Heath Mackenzie Reynolds and Zil Garner Goldstein

FIGURING OUT WHO WE ARE AND WHO WE WANT TO BECOME IS A UNIVERSAL HUMAN EXPERIENCE. For many people, this process becomes less active over time, as we settle into our sense of self and build a community and a life around that identity. But not for everyone—many people find the process of defining who they are to be lifelong and full of changing directions, shifting goals, new communities, and new identities. As trans people, we may find that we are plunged back into a more active phase of self-discovery than we had been before coming out. Once we make a decision to begin making changes that will better reflect our identity, there are numerous ways to start. Some of us spend a considerable amount of time thinking about how we would like to be addressed and whether we want to change our name or pronouns.

CHOOSING A NAME

The process of picking a new name can be one place to start thinking about how we want to integrate the different parts of our lives. The most important part of coming up with a name is feeling like it fits. There are many different strategies for coming up with a name.

“Changing my name was a very important aspect of re-creating myself in the form that I want to be—of becoming myself, as my own ongoing creation process.”

Many people find a name that feels good by looking into their own family or cultural background, or examining the parts of their identity and history that have played the biggest role in shaping their sense of self. Talking with trusted friends and family can help. It can also be useful to try out the new name with a few people before telling lots of people about the change.

There is, however, such a thing as too much advice. It is important to feel confident in the name we are choosing but also to avoid thinking about it for too long. You do not want to repeat your new name so many times that it loses meaning before you have even settled on a decision.

When we ask other people about possible names, we have to be prepared for all kinds of answers. We may not hear what we want, and we certainly might not hear what we are expecting to hear. It can be hard to ask a friend or family member about a name, or some other aspect of our transition, and hear an answer that is not supportive. Figuring out who to ask can be a challenge, and we can often be surprised by the people around us when we bring up aspects of ourselves related to trans identities.

Sometimes it can be tempting to use names that come from cultures other than our own. When thinking about these names, consider that some of us who come from those cultures may be offended by an outsider’s use of our community’s names. Even if you think a name has a nice sound to it, try to think about whether it is an appropriate choice, given your own background.

Some of us take more time than others to settle on a name. We may even use one name for a year or two and then decide that it does not quite fit. This can be a natural part of our process.

PRONOUNS

Pronouns are the part of speech we use to refer to someone without using their name. Most commonly, people use “he” and “him” or “she” and “her.” Gender-neutral pronouns such as “ze” (pronounced “zee”) and “hir” (pronounced “here”) reflect a gender identity that is neither male nor female. “They” and “them” can also be used to speak about an individual without referencing their gender.

Deciding when to start using new pronouns is often harder than deciding when to start using a new name. Much of the same process we use to choose our names applies to choosing our pronouns. Our use of pronouns may shift over time as our gender presentation changes or as our gender identity shifts.

“When people use my preferred pronoun, I feel like a worthwhile and real human being.”

Some of us begin by using new pronouns with close friends or family, and gradually expand to different friend groups or social communities. Many of us end up using different pronouns in different parts of our life, at least for a while. It may be hard to use gender-neutral pronouns at work, for example, where most people may be unaware of their existence. Some of us have not yet come out at work and use our old pronouns with colleagues.

Over time, we may figure out how to manage having multiple pronouns and even like it, or we may switch to using a more consistent set of pronouns in all contexts. For some of us, pronouns are not important at all, or we might grow tired from using different pronouns in different spaces, so we use whatever seems to be most “default” for those we interact with. Everyone has different strategies for dealing with gender, pronouns, and the world around us.

People Make Mistakes

When we are changing our name and pronouns, it is very common for people in our lives to use the wrong pronouns when referring to us (“misprounoun” us). When someone messes up a pronoun, it often makes us upset, angry, or sad. It can upset the person who made the mistake as well, especially if they care about us. If we decide to correct the person who made the mistake, it is often helpful to say something like “he not she” or “ze not he,” instead of simply stating the correct pronoun. Keep in mind that using gender-neutral pronouns can be harder for people to adopt, and they will likely need more time to adjust.

“At first I delighted in getting folks to use a mix of pronouns—to switch it up. Now I use she/her almost exclusively. It is comfortable for me. When I made that switch, I was very self-conscious when anyone messed it up. I got embarrassed and annoyed. To this day I still flinch when I hear someone mess it up, but I am much more graceful about correcting them if needed.”

TRANS ETIQUETTE

Peter Cava

Following are some of the most important principles for respectfully communicating to, and about, trans people. I have learned these principles from writings by Jacob Hale, Matt Kailey, and Riki Wilchins; videos by Calpernia Addams and Ethan Suniewick; and my participation in trans communities.

• Remember that you’re not the expert on others’ experiences. Everyone experiences gender differently. Exercise humility. Practice good listening skills.

• Honor others’ self-definitions. For example, use others’ chosen names and pronouns. If you don’t know someone’s pronouns, avoid pronouns or ask. If you make a mistake, don’t turn it into a scene, and don’t be too hard on yourself; discreetly apologize or just move on. If you’re in a situation where it would be appropriate to speak about someone’s genitals, use their chosen language.

• Don’t expect others to serve as spokespeople or educators. No one can speak for every member of their group or community. Many trans people are happy to share their experiences. However, no one can be “on” as an educator 24/7. Take advantage of published resources. If you want to talk with a trans person about their experiences, wait until the topic comes up, or ask consent.

• Don’t “out” others as trans. Even if someone is out to you, they may not be out in all areas of their life, such as family, work, and social media. Outing someone can have negative, even devastating, consequences.

• Don’t assume that others’ gender expressions tell you something about their bodies, identities, or sexualities. For example, if someone looks to you like a woman, don’t assume that the person was assigned female at birth, self-identifies as a woman, or is sexually oriented toward men. If you proposition someone for sex and they do not have the genital shape that you were expecting, they were not necessarily deceiving you; rather, you were making an assumption. If you want to have sex with someone who has a particular genital shape, say so. If imagining these scenarios makes you feel uncomfortable, that’s okay. Consider exploring those feelings as a way of learning more about yourself, and consider waiting to have sex until you feel more comfortable.

• Don’t ask invasive questions about others’ bodies, identities, or sexualities. Often the first question that trans people are asked is, “Have you had the surgery?” Other common questions are, “Are you a man or a woman?” and “Do you want to be with a man or a woman?” (As if “a man or a woman” were the only options.) A rule of thumb is that in a situation where it would be considered rude to ask a cis person a particular question, it is rude to ask a trans person.

• Don’t criticize others’ bodies, expressions, or sexualities for not aligning with their identities in a socially expected way. For example, if a trans man does not go on testosterone, don’t make him feel like he is “not trans enough.” Conversely, don’t critique others’ bodies, expressions, or sexualities for aligning with their identities in a socially expected way. For example, if a trans man has sex with women only, don’t make him feel like he is “not queer enough.” We are all enough. At its best, trans-ing gender is not about transitioning from a confining cis box to an equally confining trans box. Rather, it’s about transcending all of the boxes that keep us from being fully ourselves.

Most people do not know what to do when they are corrected on someone’s pronouns. It is not something that is commonly talked about. Letting someone know that it hurts our feelings when they say the wrong thing can help them learn that it is important to us that they not do it again. Try to communicate these issues in a calm and reasonable way, even if you are very upset. Reacting in highly emotional, angry ways can often exacerbate the situation. It can be difficult to strike the right balance, and it definitely takes some practice.

Even if we believe that someone is using the incorrect pronouns on purpose or hurtfully, it is more productive to communicate our needs in a clear, firm way than to appear angry. Set limits, and let the other person know what the consequences of mispronouning you are, including how it makes you feel and how you will respond if they continue to act that way.

