Zuni Two-Spirit person in photo titled, “We-Wa, a Zuni berdache, weaving” (John K. Hillers, 1843–1925, photographer, Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology, ca. 1871–ca. 1907).

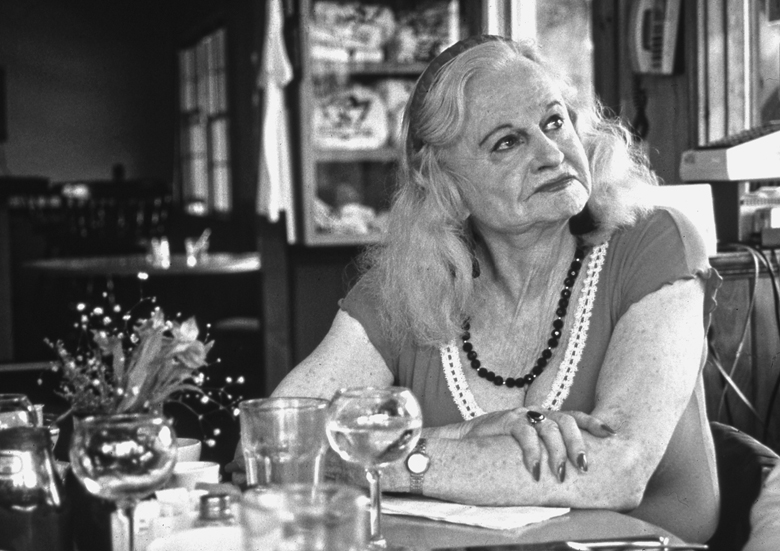

Genny Beemyn

GENDER NONCONFORMING INDIVIDUALS have been documented in many different cultures and eras. But can there be said to be a “transgender history,” when “transgender” is a contemporary term and when individuals in past centuries who would perhaps appear to be transgender from our vantage point might not have conceptualized their lives in such a way? And what about individuals today who have the ability to describe themselves as transgender but choose not to for a variety of reasons, including the perception that it is a white, middle-class Western term or that it implies transitioning from one gender to another? Should they be left out of “transgender history” because they do not specifically identify as transgender?

Historians have often ignored or dismissed instances of nonnormative gender expression, especially among individuals assigned female at birth, who were regarded as simply seeking male privilege if they lived as men. It was not until lesbian and gay historians in the 1970s and 1980s sought to identify and celebrate individuals from the past who had had same-sex relationships that gender nonconforming individuals began to receive more than cursory attention. However, in their attempts to normalize same-sex sexuality by showing that people attracted to others of the same sex existed across time and cultures, many of these historians assumed that anyone who cross-dressed or lived as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth did so in order to pursue same-sex relationships. Many transgender people have begun to call attention to our own history, pointing to evidence that many of these individuals were not motivated primarily by same-sex attraction (Califia, 1997, p. 121).

These questions complicate any attempt to write a transgender history. While it would be inappropriate to limit transgender history to people who lived at a time and place when the concept of “transgender” was available and used by them, it would also be inappropriate to assume that people who are “transgender,” as we currently understand the term, existed throughout history. For this reason, we should not claim that gender nonconforming individuals were “transgender” or “transsexual” if these categories were not yet named or yet to be embraced.

Another difficulty in writing transgender history is that people in the past may have presented as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth for reasons other than a sense of gender difference. For example, female-assigned individuals may have presented as men in order to escape restrictive gender roles, and both women and men may have lived cross-gender lives to pursue same-sex sexual relationships.

A scholar who has sought to address this issue is anthropologist Jason Cromwell (1999). He devised three questions for researchers to consider in trying to determine whether female-assigned individuals from the past who presented as male might have been what we would call “transsexual” today: If the individuals indicated that they were men, if they attempted to modify their bodies to look more traditionally male, and if they tried to live their lives as men, keeping the knowledge of their female bodies a secret, even if it meant dying rather than seeking necessary medical care.

Cromwell’s approach can also be used for individuals assigned male at birth who presented as female. But his questions do not address the differences between transsexual people and individuals we now refer to as cross-dressers. To make this distinction, two other questions can be asked: If the individuals continued to cross-dress when it was publicly known that they cross-dressed or if they cross-dressed consistently but only in private, so that no one else knew, except perhaps their families. In either case, the important factor is that the people who cross-dressed did not receive any advantage or benefit from doing so, other than their own comfort and satisfaction.

The European nations that colonized what is today the United States rejected and often punished perceived instances of gender nonconformity. But many Native American cultures at the time of European conquest welcomed and had recognized roles for individuals who assumed behaviors and identities different from those of the gender assigned to them at birth. These cultures enabled male-assigned individuals and, to a lesser extent, female-assigned individuals to dress, work, and live, either partially or completely, as a different gender.

One person cited by anthropologist Jason Cromwell who fits the criteria of a trans person in history is Billy Tipton, a jazz musician who lived as a man for more than 50 years and who was not discovered to have been assigned female until his death in 1989. Tipton apparently turned away from what could have been his big break in the music industry for fear that the exposure would “out” him. He also avoided doctors and died from a treatable medical condition, rather than risk disclosure.

Spanish conquistador Cabeza de Vaca wrote one of the earliest known descriptions of gender nonconforming individuals in Native American society. In the 1530s, he described seeing, among a group of Coahuiltecan Indians in what is today Southern Texas, “effeminate, impotent men” who are married to other men and “go about covered-up like women and they do the work of women” (Lang, 1998, p. 67).

Zuni Two-Spirit person in photo titled, “We-Wa, a Zuni berdache, weaving” (John K. Hillers, 1843–1925, photographer, Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology, ca. 1871–ca. 1907).

Like de Vaca, most of those who reported on gender diversity in Native American cultures were Europeans—conquistadors, explorers, missionaries, or traders—whose worldviews were shaped by Christian doctrines that espoused adherence to strict gender roles and condemned any expressions of sexuality outside of married male-female relationships. Consequently, they reacted to instances of nonbinary genders, in the words of gay scholar Will Roscoe (1998), “with amazement, dismay, disgust, and occasionally, when they weren’t dependent on the natives’ goodwill, with violence” (p. 4).

A less judgmental account was provided by Edwin T. Denig, a mid-19th-century fur trader in present-day Montana, who expressed astonishment at the Crow Indians’ acceptance of a “neuter” gender. “Strange country this,” he stated, “where males assume the dress and perform the duties of females, while women turn men and mate with their own sex!” (Roscoe, 1998, p. 3). Another matter-of-fact narrative was provided by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, an artist who accompanied a French expedition to Florida in 1564, who noted that what he referred to as “hermaphrodites” were “quite common” among the Timucua Indians (Katz, 1976, p. 287).

At the other extreme was the reaction of Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa. In his trek across the Isthmus of Panama in 1513, Balboa set his troop’s dogs on 40 male-assigned Cueva Indians for being “sodomites,” as they had assumed the roles of women. Another Spanish conquistador, Nuño de Guzmán, burned alive a male-assigned individual who presented as female—considering the person to be a male prostitute—while traveling through Mexico in the 1530s (Saslow, 1999).

As these different accounts indicate, Europeans did not agree on what to make of cultures that recognized nonbinary genders. Lacking comparable institutional roles in their own societies, they labeled the aspects that seemed familiar to them: Male-assigned individuals engaged in same-sex sexual behavior (“sodomites”) or individuals that combined male and female elements (“hermaphrodites”). Anthropologists and historians in the 20th century would repeat the same mistake, interpreting these individuals as “homosexuals,” “transvestites,” or “berdaches” (a French adaptation of the Arabic word for a male prostitute or a young male slave used for sexual purposes) (Roscoe, 1987).

While male-assigned individuals who assumed female roles often married other male-assigned individuals, their partners presented as masculine and the relationships were generally not viewed in Native American cultures as involving two people of the same gender. The same was true of female-assigned individuals who assumed male roles and married other female-assigned individuals. Because many Native American groups recognized genders beyond male and female, these relationships would better be categorized as what anthropologist Sabine Lang (1999, p. 98) calls “hetero-gender” relationships—not as “same-sex” relationships, as they were often described by European and Euro-American writers from the 17th through the late 20th centuries.

