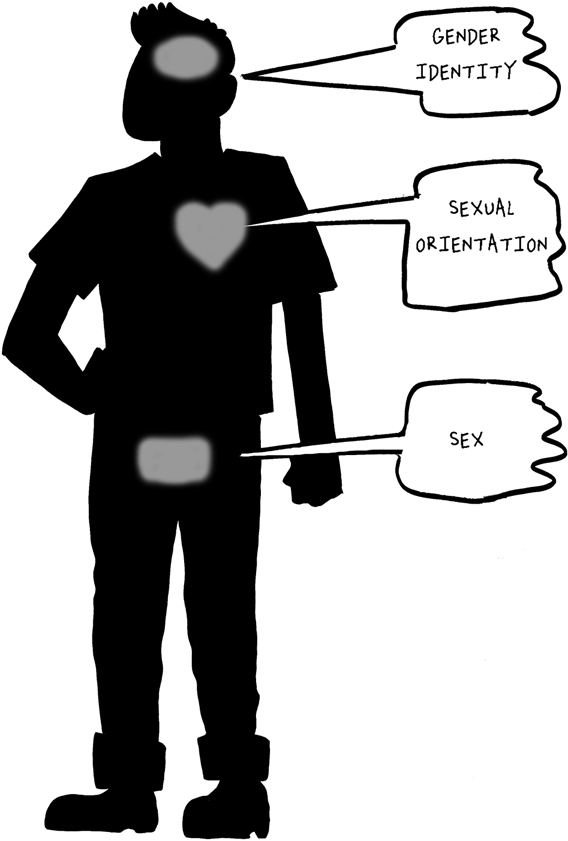

Identity, orientation, and sex (kd diamond).

We find ourselves frequently creating and changing the terminology that best fits or describes who we are. These changes can, at times, create complications inside and outside our communities. Factors such as culture, location, and class sometimes mean we do not all agree. But our communities work to honor and respect everyone’s self-identification.

“I use the terms trans guy, trans-masculine, queer, dyke. In the past I used the terms FTM and transgender in talking to others, as these were the terms available to me. I thought that using these more familiar and linear terms would make it easier for others to understand ‘what I am.’ I used to feel more of a need and pressure to fit a familiar and simple narrative of going from one point to another.”*

“I am an ally of minority communities within the transgender community: two of my friends are disabled and transgender identified. I have developed an awareness of people’s intersecting identities, and the privileges I hold compared to others.”

Sex and gender have only recently begun to be thought of as separate concepts. Our sex is generally considered to be based on the physical characteristics of our body at birth and has traditionally been thought of as biological. In comparison, gender is thought of as related to our social interactions and the roles we take on. It is an oversimplification to think of sex as biological and gender as social, but these terms can help us to communicate about what our bodies look like in comparison to how we feel.

For a fun, interactive way to spend time thinking about your gender, find a copy of My Gender Workbook: How to Become a Real Man, a Real Woman, or Something Else Entirely by Kate Bornstein.

“I don’t like to use terms like ‘Bio-Female/Male’ or ‘Female/Male-Bodied’ because I don’t think they account for Intersex folks. They also refer to the bogus medicalization of the gender binary, which I think gives the binary more power. I want to use words that refer to the social construction of the gender binary, like ‘Read as Female’ and ‘Female Assigned at Birth’ because it makes it clear that these are descriptions forced upon me and they don’t have any real standing.”

“Genderqueer, genderbender, boi. I don’t really see myself as one sex over the other. I am biologically female, although I have had FTM top surgery. I am not on testosterone, as I don’t feel like being labeled male would make me feel closer to what I feel I am. And what am I? Something in between.”

Most of the time, a person’s sex and gender are congruent. However, those of us who identify as trans generally experience gender dissonance or gender incongruence. We find that our affirmed gender doesn’t match our assigned sex or societal expectations.

Colt Keo-Meier, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, researcher, educator, and out trans man in Texas.

Many people have tried to count the number of transgender people worldwide. Unfortunately, all of our methods have flaws. Gender clinics may only count people who have received hormones and multiple surgical treatments. Some people choose not to be counted in research, for instance, if they have a transgender history but do not identify as transgender (Meier & Labuski, 2013).

However, it is still important to attempt to determine the numbers because basic demographic information on minority populations informs public policy, health care, legal discourse, and education (Winters & Conway, 2011). Many important and influential decisions are made based on how many of us there are. The government could spend more money on grants that benefit our community, and insurance companies could decide to cover trans-related medical care if we were able to show that there are large numbers of trans people. The best estimates we have right now identify 15 million trans people worldwide (Winter & Conway, 2011) and 700, 000 in the United States (Gates, 2011). This translates to 0.3% of the US population, or about 1 in every 333 people. Historically, estimates have generally stated that there are many more trans women than trans men, and some theories have suggested that people who are assigned female at birth transition less because there is greater social acceptance for maneuvering with more masculine expression. More recently, experts have estimated that there are probably about the same number of trans men and women.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Gates, G. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Retrieved January 2013, from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf

Meier, S. C., & Labuski, C. (2013). The demographics of the transgender population. In A. Baumle (Eds.), The international handbook on the demography of sexuality (pp. 289–327). New York, NY: Springer Press.

Winters, S., & Conway, L. (2011). How many trans* people are there? A 2011 update incorporating new data. Retrieved December 2013, from http://web.hku.hk/~sjwinter/TransgenderASIA/paper-how-many-trans-people-are-there.htm

We choose our gender expression or gender presentation through our clothing, our hairstyles, and our behaviors, which help us present ourselves to the world as we want to be seen.

Transgender and trans are often referred to as umbrella terms because they can include many different identities. More recently, the terms trans* read as “trans star” and TGNC, an acronym for trans and gender nonconforming, are being used more broadly to signify that there are numerous identities within transgender communities. Some people who others refer to as transgender do not identify with the term transgender at all.

Dallas Denny and Jamison Green comment on the use of transgender as a noun: “Transgender is increasingly used as a noun to describe individuals generically—such as ‘Samantha is a transgender, ’ not ‘a transgender woman’ or ‘a transgender person’—as though their variance from gender norms was their most significant feature. Though some of the main journalism guides support this, we feel the word transgender should modify a noun rather than becoming one. Giving it some grammatical context and variability as an adjective helps ensure this. When trans people are described only as ‘transgenders, ’ we feel the term easily dehumanizes us.”

“I tend to prefer MTF. I do not consider ‘transgendered’ to be a natural state. It’s more a bridge to cross as soon as possible in order to be female.”

“I’m a man, so I’d like people to refer to me as one. I find it offensive to be described as ‘transgender, ’ first because I’m not sure what the word means or that anyone knows what it means; second, because there’s nothing particularly transgressive or edgy or revolutionary about my gender. I’m a dude. That I was assigned female at birth is inconvenient for me, but has no greater social import.”

Andrés Ignacio Rivera Duarte, 42 años, Profesor, Transexual, Activista Defensor de los Derechos Humanos, un hombre con vagina.

Transsexual men have some advantages in belonging to a “machista” society like the one in Chile, because that society values masculinity. Being a lesbian woman is not criticized much or discriminated against, because we are more accepted as “marimachos” or “mujeres amachadas,” and that allows some of us to study and finish school. There is some discrimination, but it is not as aggressive and also not as violent or life-threatening as violence toward feminine people.