CHANGING OUR APPEARANCE

There are many different ways we can make our bodies feel like a better fit with our gender identities. Each of us has different goals as we begin to make changes to our appearance. Some of us make changes to be seen by others as the gender with which we identify. Some of us make changes that result in us looking more androgynous in appearance, which makes it harder for others to label us with a gender.

Some of us choose highly masculine or feminine styles that make our gender clear, while others are drawn toward more casual looks that do not highlight gender differences. Our preference may shift over time.

“When I was younger, I cared about that—and I am a makeup artist so I can do good face, but nowadays I do not wear makeup or even worry about how I look or if I pass. I do glam up for public speaking and presentations, but other than that it is a ponytail and bare face.”

As we begin to change our appearance, we also have the opportunity to express other things about ourselves or to embrace new parts of our personality and choose colors and styles that we may have felt were off limits. Over time, we may shift our ideas about how we want to dress to reflect our personality, more than our gender presentation.

Clothing, hairstyles, and accessories are easy places to start changing the way our gender is perceived by others. Some of us find that these changes give us a sense of feeling at home in our bodies, while for others they are ways of experimenting with how we want to look before making more permanent changes. We can always start dressing a different way, or do something for a little while and then stop. As we begin exploring our gender identity and becoming more comfortable, temporary changes in our appearance can help us decide how we will feel most at home in our bodies and the world.

“When I move, I plan to live like a woman in professional settings and dress and act like a man in casual settings. Even now, as I start to admit to myself that I’m trans, I realize how much acting I do on a daily basis. I change my voice and my mannerisms to present as a female. Before, I thought that this was just how life was, but now I realize that I am acting and I’m acting all the time and that is exhausting. I wish I could change my name, records, get top surgery, and dress like a guy all at once because I would love to stop acting most of the time, but I understand that transition must be a long process. I think living in the gray zone will be confusing and frustrating, but if it helps me sort out what I really want for my body and my gender presentation, then I hope I can get through it without getting called out for it.”

GENDER AND THE VOICE

Lal Zimman, PhD, is a visiting assistant professor of linguistics at Reed College, where he teaches a variety of courses on language and society and conducts research on the relationships between language, gender, and sexuality in transgender and LGBQ communities.

The voice is an important cue in the process of categorizing people by gender, and many trans people shift their speech during transition. These changes may be brought about through individual experimentation, speech therapy, the unconscious process of language socialization, or theatrical or musical training, but many trans men and their providers put greater emphasis on the changes in vocal pitch testosterone therapy may bring about. However, biology cannot explain all of the gender differences found in the voice, and there is tremendous linguistic diversity among people of the same sex or gender.

Anatomy puts some limits on our voices, and exposure to testosterone is known to enlarge the larynx (or voicebox), which generally lowers vocal pitch. But even pitch, which is strongly linked to biology, is also influenced by social factors. Speakers of some languages show much more dramatic differences between women’s and men’s pitch than speakers of others. Most children learn to sound male or female before sex differences in the vocal anatomy develop at puberty.

In addition to pitch, the shape of the vocal tract determines which frequencies will resonate most strongly, and women’s vocal tracts tend to be shorter than men’s. Smiling causes the vocal tract to shorten, while rounding the lips makes it slightly longer. There is also the option of raising or lowering the larynx within the throat, which is something children begin to do early in life.

There are also significant gender differences in the pronunciation of particular sounds. Among American English speakers, women tend to pronounce [s] at a higher frequency than men by placing their tongue closer to the upper teeth while making this sound. The other ways that women’s and men’s voices have been shown to differ tend to relate to the notion of clarity, with women generally speaking with greater precision than men—“mumbling is macho,” as one linguist puts it.

Some trans people may wish to change their speaking styles as part of a shift in gender expression, and the fact that many gender differences are learned rather than innate suggests that kind of change is possible, if challenging. Others may prefer a nonnormative voice, in order to signal a queer or distinctly trans identity.

FINDING OUR VOICES, LITERALLY

Christie Block, MA, MS, CCC-SLP, is a clinical speech-language pathologist who specializes in voice communication training and rehabilitation for transgender people at her private practice, New York Speech & Voice Lab, in New York City.

How exactly is gender conveyed when we talk? Pitch is usually what we first think of. However, many other aspects of speech come into play, including intonation, resonance, articulation, vocal quality, stress, loudness, and speech rate. A combination of some or all of these elements can result in a more feminine voice that sounds higher, smaller, lighter, and/or more expressive, compared to a more masculine voice that sounds lower, bigger, heavier, and/or more matter of fact.

In addition to how we sound, other aspects of communication can display gender. These include word choice, the number of words used, conversation topics, and conversation style (such as the degree of politeness or directness). Gender can also be expressed in nonverbal communication or body language, such as eye contact, facial expression, hand gestures, or head movements.

Some of these aspects of communication are based on biological sex differences of the vocal mechanism, for example, the length of the vocal folds. Many other aspects are based on sociolinguistic norms that we have learned since childhood and that depend on language, dialect, region, socioeconomic class, and other factors.

To explore and learn authentic and effective communication skills, a person can seek help from a qualified specialist in transgender voice and communication, typically a speech-language pathologist. Feedback is an essential benefit of working with a specialist, as new skills are practiced, employed in real life, and established over time. Voice and communication change requires patience, like learning a new language or adjusting to other aspects of transition.

For transgender people who choose HRT or voice surgery, pitch change can occur is certain cases. Transmasculine people who take testosterone almost always experience a welcome effect of lower pitch within the first year of treatment, with an eventual permanent drop of up to an octave or more. Hoarseness sometimes occurs in the initial months of therapy or with each dose. In contrast, feminizing HRT has no known effect on the adult voice. Pitch-raising voice surgery has resulted in widely varying degrees of satisfaction and long-term improvement; pitch-lowering surgery is rare and results are not generally observed at this time with or without these treatments. Voice and communication training remains a recommended form of intervention for feminization or masculinization to address not only nonpitch aspects of speaking but also vocal health issues.

Our communication skills are a fundamental part of us, and we can intentionally change them if we desire. Here are a few tips to get started: (1) Think seriously about the way you talk, focusing on aspects you like and ones you would like to change; (2) mimic people who speak in a way that you like; (3) when talking, use your intuition and try your best—intuition can go a long way; and (4) practice healthy voice habits, such as avoiding excessively high or low pitch. Consult a doctor or speech-language pathologist if you experience hoarseness, vocal strain, or throat discomfort.

Clothing

The simplest way to change how our gender is perceived is through what we wear. Finding our new style can take some time. When searching for ways to dress, the best thing to do is look around. Do you see an outfit you like? Is the person wearing it a coworker, someone you see on the street, or a model in a fashion magazine? We can find good looks anywhere or piece them together from multiple things we see. Finding the different pieces can be tricky, though.

Many of us have specific ideas in mind about the kinds of clothing we would like to wear, and we may have gradually collected a small wardrobe—an item here, an item there. We may have tried on these new garments in the comfort and privacy of our homes, at first, or strutted our stuff on the stage as a drag performer.

For some of us, shopping for what we want can be a challenge. We may be nervous about other people’s reactions or simply uncertain about where and how to begin. In most places, clothes shopping is a highly gendered activity, with physical separation between men’s and women’s departments, different sizing conventions, and style choices and details that we may not fully understand. There are many ways to educate ourselves before we head into a retail store. Arming ourselves with information can help give us the confidence we need to approach staff, try on apparel, and make successful purchases.

Shopping for items online can be a way to build a new wardrobe from the privacy of our own home. Most online stores offer sizing charts with advice on how to take our own measurements and choose the right size. Many retailers also offer online-only sales, special offers for free shipping and returns, and may carry a broader range of sizes than their brick-and-mortar shops. For example, many retail stores do not carry extra-small sizes in men’s clothing or larger sizes in women’s items—these items are often available online, however, providing us with more flexibility to find the right fit in the styles we like.

