Tarot can become what I call “a complete practice” when we forge for ourselves a sense of the pack as an integrated and self-consistent whole. For the cards to have a voice, for them to engage with us in a practice of mindful inquiry, they need to form the 78 parts of a coherent language. Memorizing individual card meanings, or considering each card in isolation from the others, might give us a Tarot “phrase book,” but knowing how to ask ¿Dónde está el baño? is not the same as having a conversation. In short, we must learn how to speak Tarot. The good news is that Tarot is a language that we ourselves help create.

With the card meanings that follow, I invite you to join in this language creation. Sense your way into the patterns and themes that loop through the trumps, or through each of the four suits. Whatever deck you work with, note the consistencies and parallels, the contradictions and contrasts that help define its structure. Note the life circumstances, the context, in which the cards appear when you pull them for yourself or others. Note the way that one card comments on or reflects another, like lines that rhyme in a poem.51 For instance, in my Mindful Tarot PULL of the last chapter, the wings of the angel in the Lovers card echoed the wings of the hooded falcon in the Nine of Pentacles. The miserly tightness of the Four of Pentacles echoed the squared-off stability of the Emperor. These card “rhymes” will forever help shape and enrich my understanding of all four cards.

Whatever deck you choose, I hereby authorize you, dear reader, to sense your way into its wholeness and integrity. Read the guidebook that came with the deck, but don’t rely on it like a decoder ring. Read the meanings I provide here, but don’t rely on these either. Make your deck yours. Flip through it often, idly or intently. Shuffle it just to feel the cards moving through your hands, to get its textures into your muscle memory. Use your intuition about imagery, number, the natural elements, the nature of the human heart, and so forth. Make the deck’s patterns and structures speak to you.

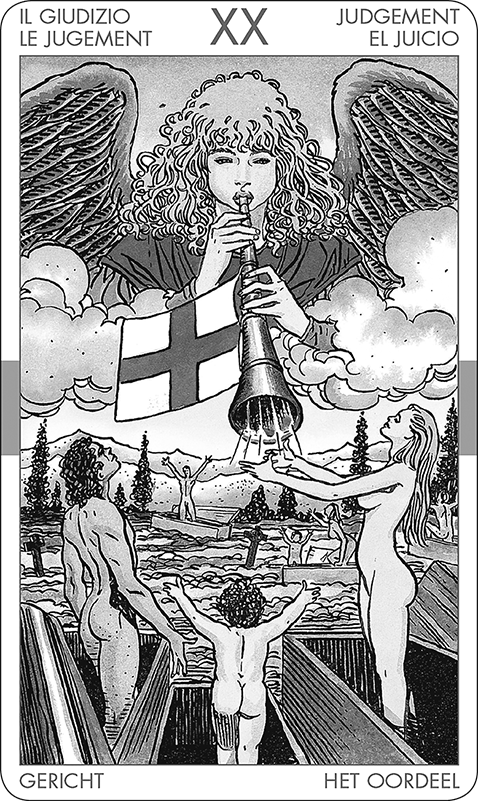

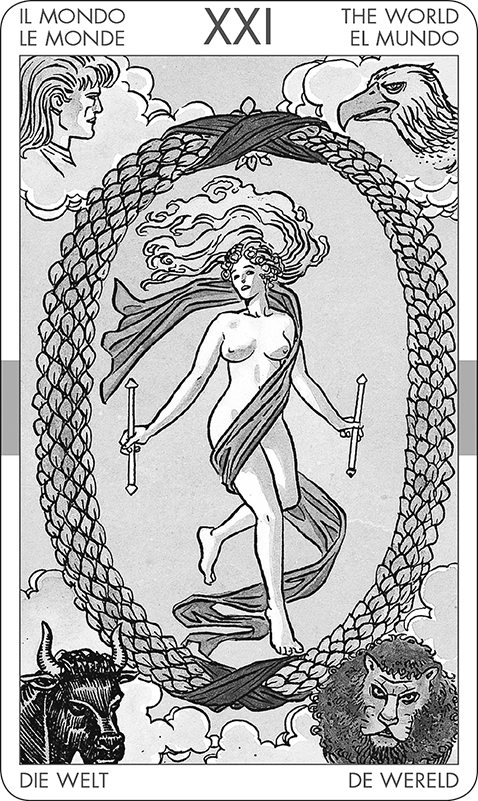

The meanings I offer here are illustrated with Italian artist Roberto de Angelis’s depictions for the Universal Tarot (Lo Scarabeo, 2015). De Angelis’s images adhere very closely to the 1909 Waite-Smith symbolism, and my discussions often refer directly to Arthur Edward Waite’s descriptions in The Pictorial Key to the Tarot or to Pamela Colman Smith’s illustrations for the cards.

But gravitate toward any Tarot deck you like—even if its artwork or schema departs dramatically from the Waite-Smith imagery. As you practice with your own deck, use my discussions that follow to begin your own inquiry—allowing the cards you draw to provoke questions instead of provide answers. Over time you undoubtedly will weave your own sense of the integrity and wholeness of the Tarot into your life.

Over the past five centuries, the symbolism of the Tarot has been reinterpreted and transformed by countless game players, artists, and seekers. In dialogue with tradition, each Tarot practitioner needs to find their own way with the cards. That’s what keeps the Tarot vibrant and alive. That’s what makes it possible for each of us to find our wholeness and integration through a Tarot-based practice. As an interpretive community and a community of practice, we build the language of Tarot together. And together we each learn how to speak that language fluently.

A Word about Dualism

The trumps present stark dichotomies: delineations of presence and absence, right and wrong, gain and loss, active and passive, male and female, black and white. In a dualistic worldview where body and mind are separate, the trumps can seem to invite us on a one-way journey from a messy human life of error, time, waste, and death to some eternal spiritual perfection that lies outside of time and error. A Mindful Tarot approach encourages us instead to dive right into the slop and muck of a fully embodied life. Instead of seeking our freedom outside of time, can we meet the infinite possibilities inherent in each moment? Our work with the trumps will be to bring the beginner’s mind of the Fool to each and every card—to see the opening and the freshness available at each turning point in our lives.

Beginner’s Mind

Can we find a new beginning in each and every moment? A beginning that doesn’t turn toward something else, but just turns toward what’s actually here—right now?

The Ise Jingu grand shrine in the Mie Prefecture, Japan, one of the holiest of all Japanese Shinto temples, has for centuries now been torn down and rebuilt every twenty years. The wooden structure is close to 2,000 years old—and it’s also practically brand-new. Our own bodies are also constantly regenerating themselves, cells breaking down and being rebuilt. The lining of our stomach is renewed every couple of days, the cells of our bones are renewed once a decade, and our skin cells die off and are totally replaced every couple of weeks. The fact is that everything around us and inside us changes endlessly. We live a life of continuous degradation and repair. But somehow our world nonetheless has the quality of continuity and stability. At times of cataclysm, death, disaster, or illness—or, on the happy side of things, times of birth, marriage, and college graduation—we know that things really do change, and that they sometimes change irrevocably. But have you ever experienced a completely life-altering event and found that after the dust settled, things were pretty much as they had been—that in a very important way, you were the same person, for better or worse?

We’re all rubber bands to a certain extent. No matter how much we are stretched out, we pretty much bounce back to our original shape. And by “we,” I include here the grasses and the bees and the rocks and the houses. Despite the fact that everything keeps changing, the world pretty much stays as it is, giving us the illusion that things are solid and permanent.

On one level, that’s good news and the source of our resilience. It’s a good thing that we bounce back like rubber bands. But it’s also not such great news because it means that we’re often trapped within patterns, caught in a rut, and living in a delusion where we think that the shape of things as they’ve always seemed to be is the shape of things as they are. How do we instead find a new beginning? How do we find freshness in this moment?

There’s a deep resonance between the Fool and the aces in the four suits. Those cards are about beginnings, possibilities, and recognizing the present moment for what it is: a present—a gift, an offering that is continually and ceaselessly renewed, as long as we’re alive and kicking. (It’s the gift that keeps on giving!)

When the Fool appears in a reading, we’re being specifically invited to lean into the present of this present moment. To meet this moment in all its mystery and all our not-knowing what it really holds or entails: that is the invitation of the Fool. She stands on what has up until now seemed to be completely solid ground. The void lies open at her feet. Her chin tilts toward the vast and luminous blue sky.

Alignment

How can we channel all the elements of our life, as they appear in this very moment? How might we align everything we know, feel, and witness into one vibrant sense of life?

In the earliest historical decks, this card depicted a trickster and sleight-of-hand artist—the Renaissance equivalent of the guy by the subway station with his makeshift cardboard table and his game of three-card monte. There’s a side of each of us, I think, that wants to imagine that we’re the ones who can beat the system. I remember as a teenager losing all my hard-won babysitting money at a county fair ring toss. I knew that the setup had to be rigged, but I kept imagining somehow that it would be worth it and that I would be the special one to break through. The Juggler or Bateleur, as this card is known in early modern decks, points to the illusory nature of life on earth—and to our tendency to buy into that illusion, not just out of ignorance but often out of greed and arrogance as well.

The modern interpretation of this card may seem wildly different, but it really articulates the same idea from another angle.

For most modern readers, the Magician is the card of creation and manifestation. The Waite-Smith imagery illustrates this idea by evoking the hermetic motto “As above, so below”—a statement that can always be read in two directions. On the one hand, divine truth permeates our world, flowing from the heavens to the earth, just like the radiance of the sun. On the other hand, it’s our job to illuminate the world in response, manifesting the ideal in the midst of brute matter. With arms extended above and below, the Magician’s body echoes the singular uprightness of the Roman numeral for one—the I that marks this card as the first numbered trump.52 The Magician becomes a divine lightning rod, conducting spirit into matter and penetrating the darkness with sacred light. This is a card that denotes our capacity to affect reality and to actualize the truth.