By failing to see beyond their own biases and prejudices, these observers mischaracterized the Native American societies that accepted gender diversity. Within most Native American cultures, male- and female-assigned individuals who assumed different genders were not considered to be women or men; rather, they constituted separate genders that combined female and male elements. This fact is reflected in the words that Native American groups developed to describe multiple genders. For example, the terms for male-assigned individuals who took on female roles used by the Cheyenne (heemaneh), the Ojibwa (agokwa), and the Yuki (i-wa-musp) translate as “half men, half women,” or “men-women.” Other Native American groups referred to male-assigned individuals who “dress as a woman,” “act like a woman,” or were a “would-be woman” (Lang, 1998). Similarly, the Zuni called a female-assigned individual who took on male roles a katsotse, or “boy-girl” (Lang, 1999).

Individuals who assumed different genders were apparently accepted in most of the Native American societies in which they have been known to exist, but their statuses and roles differed from group to group and over time. Some Native American cultures considered them to possess supernatural powers and afforded them special ceremonial roles; in other cultures, they were less revered and viewed more secularly (Lang, 1998). In these societies, the status of individuals who assumed different genders seems to have reflected their gender role, rather than a special gender status. If women predominated in particular occupations, such as being healers, shamans, and handcrafters, then male-assigned individuals who took on female roles engaged in the same professions. In a similar way, the female-assigned individuals who took on male roles became hunters and warriors (Lang, 1999).

Just as the cultural status of individuals who assumed different genders seems to have varied greatly, so too did the extent to which they took on these roles. Some adopted male or female roles completely, others only partly or part of the time. In some cases, dressing as a different gender was central to assuming the gender role; in others, it was not. Marrying or having relationships with other male-assigned or other female-assigned individuals was likewise common in some cultures but less so in others. “Gender variance is as diverse as Native American cultures themselves,” writes Sabine Lang, (1999). “About the only common denominator is that in many Native American tribal cultures systems of multiple genders existed” (pp. 95–96).

The cultural inclusion of individuals who assumed different genders in some Native American societies stands in contrast to the general lack of recognition within the white-dominated American colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries. To the extent that individuals who cross-dressed or who lived as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth were acknowledged in the colonies, it was largely to condemn their behavior as unnatural and sinful. For example, when Mary Henly, a female-assigned individual in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, was arrested in 1692 for wearing “men’s clothing,” the charges stated that such behavior was “seeming to confound the course of nature” (Reis, 2007, p. 152).

One of the first recorded examples of a gender nonconforming individual in colonial America involved a Virginia servant who claimed to be both a man and a woman and, at different times, adopted the traditional roles and clothing of men and women and variously went by the names of Thomas and Thomasine Hall. Unable to establish Hall’s “true” gender, despite repeated physical examinations, and unsure of whether to punish him or her for wearing men’s or women’s apparel, local citizens asked the court at Jamestown to resolve the issue.

Perhaps because it took Hall at his or her word that he or she was bigendered (what we would call intersex today), the court ordered Hall in 1629 to wear both a man’s breeches and a woman’s apron and cap. In a sense, this unique ruling affirmed Hall’s dual nature and subverted traditional gender categories. But by fixing Hall’s gender and denying him or her the freedom to switch between male and female identities, the decision punished Hall and reinforced gender boundaries (Brown, 1995; Reis, 2007; Rupp, 1999).

Relatively few instances of gender nonconformity are documented in the colonial and postcolonial periods. A number of the cases that became known involved female-assigned individuals who lived as men and whose birth gender was discovered only when their bodies were examined following an injury or death. Fewer examples of male-assigned individuals who lived as women are recorded, perhaps because they had less ability to present effectively as female due to their facial hair and physiques.

The lack of a public presence for individuals who assumed different genders began to change in the mid-19th century, as a growing number of single people left their communities of origin to earn a living, gain greater freedom, or simply see the world. Able to take advantage of the anonymity afforded by new surroundings, these migrants had greater opportunities to fashion their own lives, which for some meant presenting as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth.

Some headed out West, where, according to historian Peter Boag (2011), “crossdressers were not simply ubiquitous, but were very much a part of daily life on the frontier” (pp. 1–2). The industrialization of US cities led others to move from rural to urban areas, where individuals who lived different gendered lives created community spaces in which they could meet and socialize with others like themselves. The most popular of these gathering places were masquerade balls, or “drags” as they were commonly known. One of the earliest known drags took place in Washington, D.C., on New Year’s Eve in 1885. The event was documented by the Washington Evening Star because a participant, “Miss Maud,” was arrested while returning home the following morning. Dressed in “a pink dress trimmed with white lace, with stockings and undergarments to match,” the 30-year-old male-assigned black participant was charged with vagrancy and sentenced to three months in jail, even though the judge, the newspaper reported, “admired his stylish appearance” (Roscoe, 1991, p. 240).

The growing visibility of male-assigned individuals who presented as female in the late 19th century was not limited to Washington. By the 1890s, female-presenting cross-dressers had also begun organizing drag events in New York City. These drags drew enormous numbers of black and white participants and spectators, especially during the late 1920s and early 1930s, when at least a half dozen events were staged each year in some of the city’s largest venues, including Madison Square Garden (Chauncey, 1994). By 1930, public drag balls were also being held in Chicago, New Orleans, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and other US cities, bringing together hundreds of cross-dressing individuals and their escorts, and often an equal or greater number of curious onlookers (Anonymous, 1933; Drexel, 1997; Matthews, 1927). Organizers typically obtained a license from the police to prevent participants from being arrested for violating ordinances against cross-dressing.

While female-assigned individuals who presented as male did not hold drag balls in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were by no means invisible in society. Some performed as male impersonators to entertain audiences, while others cross-dressed both on and off stage. One of the most notable cross-dressers was Gladys Bentley, a black blues singer and pianist who became well known during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. Bentley, an open lesbian, performed in a white tuxedo and top hat and regularly wore “men’s” clothing out in public with her female partner (Garber, 1988).

Another indication of the growing presence of individuals who assumed gender behaviors and identities different from the gender assigned to them at birth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the interest that US and European physicians began to show in their experiences. Many of these sexologists, as they became known, did not make clear distinctions between gender nonconformity and same-sex attraction. Rather than treating same-sex sexuality as a separate category, they considered it only a sign of “gender inversion”—that is, having a gender inverted or opposite of the gender assigned to the person at birth. One of the leading advocates of this theory was Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a German lawyer who wrote in the 1860s that his own interest in other men resulted from having “a female soul enclosed within a male body” (Meyerowitz, 2002; Rupp, 1999; Stryker, 2008, p. 37).

The sexologist who had the greatest influence on the Western medical profession’s views toward sexual and gender difference in the late 19th century was Austro-German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing. In his widely cited study, Psychopathia Sexualis, which was first published in 1886, Krafft-Ebing created a framework of increasing severity of cross-gender identification (and, in his view, increasing pathology). The range went from individuals who had a strong preference for clothing of the “other sex,” to individuals whose feelings and inclinations were considered more appropriate for someone of the “other sex,” to individuals who believed themselves to be the “other sex” and who claimed that the sex assigned to them at birth was wrong (Heidenreich, 1997, p. 270; Stryker, 2008; von Krafft-Ebing, 2006).

Not until the early 20th century did gender difference become considered a separate phenomenon from same-sex sexuality and start to be less pathologized by the medical profession. In his pioneering 1910 work Transvestites, German physician and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld coined the word “transvestite”—from the Latin “trans” or “across” and “vestis” or “clothing”—to refer to individuals who are overcome with a “feeling of peace, security and exaltation, happiness and well-being...when in the clothing of the other sex” (p. 125).