Thrift stores and secondhand shops can also be a good place to start when we begin shopping. They typically have a large selection of items, often in a range of sizes, at a low price, and can help us figure out what styles and sizes suit our bodies. The staff at such places are also unlikely to interact with us as we browse the selection, and many people use thrift stores to procure clothing items for a range of unconventional purposes—such as theater, crafts, and costume parties—which can put us more at ease with making our purchases. Thrift shops can also be an important source for clothing and accessories if we cannot afford to shop in retail outlets or boutiques. It may take more work, but there are often great finds waiting to be discovered.

Many of us find shopping in mainstream retail outlets to be daunting, but it does not have to be. As in many public settings, acting with confidence can diffuse awkwardness and prevent questions from others that make us feel defensive. It can be helpful to remember that even cisgender people may feel anxious shopping for new clothing. Some of us prefer to take along a trusted friend who can be a second set of eyes to help us figure out whether something looks good, what could be changed to make it better, and to help quell some of the anxiety we feel in new situations.

Many of us have trouble finding appropriate shoes in the right size. There are often specialty stores and online deals available, and sales people are often happy to special order shoes in different sizes. Many discount shoe stores have shoes organized by size, which can also help us from falling in love with shoes that are not made to fit our feet. Transmasculine people may find that there are lines of children’s shoes that look professional enough for work.

Remember that cisgender people come in all shapes and sizes, too. There are tall cis women and short cis men. Some cis women have large feet and some cis men have small feet. Each store’s brand tends to fit taller or shorter, thinner or heavier people, and we simply have to find our match.

Hair

Choosing a hairstyle is another way many of us change our appearance. We may focus on growing, cutting, or styling our natural hair in different ways, or we may use wigs. We may want to choose androgynous hairstyles that allow us to present our gender differently based on different contexts or choose strongly feminine or masculine styles that help others read our gender correctly.

When making a radical change in our hairstyle, communicating with the person cutting our hair is important. Many hairdressers are accustomed to people bringing in pictures and saying, “This is how I want my hair to look.” Take pictures, look for styles online, or cut out pictures from magazines to find something you like, and do not be afraid to tell the person cutting your hair exactly what it is that you want. Let them know how much time you want to spend styling your hair and consider whether you will be able to maintain a look that requires lots of styling product, blow drying, or frequent return visits to the stylist.

If going for a shorter cut, some stylists may be concerned about cutting too much. Worried we will be unhappy with the results, they may leave more length than we want or provide a more feminine shape than many trans men would like. Do not be afraid to ask for the stylist to continue cutting, go shorter, or give the cut a more masculine shape.

If you are growing your hair out, getting intermediate cuts to give your new locks a better style can help make you feel more confident and attractive, and can help the hair stay healthy as it grows. Frequent trims can help avoid split ends that can give hair a ragged look. Sometimes we have to cut some parts shorter while we wait for other parts to grow longer.

SCALP HAIR REPLACEMENT

Hair loss is a source of great stress for both trans women and trans men. In trans women, once we begin taking hormones our hair loss should stop and, to some extent, reverse. The degree to which our hair loss may reverse depends mostly on how much loss we had to begin with. Testosterone-blocking medicine is the most important component in our regimen to combat hair loss and assist in hair regrowth. It is unclear whether using a medication like finasteride or dutasteride when we are already on a testosterone blocker like spironolactone will have any added benefit. Some of us have used minoxidil (Rogaine) with mixed results. Remember that many cisgender women have thinning or receding hairlines as well.

Managing hair loss can involve using wigs, hairpieces, head wraps, bands, or hats, or it can involve any one of a number of procedures. Hair systems usually involve a wig made of real human hair, which is bonded to the scalp using a special adhesive. These systems need to be periodically adjusted and refastened. Surgeries can include scalp advance, where the scalp is incised and stretched forward with an island of skin being removed, or it can involve transplants of individual hairs or blocks of hair. Hair transplants generally involve taking a strip-like graft from the back of the head, stretching the two open ends together and sewing them in place, and then using the graft hair for a strand-by-strand replacement. As with facial hair removal, scalp hair procedures require that they be done correctly. Be wary of discounted procedures or cutting corners to avoid unfavorable results.

Trans men may notice the onset of male pattern baldness when starting testosterone. For some of us, this can be quite dramatic, and we may lose most of our hair very quickly. For others, it may happen after a number of years on testosterone. In general, the older we are when we start taking testosterone, the more likely we are to see balding more quickly, because we are closer to the normal age that other men start to go bald. Trans men have similar options to cis men for dealing with undesired scalp hair loss. Medications like finasteride or dutasteride can help to block the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the hair follicles, and therefore decrease hair loss. Minoxidil (Rogaine) is also helpful for some of us. Acceptance can be key to dealing with hair loss. Many cisgender men experience scalp hair loss and find ways to cut their hair (or shave their heads) that make them feel attractive.

Makeup

Many trans women begin using makeup with transition. We may do this to enhance our feminine appearance or to play around with colors and shades. For some of us, this is a very new experience and can be daunting at first if we have not seen others apply makeup up close. This is the case for many cisgender women as well if they did not grow up in households where makeup was used and would like to start using it.

Trans community members often share makeup tips and even create video tutorials online. Mistakes we often make when first starting to use makeup include putting on too much or choosing bright colors, rather than those that match our skin, eyelashes, and lips.

Nonmedical Body Modification

There are many ways that we can change the presentation of our bodies to make them look more or less masculine or feminine without medical or surgical interventions. We can modify the appearance of our chest and genitals by using a range of wearable accessories.

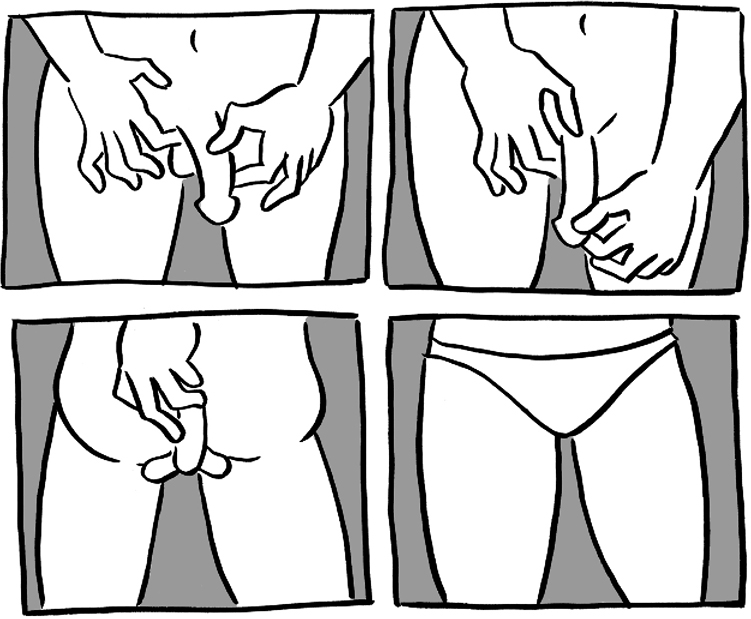

PACKING

Packing refers to putting things in the crotch of our pants to create the outward appearance of a penis and testicles. This look can be achieved in a variety of ways. A folded pair of socks or a condom filled with hair gel (or a similar substance), can create the profile we are looking for, and there are also products specifically made for this purpose. Packers or packeys are made out of silicone or other materials that simulate the look and feel of a nonerect penis and testicles. Packers can be worn with tight-fitting underwear, a jock strap, or a special harness made for them, which is different from a harness used to hold a dildo in place during sex (“strap on.”)