Whether juggler or magician, this first trump invites us to reach for, and align with, what truly matters—instead of being taken in by illusion or misdirected by our own greed and self-importance. It’s also a card that historically relies on a fundamental dualistic understanding of the world: a stark divide between reality and illusion, between heaven and earth, between spirit and matter. This division has uncomfortable consequences. It tends to denigrate the life of the here and now, and to set up self against other. The trump’s numbered marking, that Roman numeral I, bespeaks both unity and will: both the number one and the English first-person pronoun. This I can so easily become the sign of a lethal egoism that sets our will against the world.

But if we sincerely follow the Magician’s lead, this card calls us into alignment. It invites a divine and earnest focus. Whether con man or magus, this card invites us to disregard all fluff and nonsense. Instead, the Magician asks that we attune ourselves to the authentic truth being realized, even now, in every corner of our world.

What do we know to be authentic and real? How do we know it? And how might we align ourselves with its power?

Unknowing

Can we entrust ourselves completely to this life? How do we let every atom of our being function as truth, with nothing hidden and nothing separate?

Recall that the Magician aligns with the known world—the world in all the elements that can be grasped and understood. He works in the realm of the visible—or at least the comprehensible—with what can be known and experienced, through our bodies, hearts, or minds. Laid out before him are the four tools of this work: the pentacle, wand, cup, and sword that represent not only the Tarot itself but also the four material elements (earth, fire, water and air) and the aspects of human agency that correspond with those four elements: body, will, soul, and mind.

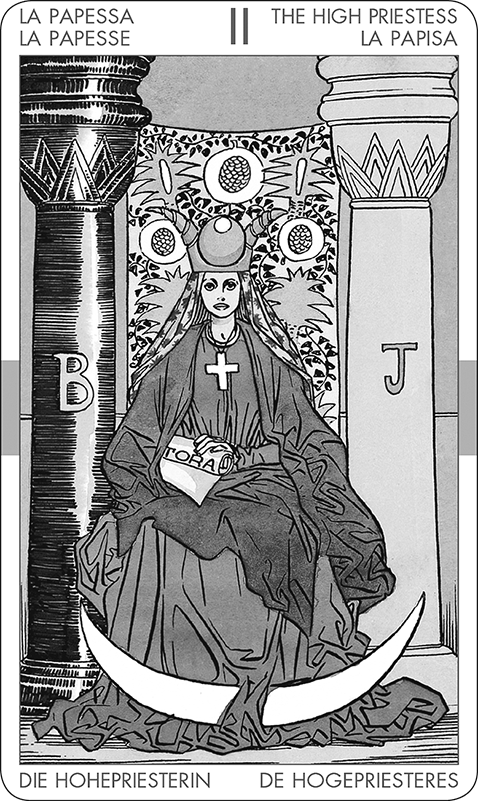

In contrast with the Magician, the High Priestess aligns with the realm of what cannot be known. Her world is one of mysterious and imperceptible depths, traditionally associated with the feminine, with darkness, intuition, water, multiplicity (as opposed to the phallic unity of the Magician), and with the reflected light of the moon. We’ll see all of these features again in Trump XVIII, The Moon. The traditional imagery also suggests that these mysteries can ultimately be plumbed and known.

Behind the High Priestess stretches a vast ocean, mostly hidden by the thin veil at her back: the tapestry embroidered with pomegranates behind her throne. The implication is that we can pass through the veil. We can enter through the yoni-like pomegranates and penetrate the watery depths. In that archetypal association of male as active and grasping and female as receptive, the implication is that we can turn the mysteries of the High Priestess into one more known element within the grasp of the Magician.

However, her mysteries are complete ones. They are fully and radically unknowable. They are uncountable, ungraspable, and unattainable, and ultimately resist becoming another tool on the table of the Magician. The High Priestess knows nothing. Rather, she entrusts herself to a world that is shadow not because it has yet to be enlightened but because it is the backdrop against which everything that can be known is known.

I mean this in a very literal way. As I look out across the terrace this morning, I see a gorgeous field of red poppies. The color red, the name poppy, the concept of a field, the ideas of “terrace” and of “what lies beyond terrace,” the judgments and ideas and emotional valences that make up my sense of what is “gorgeous”: these are all things that I know. And I know these things not just through my five senses but also through my felt experience of happiness (“this is gorgeous!”), through my grasp of a world of ideas, of language, of basic intuitions like spatial and temporal relationships. And on and on. A whole variegated universe of categories makes it possible for me to see and to know this gorgeous field of poppies. That universe of categories is the world in which the Magician hones his skills.

At the same time, there’s everything else. Again and again, in every moment of our lives, we carve out our experiences like sculptures from an infinite field of marble. We grasp flecks of human awareness from the unending stream of existence. And in so doing we light up a piece of that unending stream. But the waters flow on and on and on. The realm of the High Priestess is the realm of everything that isn’t carved out; the shadow against which the known world appears.

There’s a wonderful story I’ve heard, attributed to various sources. It goes something like this. A seeker begins to meditate, experiencing the ways in which her mind is like a vast ocean. She first becomes aware of all the astonishing and sometimes frightening “fish” in that ocean—that is, the various thoughts and feelings that pass through her mind. Great spiny-backed fish, huge predators with gleaming rows of teeth, round-bellied ones with brilliant colors and gemlike fins, squat and sandy-colored bottom feeders, graceful minnows swimming in vast schools. She’s mesmerized by these various sea dwellers at first. But as she meditates over the course of weeks, then months, then years, the fish become less of a distraction. Ah, this fish, that fish: she peacefully takes note as they appear and disappear. As even more time passes, even this note-taking activity slows down and finally stops. And then, one day, she finds herself asking, Hey, what’s this water thing all about??

The High Priestess invites us to entrust ourselves to these deep waters. She invites us into the deepest mystery of life—into life as it’s all around us and all-pervading at every moment. Her mysteries are unknowable not because they are remote but because it is quite literally impossible to know everything. More than anything else, the High Priestess invites us to trust.

Unfolding

What does it mean to surrender to the unfolding of life? For many readers the Empress calls forth the deeply sensuous realm of nature, of creation and creativity. For many, the card embodies the archetype of the mother, and the Empress is sometimes depicted pregnant. Traditionally, the card reminds us that the world itself is our safe, sheltering haven—and also our womb. The world over which the Empress rules is the matrix that nurtures our lives, feeds our dreams, and brings our intentions to fruition.

Artist and Tarot creator Julia Turk offers the keyword conception for this card. “The Empress represents the basic ebb and flow of pulsating nature. There is a deep desire within you to return to nature,” she writes.53

What is this desire to return to nature? I feel it intensely now, sipping my tea on the terrace, surrounded by wild flowers, heavy black bees, and the sweet, high chattering of birds. After the dark mysteries of the High Priestess, and the brilliance of the Magician who seeks to grasp and align all that can be known, the Empress invites us to look down at our feet. Every step of the way, in this life we lead, we find evidence of a universe that pulsates in complex and intertwined rhythms. We are a part of all of that. All around us, at every moment, what is even now unfolding is a beautiful, fruiting, gorgeous life. The basic ebb and flow of pulsating nature. Indeed! What if we allowed ourselves to surrender to this ebb and flow? Can we walk, as the Fool might walk, out into the unknown—with confidence that the path is already unfolding beneath our feet? Can we surrender to life?

It might take every ounce of our energy to do so. Julia Turk writes, “You may have gone through many different experiences recently that have left you confused, as trailing vines obscure the forest path and leave you directionless.” 54 That’s the thing about surrendering to life. Life is rich and abundant and full. Indeed, life is full of entanglements and trailing vines. But it’s important to resist our tendency toward dualism and dichotomy. What makes us think the path is anything other than the trailing vine? At the moment that we encounter confusion and entanglement, we can feel like we’ve taken a wrong turn and lost our way. But the Empress reminds us that all of this is still the endlessly fruitful generosity of life. Every impasse is truly a gate. Every vine is also the path.

I once received a simple meditation instruction as a way to find my breath and settle into the pulsating ebb and flow of mindfulness practice. The teacher told me to hold my breath for as long as I could. “At a certain moment,” he said, “the impulse to breathe will be born in you. Notice that moment, where emptiness turns into fullness. That’s the moment when our life is elicited by the world—and when the world gives us back our life.”

The Empress invites us to set our feet down, and to take one step forward, and then another, and another. Breath by breath, step by step, the path will unfold before us.

Structure

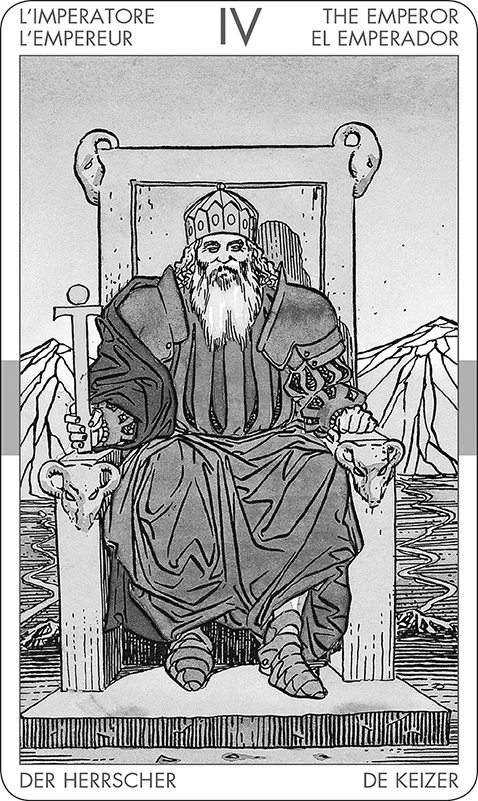

Can we leave the world a more beautiful, meaningful, helpful place than we found it? After the vibrant and alive space of the Empress, with her pulsating, beautifully integrated cycles of life and creativity, what do we do with the control, solidity, and rigidity of the Emperor? Behind the Emperor’s dais we see an arid and dry landscape. The verdant hills and flowing rivers of the Empress’s realm are gone. Instead of her rounded and contoured throne, the Emperor sits on a massive squared seat. On older woodblock decks (such as the Marseille Tarot), this card is numbered with a variant of the Roman numeral four: IIII. The numeral’s four upright pillars offer a visual echo of the Emperor’s throne, with its four upright corners embellished with four ram’s heads.