Hirschfeld (1991 [1910]) saw cross-dressing as completely distinct from “homosexuality,” a term that began to be commonly used in the medical literature in the early 20th century to categorize individuals who were attracted to others of the same sex. Through his research, Hirschfeld, who was homosexual himself, not only found that transvestites could be of any sexual orientation (including asexual) but also that most he met were heterosexual from the standpoint of their gender assigned at birth. In his study of 17 individuals who cross-dressed, he considered none to be homosexual and “at the most” one—the lone female-assigned person in his sample—to be bisexual.

It is significant that Hirschfeld included a female-assigned person in his study, as most researchers, before and after him, considered cross-dressing to be an exclusively male phenomenon. Also unlike other medical writers, especially psychoanalysts, Hirschfeld recognized that cross-dressers were not suffering from a form of psychopathology, nor were they masochists or fetishists. While some derived erotic pleasure from cross-dressing, not all did, and Hirschfeld was not convinced that it was a necessary part of transvestism.

While Hirschfeld was ahead of his time in many of the ways he conceptualized gender difference, he did not distinguish between individuals who cross-dressed but who identified as their birth gender and individuals who identified as a gender different from the one assigned to them at birth and who lived cross-gendered lives, which included cross-dressing. Among the 17 people in his study, four had lived part of their lives as a different gender, including the female-assigned participant, and would now likely be thought of as transsexual or transgender (Meyerowitz, 2002).

Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science, the world’s first institute devoted to sexology, also performed the earliest recorded genital transformation surgeries. The first documented case was that of Dorchen Richter, a male-assigned individual from a poor German family who had desired to be female since early childhood, lived as a woman when she could, and hated her male anatomy. She underwent castration in 1922 and had her penis removed and a vagina constructed in 1931 (Meyerowitz, 2002, p. 19).

The institute’s most well-known patient was Einar Wegener, a Dutch painter who began to present and identify as Lili Elbe in the 1920s. After being evaluated by Hirschfeld, Elbe underwent a series of male-to-female surgeries. In addition to castration and the construction of a vagina, she had ovaries inserted into her abdomen, which at a time before the synthesis of hormones, was the only way that doctors knew to try to change estrogen levels. In 1931, she proceeded with a final operation to create a uterus in an attempt to be a mother, but she died from complications from the surgery (Hoyer, 1953; Kennedy, 2007).

Before her death, Elbe requested that her friend Ernst Ludwig Hathorn Jacobson develop a book based on her diary entries, letters, and dictated material. Jacobson published the resulting work, A Man Changes His Sex, in Dutch and German in 1932 under the pseudonym Niels Hoyer. It was translated into English a year later as Man into Woman: An Authentic Record of a Change of Sex and is the first known book-length account of a gender transition (Meyerowitz, 2002).

Elbe was one of Hirschfeld’s last patients. With the rise of Nazism, the ability for him to do his work became increasingly more difficult, and it became impossible after Adolph Hitler personally called Hirschfeld “the most dangerous Jew in Germany” (Stryker, 2008, p. 40). Fearing for his life, Hirschfeld left the country, and in his absence, the Nazis destroyed the Institute in 1933, holding a public bonfire of its contents. Hirschfeld died in exile in France 2 years later.

Although opportunities for surgical transition diminished with the destruction of Hirschfeld’s Institute, two breakthroughs in hormonal research in the 1930s gave new hope to individuals who felt gender different. First, the discovery by endocrinologists that “male” hormones occurred naturally in women and that “female” hormones occurred naturally in men challenged the dominant scientific thinking that there were two separate and mutually exclusive biological sexes. The findings refuted the medical profession’s assumption that only men could be given “male” hormones and women given “female” hormones, making cross-gender medical treatments possible (H. Rubin, 2006). At the same time, the development of synthetic testosterone and estrogen enabled hormone therapy to become more affordable and, over time, more widely available. In the 1930s and 1940s, few European and US physicians were willing to provide hormones to patients seeking to transition, but a small number of gender nonconforming individuals found ways to obtain them (Kennedy, 2007).

The first female-assigned individual known to have taken testosterone for the purpose of transforming his body was Michael Dillon, a doctor from an aristocratic British family, who had entered medicine in order to better understand his own masculine identity and how he could change his body to be like other men. He began taking hormones in 1939, had a double mastectomy three years later, and underwent more than a dozen operations to construct a penis beginning in 1946. His were the first recorded female-to-male genital surgeries performed on a nonintersex person (Kennedy, 2007; Shapiro, 2010).

The same year that Dillon began his phalloplasty, he also published a book on the treatment of gender nonconforming individuals, Self: A Study in Ethics and Endocrinology. The book focused on the need for society to understand people who, like Dillon, felt that their gender was different from the one assigned to them at birth. Dillon argued that such individuals were not mentally unbalanced but “would develop naturally enough if only [they] belonged to the other sex.” He was especially critical of the psychologists who believed that they could change the sense of self of gender nonconforming individuals through therapy, when what their clients really needed was access to hormones and genital surgeries.

Making an argument that would become commonplace in the years that followed, Dillon reasoned that “where the mind cannot be made to fit the body, the body should be made to fit, approximately, at any rate to the mind, despite the prejudices of those who have not suffered these things” (p. 53). Self, though, was not widely circulated, and Dillon sought to avoid public attention, even taking the extraordinary step of going into exile in India in 1958, when the media discovered his past and ran stories about a transsexual being the heir to a British title.

Instead of Dillon, Harry Benjamin, a German-born, US endocrinologist, became the leading advocate in the 1950s and 1960s for providing hormones and surgeries to gender nonconforming people. Benjamin (1966), like Dillon, saw attempts to “cure” such individuals by psychotherapy as “a useless undertaking” (p. 91), and he began prescribing hormones to them and suggesting surgeons abroad, as no physician in the United States at that time would openly perform gender-affirming operations.

Along with US physician David O. Cauldwell, Benjamin referred to those who desired to change their sex as “transsexuals” in order to distinguish them from “transvestites.” The difference between the groups, according to Benjamin, was that “true transsexuals feel that they belong to the other sex, they want to be and function as members of the opposite sex, not only to appear as such” (1966, p. 13).

In 1949, Cauldwell (2006) was apparently the first medical professional to use the word “transsexual”—which he initially spelled “transexual”—in its contemporary sense. But in sharp contrast to Benjamin, Cauldwell believed that transsexuals were mentally ill and saw gender-affirming surgeries as mutilation and a criminal action. At the time, most physicians supported Cauldwell’s position, assuming that biological sex was the defining aspect of someone’s gender and was immutable, outside of cases of intersex individuals, where the “true” sex of the person may not be immediately known.

Increasingly, though, this belief was challenged by doctors and researchers like Benjamin who distinguished between biological sex and “psychological sex” or, as it came to be known, “gender identity.” As more and more transsexual individuals were acknowledged and studied, these physicians and scientists developed the evidence to begin to gradually shift the dominant medical view to the contrary argument: that gender identity—not biological sex—was the critical, immutable element of someone’s gender. Thus, transsexual individuals needed to be able to change the sex of their bodies to match their sense of self (Meyerowitz, 2002).

Although Harry Benjamin was referring to the issue of transsexuality in general and not to Christine Jorgensen in particular with the title of his pioneering 1966 work The Transsexual Phenomenon, it would not be an exaggeration to characterize her as such. Through the publicity given to her transition, she brought the concept of “sex change” into everyday conversations in the United States, served as a role model for many other transsexual individuals to understand themselves and pursue medical treatment, and transformed the debate about the use of hormones and gender-affirming surgeries. Following the media frenzy over Jorgensen, much of the US public began to recognize that “sex change” was indeed possible.

Born in 1926 to Danish American parents in New York City, Jorgensen struggled with an intense feeling from a young age that she should have been born female. Among the childhood experiences that she recounts in her 1967 autobiography were preferring to play with girls, wishing that she had been sent to a girls’ camp rather than one for boys, and having “a small piece of needlepoint” that she cherished taken away by an unsympathetic elementary school teacher. The teacher confronted Jorgensen’s mother, asking, “Do you think that this is anything for a red-blooded boy to have in his desk as a keepsake?” (p. 18).