The reality for transsexual women is much more difficult. They are treated as “maricones.” In school they are discriminated against, and face physical aggression and mocking. Often, trans women quit or are forced out of school which limits their options to qualify for jobs. Then, many of them turn to prostitution as the only way to make a living. This leaves them exposed to the cruelty of the streets and extremely vulnerable to HIV, alcoholism, and drug addiction.

The realities for transsexual men and transsexual women are very different. In the eyes of mainstream Chilean society, there is a strong belief that transsexual women are “putas” and “maricones vestidos de mujer.” Transsexual men are much more likely to be viewed as successful and to be considered people with basic or equal rights.

There are many ways we may choose to identify ourselves within trans communities. We may call ourselves trans men or female-to-male (FTM/F2M) transgender people if we were assigned female at birth (AFAB) and view ourselves as male. We may see ourselves as trans women or male-to-female (MTF/M2F) transgender people if we were assigned male at birth (AMAB) and see ourselves as female. Those of us who are younger may identify as trans guys/boys or trans girls instead of trans men or women.

Check out these Web sites for trans men: transguys.com, trans-man.org, thetransitionalmale.com.

“Trans, transgender, transsexual, MTF, girl, woman. I use those terms because they are more empowering than any of the other terms. When I use them I feel that I’ve had enough shame in my life. These do not impart shame.”

“I don’t like transman written all as one word; this to me suggests a transman is something different from a man, which is not how I identify. I prefer trans man as simply descriptive, and no more emasculating than describing someone as a Jewish man or a gay man. I’m also not keen on when people refer to FTMs as female-bodied (or MTFs as male-bodied) since I feel the process of transition makes that very inaccurate very quickly (ridiculous to refer to someone with a t-pumped body and a beard as ‘female-bodied’).”

The project I AM: Trans People Speak is designed to show the diversity of backgrounds and experiences that exist within trans communities. Check out the Web site for stories, photos, and videos from transgender people across the United States.

Those people whose sex and gender identity match may be referred to as cisgender, as cis in Latin means “on the same side,” while trans means “on the opposite side.” As trans people, we have many cisgender allies—those who show their support for the concerns, needs, and rights of trans people, even though they may not personally face the same issues. Many of us prefer the term cisgender to other terms like biological male/female or natural male/female because those terms make it sound as if there is something more real about being cisgender than transgender. Others of us do not mind these terms and use shorthand versions like bio girl or genetic girl (g-girl) to refer to cisgender women, and t-girl to refer to trans women.

Misster Raju Rage is a community organizer, artist, and writer who prefers to be undefined.

What is feminine? What is masculine? I field these questions a lot. I often refuse to answer, which tends to force people to consider gender as a fluid, rather than as a fixed, state. It also encourages them to question more deeply than they have before—which in turn pushes them beyond what they have been told and beyond the answers they expect.

People also ask this question of me to derive my gender status, in order to pin it down. I am ambiguous as male or as female, even though I do not consider myself strictly either and would define myself as transgender. I have taken to just saying I am “undefined” or that “I don’t know or care” when people ask me my gender.

I have felt comfortable with both masculinity and femininity and uncomfortable with both at different times. I allow myself both expressions and in different combinations depending on many factors, such as environment, mood, or safety. I don’t restrict my behavior or activities based on whether they are considered “masculine” or “feminine,” so I generally do not get caught up in the distinction. I often cannot differentiate between them—both are enmeshed, and both are in me.

When I “drag up” as my alter ego “Lola,” it is an expression of both my femininity and masculinity—my femme masculinity. “Lola” is a statement of the fact that I do not see myself as a solely masculine trans guy but that I am femme, even though I consider myself male and use male pronouns. When I dress up as Lola, I feel I possess a strength that I find truly feminine; and that is also a culturally Indian femininity, rather than a Western femininity.

My family cannot fully accept that I am transgender. They have been socialized in the dominant Western world. More dominant cultures tend to dictate what is acceptable in terms of defining gender, so my family does not understand that I want to be considered male, with masculine pronouns, because they see my femininity (which I do not conceal).

But in my culture, and in many others, many men are effeminate. In my culture, it is common for gender variation (with hijras and kothis, for example) to exist within and alongside broader cultures. If we open our eyes, we see that people are comprised of many different shapes and sizes.

For this reason I make a political statement to not define what is masculine or feminine. That can only be answered personally by each and every individual. For me, being feminine is looking into my heritage of strong Indian female role models who are not afraid to express who they are. For me, masculinity means being different from the negative male role models I have had in my life, making a stand to reject misogyny and introduce feminism, and embracing the idea of brother/sisterhood.

Sex is as variable as gender. Some of us are born with bodies that do not fit neatly into what we expect of male and female bodies, and we may refer to ourselves as intersex or may identify with the idea that we have a disorder of sex development (DSD), although for many people, the idea of being labeled with a disorder or condition is disparaging. An older term for intersex people is hermaphrodite, but few people find this respectful. Many of us understand intersexuality as a normal variation of human existence.

While many intersex people do not consider themselves part of trans communities, some do. Intersex is sometimes represented as the “I” in LBGTQI. Some intersex people take hormones or have surgeries, either to see themselves as more fully male or female, or to correct childhood surgeries.

“I am post-op MTF. . . From a medical stand point I am FTMTF due to the fact I was born intersex. . . I was not born with a proper penis so one was constructed when I was younger. . . The penis was never finished and I told [my doctor] I didn’t want him to finish it.”

Some trans people identify as intersex or find that this can be a way to explain ourselves to others. However, it is important to respect the identities and experiences of intersex people when using this word. Over time, we have built many alliances between trans and intersex people. However, the needs and struggles of the two groups can often be different and they should not be generalized.

When we begin to identify with a particular gender, we often go through a process of coming out, when we acknowledge to ourselves and our communities that we wish to live our lives as a gender different than the one we were assigned at birth.

As trans people, many of us choose to transition, to physically alter our bodies and our behaviors to align our gender identity with our gender presentation. Some of us take hormones or have surgeries. Some of us wish we could afford surgeries. Others of us do not want to take hormones or have surgeries, but we dress and act in ways that affirm our gender identity.

Those of us who have surgeries may want top surgery, which changes our chests, or bottom surgery, which changes our genitals. There are also numerous other types of surgery that have the potential to change our gender appearance, including facial surgery and tracheal surgery (to remove the Adam’s apple).

Online guides to all things transgender include Transsexual Road Map (tsroadmap.com), The Transgender Guide (tgguide.com), T-Vox (t-vox.org), TG Forum (tgforum.com), Susan’s Place (susans.org), Lynn’s Place (tglynnsplace.com), and Laura’s Playground (lauras-playground.com).

“The incongruence between my mental self image and physical body has become increasingly distressful for me, so last year, after three years of therapy and two of binding my breasts, I decided to undergo a double mastectomy and male chest reconstruction surgery. I feel much better now that I no longer have breasts. I walk taller, I feel more comfortable going about my daily activities, and I can take my shirt off in front of my lover without feeling awkward now. Since deciding on surgically altering my body to masculinize it, I’ve begun to identify as transsexual.”