Indeed, throughout the Tarot we’ll be reminded again and again that there’s something solid and anchored about the number four. Four is the number of structure and building—the number of walls that make a room and of posts that make a platform. There’s also something distinctly human about the number four, evoking our desire to shape and homestead our environment, to turn the natural world into a human dwelling. The Emperor, and the “fourness” he embodies, acts as the creative force with which we meet the richness and abundance of life. And yet, that force brings us to industrial farming and fracking, clear-cut forests and strip-mined valleys. The strength and stability of the Emperor can easily become oppressive.

How did it become remarkable that our food might be “natural,” might be “organic”? Every day as I reach into my refrigerator, I see a joke magnet that someone once gave us: Try Organic Food, the magnet says. Or, as your grandparents called it, Food. In these times of soybean subsidies, demagoguery, tech overload, climate disruption, and a thousand other manmade disasters, the ingenuity of the Emperor can seem like the asphalt that paves paradise and puts up a parking lot.

The stability associated with the number four, and with the Emperor, is the stability of structure per se. It’s a stability born out of a world of twos. As we’ve been seeing, the Tarot thinks in dualities: heaven/earth, male/female, mind/body, active/passive, light/dark, unity/multiplicity, knowledge/mystery. This dualism is never just neutral, of course. There’s always one side of the equation that finds privilege—that our culture identifies as more worthy, or more normal, or more acceptable.

Yet, it’s not just Tarot that thinks in dualisms. This is how we think. Dualisms R Us: this is how the human mind makes sense of the world. We divide this from that, here from there, now from then, me from you. Babies learn how to be good dichotomizers as soon as their babble starts to be recognized as words. Mama! Dada! From our basic ability to divide an undifferentiated world into this and that, we devise languages, skyscrapers, democracies, prison systems, chocolate chip cookies, oil paintings, railroads, flower beds, beehive hairdos, tattoos, and iPhones. The whole kit and caboodle of civilization, for good and bad (another important binary), emerges from our dualistic frame of mind.

And, the Emperor is Mr. Dualism.

The Emperor invites us to take stock of our life, noting the juice and creative energy that’s already abounding and in play. Nothing is ever either/or, and yet now may be a moment for choices, options, clear guidelines, and careful pathways. This card challenges us to stay in the vibrant and verdant garden of the Empress while also cultivating the stability that defines a human life well lived.

Holding Truth

What do we hold as truth, and how does the truth hold us? The Hierophant stands for tradition, like the Emperor stands for structure, and like the Emperor, this card is a challenge for many modern readers.

Its imagery is orthodox, patriarchal, and authoritative. This is the Pope, whose absolute authority is symbolized by the kneeling prelates and the crossed keys of Peter. 55 And, once again we see the Tarot’s tendency to think in dualistic pairs. The Emperor and the Empress present the rule of the earth, from nature to human civilization. In contrast, the High Priestess and the Hierophant (or the Papess and the Pope, as they were originally called) present the rule of the heavens. And just as we saw the Emperor wielding a potentially oppressive and rigid discipline in contrast to the fluid vibrancy of the Empress, so too does the Hierophant traditionally represent the rigidity of orthodox spirituality in contrast to the fluidity of the dark and sacred mystery.

But for all his rule and rigor, our Hierophant is barefoot! Roberto de Angelis’s depiction of this card for the Universal Tarot departs in this one fascinating detail from the traditional Waite-Smith imagery. Pamela Colman Smith’s supreme pontiff wears dainty white shoes adorned with little crosses. Our Hierophant here has hammertoes! There are so many moments in reading Tarot like this one—where one’s personal resonance with a particular card in a specific deck can change everything. These bare feet peeping out from under the formal vestments speak to humility, groundedness, an ancient and holy connection to the earth and the past, and a certain vulnerability.

And to me, quite particularly, the bare feet under the robes also speak to the many hours I’ve sat cross-legged on my cushion in my Zen temple’s meditation hall, where our custom follows the Japanese model and our shoes are always left outside the door. And so I’ve sat in that quiet hall, with downcast eyes, noticing the shuffling of bare feet, noticing my own Zen teacher’s feet, gnarly and calloused and speaking of a life led in walking the path of practice, a life led in contact with the rich, deep earth of Oregon, our home.

In one of the ceremonies at our Zen temple, my barefoot teacher speaks a phrase that always slays me: “I in the ninety-fifth generation now pass this wisdom to you.” My teacher had a teacher, and his teacher had a teacher, and so forth and so on, all the way back to Siddhartha Gautama—to the historical Buddha who awakened to the truth of this precious life some 2,500 years ago. On a daily basis the trainees at our temple recite the names of all of those teachers, going back ninety-five generations, back to the Buddha himself. Ninety-five people is not a lot of people. There were more folks at my wedding than that! Ninety-five is peanuts. I’ve fed almost twice that number of people in a big white tent under the apple tree in my backyard.

It is astonishing to me that I can trace the lineage of the dharma back so visibly, so concretely, across the flow of time.

In literal terms, tradition just means handing something down or over. As a figure of tradition, we can keep the Hierophant in his darkest guise, as the massive patriarch of orthodoxy and spiritual dominion. Or we can imagine all the hands across time who have made the truths of faith apparent. Hand over hand, hand in hand, across time. Tradition is just about hand-me-downs, from one elder sibling to the next—like that dress with the embroidered strawberries that my older sister gave me and that I wore every day I could in second grade, with shorts underneath so I could hang upside down from the monkey bars. Tradition is sometimes nothing more complicated than that.

There’s a humility, maybe even a barefoot humility, in recognizing that no person alone holds the truth. St. Augustine, who was himself a bishop with authority not unlike our Hierophant, once wrote that “God’s truth is neither mine nor his nor another’s, but all of ours. Thus we must commune in God’s truth. Otherwise, by desiring to possess the truth in private we may find ourselves deprived of it.” 56 Augustine goes on to say that lies are indeed the only things that are private. Any speck of truth we might hold belongs to everyone. Truth is communal property.

The Hierophant can feel rigid, static, and unyielding, but we can also understand his tradition as movement: as the common wind of truth that moves with us, moves through us, that supports us and holds us aloft. The Hierophant invites us to ask what matters most in our lives. How did it come to us? And how are we, ourselves, holding it safe—and passing it on?

Becoming Whole

How do we choose our path in the world? Or does the path choose us? A central angelic figure, arms held wide, presides over the most iconic moment of choice in the Western tradition: Adam’s decision to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, choosing the flesh of his flesh, Eve, over the word of God. In the iconic Western view, this is the moment when Man chooses death instead of life, harkening to the call of the flesh instead of the voice of God. This is the moment when sin is born, and when we fall from a world of unity and completeness into a world of dualities and division—when we drop out of eternity into the flow of human time.

Let’s look a bit more closely at this card. At Eve’s back is the Tree of Knowledge, the serpent wound around its trunk like the Rod of Asclepius, the serpent-entwined staff that symbolizes healing and restoration. At Adam’s back is the Tree of Life. And most importantly, overhead stands the Angel—the apex in the triangle, mediating and resolving the opposition between male and female, spirit and flesh.

This is a card of division and attraction, calling out our division from others as well as the divisions within us. Ultimately, the card imagines the possibility of a union that heals our inmost cleft.

Notably, what attracts Eve is not her spouse, but the Angel. Her eyes are cast upward, while the Angel benevolently gazes down. Adam’s eyes are still on the ground, because his moment of choice is still to come. If he chooses Eve, choosing the flesh and the pull of earthly desire, he will nonetheless be choosing the path to heaven. In his description of the Lovers card in The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, Waite writes: “It is through her imputed lapse that man shall arise ultimately, and only by her can he complete himself.”

Could our desires ultimately set us free? Adam’s world, our world, is continually split in two: flesh vs. spirit, evil vs. good, female vs. male, inner vs. outer, hidden vs. manifest. Can the divisions that beset us somehow be resolved? Can we find our integration? A card like the Lovers suggests that we can.

Our Western creation story explains what we already know in our bones. We are not born whole. Being human is to be divided, and traditionally that division is visible as gender. “Male and female created He them,” as we learn in the biblical story of creation (Genesis 1:27). In today’s society, we’re finally learning to question these normative divisions and the concept of a fixed and binary gender identity itself. But no matter how we redefine identity or question gender norms, the Lovers card grapples with our ingrained sense of incompleteness—and tries to imagine a path toward becoming whole.

Moreover, this card suggests that the path toward wholeness is a path of love. A path of desire, attraction, choice. And yet, love is blind. In the earliest Tarot decks, a blindfolded Cupid occupies the central position in the card. Instead of the mediating Angel, who oversees all, we have the random shot fired by that mischievous son of love and war, of Venus and Mars. When blind Cupid takes aim, who knows where the arrow will land? Again, love is blind. Even when we think we’re freely choosing our path, we’re caught up in our karma and our history. Even in our moments of greatest choice, there are things that are beyond our control. What I want, whom I desire, might not ultimately be a choice I control.

Perhaps our question shouldn’t be how we choose our path but instead can we choose our choices? The Lovers card invites us to find our wholeness by accepting who we are. When we see this card, it’s an opportunity to take our life by the hand, to make peace with our own blindness, and to accept this beautiful world in all its messy entirety, starting precisely right now. Starting precisely just where we are.

Eve looks up toward the heavens—she’s already chosen her path. Adam is still wavering, his eyes on the ground. Whatever our choices are or might be, can we accept the winged embrace of our Angel? Can we accept the blessing that we receive even now, standing just as we are, underneath the shining and sheltering sky?