There are two types of packing: hard packing and soft packing. Soft packing is meant to give the impression of flaccid genitals, and soft packers are typically not suitable for penetration. Hard packers, on the other hand, are erect and capable of penetration. We may choose hard packers for visual eroticism or if we intend to have sex later. There are a growing number of “dual-use” packers that offer both wearability and function.

To wash packers, many people just use soap and water. If a packer is used for sex, it should be cleaned appropriately according to what material it is made from. See Chapter 17 for more information on cleaning sex toys.

STAND-TO-PEE DEVICES

A stand-to-pee (STP) device is a tube with an upturned curved opening that can be placed against or underneath the urethra. Urinating into the opening directs fluid away from the body and out the other end of the STP device in front of us.

Some packers are designed, or can be modified, to allow the wearer to urinate through them while standing, and function as STPs. If you are choosing a packer that you wish to modify, look for an option that has a wide base through which a hole can be cut.

There are also many other, nonwearable STP options that can be used in settings where standing to pee, not visual presentation of a functional penis, is all that is desired. Many camping and outdoor supply stores—as well as vendors at many music festivals—sell STP devices that are easy to clean and carry. Some are disposable. STPs may be used by a variety of people for a number of reasons, such as dirty bathrooms, lack of privacy, or no available bathrooms.

It can take some practice to get the hang of using an STP device. Be sure to spend some time practicing at home before taking your new accessory out into the world, especially if you are planning to use it in a public men’s room. Also consider how to transport and clean your device on the go if it is not part of a wearable packer.

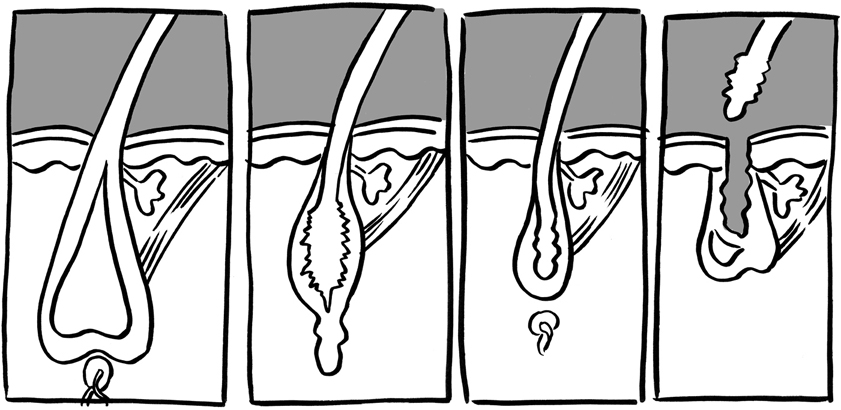

TUCKING

Tucking is a practice that helps create a more feminine-appearing profile. This is most often done by curving the penis between the legs toward the anus, and pushing the testicles up into the inguinal canals, the cavities through which the testicles descend from the abdomen to the outside of the body. To find your inguinal canals, start with one side of your body. Take a finger and push your testicle aside while lifting the finger up toward your body. You should hit an area of skin where your finger can push into your body just slightly. That is the entrance to your inguinal canal on that side.

When tucking, once everything is in its tucked position, some of us use medical tape to keep things in place. Duct tape can cause skin reactions and irritation. Most of us choose to shave the area where tape is used, as this makes the tape stick better and makes it more comfortable to remove the tape. Snug-fitting underwear adds an extra layer of security and creates a smoother profile. Special undergarments, known as gaffs and dance belts, can also be used to keep everything in place when tucking. Gaffs are specifically designed for this purpose, and more easily obtained online, while dance belts—designed to provide comfort and reduce the visibility of external genitalia for cisgender men—are available from many theater and dance shops.

NONSURGICAL BREAST ENHANCEMENT

By wearing a bra and stuffing the cups, many of us are able to create the appearance of larger breasts. Some of us use easily obtainable household materials such as socks or tissue, or fill water balloons with birdseed, hair gel, or similar materials. Padded bras are available at most stores that sell bras, and they can help provide a smoother shape under clothing. Breast forms, also called cutlets or jellies, are different materials molded into the shape of breasts. These are often used to fill out bras, but some are designed to be attached to the skin with adhesive and may be worn without a bra. Breast forms are available in costume, theatre, and dance supply shops, through online retailers, and at lingerie and underwear shops catering to cisgender women.

BINDING

Binding is a method of compressing breast tissue to achieve a flatter chest profile. Depending on the size of our chest, there are several options that we can use to achieve this. Athletic gear such as sports bras or compression shirts can often be effective. Some people use elastic bandages (commonly known as ACE bandages), although these can sometimes cut off circulation if they are too tight. While it is tempting to bind as tightly as possible to create as flat a chest as possible, it is important to make sure you can still comfortably breathe when binding to avoid health problems.

There are also special garments, called binders, made for both trans and cisgender men with unwanted breast tissue. These binders are very effective, even for those of us with large breasts. They can be purchased online and from some medical supply shops.

BINDING

Hudson is the author of ftmguide.org, a comprehensive information site for trans men and their loved ones, established in 2004.

The term “binding” refers to the process of flattening one’s breast tissue in order to create a male-appearing chest. There is no “one-size-fits all” binding method because everyone is shaped differently, and we all have different levels of comfort with our bodies. Some trans guys don’t bind at all. Some slump or hunch over to hide their chests (which can be very effective but can also cause posture problems over time). Some use different methods of layering clothing to help hide their chests. Some bind only on certain occasions; others bind all the time.

A few binding methods you might consider: layering of shirts; Neoprene waist/abdominal trimmers or back support devices; athletic compression shirts; chest binders/medical compression shirts; or new products designed specifically for FTM binding. Perhaps ironically, it can sometimes be helpful to know your bra and cup size when comparing notes with other trans men on binding solutions. For information about how to calculate this, see ftmguide.org.

Use caution and common sense when binding—if it hurts, cuts your skin, or prevents you from breathing, it is too tight. In the past, trans guys relied on do-it-yourself (DIY) binding solutions because there weren’t any ready-made products available to suit the purpose. Some of these DIY binding methods (like wrapping yourself in Ace bandages or duct tape) are easily accessible, but they aren’t very good for your body, and can even cause serious injury. If you can avoid it, don’t use tape to bind, especially directly on your skin, as it may cut you, cause painful rashes, and pull off layers of skin and hair when removed. It also tends to be too rigid, making it difficult to breathe and move.

Buy the size binder that correlates to your physical measurements. Binders are already designed to be very tight when they fit properly—buying a size too small will be so tight that it may cause severe discomfort or injury. Give yourself a break from binding! The compression on your skin and body from a binder is a lot to take, so don’t bind all day and all night. And when you begin binding, start with just a few hours at a time to let your body get used to it. If a binder’s material doesn’t breathe or wick away sweat, you can end up with sores or rashes on your skin. One way to minimize this risk is to apply a nonirritating body powder to your skin before binding. Another is to wear a thin undershirt beneath your binder that is made of fabric that wicks away sweat. Keep your binders clean.

You might find that the binder you choose tends to roll up in certain areas, particularly around the waist. If this is a problem for you, try sewing an extra length of fabric all the way around the bottom of the binder, and tuck that extra material snugly into your pants. If you find that you have areas of chafing or bulging around the armpit area, you might want to try trimming or otherwise altering that area with a needle and thread. You can often find inexpensive solutions, such as Spandex, Lycra, Velcro, and other materials at your local fabric store, using trial and error to make alterations that suit your specific frame. If you are not handy with a needle and thread, check your local community for a friendly tailor or costume maker who might be able to help you custom fit your binder, or even make a binder from scratch to fit you perfectly.