Although not mentioned in her autobiography, Jorgensen also apparently began wearing her sister’s clothing in secret when she was young and, by her teens, had acquired her own small wardrobe of “women’s” clothing. Many transsexual individuals dress as the gender with which they identify from a young age, but Jorgensen may have been concerned that readers would confuse her for a “transvestite” or a feminine “homosexual.” She did indicate being attracted to men in her autobiography, and she acknowledged years later to having had “a couple” of same-sex sexual encounters in her youth (Meyerowitz, 2002, p. 57). However, by her early twenties, Jorgensen gradually became aware that she was a heterosexual woman, rather than a cross-dresser or gay man, and began to look for all she could find about medical and surgical transition.

Howard Chiang is assistant professor of history at the University of Warwick and author of Transgender China (2012).

In 1953, 4 years after Mao Zedong’s political regime took over mainland China and the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek was forced to relocate its base, news of the success of native doctors in converting a man into a woman made headlines in Taiwan. On August 14 that year, the United Daily News (Lianhebao) surprised the public by announcing the discovery of an intersex soldier, Xie Jianshun, in Tainan, Taiwan. Within a week, the paper adopted a radically different rhetoric, now with a headline claiming that “Christine Will Not Be America’s Exclusive: Soldier Destined to Become a Lady.” Xie was frequently dubbed the “Chinese Christine.” This allusion to the contemporaneous American ex-G.I. celebrity Christine Jorgensen reflected the growing influence of American culture on the Republic of China at the peak of the Cold War.

Dripping with national and trans-Pacific significance, Xie’s experience made bianxingren (transsexual) a household term in the 1950s. She served as a focal point for numerous new stories that broached the topics of changing sex and human intersexuality. People who wrote about her debated whether she qualified as a woman, whether medical technology could transform sex, and whether the “two Christines” were more similar or different. These questions led to persistent comparisons of Taiwan with the United States, but Xie never presented herself as a duplicate of Jorgensen. As Xie knew, her story highlighted issues that pervaded postwar Taiwanese society: the censorship of public culture by the state, the unique social status of men serving in the armed forces, the limit of individualism, the promise and pitfalls of science, the normative behaviors of men and women, and the boundaries of acceptable sexual expression.

Jorgensen read about the first studies to examine the effects of hormone treatments and about “various conversion experiments in Sweden,” which led her to obtain commercially synthesized female hormones and to travel “first to Denmark, where [she] had relatives, and then to Stockholm, where [she] hoped [she] would find doctors who would be willing to handle [her] case” (pp. 81 and 94). While in Denmark, though, Jorgensen learned that doctors in that country could help her. She came under the care of leading endocrinologist Christian Hamburger, who treated her with increasingly higher doses of female hormones for 2 years, beginning in 1950, and arranged for her to have operations to remove her testicles and penis and to reshape her scrotum into labia.

While recovering from this latter operation in December 1952, Jorgensen went from being an unknown American abroad to “the most talked-about girl in the world.” It seems astounding today to think that someone would become internationally famous simply for altering her appearance through electrolysis, hormones, and surgeries, but that was Jorgensen’s experience when news of her gender transition reached the press (Serlin, 1995, p. 140; Stryker, 2000). A trade magazine for the publishing industry announced in 1954 that Jorgensen’s story over the previous year “had received the largest worldwide coverage in the history of newspaper publishing.” Looking back years later on the media’s obsession, Jorgensen (1967) remained incredulous: “A tragic war was still raging in Korea, George VI died and Britain had a new queen, sophisticated guided missiles were going off in New Mexico, Jonas Salk was working on a vaccine for infantile paralysis....[yet] Christine Jorgensen was on page one” (pp. 249 and 144).

Jorgensen was by no means the first person to undergo a gender transition, and some of these cases had been widely covered in the media. However, Jorgensen became a sensation, in part, because she had been a US serviceman, the epitome of masculinity in post–World War II America (though Jorgensen served in the United States and never saw combat), and had been reborn into a “blonde bombshell,” the symbol of 1950s white feminine sexuality (Meyerowitz, 2002, p. 62).

The initial newspaper story, published in The New York Daily News on December 1, 1952, highlighted this dramatic transformation, with its headline, “Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty,” and its accompanying “before” and “after” photographs. A grainy Army picture of a nerdish-looking, male-bodied Jorgensen in uniform is contrasted with a professionally taken profile picture of a feminine Jorgensen looking like Grace Kelly.

The tremendous attention that Jorgensen’s transition received also reflected the public’s fascination with the power of science in the mid-20th century. A tidal wave of remarkable inventions—from television and the transistor radio to the atomic bomb—had made scientists in the 1950s seem capable of anything, so why not the ability to turn a man into a woman? However, in the aftermath of the first use of nuclear weapons, Jorgensen’s transformation was also pointed to as evidence that science had gone too far in its efforts to alter the natural environment. Jorgensen thus served as a symbol for both scientific progress and a fear that science was attempting to play God. By being at the center of postwar debates over technological advancement, she remained in the spotlight well after the initial reports of her transition and was able to have a successful stage career based on her celebrity status (Meyerowitz, 2002).

Anxieties over changing gender roles were another factor that contributed to Jorgensen’s celebrity. At a time when millions of US women who had been recruited to work in factories during the war were being pushed back into the home in order to make way for returning servicemen, gender expectations for both women and men were in a state of flux. Suddenly, the assumed naturalness of what it meant to be male and female was being called into question. Not only could women do “men’s” work, but men could also become women. As historian Susan Stryker writes, “Jorgensen’s notoriety in the 1950s was undoubtedly fueled by the pervasive unease felt in some quarters that American manhood, already under siege, could quite literally be undone and refashioned into its seeming opposite through the power of modern science” (Stryker, 2000, p. viii).

Dallas Denny and Jamison Green

Gender-variant characters and themes are especially prevalent in science fiction and fantasy. One of the genre’s superstars, Robert A. Heinlein, wrote several pieces that touch on this topic. His short story All You Zombies, written in 1958, is without a doubt the ultimate (and perhaps the only) example of time-travel gender-fuck fiction. The main (actually, only) character in the work is not only at various times male and female, and both the mother and father of their own offspring, but manages to set up the entire conundrum in the first place. Heinlein’s 1970 novel I Will Fear No Evil features an ailing old man whose brain is transplanted into the body of a brain-dead young woman. His novel Friday (1982) resonates with many transgendered people because of its themes of discrimination and passing. Friday is an artificial person, laboratory born, and her social experiences closely reflect those of transsexual women.

Some science-fiction and fantasy authors have portrayed alien races with more or different genders that those on Earth. For example, Ursula LeGuin’s 1969 The Left Hand of Darkness features aliens who are gendered only when reproducing, and who alternately take on male and female roles and characteristics. The aliens in Isaac Asimov’s The Gods Themselves have not two, but three genders.

A number of science fiction authors (LeGuin included) have made feminist statements through the use of gender-variant characters in their speculative fiction. Science fiction critic Cheryl Morgan includes in this feminist category Angela Carter’s The Passion of New Eve (1977). In this novel, a chauvinistic professor of English is surgically transformed into a woman and then experiences rape, enslavement, humiliation, and (almost) forced impregnation.

While many in 1950s America were deeply troubled by what Jorgensen’s transition meant for traditional gender roles, many transsexual individuals, particularly transsexual women, experienced a tremendous sense of relief. They finally understood and had a name for the sense of gender difference that many had felt from early childhood and recognized that others shared their feelings.

“Christine Jorgensen’s return to the U.S. was a true lifesaving event for me....The only thing that kept me from suicide at 12 was the publicity of Christine Jorgensen. It was the first time I found out that there were others like me— I was no longer alone.”

“When her surgery was on the front pages, I was giddy because for the first time ever I realized it was possible.”

Many other transsexual individuals also saw themselves in Jorgensen and hoped to gain access to hormones and surgical procedures. In the months following her return to the United States, Jorgensen received “hundreds of tragic letters...from men and women who also had experienced the deep frustrations of lives lived in sexual twilight.” Her endocrinologist, Dr. Hamburger was likewise inundated with requests from individuals seeking to transition; in the 10 and a half months following his treatment of Jorgensen, he received more than 1, 100 letters from transsexual people, many of whom sought to be his patients (Jorgensen, 1967, pp. 149–150).