Some of us identify as transsexual, or TS. For many of us, identifying as transsexual means that we would like to or have had some variation of sex reassignment surgery (SRS) or gender-affirming surgery (GAS), although this is not true of everyone who identifies as transsexual.

“Transsexual. I’m taking hormones now. That’s what I’m called because of the hormones. There are stages I’ve been going through.”

“I hate transsexual. The word really seems too closely linked to sexual behavior and completely misses the concept of gender identity.”

The distinction between various trans people is not whether we have had certain kinds of body modifications but how we identify. Some of us have not had chest reconstruction surgery, hormones, or genital surgery, either for financial reasons or because we are at peace with our bodies as they are, but still identify as women or men. Some of us may choose to undergo medical or surgical interventions, without seeing ourselves as exclusively male or female.

Sometimes trans community members make judgments about other community members regarding whether they are authentically trans.

“Nobody in the lesbian community ever said I wasn’t ‘lesbian enough’ whereas I was told early in my coming out that I wasn’t ‘trans-enough.’”

“I’d prefer if I was just called by my name, in whatever fashion they choose, the feminine or the androgynous version. For me, the way someone may believe I am is not necessarily how I see myself. And as a Black female, the identity I encompass as of present is so out of the box that this community doesn’t know how to categorize me. So I’ve learned to accept that the only opinion of who I am that I care about is my own and the people I trust.”

Transgender Versus Transgendered

“Many people discourage use of the term transgendered. However, a number of well-known writers of transgender or transsexual experience use both transgender and transgendered, notably Kate Bornstein, Matt Kailey, and Susan Stryker.

Being transgendered is commonly compared to being ‘deafed’—but it is not the same. All people are ‘gendered’ by our own or others’ perception of us in relation to the binary assumptions about sex and gender that surround us. We have gender, and we are gendered by the world around us; and therefore, we can be transgendered. Deaf people, who have deafness, may have been deafened. We realize that no one person or group can control the evolution of language, and we think that’s good!” Dallas Denny and Jamison Green

Some trans people use the term transgendered, while others find it offensive.

Some people believe that the term transgender should be used to describe only those who are legally or medically transitioning. This stance may come from the idea that those who transition in these ways face more discrimination and harassment, and have therefore earned their status as trans or proved that they are dedicated to the identity. However, those of us who have not transitioned in these ways may still face very difficult situations. Gender policing can be harmful and divisive.

“I really prefer ‘transgendered’. . . as a descriptor, because it implies movement and fluidity.”

“I hate when people say ‘transgendered, ’ because it sounds like a disease, and it’s dated.”

While some of us may continue to live our lives as openly trans, some of us who “pass,” or have our male or female gender presentation correctly read by others around us, choose to live stealth. This means that few, if any, of those around us know that we are transgender. Living stealth may be a matter of safety or privacy for some of us; for others, it is a matter of what feels natural and makes us happy. For most of us, our lives are combinations of living openly, passing, and being stealth depending on the context or situation.

“I live full stealth, I do not advertise my medical history or genital configuration. I am one of the fortunate few that is able to blend in well with other women. It works for me and that’s how I live my life. Where I live, there are a LOT of ignorant bigots and it’s not at all safe to be out and open about such things as this. I have a few cisgendered friends that know of my past but they treat me as 100% female and nothing less. So I do not like the tags because when the general public hears those tags they think pervert, freak, sicko, etc. Those tags are all heavy, negative labels the people use to separate, isolate, insult and harm us with.”

“I strongly prefer simple female pronouns/references. I don’t believe in ‘stealth’ (for myself) and I don’t hide from my past, but I look at my gender history the way someone would look at having spent their childhood in Poland or Madagascar or on Army bases or something—an important part of my development, sure—something that may make me a bit of a stranger to these shores sometimes, but not the defining experience of my life.”

Some of us do not identify as trans at all. Instead, we may identify as simply male or female. We may refer to ourselves as women or men of trans experience, or as affirmed males or affirmed females.

“Gay man of trans experience. I use this because being trans describes an experience I’ve had, not an identity.”

“I usually just call myself a man. In appropriate contexts, I call myself a trans or transsexual man, or a man of trans experience. I used to call myself ‘FTM, ’ but it doesn’t feel right anymore—maybe I grew out of it. I also call myself queer, nelly, bear, and fag.”

A common misconception about trans people is that we are all gay or lesbian. While we often form coalitions of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, gender and sexuality are two separate things. Our gender identity is our own sense of whether we understand ourselves as men, women, or something else. The phrase sexual orientation is used to describe the gender or genders of the people to whom we are attracted. As trans people, we may be gay, straight, bisexual (attracted to both men and women), pansexual (attracted to all genders), or asexual (not sexually attracted to anyone). Our sexual preferences may depend on many factors other than the genders of the people we are attracted to. Like everyone, we may consider class, education, spiritual practices, body shape or size, and dominant or submissive attributes in picking partners.

“My preference is for people to use the same terms they would use for cissexual men. I particularly don’t like it when people assume that my being transexual is what makes me queer. I’m queer because I’m a man who is attracted to men and because I am a part of queer communities, not because I was assigned the wrong sex at birth, or because my brain sex was incongruent with my body sex.”

“I have used, in various contexts, the terms trans, transgender, transsexual and MTF to describe myself. Over time I tend to just use transgender or trans simply because it’s easier for people who don’t understand the difference to understand. I also found that the use of transsexual often led to the wrong impression that somehow what I’m going through is sexually related.”

LGBT is an acronym that is expanding considerably and has many current permutations. LGBTQ adds either questioning or queer to the end. Questioning refers to those people who are not yet sure about their sexuality or gender identity. Another permutation of LGBT is LGBTQIA (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Allies). These acronyms can become very long. For example, LGBTT2QQAAIIP stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Transexual, Two-Spirit, Queer, Questioning, Asexual, Allies, Intersex, Intergender, and Pansexual.

Peter Cava is the Lynn-Wold-Schmidt Peace Studies Fellow at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

As trans politics have gained greater visibility, many people who do not self-identify as trans have been wondering if and how they have a stake in these politics. In a 2013 column, Dan Solomon addressed this question. He began by drawing a clear line between himself and trans people: “I’m not transgender....I am a dude who is straight and cisgender (that is, someone whose gender identity matches their biology).” He recognized that this difference afforded him privilege: “Everyone else seems to treat us [cis people] pretty well.” Nevertheless, he believed that cis people should care about trans politics for two reasons. The first is compassion: “The fact that transgender people live under a constant threat of violence should stir you.” The second is self-interest: Solomon imagined that if trans people were to remain preoccupied with “defending their right to exist,” then a trans person would miss an opportunity to invent a “fucking flying car” that cis people could enjoy. Therefore, cis people could benefit from trans rights.

By appealing to both compassion and self-interest, Solomon made a valuable contribution to a conversation about trans allyship. We can take this conversation further by rethinking the cis-trans distinction. What would make a person’s gender identity match their biology? For example, by this definition, could a cis woman have a dapper moustache, or a cis man, dainty ears? And what about gender expression? Is someone with a male identity, male biology (whatever that means), and a flirty cocktail dress, cis? No—no one is cis in all ways always (Enke, 2012). Rather, everyone is on the blurry and beautiful rainbow of diversity that gender theorists C. L. Cole and Shannon L. C. Cate have called the transgender continuum.