Finally, if a binder doesn’t work well for you, consider donating it or selling it to another trans man who might have better luck with it.

FACIAL AND BODY HAIR REMOVAL

Facial hair removal can be one of the most difficult components of physical transition. A minority of transgender women have sparse facial hair. However, many of us desire some degree of hair removal. Facial hair will slow with estrogen treatment and testosterone blockade. For some it will be slow and thin enough that we are able to avoid extensive hair removal procedures and perhaps need to shave only every couple of days. Plenty of cisgender women have to deal with unwanted facial hair, and many cisgender women have to regularly shave. Like most things in transition, it is important to consider that all women face internal and external pressures on their bodies and physical appearances.

Most creams, depilatories, and other methods of facial hair removal designed for cisgender women will not work for transgender women. These products are designed to remove the “peach fuzz” (known as villous hair) on cisgender women’s faces. Removing the thicker (terminal) hair on trans women’s faces requires a different approach. Using a method designed for villous hair can even cause injury. Most trans women will either seek electrolysis, laser hair removal, or some combination of the two.

Electrolysis involves inserting a needle-shaped probe into the hair follicle and then using electricity or heat to permanently kill the hair root. The process is slow and painful, but it is permanent. Because of multiple follicles, individual hairs may require several passes until they are gone. We may need as little as 20 or as many as 200 hours of electrolysis to clear our face and be free of shaving. It is a good idea to ask a provider to prescribe an oral pain medicine containing a narcotic as well as a topical anesthetic cream when going through electrolysis. In some cases we may be able to find a hair removal facility where an on-site provider gives anesthetic injections into the face to numb certain areas before electrolysis is performed.

“I have done about 75 hours of facial electrolysis, resulting in the removal of about two-thirds of my beard. The cost so far is almost US$4, 000.”

“I am currently doing electrolysis in the genital area to prepare for GRS. I am also doing electrolysis on my face to remove a few new dark hairs. I expect to spend $2, 000 on electrolysis.”

Another option for removing facial hair is laser hair reduction. It has not been approved by the FDA as a method of permanent hair removal, but it does cause hair reduction. Laser therapy involves using a focused beam of high-energy light whose frequency is “tuned” to the color of the pigments in hair. Because of this, only the pigments receive the light and the surrounding skin and tissues are not affected. When the pigment receives this high-energy light, it rapidly heats and then explodes. Because the laser probe covers more area than an electrolysis probe (about one-half square inch), laser sessions are quicker than electrolysis. Laser can also bring about dramatic results, though there will be some regrowth within a few weeks and many people require ongoing maintenance treatments. Because laser is “tuned” to the colors of dark hairs, people with dark skin or light facial hair are not good laser candidates. Luckily, many people with blonde or red facial hair may not require facial hair removal if they do not mind shaving regularly because they will not develop a “shadow.”

“Am most of the way through [laser] on my face, chest and stomach. Now have very little 5 o’clock shadow and don’t need to cake myself in foundation to feel comfortable passing. Have currently had 7 or 8 sessions at NZ$600 per session. I expect to have another 2 to 3 sessions.”

“At my advanced age, most of the hair was too white to adequately kill off with a laser, so electrolysis was my only option. The results have generally been good, but I am still working on a few stubborn areas. The total cost has been several thousand dollars.”

Electrolysis and laser can both leave our face red and swollen, and sometimes there may be small areas of mild bleeding and crusting or scabs. Ice will help minimize these symptoms, as will tea tree oil applied liberally after the procedure. While laser can be done on someone who is clean-shaven, electrolysis requires a couple of days’ worth of growth so that the tip of the hair can be grasped with forceps. As such, many of us go for electrolysis on Saturday so we can grow our hair for a day before it becomes noticeable, and then have a day for recovery before returning to work Monday morning.

When considering electrolysis or laser hair reduction, make sure to research who will be doing this work. You have only one face and one chance to do it properly. Home systems and excessive discounts should raise suspicion. Proper laser removal centers include a physician medical director who oversees care, and they typically hire registered nurses to operate the equipment. A growing number of LGBTQ health and social centers are beginning to offer such services at a reduced cost. For example, the Mazzoni Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, offers laser hair removal. Primary care providers may also have resources for inexpensive, local trans-friendly hair removal specialists.

PRIVACY

At some point during our transition, many of us begin to desire more privacy around our gender identity, history, or transition. Many of us have an experience of feeling like we have spent so much time focusing on our gender that it has, in some way, taken over our lives. Sometimes we feel tired or bored of talking about gender, or we discover that it is no longer as important to highlight as it had once been. Some of us also shift from feeling like it is important to talk about or disclose our trans identity, status, or experience to feeling like it is not important to highlight. Privacy for some people may include passing or living stealth, while for others it may mean being out in certain contexts and not others.

Being Read Correctly

Most of us would like to be seen in a way that is congruent with our internal identity. This is sometimes called “passing,” being “read the right way,” or not being “clocked.” Many trans people take issue with the concept of “passing,” because it puts the onus on the trans person to prove their legitimacy (Bergman, 2009). Some of us are not read correctly on a consistent basis and wish we were. Others of us take pleasure in looking a little different.

“By nature, I can’t pass. There’s nothing to pass as. So I just dress outrageously and attempt to look as androgynous as possible. My hair is short, my clothes are a punk rock mess, but I’m short and small and my face is feminine, so I’m consistently read as female.”

“I’m not transitioning to another gender, but rather embracing a queered gender identity that defies categories. I am lucky that I have an uncommon name which doesn’t carry a clear gender identity with it, and depending on which culture it is located in, can denote different genders. I’ve not changed that name, but rather happily embraced its ambiguity. In fact, I’ve often wondered how much my name is connected to my gender dysphoria. I certainly hope it is connected, as it is a great name and I much like where I am with my own identity.”

Many of us go through some combination of social, medical, and surgical transitions, changing the way we look, how we behave, and how we interact with others. When we are read correctly, it can make life much easier. Being read correctly is not necessarily the same thing as being stealth. Those of us who are read correctly may be open with many people about our transition history, but we have the option not to talk about it until it comes up naturally, over the course of a conversation or friendship.

Living Stealth

“Stealth” is a common term used to describe the experience of living privately post-transition. Some of us prefer the word “private,” feeling that “stealth” has a quality of sneaking around, or getting away with doing something wrong.

The decision to live privately as a trans person is different for each of us. For most of us, every use of the right pronoun and name is an affirmation of our identity. If we choose not to tell people how we got there, that does not necessarily mean we are ashamed of being trans. It may simply mean that we are living our lives the way we have chosen.

“I no longer feel the need to tell everyone about my past. If they figure it out, I really don’t care, but I’m more concerned with the present.”

For some of us, living stealth may be motivated by the desire for privacy, job or family security, or physical safety. It may be an opportunity to recharge our batteries and live without needing to constantly explain ourselves. Many of us get tired of giving the same answers to the same questions, over and over, as time goes by.

Others of us reach the opposite conclusion, wanting to help bridge the gulf of understanding. Mainstream cultural beliefs about “transness” are so far off the mark that some of us want to be out and visible everywhere we go, to put a face on what “trans” does and does not mean.

“I’m through with addressing the subject in subtle, hushed tones. Give me a damn megaphone and a soapbox, and I’ll parade through the streets screaming it.”

Some of us want to be out, while others desire privacy. Those of us who were activists at the beginning of our transitions may desire more privacy over time. Some of us who desire privacy find that over time we want to focus on activism again. We may come to realize that we just needed a “breather,” to regain our peace of mind and inner resources after spending so much energy on our early transition processes. Many of us donate our time or money to community organizations and choose not to use our own workplace or personal life as an arena for trans activism.