Harnessing Desire

The path toward wholeness, as we’ve seen with the Lovers, is Cupid’s path. But desire is a funny thing. As Woody Allen famously and very controversially said, “The heart wants what it wants.” 57 And so it does. The world pulls us by the heartstrings, not just when it comes to our choice of romantic partners but at each moment that our blood flows and our lungs fill.

The poet Mary Oliver puts this truth beautifully in her poem “Wild Geese”: “You do not have to be good,” she writes. “You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.” When we learn, finally, to accept what we love and how we love, Mary Oliver tells us that the world calls back, announcing our place “in the family of things.” Our desires connect us to the world, allow us to find our authentic place and our home. And the path of mindfulness is about coming to know and recognize what this body, this heart and mind—this soft and tender animal—loves.

Not that the work is easy. Some desires are harder to accept than others, and finding a skillful, compassionate, safe, and loving way to live with our desires is another matter entirely. This is a dilemma that we seem to face at regular intervals in our lives: when we graduate from high school or college, when we take the plunge and marry or raise a family, when we reach middle age and fall into the famous midlife crisis … Who am I, and what do I really want in my life? We can’t ultimately push away our desires. We can work with them, understand them, reconfigure them, and delay them. We can even resist them. But we can’t ultimately get rid of the ways in which the world elicits and compels us. We can’t ultimately banish the world.

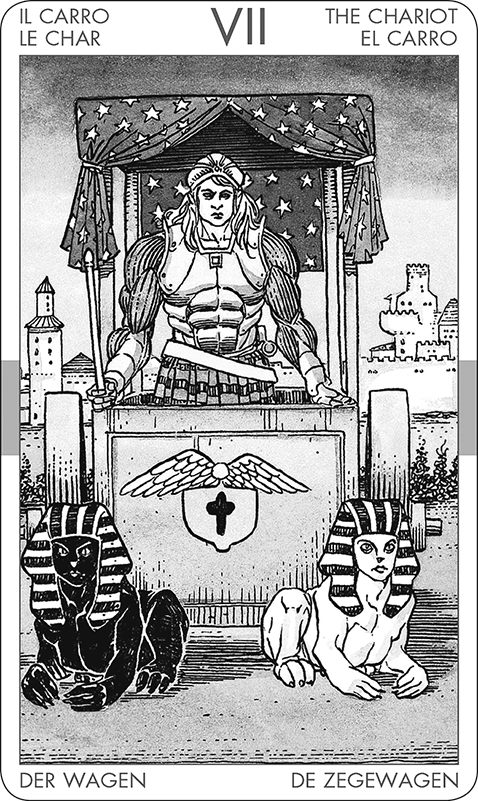

So we move from the Lovers—a card about how we find the path of wholeness—into a card that’s all about the will, about how we drive forward on the path. In the Waite-Smith imagery, the white and the black sphinxes in the Chariot card evoke Plato’s allegory of the soul in the Phaedrus. Plato explains that our soul is like a chariot drawn by two different and not very well-matched horses. One horse, the dark and unruly one, represents our appetites and desires. The other horse, bright and handsome, represents our noble love of the good. I’m pulled in two different directions, by my lower instinct and my higher self. The wise charioteer has to find a way to balance these competing forces.

The Chariot invites us to harness the competing sides of ourselves—the distinctive preferences and patterns, aversions and cravings, that make us human. We don’t get to leave anything out of the equation: the Charioteer needs all the horsepower she’s got. The only way that we can balance these competing forces in our life is to begin by acknowledging them. What does the soft animal of this body, of this tender heart and mind, love? We can only drive our chariot by taking our heartstrings firmly in hand.

The Chariot exhorts us to leave nothing out, to take no part of ourselves for granted. It’s time to lean in.

Facing What Scares Us

Note: In historical decks, the trumps of Strength and Justice are numbered XI and VIII, respectively. In order to conform with Kabbalistic associations, their numbering was exchanged in the nineteenth century by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (the magical order to which Arthur Edward Waite originally belonged).

What makes us strong? The preceding card, the Chariot, traditionally represents the archetype of conquest—conquest in all spheres. The Charioteer who is able to rein in his unruly dark horse shows us “triumph in the mind,” as Waite puts it. Traditionally this conquest is the triumph of reason over passion, of mind over matter.

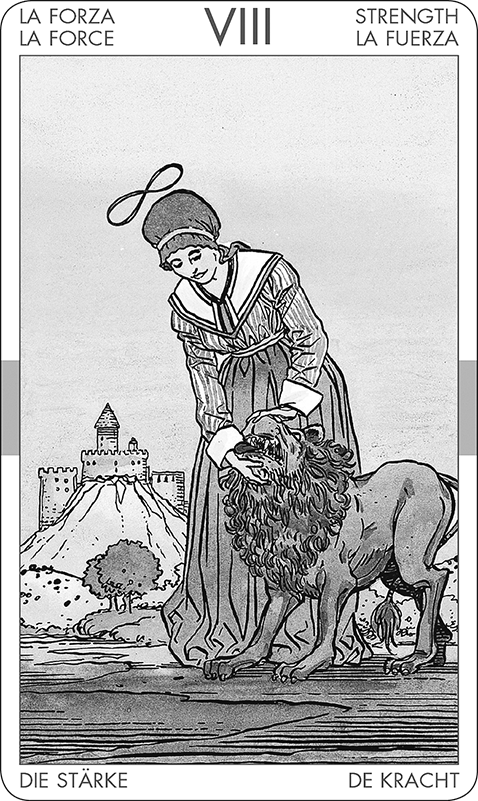

In contrast, the power of Strength (or fortezza, force, fortitude, as the card was known in the earliest historical decks) is not about conquest but instead about relationship. Like the Chariot, this card also denotes the power of the human will, but the power here doesn’t look exactly like mastery. Force forces nothing. The Lady’s face is smooth and calm. Her hands are placed gently around the Lion’s mouth. Waite notes the ambiguity of this card in its traditional iconography: is the female figure opening the lion’s mouth or closing it? Waite chooses to portray the latter, and emphasizes that “her beneficent fortitude has already subdued the lion, which is being led by a chain of flowers.” De Angelis’s illustration for the Universal Tarot omits the flower garland detail but reinforces the gentleness of the Lady by adding a demure bonnet and wide collar. Over her head hovers the same figure-eight symbol for infinity (the lemniscate) that we find with the Magician. Indeed, these are the only two cards in the deck graced by that symbol.

This parallel to the Magician is further emphasized in Colman Smith’s illustration for the 1909 deck. There, the Lady is garbed entirely in white, while the Lion’s skin is vibrant red. Red and white are the Magician’s colors. Moreover, the red blooms of the flower garland wrap around her waist as well as the Lion’s neck, forming a double loop of flowers that echoes the lemniscate over her head. Magician and Strength: what ties the two cards together?

Strength denotes the movement of the human will as a force of alignment. Like the Magician, with his wand stretched up to the sky and the four elements laid out at his side, the Lady harmonizes with her world, joining into dynamic relationship with what otherwise might be separate and threatening. With her face bent toward the beast, their eyes engage. What might have been a dualistic opposition now takes a unitary form, like energy swirling around the two curves of a lemniscate or the two joined halves of the Tao. For many modern readers, the Lion represents our bestial nature, our unreason, our instinctual vigor. It’s another image like the black sphinx in the Chariot card—like the dark horse of desire from Plato’s allegory of the soul. Yet the roots and truth of this card spread deeper than any simple dualism can capture. The Lion is more basic and more powerful than that.

Indeed, the Lion is everything that scares us. It’s everything that we would, if we could, simply reject. The card invites us to weave ourselves together with the things that scare us. We are invited to bind ourselves in the endless loop of the lemniscate, the sign of infinity and of beginnings that wrap back unto themselves. Strength reminds us of the kind of power that doesn’t aim for mastery or conquest but instead finds relationship, weaving together the good, the bad, and the indifferent.

And then finally, there are those pale and delicate hands of the Lady. Tender and small, they are no match for the Lion’s teeth. Strength doesn’t arise from conquest but instead from a vulnerable patience. In this very moment, how might we turn toward the things that scare us? 58

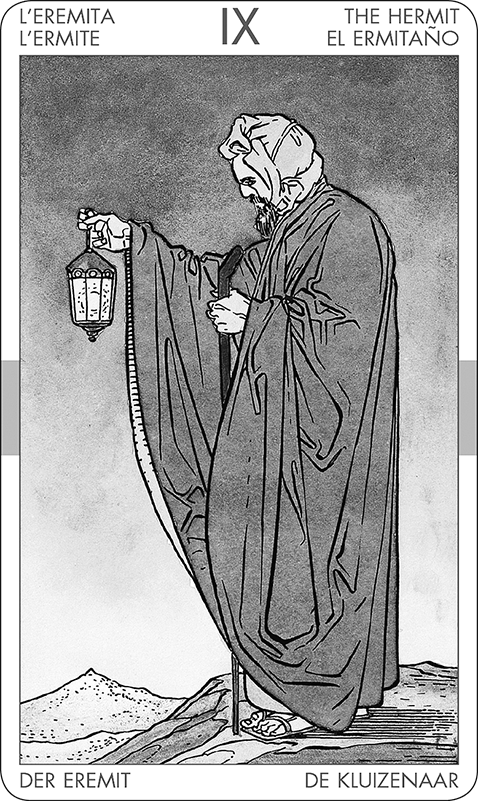

Waiting for Light

How do I light my path forward? Traditionally this card marks a time of inward turning: what the Zen tradition calls “tak[ing] the backward step that turns the light and shines it inward.” 59 The Chariot and Strength have invited us to turn toward the world with the full force of our will and with a heart of patience. Having faced and embraced the world, we now come to a time of inwardness. Or, to put it another way, until we’re able to turn toward the world, turning toward our fears and aversions, our desires and our yearnings, true inwardness is not possible. Now in our patient fearlessness comes the moment to step back to the source of illumination, which never lay outside of ourselves.