Deluged with requests from people around the world who wanted to travel to Denmark for hormonal and surgical treatments in the wake of the media frenzy over Jorgensen, the Danish government banned such procedures for noncitizens. In the United States, many physicians simply dismissed the rapidly growing number of individuals seeking gender-affirming surgeries as being mentally ill. Other, more sympathetic doctors were reluctant to operate because of a fear that they would be either criminally prosecuted under “mayhem” statutes for destroying healthy tissue or sued by patients who were unsatisfied with the surgical outcomes. Thus, despite the tremendous demand, only a few dozen, mostly secretive, genital surgeries were performed in the United States in the years after Jorgensen first made headlines (Stryker, 2008).

Not until the mid-1960s did gender-affirming surgery become more available. The constant mainstream media coverage of transsexual people in the decade following the disclosure of Jorgensen’s transition made it increasingly difficult for the medical establishment to characterize them as a few psychologically disordered individuals. At the same time, the first published studies of the effects of gender-affirming surgery demonstrated the benefits of medical intervention.

Harry Benjamin, who worked with more transsexual individuals than any other physician in the United States, found that among 51 of his trans women patients who underwent surgery, 86% had “good” or “satisfactory” lives afterward. He concluded: “I have become convinced from what I have seen that a miserable, unhappy male [assigned] transsexual can, with the help of surgery and endocrinology, attain a happier future as a woman” (Benjamin, 1966, p. 135; Meyerowitz, 2002). The smaller number of trans men patients he saw likewise felt better about themselves and were more psychologically well-adjusted following surgery.

Within months of the publication of Benjamin’s The Transsexual Phenomenon in 1966, Johns Hopkins University opened the first gender identity clinic in the United States to diagnose and treat transsexual individuals and to conduct research related to transsexuality. Similar programs were soon established at the University of Minnesota, Stanford University, the University of Oregon, and Case Western University, and within 10 years, more than 40 university-affiliated clinics existed throughout the United States (Bullough & Bullough, 1998; Denny, 2006; Stryker, 2008).

The sudden proliferation of health care services for transsexual individuals reflected not only the effect of Benjamin’s work and the influence of a prestigious university like Hopkins on other institutions but also the behind-the-scenes involvement of millionaire philanthropist Reed Erickson. A transsexual man and a patient of Benjamin, Erickson created a foundation that paid for Benjamin’s research and helped fund the Hopkins program and other gender identity clinics. The agency also disseminated information related to transsexuality and served as an indispensable resource for individuals who were coming out as transsexual (Stryker, 2008).

The establishment of gender identity clinics at leading universities called attention to the health care needs of transsexual people and helped to legitimize gender-affirming surgery. However, most clinics provided hormones and surgery only to individuals who fit a very narrow definition of “transsexual”—someone who has felt themselves to be in the “wrong” body from their earliest memories and who is attracted to individuals of the same birth sex as a member of the “other” sex (i.e., a heterosexual trans person). As detailed by trans writer Dallas Denny (2006):

To qualify for treatment, it was important that applicants report that their gender dysphorias manifested at an early age; that they have a history of playing with dolls as a child, if born male, or trucks and guns, if born female; that their sexual attractions were exclusively to the same biological sex; that they have a history of failure at endeavors undertaken while in the original gender role; and that they pass or had potential to pass successfully as a member of the desired sex. (p. 177)

Unable to meet these narrow and biased criteria, the vast majority of interested people were turned away from the gender identity clinics. In its first 2.5 years, Johns Hopkins received almost 2, 000 requests for gender-affirming surgery but performed operations on only 24 individuals (Meyerowitz, 2002).

Jodi Kaufmann is an associate professor at Georgia State University.

Trans people spend a lot of time helping others to understand what it’s like to be trans. There are three primary narratives trans people have turned to in order to share their stories.

The “hermaphroditic narrative” emerged in Germany with the story of Lili Elbe, one of the first transgender people to record her story. Elbe said she was a female “personality” born into a hermaphroditic (or what today would be called intersex) body, a body with both male and female reproductive organs. The hermaphroditic narrative—having a hermaphroditic body and a desire for men—allowed Elbe to receive a sex change operation in the West. Elbe’s autobiography was translated into English in 1933, and her story spread in the United States.

The hermaphroditic narrative began to wane in the years following World War II, and the “sex-gender misalignment” narrative took hold. In 1949, psychiatrist David Cauldwell defined “trans-sexual” people as those who are physically of one sex and psychologically of the opposite sex. Harry Benjamin, an endocrinologist, helped spread this “born in the wrong body” narrative. In order to be diagnosed as transsexual by doctors like Benjamin, one had to use this narrative, and because only those with the diagnosis could access sex reassignment surgery, trans people felt pressure to use it.

The “queer narrative” began in the 1960s, when the assumed norms of binary gender and heterosexuality came under scrutiny. People started telling stories of who they were that did not align with the hetero-norm. The “queer narrative” hit academia when writer Sandy Stone called for posttranssexuality, or the acceptance of a wider range of expressions of sex and gender.

Over time, the ways in which we talk about transsexual identity and experience have changed. Each narrative has had personal and political significance, offering possibilities and limitations; for instance, the “sex-gender misalignment” narrative aided in gaining medical assistance for transitioning but also reinforced hetero-normative ways of thinking about sex and gender. There is no single narrative that fits every trans body and no narrative that remains free from political and personal limitations. It is critical to be aware of how we share and listen to experiences of sex and gender, because the narratives we use can have powerful consequences.

Transsexual men especially encountered difficulties convincing doctors to approve them for surgery. In the wake of the extraordinary publicity given to Jorgensen and the transsexual women who followed her in the spotlight in the 1950s and 1960s, transsexuality became seen as a primarily trans female phenomenon. The medical establishment gave little consideration to transsexual men, and some physicians questioned whether trans men should even be considered transsexuals (Meyerowitz, 2002).

Admittedly, many trans men did not recognize themselves as transsexual either. While they may have known about Jorgensen and other transsexual women, they did not know anyone who had transitioned from female to male or that such a transition was even possible. This sense of being “the only one” was especially common among the transsexual men who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s (Beemyn & Rankin, 2011).

Transsexual men who did transition often did not pursue surgery to construct a penis because the process was expensive, involved multiple surgeries, and produced imperfect results. Moreover, few doctors were skilled in performing phalloplasties. In the United States, the first “bottom surgeries” for trans men were apparently not undertaken until the early 1960s, and even when the gender identity clinics opened, the programs did only a handful of such operations (Meyerowitz, 2002). The vast majority of transsexual men had to be satisfied with hormone therapy and the removal of their breasts and internal reproductive organs, surgeries which were already commonly performed on women. However, since the effects of hormones (especially increased facial hair and lower voices) and “top surgery” enabled trans men to be seen more readily by others as men, these steps were considered more critical by most transsexual men.

In 1952, the year that Jorgensen became an international media phenomenon, a group of cross-dressers in the Los Angeles area led by Virginia Prince quietly created a mimeographed newsletter, Transvestia: The Journal of the American Society for Equity in Dress. Although its distribution was limited to a small number of cross-dressers on the group’s mailing list and it lasted just two issues, Transvestia was apparently the first specifically transgender publication in the United States and served as a trial run for wider organizing among cross-dressers.

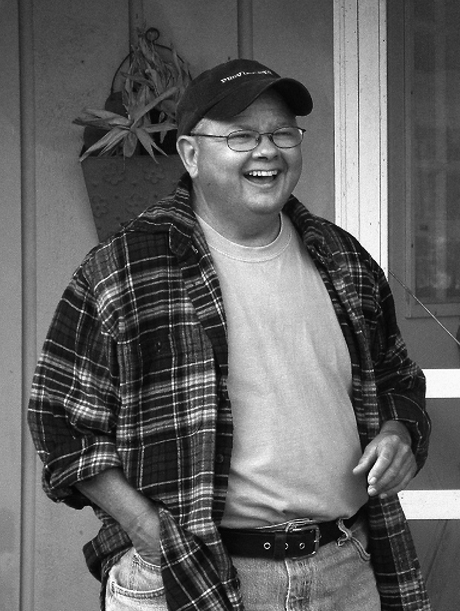

Virginia Prince, pioneer (copyright Mariette Pathy Allen).