The trans continuum can inform the conversation about trans allyship in several ways. First, what does the trans continuum mean for cis identity? The “cis” identity label, like all such labels, is provisional. It can serve as a help or a hindrance, depending on the context. Second, what does the trans continuum mean for cis privilege? Cis privilege is not the exclusive property of a cis majority; rather, all people experience cis privilege when our gendered embodiments and expressions are perceived as more congruous than someone else’s (see Enke, 2012, pp. 67–68, 76). Therefore, all of us can practice trans allyship by dismantling our cis privilege. Third, what does the trans continuum mean for trans allies? Allies have a stake in trans politics not only because allies have compassion, and not only because allies want fucking flying cars, but also because allies are part of the rainbow. And finally, what does the trans continuum mean for trans politics? If trans means more than a minority, then trans politics do not end at minority rights; rather, as trans activist Leslie Feinberg has emphasized, trans politics call for universal liberation. When we achieve that goal, it will be a cause (that is, a reason) for celebration. Until then, it is a cause (that is, an activist initiative) worthy of everyone’s participation.

REFERENCES

Enke, A. (2012). Enke. A. F. (2012). The education of little cis: Cisgender and the discipline of opposing bodies. In Enke, A. (Ed.), Transfeminist perspectives in and beyond transgender and gender studies (pp. 60–77). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Solomon, D. (2013, January 18). Guy talk: Why a straight man like me cares about transgender rights. The Frisky. Retrieved March 2014, from http://www.thefrisky.com/2013-01-18/guy-talk-why-a-straight-man-like-me-cares-about-transgender-rights/

Some people prefer to use the term queer to describe the many groups that make up the LGBTQ spectrum. Queer is a term that has been reclaimed by many LGBT people, and it is often used as an umbrella term for anyone who is not cisgender and heterosexual. Others of us use it as a political term that implies being radical and transgressive, separating ourselves from other LGBT groups that seek more traditional forms of acceptance. However, there are many of us who also find it difficult to use this term because it can carry negative connotations. Like any controversial term, it is best to allow each person to identify themselves with the term rather than using it to talk about someone else.

“I am a queer, pansexual, polyamorous, kinky, femme genderqueer faggot. ‘Queer’ is ambiguous and fluid. Like ‘genderqueer, ’ it critiques the binary system and creates a space for me to live outside the binary confines. But the term ‘queer’ is also important to me because of its politics. Obviously not all queers think alike but, to me, ‘queer’ is about questioning and/or rejecting normative views. Some of my own beliefs include dismantling capitalism and working on wealth re-distribution; ending the prison system; and eliminating the gender binary. Bisexual assumes there are only two genders, which is inaccurate. I am attracted to queers and fags of all genders, so ‘pansexual’ is how I identify. I’m femme, though for the meantime I restrain myself from dressing or appearing how I would like to because most people perceive me to be female and I want to be perceived as a femme genderfucker, not female.”

“I would find it offensive if someone called me a fag or queer, but only because those are hateful words.”

For some of us, our sexuality is very important to our self-identity and it interacts with our gender identity. Some trans women who identify as queer or lesbian refer to ourselves as trans dykes. Like many cisgender lesbians, we have reclaimed the derogatory term dyke and use it in positive ways. Some of us who are transmasculine identify as trans fags, and reclaim the word fag in the same way.

“Some of the terms I use to identify myself are trans, trans man, trans guy, guy, boy, queer, boy with a vag, genderqueer, gender bender, aspiring femme, trans fag, and transgender. I like the term trans because it acts as an umbrella term for all kinds of gender variant people, so even though I would be called a transsexual by the medical establishment, trans unites lots of different people under one flag, and we need unity in our community if we’re going to get anything done. I like queer for the same reason, because it unites lots of non-normative sexualities under one term, and also because I like how it sounds and its secondary definition of ‘strange.’ The terms I use for myself have changed as I’ve become more confident with my transition and my identity in general.”

“I currently describe myself as a girl, lesbian, a trans woman, or a trans dyke. Girl is the term I most heavily identify with, and it simply feels right which is more than I can say for most terms. I occasionally use the terms trans woman or trans dyke which I mildly identify with but do not give the same comforting sense of simple correctness that I feel when I use the term girl.”

Within North America, people of color (POC) have created numerous terms to better define ourselves and explain how we feel about our gender and sexuality. Same-gender loving (SGL) is often used to replace terms like gay or lesbian. Masculine of center (MOC), a term coined by B. Cole, provides an opportunity for people of any sex and across the gender spectrum to identify as masculine without denying our feminine qualities. Similarly, the terms transmasculine, often used by trans men, and transfeminine, often used by trans women, can convey that we fall generally to one side of a gender binary, but that we are not limited by the binary. The term boi is sometimes used by young trans men or by cisgender lesbians who see themselves as somewhat masculine.

Online Toronto-based Stud Magazine offers crisp images of masculine-of-center people along with spotlights on health, education, and employment.

Some of us use specific terms like translatin@ that combine our culture and gender identity. Numerous other terms have come out of communities of people of color. For example, some of us who were assigned female at birth and have masculine identities do not necessarily identify as trans. We may use words such as aggressives or AGs, playas, studs, G3 (gender gifted guy) and boys like us to describe our identity and gender presentation.

The Aggressives (2005) is a movie directed by Daniel Peddle about six young people of color in New York City who were assigned female and identify in different ways as masculine.

“Queer, Pansexual, Transfeminine womyn of color. I am politically Queer. I don’t like the term ‘bisexual’ because it assumes there’s only 2 genders when there are so many more. I like ‘transfeminine’ because it relates to my journey of being born male and living in a body producing testosterone while transitioning into a feminine identity. Womyn of color, because I am.”

“I am a transgender Latina woman. I chose to identify as a transLatina because I crossed the gender binary and I am of Mexican descendence.”

The term tranny is very controversial. Coming from the outside world, it is often experienced as rude, demeaning, and harassing. However, some of us use this term to talk about ourselves, especially when we are in circles of friends, and feel that we are reclaiming it for ourselves.

“I have a love/hate relationship with the word ‘tranny’. . . it can be really misleading, and it has the potential to be really derogatory, and that’s certainly not my intention. I use it precisely because it’s a rubbish word. It’s completely useless. I use it to show how useless it is.”

“I like other trans people who are my friends calling me a tranny. But I don’t like it when anyone else does.”

“I’m not keen on ‘tranny’ at all, but it’s in general use (typically by people who think it’s completely harmless, and/or by people in the drag community). . . the problem with it is that it is THE go-to joke for drunken frat-boy humor (e.g. ‘that chick Steve was macking on last night was a huge tranny, ’ etc), and by using it ourselves we only legitimize it for more cruel and hateful uses.”

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves New York City Forum (photo by Katia Ruiz).

Even within the trans community, who can reclaim the word can also be a controversial issue. The term has more often been used in a context of violence and hate toward transfeminine people. Some trans men feel that we should not use the term, because it has not been used against us in the same ways.