Traditionally, then, this card invites a moment of retreat, a time to withdraw from the solicitations and provocations of the world, a time of quiet and contemplation, so that we may find the inner clarity that will illuminate our path. This card recognizes that the real transformation we seek is not going to come from “out there” but instead will need to take root within.

Illumination is a central concept for this trump, but in its earliest depictions, the Old Man carried an hourglass—not a lantern. In his earliest incarnations, the Old Man of the Tarot was a representation of Father Time. How did we get from hourglass to lantern? How did we get from the sands of time to the light of truth? This card suggests that illumination requires the slow, steady passage of time.

We live at internet warp speed, in a world of split screens and slide-overs and infinitely divided attention, and we all imagine that we can move just as fast as our devices. There’s no time to deliberate, no time to think once, much less twice. The world keeps telling us that if we blink and miss a tweet, we’ve missed everything.

Nonetheless, everyone I’ve ever met seems to crave a little slo-mo in their lives, yearning to hunker down and set down deeper roots. Everyone wants more time—by which they seem to mean simply being able to experience more mindfully the time they already have. And when it comes to fellow seekers, we all seem to crave more time to explore what we’re really feeling; more time to uncover what the world needs and what we need to offer. And yet, even we seekers wanting a slower life tend to imagine that our intuition has failed us if our path isn’t instantly revealed in a flash of insight. We feel so easily lost and discouraged, doubting ourselves when the answers don’t come with this weekend’s workshop or that evening’s ritual. We want to slow down, yet we tend to crave the instant epiphanies.

It takes time, the flowing and passing and dedication of countless moments, to take the backward step toward the inward light. Everything I know about the contemplative life is that those epiphanies, those flashes of insight, those moments when the light in the lantern burns bright, arise from long, dedicated, quiet periods of waiting. Quiet listening. Patiently biding time, as the universe unfolds.

The Hermit invites us to wait and be still; to wait as each grain of sand in the hourglass passes through its narrow neck.

How might we cultivate a life that enables more slowness? More heartful, mindful, quiet, and disciplined practice? (For one thing, we can spend more time with our cards!)

Turning Over

In its most traditional representations, the Wheel represents Fortune. By a fickle spin of the wheel, we might be on top today or in the gutter tomorrow. As Heidi Klum, the supermodel hostess of the reality show Project Runway, says, “One day you’re in and the next day you’re out.” You’ve got to admire Heidi’s Teutonic nonchalance when she shows losing contestants the door: “Auf Wiedersehen!” She clearly believes in Fortune’s wheel. You’re out now, but who knows! Her German goodbye literally means “until we see each other again.” The wheel might turn back in your favor! See ya later!

Indeed, in the earliest decks, the figures bound to the wheel clearly depicted the rise and fall of a single person. In the fifteenth-century Visconti-Sforza deck, four figures are bound to the wheel, each one bearing the relevant caption in Latin: “I will reign,” “I reign,” “I have reigned,” “I am without reign.” The figure at the top of the wheel is enthroned and crowned: I reign. The old-man figure at the bottom of the wheel carries the whole turning edifice on his back: I am without reign. Finally, the two figures clinging to each side of the wheel represent rising and falling fortunes, respectively: I will reign—I have reigned. You’re up today, you’ll be down tomorrow. Everything that rises must also descend. Moreover, just like Cupid, Fortune is blind. Her favors are cast, like that arrow from the god of desire, without special aim. And so in traditional imagery she stands blindfolded at the center of her wheel. One day you’re in and one day you’re out. If Fortune could see, she’d no doubt bid us all Auf Wiedersehen!

This traditional depiction of Fortune’s wheel provides a powerful social commentary. What goes around comes around. The king who’s reigning today may well be a beggar tomorrow. And, of course, if he’s down and out, then someone else must have risen to the top of the social ferris wheel. The Wheel doesn’t just depict the fate of an individual. Fortune is always a social and collective force. The king is only king because someone else is not king. My gain is ultimately your loss, and vice versa. Our fates are ultimately interconnected.

Fortune’s wheel is an ancient Western concept. An equally ancient depiction of the wheel can be found in Asian iconography, in the Buddhist image of the wheel of karma. That wheel also depicts the rising and falling of human fate. But at the hub of the Asian wheel, instead of finding the blind force of Fortune, we traditionally find a depiction of three animals who are chasing each other’s tails: a rooster, a serpent, and a pig. The animals represent the “three poisons”—greed, hatred and ignorance—that generate our karma.

The rooster is greed, the pig is delusion, and the serpent is aversion. These are fundamental qualities of our human existence. We’re always grabbing on to things that give us pleasure, holding on as tight as we can, trying to pull the goodies in. That’s the rooster, signaling desire and greed. We’re also always trying to push away what we don’t like, the yucky stuff of life. That’s the serpent, the symbol of aversion. And then there’s the pig, the symbol of our ignorance or delusion. We continually miss the truth of our own nature. We fail to see that our lives are interconnected with everything and everyone else. We fail particularly to see the impact of the rooster and the serpent—their impact on us and on the world around us. For instance, I love my megastore-box-discount-warehouse-club membership more than life itself. My inner pig and my inner rooster dance merrily down its enormous aisles. We lustily buy our cheap and plentiful consumer goods, thrilled to have scored a deal, not thinking about the true cost of those products for the environment, for developing nations, and for our own ingrained habits of consumption and waste. That’s our ignorance in action.60

The Wheel of Fortune in the Visconti Tarot

In the discussion of the Hermit, I mentioned the desire that so many of us share nowadays: we’d like our lives to slow down. The Wheel invites us to slow down. But it’s actually up to us to stop the wheel’s turning. If we want things to change, truly to change, we’ll have to take a good look at our own heart and our own motivations. The Wheel invites us to renew our dedication to the work of waking up: to that journey of self-discovery, of finding greater familiarity with ourselves. The Wheel asks us not to worry so much about life’s ups and downs, not to be so mesmerized by the wheel’s spinning spokes. Instead, this card invites us to think about the wheel’s hub, its center point. Indeed, Trump X reminds us that at the center of this wheeled universe (as Walt Whitman might put it), we’ll find no other fate or fortune than our own heart and mind.61

Might we focus less on what’s happening at the rim and more on what’s happening at the hub? It’s time to turn things over. It’s time to be the change we’d like to see.

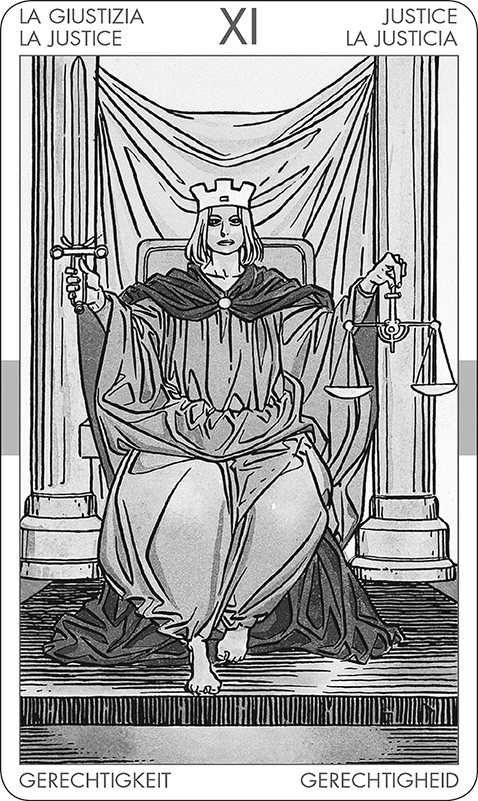

Making Right

Note: In historical decks, the trumps of Strength and Justice are numbered XI and VIII, respectively. In order to conform with Kabbalistic associations, their numbering was exchanged in the nineteenth century by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (the magical order to which Arthur Edward Waite originally belonged).

The urge for justice seems to be almost hard-wired and something that’s shared by other primates and mammals. Capuchin monkeys, apparently, will object to unequal treatment—righteously hurling cucumber slices back at the human researchers if they see their next-door neighbors being given grapes. (See primatologist Frans de Waal’s work.) Justice, as we and the capuchins understand it, requires the ability to weigh one thing against another. We need the ability to compare cucumbers to grapes, and apples to oranges. When we crave justice, it’s because something has gone awry—become uneven—in our world. Something is owed, lacking, broken, stolen, lost. Like the capuchins, we’re hoping that we, or others we love, will get their due. When we seek justice, we’re typically seeking restoration. We want to be made whole. The trump card Justice, however, points us to the deep and abiding difficulties in this mindset. What would it mean to truly be made whole?

In the Tarot, traditional iconography depicts Justice as a deity or monarch. (Justice is actually one of the four cardinal virtues.)62 Justice wields both a balance and a sword. From the perch of the dais on high, Justice offers the true measurement of all things. All things find their place and are regulated in terms of a just and cosmic order—a divine sense of balance. At the same time, the sword allows Justice to discriminate, to carve out the distinctions that enable the divine balancing act. If we’re going to weigh one thing against another, we’re going to have to cleave this from that. The act of Justice requires a capacity for discernment and fine divisions. Justice must slice the world into its various shades of gray so that any given action, any given deed, can be seen according to its true colors.

But, in truth, how can I measure one moment against another? The Hebrew Bible famously identifies justice as the exchange of an eye for an eye. But can we truly adequately compensate for any loss, for any moment of suffering? Do I tell the four-year-old who’s brokenhearted because they’ve lost their doll to get over it, it’s just a doll? Do I tell someone who’s lost a child that they will recover? What would it mean to recover from that kind of loss? What does it mean to recover from any kind of loss? Suffering is suffering. Forms of suffering are all incommensurable.

If we could gaze down on the world as if from the outside—from the perch of a throned and divine monarch, let’s say—then perhaps Justice would indeed be the movement of divine balance. From a god’s-eye view, each thing, each human action and heart, might indeed find its true worth in the cosmic order. But instead, we’re just strangers on the bus, as the singer Joan Osborne might say, in her song “(What if God Was) One of Us”—making choices, discerning our path, trying to do the right thing, trying to be fair and forthright, trying to make good on our word. We’re trying to make right. And we do all these things, as we must, without ever finding that one leverage point, the knife edge of the balance, from which the pans of the scale can teeter and dip—the feather revealing its lightness, the heavy heart sinking instead to the earth.