Prince relaunched Transvestia in 1960 as a bimonthly magazine with 25 subscribers. Sold through adult bookstores and by word of mouth, Transvestia grew to several hundred subscribers within two years and to more than 1, 000 from across the country by the mid-1960s (Ekins & King, 2005; Prince, 1962; Prince & Bentler, 1972). Prince wrote regular columns for the magazine but relied on readers for much of the content, which included life stories, fiction, letters to the author, personal photographs, and advice on cross-dressing. The involvement of its subscribers, many of whom came out publicly for the first time on the magazine’s pages, had the effect of creating a loyal fan base and contributed to its longevity. Prince’s commitment also sustained Transvestia; she served as its editor and publisher for 20 years, retiring after its hundredth issue in 1979 (Hill, 2007).

Through Transvestia, Prince was able to form a transgender organization that continues more than 50 years later. A year after starting the magazine, she invited several Los Angeles subscribers to a clandestine meeting in a local hotel room. The female-presenting cross-dressers were requested to bring stockings and high heels, but they were not told that the others would be there. When the meeting began, Prince had them don the female apparel, thus outing themselves to each other and forcing them to maintain their shared secret. Initially known as the Hose and Heels Club, the group was renamed the Foundation for Personality Expression (FPE or Phi Pi Epsilon) the following year by Prince, who envisioned it as the alpha chapter of a sorority-like organization that would have chapters throughout the country. By the mid-1960s, several other chapters had been chartered by Prince, who set strict membership requirements.

Only individuals who had subscribed to and read at least five issues of Transvestia could apply to join, and then they had to have their application personally approved by Prince and be interviewed by her or an area representative. Prince kept control over who could be a member through the mid-1970s, when FPE merged with a Southern California cross-dressing group, Mamselle, to become the Society for the Second Self or Tri-Ess, the name by which it is known today (Ekins & King, 2005; Stryker, 2008). Continuing the practice of FPE, Tri-Ess is modeled on the sorority system and currently has more than 25 chapters throughout the country.

Angelika Van Ashley

At about the age of 5, I began to recognize myself as being different somehow from boys. I had no clue as to what was going on inside as a child growing up in the 1950s. I began to do research secretly in the mid-1960s, when I was in my early teens, to try to figure out what was going on, but what I found only said that my condition was an illness and curable. I finally discovered Masters and Johnson’s research, which spoke of “transvestism” in a more humane and positive light. The term still felt clinical, but I saw myself reflected enough in the description to think “maybe that’s what I am.”

My now ex-partner was my support system for many years, and she learned about Tri-Ess on the Internet. There was a chapter, Sigma Rho Delta (SRD), near me in Raleigh, North Carolina. I wasn’t looking for support or understanding, just simple camaraderie, and SRD provided that for me. It was fun.

The group began with a handful of members, but it soon grew exponentially as word got out via the street and the Internet. We went from three to 40 members. I served as vice president of membership and later as president. All persuasions and ages passed through our door. Twenty-somethings to people over 70 years young. Timid, garden-variety cross-dressers in hiding from years of accumulated fear. Bold and boisterous politicos. Fetish practitioners. The white glove and party manner set. Those in transition or considering it. Musical and artistic types. Truck drivers and doctors. Computer geeks and business owners. Individuals with disabilities or who were physically ailing.

We landed in restaurants, clubs, and at theatres. We played music together and laughed a lot at ourselves. We had picnics. Members who were so inclined bravely attended events of a political nature, such as lobby days at the state legislature, where we asked our elected officials their positions on the pending ENDA (Employment Non-Discrimination Act) and LGBT-inclusive hate crimes bill. We even crashed a high-dollar-per-plate Human Rights Campaign fundraiser that featured Representative Barney Frank and confronted him about his stance on transgender inclusion in the aforementioned legislation. We had a sense of strength within our own diversity.

Although membership declined and the group eventually disbanded, our lasting impressions and friendships have carried on past the decade of Sigma Rho Delta’s existence. We still stay in touch and visit one another. We are proud of our unique heritage and the challenges that we met together and as individuals. We found pride in ourselves.

Transvestia and FPE/Tri-Ess reflected Prince’s narrow beliefs about cross-dressing. In her view, the “true transvestite” is “exclusively heterosexual,” “frequently...married and often fathers,” and “values his male organs, enjoys using them and does not desire them removed” (Ekins & King, 2005, p. 9). She not only excluded admittedly gay and bisexual male cross-dressers and transsexual women but also was scornful of them; she openly expressed antigay sentiment and was a leading opponent of gender-affirming surgery. By making sharp distinctions between “real transvestites” and other groups, Prince addressed the two main fears of the wives and female partners of heterosexual male cross-dressers: that their husbands and boyfriends will leave them for men or become women. In addition, she sought to downplay the erotic and sexual aspects of cross-dressing for some people in order to lessen the stigma commonly associated with transvestism and to normalize the one way in which white, middle-class heterosexual male cross-dressers like herself were not privileged in society. In the mid-1960s, Transvestia was promoted as being “dedicated to the needs of the sexually (that’s heterosexual) normal individual” (Ekins & King, 2005, p. 7; Stryker, 2008).

Prince further sought to dissociate transvestism from sexual activity by coining the term “femmiphile”—literally “lover of the feminine”—as a replacement for “transvestite” in the 1960s. “Femmiphile” did not catch on, but the word “cross-dresser” slowly replaced “transvestite” as the preferred term among most transgender people and supporters. As gay and bisexual men who presented as female increasingly referred to themselves as drag queens, “cross-dresser” began to be applied only to heterosexual men—achieving the separation that Prince desired.

Prince deserves a tremendous amount of credit for bringing a segment of formerly isolated cross-dressers together, helping them to recognize that they are not pathological or immoral, creating a national organization that has provided support to tens of thousands of members and their partners over the past 50 years, and increasing the visibility of heterosexual male cross-dressers. At the same time, by preventing gay and bisexual cross-dressers from joining her organizations, she helped ensure that they would identify more with the gay community than with the cross-dressing community and form their own groups; thus, Prince’s prejudice and divisiveness foreclosed the possibility of a broad transgender or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) political coalition developing in the 1960s.

The largest and oldest continuing organization consisting primarily of gay male cross-dressers or drag queens, the Imperial Court System, was founded by José Sarria in San Francisco in 1965. Beginning with other chapters (known as “realms”) in Portland, Oregon, and Los Angeles, the court system has grown today to more than 65 local groups in the United States, Canada, and Mexico; reflecting this expansion, its name is now the International Court System (Imperial Sovereign Rose Court, 2014). The primary mission of each chapter is to raise money for LGBTQ, HIV/AIDS, and other charities through annual costume balls and other fundraising events. Involvement often pays personal dividends as well. According to Steven Schacht (2002), a sociologist who has participated in the group, “courts also serve as an important conduit for gay and lesbian individuals to do drag and as a venue for formal affiliation and personal esteem (largely in the form of various drag titles; i.e. Empress, Emperor, Princess, and Prince) often unavailable to such individuals in the dominant culture” (p. 164).

By the late 1960s, black drag queens were organizing their own events. Growing out of the drag balls held in New York City earlier in the century, these gatherings began in Harlem and initially focused on extravagant feminine drag performances. As word spread about the balls, they attracted larger and larger audiences and the competitions became fiercer and more varied. The drag performers “walked” (competed) for trophies and prizes in a growing number of categories beyond most feminine (known as “femme realness”) or most glamorous, including categories for “butch queens”—gay and sometimes trans men who look “real” as different class-based male archetypes, such as “business executive,” “school boy,” and “thug.”