“I feel like the term ‘tranny’ is too scary a word for folks with MTF trans experiences, and [as a transmasculine person] it’s not mine to reclaim.”

Depending on where we live, other terms may be used to describe our experience and identity in negative ways.

“Terms I find offensive would be the usual derogatory terms. Particularly in my country (South East Asian context), it would be transvestite. The media and government generally use this term for transsexuals with GID and make us look like freaks in dresses. So I am pretty offended by this term. Oh and there’s Mak Nyah (Malay language), it means transvestite too and it is a very crude term.”

“‘She-male, ’ ‘he-she, ’ that kind of thing is hate speech.”

Some of us do not feel we fit in the gender binary. Under the gender binary, there are only two genders and everyone has to be either male or female. We may understand our identities as falling along a gender spectrum.

Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation, edited by Kate Bornstein and S. Bear Bergman, features essays and comic strips from radical trans and genderqueer voices.

Trans Bodies, Trans Selves Seattle Forum (photo by Ish Ishmael).

“I despise labels and know who I am. I do not feel I need to label myself and narrow myself and narrow myself in order to make a binary society more comfortable in their dealings with me.”

“First I came out as bi. Then a lesbian. Then a dyke. Now as gender fucked up. The first were so much easier: I was saying something about myself. This is harder: I’m telling people what I’m not. It’s a lot easier to say, ‘I think women are sexy’ than it is to say, ‘I don’t know what a woman is anymore, but I know it isn’t me, and no I’m not a man, and I really can’t explain it.’”

We may identify as gender variant, genderqueer, pangender, or gender fluid, terms used by those of us who feel we are both male and female, neither male nor female, in between genders, on a continuum, or outside the binary gender system altogether. We may consider ourselves androgynous, having both male and female characteristics, or being somewhere in between. We may not feel we have a gender or that we want to choose a gender, and may define ourselves as nongendered or genderneutral. Those of us who consider ourselves genderless and also desire gender-neutral bodies may identify as neutrois.

“I consider myself genderqueer because I feel uncomfortable with the gender binary, and I am unhappy when I feel pressured to conform to the binary gender role expectations of women or men. I think a lot of cisgender people feel the same way to a degree.”

“I specifically consider myself MTF TS, but right at this moment I would describe myself as genderqueer—not as a goal or a political statement but a recognition of just how between/both I am right now.”

“Transgender, transsexual, transman, queer, FTM, femmy boi, androgynous, pangendered, tranny, transfabulous. I use ‘pangendered’ rather than ‘bigendered’ because ‘bi’ implies that I think that there are only two genders, when my mere existence proves that there aren’t. ‘Pangendered’ fits pretty much everything. . . ‘Transfabulous’ is my own word. I think it’s fantastic.”

Some of us understand ourselves as Two-Spirit, a category that exists in some Native American cultures. For many groups, being Two-Spirit carries with it both great respect and additional commitments and responsibilities to one’s community, including acting as healers or providing spiritual guidance. The term can apply to people with nonheterosexual identities, in addition to people who are gender nonconforming. It is important to note that Two-Spirit is a term that comes out of specific cultures, and it may not be appropriate to use as a self-definition if we are not part of these cultures.

“I like FtM, trans*, transman, two-spirit (yes, I am First Nations), queer. . . all based on context or situation.”

“Two-Spirit is the best word to describe myself. I hate the words transgender, queer, gay, fag(got), trans man, boi, gender-bender, gender variant and gender queer. Those words belong in white culture and I don’t like their oppression and colonization to extend to my identity because they don’t own that.”

“I’ve started identifying with the term two-spirit, but I’m not sure about it yet. I am part Native American but I look much more like my European ancestors, so I fear that if I used the word it would be seen as co-optation.”

The Genderqueer Identities Web site (genderqueerid.com) provides resources and answers to all kinds of questions about genderqueer identity.

Outside of North America, there are many communities across the globe that incorporate third gender or third sex categories, allowing for gender nonconforming people to create new spaces to express their gender identities. Examples include the Fa’afafine in Samoa, Kathoey or Ladyboys in Thailand, and Hijras in India and Pakistan. Some people in the United States, especially in communities of color, are using the term third gender to self-identify.

Hijras dancing (copyright Glenn Losack, MD/Glosack Flickr).

Jamie Roberts and Anneliese Singh

Shabnam Baso was the first transgender woman to be elected to the State Legislative Assembly of Madhya Pradesh, India, in 1998. Baso’s nickname was Mausi (or auntie)—which is a common term of endearment and familiarity in South Asian culture. Baso famously took up the mantle for Hijra rights, encouraging the Hijra community to take a more active role in everyday Indian society. The result of British colonization for the Hijras in India has been a specific loss of status and significant public health struggles. The British government created a statute, which they inserted into the Indian Penal Code in 1872 (Section 377), criminalizing sexual activity that was “against the order of nature.” This penal code affected much of the way the Hijras were viewed in society. While the Hijras once held sacred status and prescribed roles in religious rites pertaining to births and marriages, in modern times the community struggles with issues of HIV/AIDS and homelessness.

Although the Hijras experienced significant destruction of their sacred rites, they continue to engage in activism. India granted suffrage rights to Hijras in 1994. In 2008, Bangalore police arrested several Hijras on charges of public begging. Unfairly targeted, these same Hijras were mistreated in jail, and a group of up to 150 activists from community-based organizations and women’s groups worked toward their release. Many of these activists were part of Sangama, a human rights organization dedicated to furthering LGBTQ rights in India, in addition to engaging in social services and political advocacy.

Many of us like to play with gender, even if we identify as male or female. Some of us enjoy dressing up and performing. We may live most of our lives as men but perform as drag queens in shows or live as women and perform as drag kings (formally known as female or male impersonators). As drag queens and drag kings, our costumes are often outlandish and over the top. Trans people, not just cis people, can perform in drag shows. Trans men can perform as either drag kings or drag queens and trans women can do the same. Drag is about having fun with gender.

We Happy Trans (wehappytrans.com) is a place for sharing positive perspectives about trans people from around the world.

“I am a drag king who performs a great deal and spend a fair percentage of my life impersonating a man. I am very masculine, but still hold onto my femininity as it is a part of me.”

“I perform as a masculine persona or bind/pack/draw facial hair on for fun and to express myself butch.”

The Drag King Book, by J. Jack Halberstam and Del LaGrace Volcano, is a collection of essays, interviews, and photographs.

Whether or not we cross-dress or perform in drag, we may engage in genderbending or genderf*cking, where we purposefully play with gender, wearing clothes we are not supposed to wear or acting in ways that people do not expect.

“Genderqueer, androgynous, trans, transgender, genderf*ck (every so often), gender-variant. I like the openness of these. They never box me in and have a lot of flexibility.”

Venus Boyz is a 2002 film directed by Gabrielle Baur that explores drag king culture.

But not everyone embraces this idea. For many of us, our gender presentation does not feel like something we are experimenting or playing with.

“I don’t like it when people use words like ‘genderf*ck’ to describe me, as I don’t see what I’m doing as play. It’s who I am.”