Now is the time to forgo our efforts to leverage our world—to quit trying to justify our errors, balance out our losses, find solace by placing the burden of blame on somebody else’s shoulders. Apparently even monkeys can feel wronged and seek justice. But justice isn’t a thing to be sought. It isn’t something we can know or enshrine. Justice isn’t a divine force. It’s just the distinctly human activity of doing right, as best we can, and facing whatever comes next.

Justice isn’t something from on high that we uncover. Justice is ours to make or break.

It’s up to us to make the world right.

What, even now, is calling for wholeness and restoration? Without leveraging anything, without trying to trade in this gain for that loss, how might you meet this moment of decision? How might you help your world regain its sense of rightful balance?

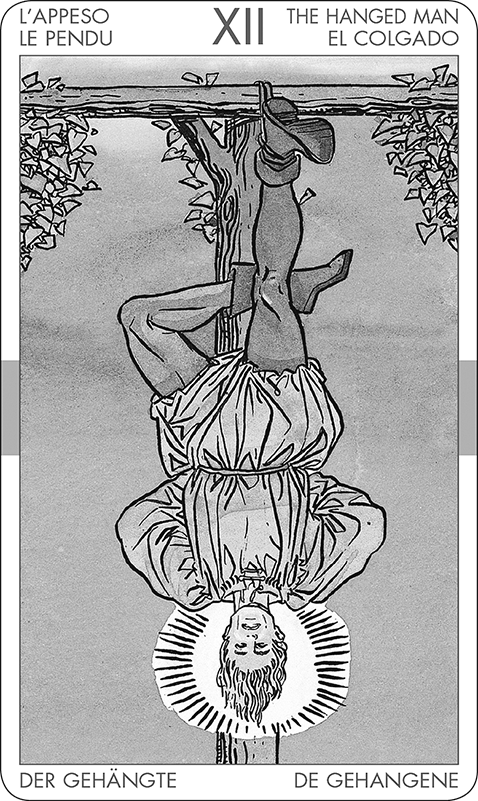

Renunciation

Sometimes life plucks us up by the heel. Those moments are perhaps more common than we recognize. The Hanged Man invites us to explore those times of suspension and sacrifice.

From its earliest versions of this card, the Hanged Man’s legs are crossed in a peculiar way—reminiscent of an inverted Hindu-Arabic number 4. This figure’s suspension, his predicament of being bound and hanged, is, in the first place, an inversion of the energy of the Emperor, the fourth trump and the reigning figure of control and mastery. Accordingly, for many modern readers the Hanged Man represents a revolution in our perspective: an inversion of heart and mind that leads to the suspension of activity and to a retreat from the active life. In other words, what is signaled here is a profound paradigm shift: the Hanged Man changes our orientation in the world from one of mastery and control to something more like surrender.

Here we touch again upon one of the deep invitations of the Tarot pack. Might we simply yield? Might we renounce our efforts to control and conquer and simply give way to the circumstances that arise around us? As we’ve already seen with the Strength card, the position of acceptance and direct embrace can actually provide us with more mastery than coercion could ever achieve—if mastery is the word to use any longer for what looks more like letting go, like renunciation.

But it’s also important to remember that the earliest decks call this card the Traitor. Paul Huson points out that in a variety of early modern decks, in fact, this trump is specifically identified with Judas Iscariot—the ultimate treacherous figure. Yet if Judas is the archetype of betrayal, he is also a figure who ties the card’s meaning even more tightly to the ideas of renunciation and sacrifice. Judas is a traitor whose betrayal is also a sacrifice. Judas’s eternal damnation is necessary for the story of Christ. Without a Judas who betrays Jesus with a kiss, there can be no Christ who saves us all on the cross. At least, so argues the Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, in his short story “Three Versions of Judas.” According to Borges, Judas sacrifices not only his body but also his eternal soul. From Borges’s provocative perspective, Judas’s sacrifice out-martyrs Christ.

The figure of Judas actually inverts everything we might think we know about traitors. His was the ultimate betrayal, but it was also the ultimate sacrifice. Judas gave up Christ for dead, but from another perspective, he himself died—and died eternally—for Christ. Things are not necessarily what they appear. Life sometimes plucks us up by the foot and enforces a different point of view. In those moments it may be painfully obvious what we’ve had to give up. These are decidedly not moments of power. They also aren’t moments of particular strength. The Lady has her Lion, but our Hanged Man is all alone.

Yet for all his solitary sacrifice, the Hanged Man is first and foremost a figure of illumination. The eighteenth-century Zen master Menzan Zuihō once wrote, “If you do not make mental struggle, the darkness becomes the Self-illumination of the brightness.” 63 The Hanged Man has every right to struggle. He’s bound and hanged and, perhaps like Judas, profoundly misunderstood. Ultimately, however, what he renounces is the struggle against his new upside-down life. He renounces the efforts to be right, righteous, and right-side up. And that renunciation sets him ablaze with a halo of light.

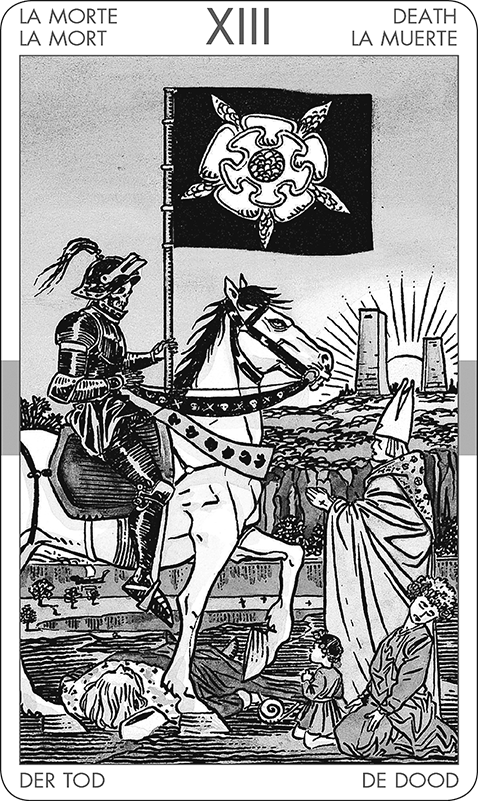

Rising and Falling

“For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings.” So says Shakespeare’s King Richard II, a king who is facing his own weakness and mortality, and who will himself be dead by the end of the play.

The trump of Death recalls the movement of Fortune’s wheel, offering us a picture of change and loss and transformation, and like the Wheel, Death seems to hit kings the hardest. Among the four figures confronting death in the Waite-Smith imagery, it is the King who has fully succumbed, his body, ermine cloak, and crown all trampled under Death’s steed. The trump of Death is the stuff of great tragedies. Shakespeare’s plays are full of sad kings. But as we’ve already seen with the Wheel, we are all players in this great drama. This tragedy is ours. We’re all kings in the kingdom of our minds—and typically we imagine the aging process as the decline of our kingdom, our identity, until Death rides by and we decline into nothing.

Traditionally Trump XIII has a number but no name, because Death’s scythe cuts away everything: all our memories, all our titles, all our props, all the accoutrements of our character. At its most basic, indeed, this card invites us to consider everything we know about ourselves—and to ask what it might mean to let those ideas go. Is it true that we will then be left with nothing? Or will such a death instead leave us on the broad, wide face of the Fool’s cliff, facing everything? With the sharp edge of his scythe, Death offers an opening and openness.

Death brings us the not-knowing of beginner’s mind.

Thus, in many of the early modern decks, where Death wields the iconic blade, below him the field is strewn with body parts—a head here, a foot there, some bones and a few hands. Among the severed human bits, leaves and sprouts spring up, and we are viscerally reminded of the agricultural metaphor at play. Death harvests life so that more life may grow. Letting go of our various identities, of these various parts of ourselves, we find growth. One sprig dies, another shoots upward. Death is about the loss of self, but it’s a loss without which the self withers. Without death, no flourishing or growth is possible.

And the card also invites an even broader perspective. It invites us to look out on the horizon. In the Waite-Smith imagery, we see a brilliant sun in the distance. It’s either rising or setting, impossible to tell which. Indeed, from the standpoint of the horizon, rising and falling are one. It’s all one brilliant world, an entire living wholeness of birthing and dying, of changing and growing, of letting go and grabbing on. It’s all abundance. It’s all the universe. If we keep an eye on this horizon, there’s a stillness that can arise—a waking up into sacredness and beauty and glory and life. Waking up into life as that which encompasses both birth and death, and is as old as the distant mountains and sea.

This is why we practice, meditate, and explore the cards. We practice in order to take root in this abundance—this wholeness at the heart of everything.

This abundance and wholeness is everything.

Reconciliation

From its earliest depictions, this trump portrays a figure mingling the liquids of two vessels. Water is being mixed with wine: a traditional representation of moderation. Temperance doesn’t force us to choose between intoxication and purity. Instead, it envisions a reconciliation or blending of opposing forces.

With the fourteenth trump, the Tarot has again invited us to consider how to work with the dualities that frame our world. The answer that Temperance provides is not, perhaps, very sexy. This trump lacks the Chariot’s vigor of guiding, restraining, and harnessing. Temperance also lacks the patient vulnerability of Strength. Instead, Temperance offers us watered-down wine! Temperance is, in this view, a bit of a wet blanket—the designated driver at the tavern of life, the schoolmarm standing over the punch at the social.

Temperance may not be sexy, but she is vibrantly alive. Temperance is actually the card of spiritual practice. Significantly, where nearly every other trump is depicted frozen in place, perfectly still, Temperance is in the midst of pouring. Flowing water is a part of her, defines her. The card depicts an ongoing, ever-flowing orientation toward the world. Perhaps for this reason, a number of modern interpreters have associated the trump of Temperance with the Buddhist notion of the middle way.