The many individuals seeking to participate in ball culture led to the establishment of “houses,” groups of Black and Latin@ “children” who gathered around a “house mother” or less often a “house father,” in the mid-1970s. These houses were often named after their leaders, such as Crystal LaBeija’s House of LaBeija, Avis Pendavis’s House of Pendavis, and Dorian Corey’s House of Corey, or took their names from leading fashion designers like the House of Chanel or the House of St. Laurent. The children, consisting of less experienced performers, walked in the balls under their house name and sought to win trophies for the glory of the house and to achieve “legendary” status for themselves. Given that many of the competitors were poor African American and Latin@ youth who came from broken homes or had been thrown out of their homes for being gay or transgender, the houses provided a surrogate family and a space where they could be accepted and have a sense of belonging (Cunningham, 1995; Trebay, 2000).

The ball culture spread to other cities in the 1980s and 1990s and achieved mainstream visibility in 1990 through Jennie Livingston’s documentary Paris Is Burning and Madonna’s mega-hit song and video “Vogue.” In recent years, many of the New York balls have moved out of Harlem. They continue to include local houses and groups from other cities competing in a wide array of categories. Reflecting changes in the wider Black and Latin@ cultures, hip-hop and R & B have become more prominent in the ball scene, and a growing number of performers are butch queens who imitate rap musicians (Cunningham, 1995; Trebay, 2000).

In the 1950s and 1960s, lesbian, gay, and bisexual cross-dressers also found a home in bars, restaurants, and other venues that catered to (or at least tolerated) such a clientele. Sarria, for example, performed in drag at San Francisco’s Black Cat Bar in the 1950s and early 1960s and helped turn it into a social and cultural center for the city’s gay community until harassment from law enforcement and local authorities forced the bar to close (Boyd, 2003). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals—both those who did drag and those who did not—similarly carved out spaces in other US cities, despite regular police crackdowns against them.

Transsexual individuals also began to organize in the 1960s, though most of these efforts were small and short lived. In 1967, transgender people in San Francisco formed Conversion Our Goal, or COG, the first known transsexual support group in the United States. However, within a year, the organization had disintegrated into two competing groups, neither of which existed for very long. More successful was the National Transsexual Counseling Unit, a San Francisco–based social service agency established in 1968 with funding from Reed Erickson. That same year in New York City, Mario Martino, a transsexual man and registered nurse, and his wife founded Labyrinth, a counseling service for trans men. It was the first known organization in the United States to focus on the needs of transsexual men and worked with upwards of 100 transitioning individuals (Martino, 1977; Stryker, 2008).

The 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York City have become legendary as the start of LGBTQ militancy and the birthplace of the LGBTQ liberation movement. However, Stonewall was not a unique event but the culmination of more than a decade of militant opposition by poor and working-class LGBTQ people to discriminatory treatment and police brutality. Much of this resistance took the form of spontaneous, everyday acts of defiance that were never documented or received little attention at the time, even in LGBTQ communities (Stryker, 2008).

The film Screaming Queens: The Riots at Compton’s Cafeteria connects the events at San Francisco’s Compton’s Cafeteria to the historical movements of the 1960s.

For example, one night in May 1959, two Los Angeles police officers went into Cooper’s Donuts—an all-night coffeehouse popular with drag queens and gay male hustlers, many of whom were Latin@ or African American—and began harassing and arresting the patrons in drag. The customers responded by fighting back, first by throwing doughnuts and ultimately by engaging in skirmishes with the officers that led the police to retreat and to call in backup. In the melee, the drag queens who had been arrested were able to escape (Faderman & Timmons, 2006; Stryker, 2008).

Sylvia Rivera and many of the other Stonewall participants were active in the women’s movement, the civil rights movement, and the anti–Vietnam War movement, and recognized that they would have to demand their rights as LGBTQ people, too. Rivera stated: “We had done so much for other movements. It was time....I always believed that we would have [to] fight back. I just knew that we would fight back. I just didn’t know it would be that night” (Feinberg, 1998, pp. 107, 109).

A similar incident occurred in San Francisco in 1966 at the Tenderloin location of Gene Compton’s Cafeteria—a 24-hour restaurant that, like Cooper’s, was frequented by drag queens and male hustlers, as well as the people looking to pick them up. As documented by historian Susan Stryker, the management called the police one August night, as it had done in the past, to get rid of a group of young drag queens who were seen as loitering. When a police officer tried to remove one of the queens forcibly, she threw a cup of coffee in his face and a riot ensued. Patrons pelted the officers with everything at their disposal, wrecking the cafeteria in the process. Vastly outnumbered, the police ran outside to call for reinforcements, only to have the drag queens chase after them, beating the officers with their purses and kicking them with their high heels. The incident served to empower the city’s drag community and motivated many to begin to organize for their rights (Silverman & Stryker, 2005; Stryker, 2008).

Three years later, the much larger and more widely known Stonewall Riots—which started at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City on June 28, 1969, and continued on and off for six days—inspired gender nonconforming people across the country and led to activism on an even greater scale. As with the earlier confrontations in Los Angeles and San Francisco, the immediate impetus for the Stonewall uprising was oppression by the local police, who regularly raided bars that were frequented by LGBTQ people to brutalize and arrest the patrons and to obtain payoffs from the bar owners in order to keep from being shut down. But the riots also reflected long-simmering anger. “Back then we were beat up by the police, by everybody....You get tired of being just pushed around,” recalls Sylvia Rivera, a Puerto Rican transgender woman who was a leader in the riots and the LGBTQ organizing that occurred afterward. “We were not taking any more of this shit” (Carter, 2004; Feinberg, 1998, p. 107).

Felicia Elizondo and Dee Dee at Compton’s Cafeteria riot anniversary, San Francisco, August 20, 2012 (photo by Liz Highleyman).

Sylvia Rivera, homeless, with Marlboro Man (copyright Mariette Pathy Allen).

On that June night, the police raided the Stonewall Inn and as usual began arresting the bar’s workers, customers who did not have identification, and those who were cross-dressed. But unlike in the past, the other patrons did not scatter when they were allowed to leave. Instead, they congregated outside and, with other LGBTQ people from the neighborhood, taunted the police as they tried to place the arrestees into a patrol wagon.

Accounts from this point on differ as to what incited the onlookers to violence; it is likely that events happened so fast that there was not one single precipitating incident. As the crowd grew, so too did anger toward the police for their rough treatment of the drag queens and at least one butch lesbian whom they had arrested. People began to throw coins at the officers, and when this failed to halt the brutality or to alleviate years of pent-up anger, they hurled whatever they could find—cans, bottles, cobblestones, and bricks from a nearby construction site (Duberman, 1993).

Unaccustomed to LGBTQ people resisting police brutality and fearful for their safety, the eight police officers retreated and barricaded themselves into the bar. In a reversal of roles, the LGBTQ crowd then tried to break in after them, while at least one person attempted to set the bar on fire. The arrival of police reinforcements likely kept those inside the bar from firing on the protesters. However, even the additional officers, who were members of an elite riot-control unit, could not immediately quell the uprising. The police would scatter people by wading into the crowd swinging their billy clubs, but rather than flee the area, the demonstrators simply ran around the block and, regrouping behind the riot squad, continued to jeer and throw objects at them.

At one point, the police turned around to a situation for which their training undoubtedly did not prepare them: a chorus line of drag queens, calling themselves the “Stonewall girls,” kicked up their heels—à la the Rockettes—and sang mockingly at the officers. Eventually, the police succeeded in dispersing the crowd, but only for the night. The rioting was similarly violent the following evening—some witnesses say more so—and sporadic and less combative demonstrations continued for the next several days (Duberman, 1993).

The effects of the Stonewall Riots were immediate and far-reaching. Among the first to notice a change in the LGBTQ community was Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, the police officer who led the raid on the bar that night. “For those of us in public morals, things were completely changed,” Pine stated after the rebellion. “Suddenly [LGBTQ people] were not submissive anymore” (Duberman, 1993, p. 203).