Those of us who live most of our lives in our birth-assigned gender but like to wear the clothes typically worn by another gender may refer to ourselves as cross-dressers, or more simply dressers. In English, an older term for cross-dresser is transvestite. Many people today find it offensive, although words similar to transvestite are in common use and not necessarily considered offensive in some other languages. During other periods in history, there were many female cross-dressers. However, today, since women in Western countries are typically given more leeway in their wardrobes than men, most of us who identify as cross-dressers were assigned male at birth.

Drag King Murray Hill, New York City Dyke March, 2007 (copyright Boss Tweed).

“Cross-dresser. I’m just starting out on my journey, so at the moment, I’m just dressing, but I want and fully intend to go much further.”

“I am comfortable with transgender, transsexual, genderqueer, trans woman, femme, MTF, cross-dresser, transvestite, tgirl. I picked them because they are pretty much the only terms I don’t find degrading.”

Sometimes, we cross-dress only in our own homes, or as part of sexual play, and sometimes at public functions. For some of us, it may be an early part of our transition process, and for others, it may be our chosen gender expression.

Pronouns are one type of word that we use to talk about people. We often call someone “he” or “she” instead of using a name. Many of us want people to continue using these words to describe us when we transition, though our preferred (gender) pronouns (PGPs) may change from “he,” “him,” and “his” to “she,” “her,” and “hers,” or vice versa. When we are not sure which pronouns someone prefers, it is polite to ask, “What pronouns do you use?”

“Personally, I find it charming when people use the appropriate name and pronouns, and go so far as to ask when they’re unsure.”

“I feel really relaxed and natural when people switch up their pronouns for me. They can use him, her, hir, zi, shi. . . Anything. . . I do enjoy being called ‘male’ pronouns more often, though. If you aren’t sure what to call me right then, listen to how I refer to myself, and take it from there. If I sense your uncertainty (and I probably will), I’ll help you out. Or you could just ask. I really don’t mind.”

Others of us prefer to have people refer to us using gender-neutral pronouns. One way to do this is to use the word “they,” which is traditionally a plural pronoun, and apply it to just one person rather than multiple people. With some adjustment to the way we are accustomed to speaking, we can become used to phrases like “What are they doing today?” or “What’s their favorite restaurant?” and know that both we and the others we are talking to understand that we are speaking about just one person, who was named earlier in the conversation. Other gender-neutral pronouns did not exist in English until recently and were invented in order to find new ways of talking about people in nongendered ways. These include zhe or ze (pronounced “zee”) as a replacement for s/he, and hir (pronounced “here”) as a replacement for him/her. Gender-neutral titles (replacements for Mr. or Ms.) include Mx. (pronounced “mix” or “mixter”), Misc. (pronounced “misk”), and Mre. (pronounced like the word “mystery”).

In some languages, pronouns are gender-neutral. For example, when speaking Mandarin, there is no distinction between male and female pronouns. In other languages, people are developing gender-neutral pronouns as we are in English. In Swedish, the gender-neutral pronoun hen is starting to be used by some people in place of han (he) or hon (she).

“I prefer that people use gender neutral pronouns but that rarely happens because I do look quite femme (but don’t present as such). Even when I talk about this with people, they still use feminine pronouns.”

“I would prefer it if people referred to me using gender neutral pronouns (I use sie and hir) and possibly gender neutral salutations (Mre.).”

Some languages employ only gender-neutral pronouns. Others, like English, make it difficult to talk about people without using gendered terms.

For the past few years, some teenagers in Baltimore have been using the gender-neutral pronoun “yo” when talking about people. For example, they might say, “look at yo,” or “yo’s wearing a new jacket.”

“I appreciate it when other people recognize my gender expression and take that in consideration when referring to me, as there are gender-neutral alternatives as well. Luckily, in the Finnish language we have a gender-neutral personal pronoun. Referring to me simply as a female based on my biological body makes me feel really uneasy, as it surpasses my sense of self and how I see my gender.”

“Gender neutral/third gender pronouns aren’t available in German. In English, however, I prefer ze/hir, if I’m in a suitable setting (either online or real life). I can’t stand being called ‘it’.”

At times, people mispronoun us, calling us by incorrect pronouns, or misgender us, assuming incorrect genders. Mispronouning and misgendering can be intentional or unintentional. When it is intentional, it can be used as a form of harassment. Using our chosen pronouns, or substituting gender-neutral pronouns when it is unclear which pronouns we use, is a way others can treat us respectfully.

“Unfortunately, in too many situations there are people who can reluctantly recognize that I am a woman, but upon discovering that I’m genderqueer they insist that they cannot help but mispronoun me and think of me as a man.”

“They,” Portraits of a Noun (Hill Wolfe).

As trans people, we often face discrimination. Many people intentionally harass or bully those of us who do not fit into their visions for a gendered society. However, there are also many people who are potential allies to us who do not yet understand our identities or the struggles we face. They may unintentionally use offensive language or misinterpret our gender expressions. Meeting others and connecting through individual interactions is one of the most effective ways of creating allies to our communities. However, we all have our own sense of how much time and effort we want to spend educating others.

Unlearn transphobia (copyright Gustavo Thomas).

As trans people, we experience different types of discrimination based on our identities and presentations. Transphobia is discrimination based on our status as transgender or gender nonconforming people. Transphobia overlaps with homophobia (discrimination against gay, lesbian, and bisexual people), sexism (discrimination based on our perceived sex), and misogyny (hatred or dislike of women). For example, gay men who are seen as especially feminine are more likely to be harassed than those who are seen as more masculine. Young gender nonconforming people, who may be trans but may also be gay, lesbian, bisexual, or sometimes straight and cisgender, are bullied every day in schools across the world. Trans-misogyny, a term coined by trans writer and activist Julia Serano, is a form of misogyny directed at trans women.

“There is no innocence nor insignificance to the mistake of ‘she’ for ‘he’ when referring to a person who has chosen to take on a ‘wrong’ pronoun, even if it is done thoughtlessly; that thoughtlessness comes from and supports the two cardinal rules of gender: that all people must look like the gender (one out of a possible two) they are called by, and that gender is fixed and cannot be changed. Each time this burden shifting occurs, the non-trans person affirms these gender rules, playing by them and letting me know that they will not do the work to see the world outside of these rules.”—Dean Spade, founder of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project

Julia Serano is the author of Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity.

While all people who fall under the “transgender” umbrella potentially face social stigma for transgressing cultural gender norms, those on the male-to-female or trans female/feminine spectrum generally receive the overwhelming majority of society’s fascination and demonization. This disparity in attention suggests that individuals on the trans female/feminine spectrum are targeted, not for failing to conform to gender norms per se, but because of the specific direction of their gender transgression. Thus, the marginalization of trans female/feminine spectrum people is not merely a result of transphobia but is better described as trans-misogyny, which appears in numerous ways in our society. For a few examples:

-Feminine boys are viewed far more negatively, and brought in for psychotherapy far more often, than masculine girls. Psychiatric diagnoses directed against the transgender population often either focus solely on trans female/feminine individuals or are written in such a way that trans female/feminine people are more easily and frequently pathologized than their trans male/masculine counterparts.

-The majority of violence committed against gender-variant individuals targets individuals on the trans female/feminine spectrum. In the media, jokes and demeaning depictions of gender-variant people primarily focus on trans female/feminine spectrum people.