The middle way is often understood through the legend of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha. As a prince destined to inherit his father’s kingdom, and protected by his father from the hard realities of life, Siddhartha spends his first three decades behind the palace walls, luxuriating in all the delights of the material world, indulging every whim and seeking every comfort. He does this because he doesn’t know any better. When he does finally see a bit of the world beyond the palace gates, he realizes that no matter how many walls he builds, no matter how much he coddles and fortresses himself, he will inevitably be subject to sickness, old age, and death. And so he leaves the palace for good, leaving behind the sensuous and comfortable world. He spends the next six years in deep ascetic practice, mortifying the flesh, striving to repress and restrain his bodily nature. In this way he goes from one extreme to the other. Finally, when his body is more dead than living, a compassionate woman approaches him with a bowl of rice milk. He takes, he drinks. He abandons the ascetic life for good. He sits beneath a sisal pine—the so-called bodhi (or enlightenment) tree—and enters into meditation, determined to awaken into the fullness of a human life that neither pushes the world away nor drags the world in tight. What he discovers in that moment is the middle way. He finds the path of practice.

The middle way is often wrongly understood to be the road between two extremes, like Goldilocks choosing what’s neither too this nor too that. But that sort of middle option doesn’t resolve anything. It just creates another dualism, countering the original dichotomy with Door Number Three. Instead, the true middle way is not another option, but instead another practice. The practice of reconciliation.

We return to the flowing water of the Angel’s two vessels. Temperance pours from one vessel to the next. Temperance is an act, a movement, a discipline. Temperance is about fluidity and flow. It’s an active mingling of our life’s currents.

The dictionary tells us that reconciling comes from the same Latin word as council. To reconcile is to combine and come together, just as a council convenes in order to resolve points of difference. The good council of Temperance brings our life into harmony. Temperance reconciles the waters of life. Her work is ongoing, energetic, and even holy. It’s the kind of work that signals our most profound, inalienable connection to the sacred and divine. The trump of Temperance invites us, moment by moment, to claim our birthright: a life of integrity and reconciliation.

How are we harmonizing our life, even now?

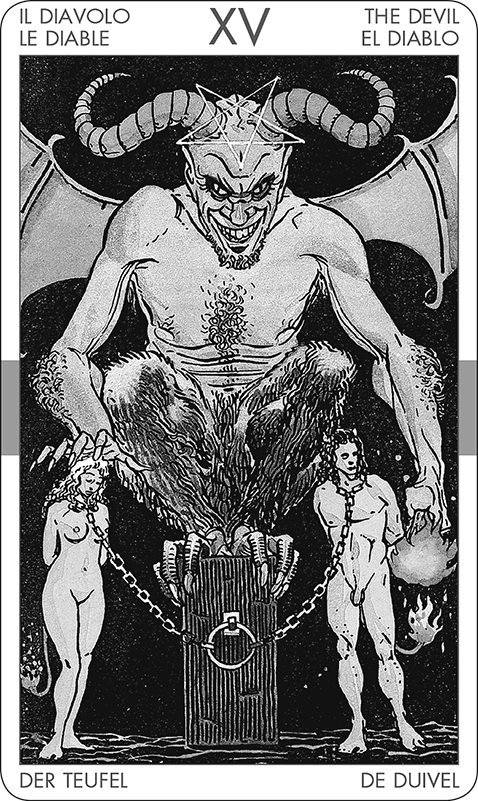

Enfettered

What is freedom? What does it mean for me to feel free? What is liberation?

We Buddhists talk about saving and liberating all beings. We talk about Buddhism as a path of liberation. But instead, I often find myself inhabiting a Ten of Wands universe. Picture the figure laden with her burden of staffs, her burden of tasks. As we’ll see when we consider the suit of Wands, it’s all too easy to throw our fiery energies forward. With the ferocity of the Chariot, I get inspired and drive forth. And then somewhere down the line I find myself with a burden on my back. My “burden” is actually just the world I’ve created by throwing my energy into play. I create my life with each response to the world, and then discover that my life no longer feels like it’s mine. Somehow “my” life passed me by.

How do we lead a life of freedom? That’s the fundamental question of the Devil card.

The Waite-Smith imagery invites us to read the Devil as an inversion of the Lovers. The Lovers card depicts our culture’s iconic moment of choice: Adam choosing the flesh over the word of God. In the Tarot that choice aligns us body, heart, and mind with the divine. Eve gazes up toward the heavens while a beneficent Angel gazes down, arms outstretched to embrace the whole of our worldly and sensuous existence.

The Devil card seems to replay the very same moment from the standpoint of shadow and nightmare. Eve gazes down, Adam looks away, and what might have been choice and freedom is now simply bondage. Instead of an Angel sanctifying our earthly desires, the Devil has put us in chains.

We already know that the Tarot, like us, thinks in dualities. The deck repeatedly shows us two sides of the same coin and invites us to find wholeness and integration. When the Devil appears in our readings, we’ll want to look very closely at the stories we’re telling ourselves. Do we feel overwhelmed? Trapped? Addicted? Helpless? Perhaps we simply feel a bit meh about life, and we’re meandering dull-eyed and indifferent through our days. The Devil card asks us to consider our choices—and to consider what hinders us from experiencing the vibrancy and spontaneity of an unfettered life. That life is already ours, if we could only reclaim it.

There’s a story I often tell my mindfulness students.64 A farm girl’s one chore every night is to make sure that the cows all get back into the barn. Over time she notices that the cows invariably take the same circuitous way back home. Try as she might to whistle and corral them into a more direct path, they seem shackled to the same nonsensical route. She finally learns that the herd developed this path years before to get around obstacles, like the rusting old truck in the middle of the field, the huge drainage ditch, and the place where firewood had been stacked. This behavior has persisted, repeated by generation after generation of cow, even after all the obstacles disappeared or were removed.

We all have “cow paths” in our lives: patterns of behavior that developed in very sensible ways in response to the obstacles and circumstances of our lives. But now these paths may feel more like ruts. They take us further and further away from our true home. What once helped us cope now merely enfetters. How do we reclaim the freshness and vigor of our lives?

The Lovers card invited us to imagine self-acceptance. The Devil card invites us to engage in self-inquiry. It’s time to look around. To investigate the terrain that even now is underfoot. To honor the past choices that have landed us on this path. The decisions we made were, at one time, brilliant. Our cow paths were the only routes that would avail.

But now the present beckons.

Let’s blaze forward in real time.

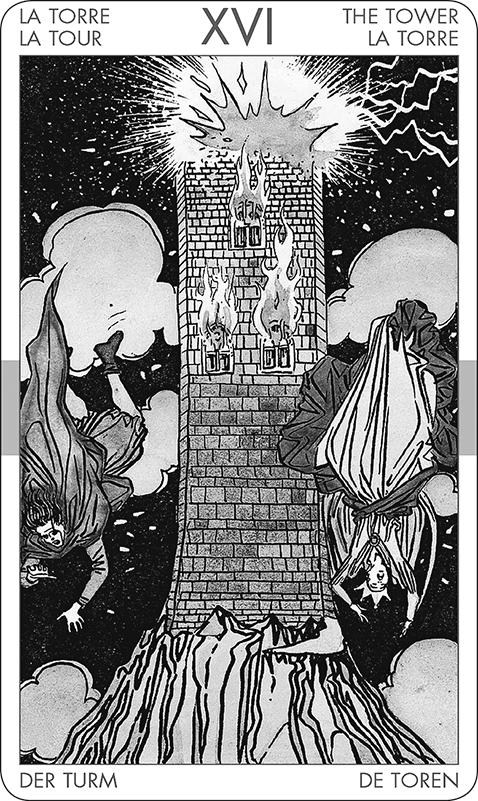

Ignition

In a number of early modern decks, this card is called La Maison Dieu (The House of God), and indeed quite traditionally the Tower calls forth the imagery of the Tower of Babel and what it means for us to strive toward the heavens. The story of Babel is, in a certain sense, a cautionary tale for the seeker. How dare we beings of dust and earth reach for a place in the heavens? More broadly the Tower invites us to see the many ways in which we strive upward and define ourselves and our world with chin held high. In an instant those pretenses, those hopes and dreams, can be flattened. Lightning strikes, the whole edifice crumbles, and we and everyone else involved tumble disastrously from on high. In an instant, life can cut us down.

Very early woodblock depictions of this card show a tower being struck by lightning. In these depictions, the uppermost battlements, now set ablaze and severed from the base, look like the crown of a king. As with the Wheel or with Death, we’re reminded specifically about sovereignty—about the sad deaths of kings. Don’t we all think of ourselves as sovereign in some sense? Don’t we all envision ourselves as stable and self-contained masters of our own destiny? At the very least, don’t we hanker for that kind of stability and independence, imagining that a skillful human life is one lived on such autonomous terms? But the Tower reminds us of how easily and suddenly life can knock off our crown.

Of course, there can be a kind of deliverance in suddenly losing one’s head. This is, in all likelihood, not a moment we would have chosen. We didn’t want this. However, this violent ending may also be the ecstatic burst of a new beginning. The loss of a job, the dissolution of a marriage, even a life-threatening illness or a natural disaster: these Tower moments can emancipate us in ways we never imagined.

And yet, in an important sense, this card actually invites us to shift our gaze. It’s not always about us. We modern interpreters tend to see this card from the standpoint of the Tower. We inevitably focus on ourselves, on the imposing tower-like edifice that is our life and our identity—and that is also subject to bolts from the blue. But in many of the earliest decks, the emphasis is not on us, but on the bolt. Early Italian titles for the card all invoke the Lightning, not the Tower: La Sagitta (The Arrow), La Saetta (The Thunderbolt), Il Fuoco (The Fire). An early French variation is even more direct: La Foudre (The Lightning). These early cards remind us that the tower doesn’t just fall. It is obliterated in a burst of light.