The biggest impact may have been on LGBTQ youth. At the time of the Stonewall Riots, gay rights groups—often chapters of the Student Homophile League—existed at just six colleges in the United States, almost all of which were large universities in the Northeast. By 1971, groups had been formed at hundreds of colleges and universities throughout the country (Beemyn, 2003). Reflecting the sense of militancy that had fueled the uprising, many of the new groups referred to themselves as Gay Liberation Fronts, after the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) that was formed in New York City a month after the riots, and typically had a more radical political agenda than the earlier student organizations. Many of the GLFs were also initially more welcoming to cross-dressers, drag queens, and transsexuals than the pre-Stonewall groups, and a number of transgender people helped form Gay Liberation Fronts.

Transgender people also established their own organizations in the immediate aftermath of the Stonewall Riots. Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, an African American trans woman who had likewise been involved in the riots, founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in New York City in 1970 to support and to fight for the rights of the many young trans people who were living on the city’s streets. Rivera and Johnson hustled to open STAR House, a place where the youth could receive shelter, clothing, and food for free. The house remained open for two or three years and inspired similar efforts in Chicago, California, and England. Also in New York City in 1970, Lee Brewster and Bunny Eisenhower founded the Queens Liberation Front and led a campaign that decriminalized cross-dressing in New York. Brewster began Drag, one of the first politically oriented trans publications, in 1970 (Feinberg, 1998; Zagria, 2009). During this same time, trans man Jude Patton, along with Sister Mary Elizabeth Clark (formerly known as Joanna Clark), used funding from Reed Erickson to start disseminating information to trans people (Moonhawk River Stone, personal communication, May 12, 2013; Jamison Green, personal communication, June 6, 2013).

Despite the central role that trans people played in the Stonewall Riots and the political organizing that followed, much of the broader lesbian and gay movement soon abandoned them in an attempt to be more acceptable to the dominant society. Six months after the Stonewall riots, a group comprised mostly of white middle-class gay men, who were dissatisfied with the multiple issue politics and antiestablishment ethos of GLF, formed the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) in New York City to work “completely and solely” for their own equal rights (Duberman, 1993, p. 232). The group did not consider the rights of trans people to be relevant to its mission; GAA would not provide a loan to pay the rent to keep STAR House open or support a dance to raise the funds. Transgender people also did not feel welcomed in the group. Johnson remembered that she and Rivera were stared at when they attended GAA meetings, being the only trans people and sometimes the only people of color there (Jay & Young, 1972). Similar gay groups that excluded trans people subsequently formed in other cities.

Transgender women also often faced rejection in the 1970s from members of lesbian organizations, who viewed them not as “real women” but as “male infiltrators.” One of the most well-known victims of such prejudice was Beth Elliott, a transsexual lesbian activist and singer who joined the San Francisco chapter of the groundbreaking lesbian group the Daughters of Bilitis in 1971 and became its vice president and the editor of its newsletter. Although Elliott had been accepted for membership, she was forced out the following year as part of a campaign against her. She also faced opposition to her involvement in the 1973 West Coast Lesbian Feminist Conference. Elliott was on the conference’s planning committee and a scheduled performer, but when she took the stage, some audience members attempted to shout her down, saying that she was a man. Others defended her. Elliott managed to get through her performance, but the controversy continued.

In a keynote speech, feminist Robin Morgan viciously attacked Elliott, whom she called a “male transvestite,” who was “leeching off women who have spent entire lives as women in women’s bodies.” Morgan concluded her diatribe by declaring: “I charge him as an opportunist, an infiltrator, and a destroyer—with the mentality of a rapist” (Gallo, 2006; Stryker, 2008, pp. 104–105). Morgan called on the conference attendees to vote to eject Elliott. Although more than two-thirds reportedly chose to allow her to remain, Elliot was emotionally traumatized by the experience and decided to leave anyway.

The campaign against Elliott marked the start of the policing of “women’s spaces” by some lesbian separatists to exclude transsexual women. Another target was Sandy Stone, a sound engineer who, as part of the all-women Olivia Records, helped create the genre of women’s music in the mid-1970s. Stone had disclosed her transsexuality to the other women in the record collective and had their support, but when her gender history became widely known, Olivia was deluged with hate mail from lesbians—some threatening violence, others threatening a boycott if Stone was not fired. The collective initially defended her, but fearing that they would be put out of business, they reluctantly asked Stone to resign, which she did in 1979 (Califia, 1997; Devor & Matte, 2006).

Many lesbians had left activist organizations like GLF and GAA in the early and mid-1970s because of sexism among the predominantly gay male members, and there was not much that united the two groups, but one area of agreement was their rejection of trans people. In 1973, lesbian separatists and more conservative gay men in San Francisco organized an alternative Pride parade that banned trans people and individuals in drag; in subsequent years, this event became the city’s main Pride celebration. At the New York City Pride rally in 1973, Jean O’Leary of Lesbian Feminist Liberation read a statement that denounced drag queens as an insult to women, which further marked the exclusion of trans people from the “lesbian and gay” rights movement (Clendinen & Nagourney, 1999; Stryker, 2008).

The most vitriolic and influential attack on trans people was Janice Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male, published in 1979 and reissued in 1994. Raymond, a scholar in women’s studies, was one of the leading voices against Sandy Stone and against all transsexual women in lesbian feminist communities. While Robin Morgan argued that Elliott had “the mentality of a rapist,” Raymond went further, stating that transsexual women are rapists. In one of the most infamous passages, she claims: “All transsexuals rape women’s bodies by reducing the real female form to an artifact, appropriating this body for themselves.” She also contends that their supposedly secretive presence in lesbian feminist spaces constitutes an act of forced penetration that “violates women’s sexuality and spirit” (p. 104).

For Raymond, transsexual women are not women but “castrated” and “deviant” men who were a creation of the medical and psychological specialties that arose in support of gender-affirming surgeries—“the transsexual empire” to which her title refers. Ignoring centuries of gender nonconformity in cultures around the world, she considers transsexuality to be a recent phenomenon stemming from the development of genital surgeries, which she erroneously traces to Nazi Germany (as stated earlier, the first known gender-affirming surgery was performed in Germany in 1931, two years before Hitler came to power). To resist being taken over by the evil “transsexual empire,” Raymond advocates for a drastic reduction in the availability of gender-affirming surgery and recommends that transsexual individuals instead undergo “gender reorientation” (Stryker, 2008, p. 110).

Raymond’s inflammatory rhetoric and false allegations could be readily dismissed if her arguments had not had such a significant effect. Influenced in part by Raymond’s antitranssexual attacks, the gender identity clinics—which already served only a small number of trans individuals and were largely opposed by the medical establishment—performed even fewer surgeries and began to shut down altogether, starting with the Johns Hopkins program in 1979.

Talia Bettcher is a philosophy professor at Cal State Los Angeles.

It may seem obvious that feminist and trans politics go together like peanut butter and jelly. In both feminist and trans politics, there is a concern with gender oppression, so there appears to be a common cause. Trans women not only experience transphobia but also sexism; many trans men have had firsthand experience with sexism prior to transition (and even after if they are transphobically viewed as “really women”). So it might be surprising to learn that some (non-trans) feminists have viewed trans people in hostile, transphobic ways.

In the 1970s and 1980s, influential “second-wave” (non-trans) feminists such as Robin Morgan, Mary Daly, and Janice Raymond represented trans women as rapists and boundary violators trying to invade women’s space. Trans men were disregarded as mere tokens used to hide the patriarchal nature of the phenomenon of transsexuality. Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male systemizes these hostile views, and in trans circles it is widely regarded as a “classic” of transphobic literature.

While there are still non-trans feminists with these types of views, they are now in the minority. Much of this has to do with the emergence of so-called third-wave feminism. Transgender people are now often thought of as “beyond the binary.” One of the most important consequences of this development is that it became possible to view trans people as oppressed in a way that was not reduced to sexism. Perhaps the most important strand of third-wave feminism is the view that one cannot focus on only one kind of oppression (sexism) to the exclusion of others, such as racism (see Combahee River Collective, 1981). One important lesson of trans feminist Emi Koyama’s work is that any form of trans/feminism which marginalizes other forms of oppression, such as racism, does so at its own peril.