-Perhaps the most visible example of trans-misogyny is the way in which trans women and others on the trans female/feminine spectrum are routinely sexualized. The common (but mistaken) presumption that trans women (but not trans men) are sexually motivated in their transitions comes from a broader cultural assumption that a woman’s power and worth stems primarily from her ability to be sexualized by others.

Discrimination is not always (or even often) the result of an active bias against or hatred of a certain group. Our cultures are made up of established practices and systems that assume certain identities are the “default.” For example, cissexism and cisnormativity describe a systemic bias in favor of cisgender people that may ignore or exclude transgender people, and heterosexism and heteronormativity describe a systemic bias in favor of heterosexual relationships.

“I have met heterosexual transgender people who are actually homophobic. It kind of blows my mind because they had a sex change and have the same chromosomes as their partner. That doesn’t mean they’re gay but I just think that would open their minds a little.”

“Some people, even within the trans community, seem to think that because we’re attracted to guys then we’re not really trans, and that it would be easier for us to ‘stay girls.’ I’ve heard that from people and it’s really disappointing that people are still that close minded.”

Victor Mukasa, an LGBTQ rights activist from Uganda (copyright Linda Dawn Hammond/Indyfoto.com).

Many of us fit into at least one of the “default” categories of our society; this gives us privilege in certain ways. Privilege refers to advantages conferred by society to certain groups, not seized by individuals. It can be difficult sometimes to see our own privilege, especially when we face discrimination because of our transgender status or other parts of our identity. Trans people reflect the diversity of our society and, in addition to our transgender status, we also have multiple identifications based on other factors, including our race, ethnicity, culture, class, age, immigrant status, disabilities, size, and numerous other characteristics.

The multiple identities and spaces we occupy can be interpreted through the idea of intersectionality, a concept coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) and widely used among feminists of color. Intersectionality is the concept that our identities are complicated—our experiences as people of a specific gender, race, sexuality, ability, and ethnicity are interconnected and cannot be separated. Intersectionality allows us to approach trans discrimination as an interlocking system of oppressions rather than as one solely based on gender.

Facing discrimination based on any of these factors, along with transphobia, can be devastating, especially for those who have been cast from families or have little community, financial, or psychological support.

“I think a lot of times the wider community forgets that being trans doesn’t automatically make you white and able bodied. My trans men friends who are not white have a harder time finding a packer that could believably be their skin tone. I, and my other trans friends who have different bodily ability, are sometimes glossed over by other trans people when looking at bathroom access and other needs. From what I have seen, the result is that our smaller groups bond even more tightly and instantly than the trans community more broadly. To a certain extent we are taking on the world over our gender and then, because of intersection of identity, we are taking on some sections of the trans community as well who may be racist or clueless as to how their bodies are actually a benefit to them.”

“I am a fat, low-income trans person with a non-visible disability. While I am not involved in any official subgroups within the trans community I’m currently in, I do tend to gravitate toward people who are aware of their privileges and the intersectionality of multiple aspects of people’s identity.”

“As a formerly homeless and currently low-income trans woman, I sometimes have very little in common with middle class trans guys who are college students. The issues that affect me are different. I’m worried about whether the unemployment office is going to respect my identity.”

Some of us have disabilities, impairments, or are members of the Deaf community. This can influence our ability to participate in community activities, and change our relationship with other members of the trans community.

“I am disabled and trans, so I know other disabled transfolk, just by being involved in both communities. We talk about issues that relate to how they intersect: how do you get health care for important things like hearing aids, wheelchairs, medication, when you present as a gender different from the ones on the form? My neurological disability is affected by hormones, which makes me scared to even bring it up to my doctors. It’s something that’s not discussed in the larger trans community.”

Joelle Ruby Ryan is a lecturer in women’s studies at the University of New Hampshire, the founder of TransGender New Hampshire (TG-NH), as well as a writer, speaker, and long-term social justice activist.

I am a genderqueer, trans woman. I also weigh over 400 pounds. These two realities have shaped my life in ways I never imagined, for both better and worse.

When I was a young, fat, feminine boy, my teacher was concerned that I was both out of shape and not behaving like the other boys when it came to recess and athletics. This is just one instance when my fatness and my transness came to be inextricably linked.

While I came out as trans at age 20, I didn’t start peeking my head out of the “fat closet” until my mid-thirties. As I grew much fatter, I started to notice the discrimination and stigma from my family, my doctors, and the “caring” friends who expressed their worries. I became much more aware of the constant fat-shaming in the media, and the push by the medical establishment to forward the notion of the “obesity epidemic” and the need for dangerous gastric bypass surgeries.

But when I came out as queer and trans back in the early 1990s, I made a promise to myself: never to allow others to make me feel bad about who I am. I was sick and tired of others hating on me in a misguided attempt to puff up their own sagging self-esteem. And I also decided, after reading the fabulous book Fat!so? by Marilyn Wann, that I really didn’t have to apologize for my size, and that fatness is a benign characteristic much like being blond, or left-handed, or tall, or flat-footed. It was not being fat that was the problem, but the prejudiced society in which the fat person lives.

As people who are marginalized due to our bodies and our identities, the trans community should be natural allies to the fat community. Sadly, I have witnessed a lot of fatphobia in the trans community. Some trans folks seem to think that by conforming to other hegemonic bodily standards (thin, nautilized, “passing,” traditionally attractive, etc.) they will become more palatable to the mainstream. But we can never throw enough people overboard to win approval from our enemies.

We have learned the value of affirmative slogans over the years: Black is Beautiful! Gay is Good! Trans is Terrific! And the latest: Fat is Fabulous! In order to be a whole, healthy community, we must celebrate the dazzling diversity of everyone and stop the fat-hate once and for all.

NOLOSE* (nolose.org) is a community of fat queers and our allies with a shared commitment to feminist, antioppression ideology and action.

“I have some medical issues and have been involved in groups for people with disabilities but at those groups I’m normally the only person who is gender diverse except for one project that was for people who have disabilities to discuss issues of sexuality as a performance piece. I know a few people who have disabilities and are somehow queer.”

Similarly, many of us come from working-class and poor communities and our experiences of gender and ability are profoundly affected by our experiences of classism and access to class privilege. Financial status may limit our ability to transition in many ways. We may not be able to afford the cost of name or gender change, to buy clothes that match our gender, or to have procedures such as surgeries or electrolysis that can affect the way we present our gender to the world.

“I’m working class and have a minor physical disability. The class issue comes up in ability to get medical care for trans issues.”

“I’ve contemplated surgery, but the cost is a bit of a detriment to that particular dream.”

“I grew up middle class, was lucky and privileged enough to receive an upper class education, and currently work in a service/lower income job. So my class experience is a mixed bag. Transitioning has been really difficult for me mostly because of the lack of money—there are times when I have been off and on T because of it for months at a time. So I am pretty resentful when I see people who have access to that kind of monetary privilege transition and get surgery in 6 months and then become an authority figure on ‘trans issues, ’ when I don’t think we have the same experience or care about the same things. Intersections with other social justice issues like racism and classism are really integral to a good trans politic, and I think that is missing from the narratives of a lot of the spokespeople in the FTM movement. I would love to see a non-white or gay-identified or low-income (or any combination) trans masculine person be a highly visible person in the movement, but I don’t see that right now and I think it’s disheartening for a lot of younger trans folks.”