THE SHOWER

Nyah Harwood is a queer trans woman. She lives in Cairns, Australia. She is currently engaged in her honors year in cultural studies at Southern Cross University. Her research examines the biopolitics of administrative classifications of sex and gender in Australia. Her interests are strongly focused on critical trans politics and trans feminism, as well as antioppression, harm reduction, and sex work politics.

My housemates don’t know that I am trans. At least, I haven’t “come out” to them. I make a point of raising my voice just that little bit higher when I’m talking to them. I walk around the house with my chest poked just that little bit further out. I hold my head up high, but low enough to hide my Adam’s apple. As much as I pride myself on gender fucking and confusing people, I am constrained by my need to protect myself.

I am standing naked in the bathroom of my house, waiting for the shower to warm up. The doorknob turns, and the door opens. I realize I forgot to lock the door. I can see my housemate standing in the doorway and she can see me. I don’t think anything of it at first, but then, suddenly, internalized cissexism kick-starts my shame and I realize once again not just that I am naked but also what my body means. In this moment, as all around the world gender wreaks violent havoc on unknowing, unwilling bodies, my trans body materializes that violence in my bathroom for my housemate to see. “Welcome to the world of nonnormative gender!”

I am situated in a space between knowing and feeling—I feel shame, though I know I shouldn’t. It’s a familiar feeling, once again—the tensing of my muscles, the flushing of my face, the nervousness. I panic. As if through instinct, my arms tense and my hands move together down toward my crotch to hide my penis, leaving only my estrogenated breasts visible. That’s right, I remember now: I am a liability.

My housemate and I say an awkward “oops.” The door shuts as quickly as it was opened, and we go back to our business. But I can’t simply return. I feel illegitimate. I want to explain myself to others. To warn them even: “My body is a fucking weapon.” I keep telling myself how fucking transgressive I am; but a moment later I am crying from the shame I feel. I am the embodiment of a constant tension between legitimacy and illegitimacy, invisibility and transgression, and the potential ridicule, violence, or death that comes with being “seen,” or not being seen at all.

Challenges to Keeping Our Privacy

There are practical reasons that living completely privately may not be a realistic goal. The power of the Internet, coupled with post-9/11 security laws, makes it impossible to live with certainty that our old legal identity is permanently inaccessible to others.

Even for those of us who are long into a physical transition and living privately, events such as looking for a new job can lead others to discover our gender histories. A background check, listing references on a resume, listing schools we attended—any of these may lead a prospective employer to our old identity. We can ask references to respect our transition and use our new name and preferred pronoun, choosing to drop from our resume those who refuse or are unreliable, and we may be able to get our school transcripts changed to reflect our new identity. However, none of these strategies is foolproof.

When someone misreads our gender, or identifies us as trans, it can be easy to beat ourselves up, thinking that we should be better at being who we are, or to feel anxious about what that misreading means. Knowing where those judgments are coming from and balancing what it takes to feel good while avoiding putting too much pressure on ourselves can be tricky. It is easy to set up an unattainable goal of passing all of the time.

Online Privacy

It can be challenging to completely eliminate our online presence. Any information about our past that appears online—from news stories that identify us as a particular gender to public records of our name changes to blog posts and social media sites—is archived somewhere and may be accessible to others. Our digital footprints are increasingly difficult to erase, and the dense connections between friends, family, and colleagues online can blur the boundaries between these groups, providing opportunities for accidental disclosure to those we would prefer not to tell. There are a few things we can do to secure our online privacy as much as possible:

• Consider using a pseudonym, nickname, or other unofficial name online. While those who know us in real life may have access to these sites, this will ensure that we are not “searchable” by potential employers, colleagues, or college admission officers with whom we do not choose to share this information. There are many examples of successful individuals who have built strong online communities, brands, and careers using a name that is not their own. However, be aware that once you have built a community or presence with a pseudonym, it is possible that it may be difficult to reconcile this with your real name later on. For example, some important contacts may not recognize your real name.

• Understand and use the privacy settings on social networks. Most social networks allow us to restrict access to our accounts, entirely, to the general public, or to specific groups of people who can see certain types of information. Know what you are sharing, who can see it, and consider the potential risks if all of the information were to become public. Once information is put online, it can be easily shared with others, either intentionally or accidentally.

• Monitor your online reputation. Conduct online searches for your name(s) on a regular basis. It is unlikely that you will be able to have everyone remove information you do not like, but knowing what is out there can be helpful in knowing how to discuss the information with others who are likely to look you up.

As trans people, we take many different approaches to privacy in our lives. Some of us live completely stealth, while others of us are open as much as possible about our identities. Most of us fall somewhere in between. Whether we choose to live more private or more open lives, we all struggle with making sure that we have as much control as possible over how we do this.

Transitioning as a Public Process

The people we see on the street every day and at work and school are going to notice over time if we begin living in a new gender role. For those of us who choose to transition to live full-time in a new gender, our transition becomes a public process unless we leave everything we know behind.

Many of us who physically transition desire privacy but are remaining in the same communities. This can lead to a longing to just “be,” to find groups and spaces where the transition is not an automatic focus.

“So many people already know that I think most people that I meet are likely to find out rather quickly. It has made me long for a masculine space where no one knows. A separate group of guy friends I can be stealth with.”

People are going to have different reactions to our transition. Some may be confused or even hostile, while others may be accepting but afraid to bring it up. We may try out living in our new gender by dressing in it at first only when going on trips out of town or to places where we are not known.

Most of us go through gradual changes and live in a gray area for some time, where sometimes we are recognized in our affirmed gender and sometimes we are not. If we remain in our communities, we often have to deal with them knowing our past. However, we also have the benefit of being near people who (hopefully) love, support, and nurture us.

LEARNING NEW GENDER RULES

One area of transitioning that can be particularly bewildering for many of us is dealing with the new stereotypes and expectations that come with living in our affirmed gender. Some of us welcome the changes. However, these changes can also be confusing and surprising. Acting the same way we have always acted may be read very differently now than it was when we were living as our birth-assigned gender.

Some arenas in which we may run into gendered expectations include social situations with colleagues or friend groups and dating situations. Rules govern how men and women interact in public spaces. Some are more obvious, such as rules about holding doors and shaking hands. Others are more subtle. Men are typically expected to be more aggressive and women less so. It is easier for women to come off as pushy than it is for men. Women are expected to smile more. Women can generally smile at or wave at young children, while men may be suspect for this behavior.

Groups of men and groups of women may act differently when they are alone. We are sometimes surprised or shocked to find out what happens in groups that we had not been a part of until now.

“Man talk was a very strange discovery. Men do not talk the same way if there are any female people in the room, but as soon as women leave the room there is a strange shift in the tone, the body language, the subject of conversation.”

“Men act different when they are in a group without women around. Men also tend to ‘give each other a hard time’ and it is seen as affection. I had to learn to not take verbal jokes to me so seriously and instead of getting my feelings hurt just make sure I laughed it off and had a good comeback.”

“It’s been a lot easier than I thought making friends with other women and being more socially active with them.”

“I attended a Men’s only recovery group and I was amazed at how much these men talked about their feelings. They also talked about feeling oppressed by society by being told they had to be a good provider financially, be good with tools, and that they should not show fear. Outside of that very emotional group they went right back to ‘being guys.’ Talking about cars, women, hunting, etc.”

There are often things people expect us to know by virtue of being a man or a woman.

“When I was female, and throughout the gray area, I always had friends cut my hair, because if I went somewhere and got it cut it was always too girly. I went to a barbershop as a guy for the first time a few months ago and they asked me, ‘How do you usually tell the barber to cut it?’ I had no idea. I didn’t even know the kind of language I was supposed to use, and I felt even more awkward because I knew that most men have this as part of their cultural knowledge from very early on.”