Sometimes change feels natural, cyclical, like Death’s harvest in Trump XIII. But when things really ignite, when upheaval really happens, it happens in a heartbeat. Everything burns up completely. In this way, the Tower is ultimately not a card about collapse. It’s a card about ignition—about the flash of light that can both illuminate and obliterate our world. Indeed, we might even say that it’s a card about enlightenment. In the end, the Tower doesn’t just signal a change in our life. More deeply, it invites us to shift our gaze away from the edifice itself—from the structures we assume are fixed and upon which we tend to rely: identities, institutions, states of nature.

What if we relied on the Light itself?

Faith

The traditional version of this card displays seven stars, perhaps to represent the seven “planets” of ancient astronomy, clustered around an eighth star, which various commentators have identified as the dog star Sirius, the north star Polaris, or Venus, the morning and evening star. Waite is unequivocal: the eighth, central luminary is the Star of Bethlehem, the star that directed the Magi to the baby Jesus. Traditionally the Star is a card of redemption, a card of hope and decisive navigation into the future. The Star illumines a future of safe harbor, peace, and deliverance.

Incidentally, the morning star is also the light that appeared at the end of the Buddha’s time under the bodhi tree. As we saw earlier, the trump of Temperance recalls the Buddhist “middle way.” The middle way can best be understood through the story of the Buddha’s own life, as he swerved initially from one extreme to the other until finally finding a middle path dedicated to meditative and mindful presence. It is said that under the bodhi tree, the Buddha sat so still that not even the tiniest thread of his robe stirred in the breeze. A stillness so complete has nothing to do with rigidity or the cessation of movement. It is instead the stillness of communion with all things. It is the stillness of the spinning earth, imperceptible to all who are earth dwellers. It’s the stillness of a morning on the hills, as the light fog, the purple-gray grasses, the earth, the green caterpillars, and the black bees all together form one complete mandala of life.

As the morning star’s first light appeared, the legend recounts that the Buddha broke the stillness with a simple declaration: “I together with the great earth and all beings awaken at this time.” The morning star signals our mindful awakening to unity with all things.

There’s a deep connection between this card and Temperance. For many readers, both cards illustrate the calm after the storm. After two great upheavals (Death and the Tower, respectively), Temperance and the Star each bring an invitation to find our balance. Both cards offer a blending of flow and stasis. Both cards show us figures with one foot on water and one foot on land, one foot in the watery currents and one foot on terra firma.

Both cards also show us the emptying of two vessels. In Temperance, this pouring is contained. Nothing is lost. The Angel pours one cup into the next. Such is the staid and measured alchemy of practice, a celestial discipline. In contrast, the Star is no angel. With her exposed female body, she is all vulnerable flesh. Unlike Temperance, she just lets the water flow. She empties one vessel into the starlit pool and one onto the ground. She makes no effort to contain the flow, no attempt to mingle and mix, and yet the pool seems to collect everything. Water settles in the grass, forming rivulets that channel clear streams back into the source. This is a wellspring that holds and absorbs all. In her naked and open act of pouring, the woman returns everything she has to this source, without fear or concern. The source is both font and delta, both origin and end.

Where Temperance is the card of diligent practice, the Star offers an image of faith. It is a card that reminds us of who and what we are at the very source of our being.

Can we dwell in this moment of bounty and beauty beneath the open sky? Can we depend, quite simply, on this?

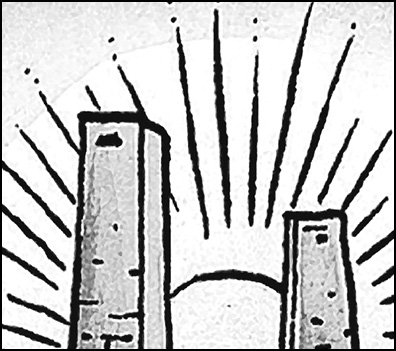

The Depths

“The path between the towers is the issue into the unknown,” writes Waite, in his description of this card. In point of fact, we’ve seen these towers before. They are the towers at the horizon of the Death card, between which a brilliant sun either rises or sets. Here we find a waxing moon (Waite is precise on this point), and although the moon shines brightly, it does so with uncertain reflected light and over the only landscape in the trumps that lacks either human or humanlike figures. Like Trump II, the High Priestess, where the twin pillars define a gateway of sorts—an entrance into the waters behind the veil—this card ushers us into mystery, and invites us to identify the mystery with murky and fluid depth.

Contrast the image of water in this card with the wellspring of the Star. Both cards depict illumined nighttime scenes, but the water in the Star is all surface. Under a moonless sky, the central figure’s foot rests upon the very top of the pool as on a sheet of glass. The water has no depth. In the Moon card, in contrast, the water seems to be entirely depth, without a surface. The crustacean we see at the edge of the waters has no place above air. This landscape devoid of humans, devoid of sunlight, points us toward the mystery beyond the pillars, but the symbolism of the card also makes clear that this mystery will remain beyond our conscious, intellectual grasp. The light of reason has no place here in this card of lunar truth. “The intellectual light is a reflection,” Waite tells us, “and beyond it is the unknown mystery which it cannot show forth.” Like the High Priestess card, the Moon presents us with a gateway, and invites us over a threshold into what cannot be shown forth.

Cards like the High Priestess and the Moon envision spiritual practice as a kind of initiation—an entry into mystery, a passage through a gate. But it’s not so simple when you’re dealing with what cannot be shown forth. In Japanese Zen meditation halls, you’ll sometimes see a sign with Chinese characters that reads: “The Gate of Not-Two”—the gate of nonduality. These Zen placards challenge us to envision spiritual practice as a matter of passing through the Gate of Not-Two. What might it mean, how might it even be possible, for a gateway to give us passage into nonduality? By definition, a gateway separates here from there, inside from outside. By definition, a gateway is already dualistic. The Gate of Not-Two would need to allow us not simply to pass from here to there but to pass from the world of here/there (the world of binary either/or choices) into a world of nondivision, a world of nondistinction between here and there. How would we even know that we had passed through such a gate? There could be no certain bearings.

This is the landscape of the Moon card. It invites us into a place of unknowing, into mysteries that will remain mysterious, into nondual depths that by definition cannot be plumbed. The figures in this lunar landscape have been identified by many, including Waite himself, as representations of our unconscious mind. From a Jungian perspective, this is the world of soul and the collective unconscious: the world of archetype and myth. Many modern readers go on to identify the Moon as the card of intuition. That seems just right to me, but only if we recognize that intuition invariably courts error. It’s all too easy to turn intuition into another form of knowing—like calling pork “the other white meat”—as if intuition could do the work of reason from another angle, yielding reason’s same fruits of clarity and certainty. When we enter the Moon’s nocturnal world, we face the possibility of complete delusion. This is not a world of measurements and comparisons, of right and left and good and bad. There’s no Justice here, no Emperor-like order, no bourns or limits. There’s nothing that will keep us from taking projections for reality and fears for truths. These are the risks that the Tarot invites us to take, not because the Moon will lead us toward greater knowledge and mastery but because it will lead us into ourselves, and into greater intimacy with the vast emptiness out of which all that can be known arises.

If the High Priestess invites us into unknowing, the spectral beams of the Moon lead the way. There will be no guarantees, but there will be great intimacy in these depths.

Restoration

This morning I arose to thick, enshrouding fog. The hills and the wild flowers, the stones and the sea, were all erased by the gray. Even the birdsong and the pervasive hum of the bumblebees were somehow muffled by the moist steely sky. By midmorning, the fog had burned off. The world awoke again to the golden and incredible furnace that allows all of us to thrive and to grow, that illuminates everything, that makes it possible for us to see the very corners of our world, the very corners of our heart.

After the Moon’s invitation into the watery unknown, the Sun greets us with the light of the everyday. In Marseille-style woodblock decks, this card depicts two barely clothed children playing near a low wall, perhaps inside a walled garden. The Waite-Smith imagery picks up a variation on this theme, showing us a naked child on horseback, bearing a scarlet standard. The Marseille style emphasizes the card’s link to community and to the welcoming life of the everyday. The Waite-Smith imagery recalls the mounted vision of Death, who also bears a standard in that deck. Like Death, the Sun rides triumphantly. Indeed, we’ve already glimpsed the Sun’s triumph in the illuminated horizon of the thirteenth trump. As the ceaselessly generative furnace of life, the Sun is already part and parcel of the transformation we call death.

Detail of the rising/setting sun in the Death card

The imagery of childhood is essential to the Sun. We find naked sun kids in the earliest depictions of this card. These children portray a delight and a freshness, an innocence that we might want to associate with new beginnings. And, of course, the imagery of the walled garden can’t help but evoke the garden of our beginnings: Eden. But the Sun is less a card of beginnings than it is one of restoration. The sun, as Shakespeare once wrote, is “daily new and old” (Sonnet 76:13). As ancient as the cosmos, it nonetheless arises fresh each morning.

Indeed, the sun’s old-new freshness recalls the Zen saying that mountains are mountains and rivers are rivers. Before we begin our spiritual practice, mountains are just mountains and rivers are just rivers. We take the world—and our concepts of the world—at face value. The world, we assume, is exactly as it seems to be. After diligent practice, however, we come to see through mere concepts and appearances. We recognize the partiality of our ordinary views. We understand that mountains are not mountains and rivers are not rivers. Disillusioned, we come to face our ignorance.

But with still more diligent practice, we find our way back from ignorance to grace. Mountains are just precisely mountains. Rivers are just precisely rivers. The world in its partiality is also the world in its wholeness.

If we live fully, ardently, authentically enough, innocence can be restored. Paradise can be regained. We can come back to things exactly the way they are, only now seen in their wholeness. We can now see every angle and corner of our lives. What was in shadow before is now fully illumined.

The Sun is a card of culmination, of our life lived to its fullest. We’ve gone through the shadows, we’ve walked through the gate, and we’ve found ourselves right back where we started.

The Trumpet Call