Where we live can also affect our experiences as trans people. In rural areas we may have less access to trans-specific resources and may find unique ways of creating places of comfort and safety for ourselves. Sometimes the assumption is that those of us who live in small towns have to deal with more bigotry and transphobia. This can be true, but it is not always the case.

The Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN) did a survey of LGBT youth in rural areas called “Strengths and Silences: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Students in Rural and Small Town Schools.”

“Defining myself has never been an easy task. . . growing up in small town Indiana in a roman catholic family, I was never exposed to the various terms, let alone ‘transgender’ or ‘transsexual.’ I had only seen the word ‘shemale’ online (but I didn’t think much of it, I’m just a normal girl born with a penis).”

“I am in a small town with strong conservative views. The fact that we have a handful of transpeople surprises me.”

“Since I am generally seen as female, I tend to say I am. This is particularly the case since I live in a remote rural area. It parallels the fact that my partner, who is genetically female, and I are both fairly butch. We don’t say to people that we are dykes, but we don’t say we aren’t. We aren’t closeted, we just don’t push the point.”

“For a variety of reasons I chose to not move as I transitioned, which means by virtue of shifting appearance, name, and pronouns, my personal life was public. . . Staying in my home town was more important for mainly familial reasons.”

The ways in which we each experience discrimination may change as we transition. Trans women may contend with sexism and misogyny in the workplace for the first time. Trans men, who often look younger than cisgender men their age, may face ageism and be seen as less knowledgeable or capable than others. Trans men of color often find themselves in the position of being suspected criminals much more often than when others viewed them as masculine women.

“Being perceived as a Black man is different than being perceived as a Black woman in a lot of ways, not to mention if you’re neither perceivably man OR woman. I think that it’s important for us to have those conversations since conversations about race, ethnicity, and their social connotations are rarely had in the LGBTQ community.”

“I was recently told that no matter how masculine I ‘tried to be, ’ I was always a cute little Asian girl with a cute little face and body. In fact, this person told me she considered me to be ‘femme.’ This was a strong reminder that my gender presentation is inextricably linked to my race. There are notions about Asian masculinity at play here—that Asian men are not as manly as men of other races. There are also notions of Asian femininity—that Asian women are weak, that Asian women are hyper-feminine and hyper-sexualized. There is no room here for folks who were Female Assigned at Birth to be androgynous or masculine or strong.”

“I am discovering what it is to be Chican@ and trans on the day to day, how those identities intersect and relate to each other. As someone who can never fully identify as American or Mexican, but as hybrid of the two, I’ve learned to take the lessons from that liminality and use them in regards to my gender identity. Sometimes it’s okay to occupy and exist in those gray, in between areas.”

Fredrikka Maxwell is happily retired and spends time with her partner Connie Goforth. She sits on the board of the Tennessee Vols, co-chairs the Dignity USA trans caucus, and gives seminars at varied trans- and church-related conferences.

I am a black transsexual. Like the Tooth Fairy or Santa Claus, a lot of people simply don’t believe we exist. There was a time when I didn’t believe we existed, either—but by the middle of my high school career, I had a very strong suspicion.

As an adult, at the Foundation for Gender Education convention in Philadelphia, I noticed that I was the only black person in attendance save for the hotel employees. That’s another dirty little secret of the trans community: It’s not as integrated as it likes to bill itself. I knew then that I was going to share a black perspective at the conference, because unless I did, it wasn’t going to get done.

I started where I was familiar: my own story.

I was born in Savannah, Georgia. My dad jumped out of airplanes and helicopters for a living, which meant that my three brothers, my sister, and I went wherever the Army assigned Dad. I have a wonderful sister who has been a frequent companion at events like the Philly Trans Health Conference and Call to Action, a liberal Catholic group where I live. She was the first family member I came out to and she professed unconditional love from the start. My brother has accepted me with much love at his house near Atlanta—I have warm fuzzy memories of hot chicken wings and ice-cold Rolling Rock beer at his house before the Southern Comfort conference.

But it wasn’t always that way. My brother once said that he didn’t want his wife and kid exposed to me; I later told him we were talking about my life, not anthrax. It took my mom 10 years to reach the point where she concluded that I was hers, no matter what. My church family was divided about my transition, and some were clearly unhappy about it. I lost friends at work and outside. It wasn’t easy.

I earned my BA from the University of Tennessee at Martin, but I couldn’t get hired by any journalistic outlets. Maybe I wasn’t white enough, maybe I wasn’t bright enough, maybe I wasn’t something enough. I eventually found a job in an unlikely place—the Metro Police Department in Nashville, a job I held for 25 years before coming out in 2001 to live as the woman I knew myself to be.

In Atlanta, at Southern Comfort, I ran my first seminar, appropriately named Sharing the Black Perspective. Southern Comfort and Call to Action, which do not have much black presence, know me now. I am not a rookie anymore, and I feel inspired to do more seminars as time goes by. The mission ahead, to share the black trans perspective, is one I’ve embraced wholeheartedly.

We each have unique ways of understanding and relating to our genders. The ways we talk about and explain these identities are important, and they are always changing. Ultimately, we recognize that many people have intersecting identities and many of us have claimed or reclaimed new terms or labels that have meaning for us specifically. Respect for the self-identity and changing nature of our identities is the glue that binds our communities together. The best way to make change is to assume less and ask more. We do not always agree on terminology and definitions. We define and redefine ourselves, and continually debate within our communities. This conflict can birth understanding, which in turn can encourage healthy dialogue. During all of this, we continue to strive for wholeness while being our many selves.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Brown, M. L., & Rounsley, C. A. (2003). True selves: Understanding transsexualism—for families, friends, coworkers, and helping professionals. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Crenshaw, K. W. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

Currah, P., Moore, L-J., & Stryker, S. (Eds.). (2008). Trans-. Women’s Studies Quarterly, Fall/Winter, 36(3–4).

Herman, J. (2009). Transgender explained for those who are not. Authorhouse.

Hines, S., & Sanger, T. (Eds.). (2010). Transgender identities: Towards a social analysis of gender diversity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nanda, S. (1999). Gender diversity: Crosscultural variations. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Nestle, J., Howell, C., & Wilchins, R. (Eds.). (2002). GenderQueer: Voices from beyond the sexual binary. Los Angeles, CA: Alyson.

Serano, J. (2007). Whipping girl: A transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press.

Stryker, S., & Aizura, A. Z. (Eds.). (2013). The transgender studies reader 2. New York, NY: Routledge.

Stryker, S., & Whittle, S. (Eds.). (2006). The transgender studies reader. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sycamore, M. B. (Ed.). (2006). Nobody passes: Rejecting the rules of gender and conformity. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press.

Teich, N. M. (2012). Transgender 101: A simple guide to a complex issue. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Valentine, D. (2007). Imagining transgender: An ethnography of a category. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

* Quotes in this book, unless otherwise specified, are taken from an online survey of transgender and gender nonconforming people on the Trans Bodies, Trans Selves website.