“As a single mother, nothing I did was ever good enough and I was treated like shit for having bred at such a young age. As a single dad, I’m a hero and it’s so awesome that I’m there for the kid.”

“It is often frustrating being pigeon-holed and misunderstood because everyone in our culture expects certain traits from women that I am hard-pressed to exhibit. I realize this speaks more to culture than to my transgenderedness but still, it constrains. Perhaps it is more of a plain feminist issue.”

“Being seen socially as male is strange occasionally because I am now viewed as an automatic expert in certain areas based on my age and gender, and all of a sudden no longer an assumed expert in matching colors of rooms to curtains or advising about fashion. Yet somehow in all this gender changing I kept my knowledge of proper color combinations and cooking and didn’t get the manual on cars, electronics, small appliances, and plumbing. Is there someone I can trade with? Someone out there who desperately wants the book on cooking and fashion and can trade for the car/electronics/repair manual I seem to have lost?”

The way we flirt with others and they flirt with us may change.

“The unforeseen was to have men open doors for me or stare at my breasts while talking to me. That took a little to get used to.”

Our sexuality is sometimes perceived differently by others depending on our gender presentation. Trans men are often perceived as gay because they may have more stereotypically feminine hand gestures or vocal inflections.

“Social interactions as a guy are strange. Generally I think I am accepted as a gay guy within straight male spaces—straight bars, bathrooms, etc.—which is fine with me and makes being different a little easier.”

The existence of stereotypical gender roles does not mean that we need to fulfill all those expectations. In fact, very few people do. As trans people, we have many different ideas about gender roles, how we want to be treated as gendered beings, and what gender justice looks like to us. Identify for yourself your sense of what people are projecting onto you about your gender and how they expect you to act because of it. Evaluate your values and ethics around gender equality and try on different ways of being in your new gender. Figure out how to be your best self in your gender and how to be yourself in a way that is in line with your values and visions for how the world should treat people of all genders. Find other people who are wrestling with similar questions, challenge expectations of your gender that you do not accept, and celebrate the aspects of your gender presentation and experience that you love most.

TRANS PEOPLE AND PRISON

Colby Lenz, a volunteer organizer for the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP), provides an introduction to incarceration in trans communities.

Who is in prison? People whose genders do not conform to fixed gender categories are targeted by police and state violence and overly represented in jails, prisons, detention centers, mental health lock-ups, and all kinds of youth lock-ups. I use the term “lock-ups” here to describe this range of systems that cage people.

Why are so many transgender and gender-variant people locked up? Transgender, gender-variant, and intersex people, especially poor people and people of color, face discrimination from early on in life and have significantly decreased chances of avoiding cycles of poverty and incarceration. Facing discrimination, transgender people are pushed out of legal economies. In the United States, criminal punishment systems masquerade as solutions to violence, poverty, addiction, and illness but only add violence, addiction, poverty, and illness. Many gender nonconforming youth are pushed onto the streets or into out-of-home care or youth lock-ups because of discrimination, violence, and a lack of family support.

What is the impact on people’s lives inside and outside of these lock-ups? Transgender and gender-variant people trying to survive in lock-ups face increased violence and severe neglect. Because most of these systems are sex segregated, transgender people whose genders don’t match their birth sex are often denied access to services or do get access—only to face more harassment and violence. Transgender and gender-variant people in lock-ups face more time in segregation, whether by outright discrimination or as a violent form of “protection.” Transgender people in lock-ups face early illness and death because they lack access to health care or are outright denied health care. People in lock-ups continue to fight for access to hormones and other transgender health care needs. People struggle for access to clothes that fit their gender and permission to wear them (i.e., boxers, bras). Transgender people are also made more vulnerable to harm and death because of the lack of protection from violence in lock-ups, including sexual violence. Official protections do little to increase safety for transgender people since guards often commit or instigate the violence.

How can we fight against lock-ups? For those living outside of lock-ups, we see our community members constantly ripped away from our communities. Because transgender people are so heavily policed and incarcerated, organizing against this policing and incarceration is all the more complicated. Despite these challenges (and many more), our communities continue to rise and survive! We don’t need more cages; we need real resources and opportunities—to heal and to thrive, and to build power together to end poverty, violence, and all kinds of incarceration. For examples of organizations led by people who have survived time locked-up and fighting for collective liberation, see the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP), the Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP), Black & Pink, CCWP, and BreakOUT!

WHEN OUR IDENTITIES CHANGE

Not all trans identities are static. Some are, of course—when some of us transition, that is it: We settle into our gender identity, and it remains fairly stable throughout our lives. For many people, though, gender is more of a constant, evolving identity. We might find that, even after what we thought was a “complete” transition, there are parts of our identity that are still shifting. Perhaps these are small things—changes in the range of appearance, style, or activities we feel comfortable embracing as part of our gender expression. Or perhaps they are larger, more substantive changes in our gender identity itself. If you find your gender identity shifting, allow yourself the space and freedom you need to try to understand your evolving gender identity.

When gender identities shift after an initial transition, many of us begin to question why we feel the way we do. We may echo the negative feedback we have received from others, asking ourselves whether others were right all along, or whether we are just confused. However, there is no limit on the number of times we are allowed to reevaluate our identities, rethink how we would like to be perceived, or reinvent ourselves.

It may also be the case that our particular gender identity just shifts over time. This is OK. Recognizing these shifts and nuances will help us to more authentically be ourselves.

It can be helpful to look at other people in our lives to see how their gender identities or presentations change over time. Many cisgender people shift their gender presentation over time—it is a normal part of growing into being who we are. Remember that gender is only one piece of our whole selves—our community, our economic situation, our relationships, and our family can also play a role in shaping the range of identities, opportunities, and expressions we choose.

People who transition multiple times might use different words to describe their experiences. Some might identify as transgender, gender-variant, or gender nonconforming. Others will not. Some of us use words like “detransition,” “peel,” “retransition,” or “transition again” to describe our experiences.

If you are a person who has transitioned and are now having new and complicated questions and thoughts about your gender identity, try to find a supportive person in your community who can help you work through these questions.

If you have someone in your life who is facing these questions, find ways to support and understand them. Sometimes people want to ask us questions about our medical status, like “Do you regret going on hormones or having surgery?” Trans people have many different identities, needs, experiences, and body configurations. A change in our gender identity or expression does not necessarily mean we are unhappy with the changes we have made so far. Regret is not the only (or even the main) reason we may continue to question or change our identity after transitioning.

INTERVIEW WITH KRYS SHELLEY

Krys Shelley is 30 years old and lives in Los Angeles, California.

Colby Lenz: What was your experience in a women’s prison as someone who doesn’t fit gender stereotypes?

Krys Shelley: Well, the first thing they do when you get to prison is strip search you and force you to wear a dress that’s like a gown your grandma might wear. I found that so humiliating and discriminating. You have to get naked and then wear that dress for hours. Then later, if your room got seriously searched, even if you weren’t the main focus, they forced you back into a dress and cuffed you. And if you weren’t in compliance by wearing that dress, they would attack you more. Even if you meant no disrespect, you were just so uncomfortable.

We were fighting to change this before I left Valley State Prison for Women, but the fight ended when they crowded everyone from that prison into the women’s prison across the street. They would also make us wear women’s underwear and cone bras. We were fighting to be able to wear boxers and sports bras, because they don’t accommodate people who are different, only who they decide a “woman” is or should be.

Colby: How did the guards and other staff in prison treat you?

Krys: I definitely faced more discrimination because I look different. I was seen as a man and so they treated me like a man in terms of how aggressive they were. Basically the guards would get away with whatever they could, like saying something stupid about my gender to try to get me to react. The harassment I faced was more verbal than physical, but it did get physical more than once. The guards attacked me because they read me as aggressive because I look masculine, and I think they were threatened by me. They messed with me because of the way I dress, my physical appearance, because of the way I choose to be. Just like the real world, they mess with you out there and in prison; it’s just more intense in there because they can legally do it.

Colby: How did you and other gender nonconforming people you know support each other in prison?

Krys: People definitely organized and supported each other, but of course we weren’t always united. One thing we did was file complaints about harassment. We tried to file those as class actions, but the prison system changed the policy to block us from doing this. We also had a Two-Spirit Circle for people with nonconforming gender or people who identified as male or having a lot of masculinity. We would get together and talk about problems we were having. People were equal in the circle but one person organized and united us. We all respected each other and talked with each other and not at each other. It helped us survive in there.

SELF-CARE AND SELF-EFFICACY

As we struggle to keep up in our daily lives, it is easy to forget to take care of ourselves. This is an important part of life, and during a transition, it can be particularly vital to make a habit of practicing good self-care. Even in the best of circumstances, a transition means a lot of upheaval and change in our lives. Remember to spend time doing things that make you feel good, and that are good for you. See Chapters 5 and 14 for more information on self-care.

The flip side of self-care is self-efficacy. This term means remembering that we are able to affect the world around us. It can be easy for some of us to develop a sense of victimhood or carrying a burden that we did not ask for. The world can be a hard place for us to navigate, and while self-focused habits and routines are an important part of a healthy life, it can be incredibly powerful to take control of other parts of our lives as well. We can make good things happen, for ourselves and others.

Nurturing our Interests and Passions

As trans people, we often spend much of our time, especially while actively transitioning, thinking about transition and focusing on gender. However, we all have other parts of ourselves that are not directly related to our gender identity or experience.

Some communities we are involved in include artistic communities such as visual art, dance, music, performance art, DJ-ing, and filmmaking; political and activist communities that pursue social change; cultural communities based on our cultural experiences; professional associations and networks; and activity groups, like reading or knitting groups. We may be interested in assisting with our local senatorial race campaign, doing HIV and STI prevention work in our community, or joining an area coalition of feminists who support women’s rights. We may be interested in silent films, spoken word, or our local music scene. Whatever our interests are, nurturing them can offer potential for meeting caring and supportive people.

“My community life is not as rich as it has been at other times in my life, because I’m a middle-aged college professor with two kids, one a babe in arms, and I don’t get out at night as much as I would like. Still I have a number of sustaining friendships that fill a community function for me. Many of these have academic origins, oddly—people I’ve met through queer theoretical networks, or at my local LGBT historical society. And many of these people are busy middle-aged professionals like me. When I see them, it’s at work-related events more often than not, and the rest of the time my contact with them is online or on the phone. Earlier in my life I was a very active member of an SM/leather community in San Francisco that overlapped with a genderqueer/trans community. That scene was very different! It couldn’t have been more embodied and fleshy—it was fabulous, challenging, scintillating with the excitement of self-creation and the joy of discovering expansive possibilities.”

For some people, being out as transgender or gender nonconforming is essential to their participation in other communities, while for others, their trans status may not feel connected or relevant. There is no “right” way to be trans, and there are no rules about whether, or how, to disclose our gender identity. Making the decision that is right for us in building the types of relationships we want to build is most important.

Finding Trans Community

The past decade has seen an explosion in the number and variety of resources that are available for trans people in the United States, both regionally and nationally. While it is certainly true that our access to other trans people varies widely based on where we live—it might be a few stops on the train or hundreds of miles by bus or car—there are more options out there than there have ever been for connecting with other trans people.

Trans social groups offer support in transition and in the day-to-day issues that come up as a trans person. They may also give us a chance to engage in activism to address transphobia and advocacy to get the kinds of care and resources that we need. Support groups may allow us to channel our creativity through balls, parties, pageants, and art shows. Finding a group that fits our particular needs may take a little time, but it can also be a rewarding experience that helps us build a community that includes people with shared experiences. Some people find this to be an indispensable part of their trans experience, while it is less meaningful to others. As with everything else, it is important to spend time figuring out what types of social support we need so that we are more able to find the best resources.

Trans groups and organizations take many forms. Some are gender-specific (trans women, trans men, gender-variant/genderqueer people); some are for specific identities or experiences (trans people of color, Two-Spirit people, trans people with disabilities, trans parents); and some are a mix of everything. There are also many groups specifically for young people, such as Queer Youth Seattle, the Transgender Youth Drop-In Center (Chicago), and the Attic Youth Center (Philadelphia). There are online support groups, like Laura’s place; local and regional groups, like Tri-Ess chapters around the United States, TransGuyzPDX in Portland, Oregon, TransJustice at the Audre Lorde Project in New York City, Trans & Friends Transitionz by Feminist Outlawz in Atlanta, Georgia; state-wide organizing groups, like the Connecticut Trans Advocacy Coalition; national groups like the National Center for Transgender Equality; and annual events and conferences, like Gender Odyssey in Seattle and the Philadelphia Trans Health Conference.

There are also many groups and organizations that serve specific communities within the larger trans community. Groups like the Transgender Justice in Prison Group and Hearts on a Wire provide support for trans people who are currently or formerly incarcerated, through letter-writing, advocacy, and policy work. Organizations like Southerners on New Ground (SONG) in the South and GenderJustice in Los Angeles offer space for multiissue community organizing. Many HIV/AIDS service organizations throughout the country have specific programs for transgender and gender nonconforming people that address HIV prevention, as well as related social and political issues.

Finding a group that is right for you might take a couple of tries. Perhaps the discussion is not quite what you thought it would be, or the other participants are not exactly who you were anticipating. Challenging yourself to continue to put yourself out there can be a rewarding experience. If the group you attend is simply not right for you, ask someone there if they have other ideas of places to go in your area. Try not to be discouraged if your first visits are not exactly what you are looking for—relationships can take some time to build. Meeting just one person you connect with is a huge success, because it will give you a place to grow from. You might find that your supportive community comes out of that one connection.

“I’ve found it’s really hard to form a cohesive transgender community from nothing. If these things don’t coalesce on their own, they tend to fall victim to infighting and anger, possibly because trans phenomena cut across so many other identities and intersect with so many privileges and marginalizations. That said, I find the trans and genderqueer people with whom I am acquainted to be wonderful folks. They’re fun to hang around with and talk to and don’t generally freak out when I get radically counter-cultural in the middle of a McDonald’s. Of course, there’s the issue: The people with whom I am acquainted are not the only trans people out there, and often a specific trans-centered support group draws in an older crowd with a different view of trans issues informed by the communities of the ’70s and ’80s. That view is often incompatible with the views of trans people who came to understand themselves in a post-queer-revolution world.”

Online social networks like Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter offer trans people a wide range of opportunities to connect with one another. Email lists and Yahoo/Google groups similarly offer various ways for trans people connect with one another and share resources and personal stories. For example, the Dina List is an email list made up of Orthodox Jewish transgender people.

Online resource lists are useful first steps in finding current groups in our city, state, or region. One word about online resource lists is that the Web sites they are found on are not always kept up to date, and there is not currently one comprehensive list of all trans support resources available in the United States.

Sports

Sports and athletics are often an important part of our lives. They can have a hugely positive effect on us, including the health and mental health benefits of exercise; providing social community among our teammates, competitors, and fans; developing leadership and collaboration skills through teamwork; and giving us opportunities to build skills through practice, hard work, and perseverance. Because of these broad benefits, the growth of opportunities for cisgender women to participate in sports has been linked to their growing achievements in the workplace and society, in general. As trans people become a more visible and vocal part of communities, we are asserting our right to access sports as well.