The Four Suits and the

Boundless Abodes

The French occultist Etteilla was the first to commission an illustrated Tarot deck to be used specifically for divination. His 1789 deck was also the first to relate the elements—earth, fire, water, air—to the four suits. Tarot artist and historian Robert M. Place calls this deck “the first modern tarot,” 29 but it wasn’t until the broad occult synthesis of Éliphas Lévi, a French Kabbalist writing in the mid-nineteenth century, that the decisive elemental associations were finalized. When the Waite-Smith deck was designed in 1909, these associations became the basis for each suit’s scenic illustrations, for their distinctive palettes and landscapes. The elements, alongside their correspondences with other components of Lévi’s synthesis (e.g., from Kabbalah and astrology), also formed the basis for each suit’s association with a distinct realm of human experience: mind, soul, will, or body. Grays, whites, and blues signaled the mountainscapes of Pamela Colman Smith’s Swords, with their elemental association of air and their reference to thought and judgment. Her liquid rainbows and golden yellows graced the Cups, associated with the element of water and with feelings and soul. Desert reds and browns announced the salamander fire of the Wands, the suit of will and imagination. And the Pentacles, in many ways the fundamental suit—and for me, the starting point of Mindful Tarot—became the suit of the element of earth, the economic and material world, and the human body.

Earth, fire, water, air.

Body, will, soul, mind.

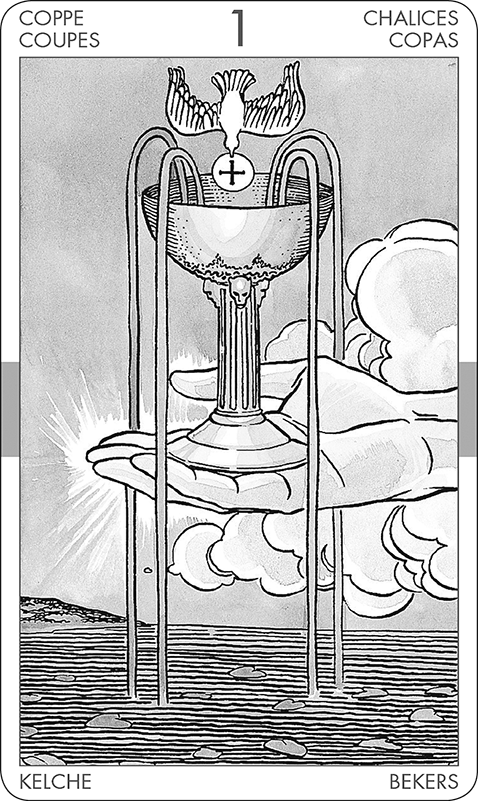

The Aces in all four suits: Pentacles, Wands, Cups, and Swords

The Waite-Smith associations derive from a Western Neoplatonic hermetic tradition.30 But there’s a certain universal logic to these distinctions, and we find similar elemental associations within Eastern philosophy. In fact, the four Tarot suits map neatly onto the fourfold teaching of the Boundless Abodes. In their progression from Ace to King, each of the four suits in turn explores another aspect of the boundless heart. In part 2 we’ll work our way through individual card meanings, providing an integrated system that can be used in ongoing Mindful Tarot practice no matter what deck you have at hand. For now, let’s just quickly survey the land.

Care: The Abode of Pentacles

The First Abode maps the landscape of the caring heart. Care begins at home, it is said—and indeed, this first attitude is all about what it means to come home; to recognize a place as home. I remember the first apartment I rented after graduate school. I was living cheaply on the outskirts of one of the poorest neighborhoods in my city. Whole city blocks were condemned and crumbling. Buildings were in rubble, windows missing and boarded up, dandelions sprouting through the sidewalks and spiky weeds overtaking cracked pavement and patios. But what struck me most of all was the garbage and the litter. The streets, sidewalks, and empty lots were all covered in trash: broken dishes and abandoned mattresses, random scraps of furniture, decaying food and food wrappers, cigarette butts, tin cans, broken bottles, newspapers. The area had devolved into a garbage heap and junk yard.

The Pentacles: tending the garden of the caring heart

This was not a place that anyone claimed as home. Why pick up your trash, why find a garbage can, why take any care at all if a place does not belong to you—and if you yourself have no place? This part of the city was clearly dying, or perhaps was already dead. Depopulated and despairing, this was a place where no one cared.

It’s no accident that this example involves poverty and dispossession. Economic questions are central for the caring heart. After all, the word economy itself derives from the Greek words for home and law. Care begins at home, with the mindful rule of resources—with a recognition of the give-and-take required for all to thrive. If a society’s economic system is skewed so that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, systems of care break down and homelessness becomes not just a fact experienced by a few but an existential reality experienced in some way by all: a restlessness and uneasiness that an entire neighborhood, region, country, or culture can feel.

In contrast, after my morning coffee here on Ikaria, I walk down the side of our hill and run into my neighbor Stavros. His face, chapped by wind and creased with age, opens into a broad smile. I met him only the day before, as he was carefully harvesting dandelion greens by the side of the road, but he waves joyfully as if to an old friend. Ikaria is a rugged island of subsistence farmers, beekeepers, and artisans. Thanks to unpredictable weather, steep terrain, and rocky beaches, tourism is relatively low. Villagers work together, repairing the steep sandy roads when they wash out, laying water hoses for DIY irrigation down from the mountaintops, sharing homemade wine and tsipouro, a potent home-distilled spirit, and often bartering for what they need.

To be sure, there are supermarkets and cable TV and cell towers. But a friend of mine who has been coming to Ikaria for years told me that I would find few souvenirs to take home from the place: “It’s hard to spend money on Ikaria!” For centuries, Ikarian coasts were raided by pirates—and not the nice Keira Knightley and Johnny Depp kind. Piracy drove the villagers inland, up into the mountains. The island has had a spirit of mutuality and cooperation for centuries. There seem to be no police on Ikaria.

Today, Stavros is pruning grapevines in his terraced yard. Another recent acquaintance, young Aristedes, who owns the little market in town, manages a bucking and sputtering gas-run hand tiller in Stavros’s yard. “Aristedes!” It’s thrilling to me that I actually recognize someone in this unfamiliar new place. Aristedes’s English is very good—far better than my phrase-book Greek. “Are you and Stavros related?”

Aristedes looks puzzled at first.

“Uncle, father …?”

Aristedes shakes his head. “Yes. No. Just friends.”

Ikaria is a place where everyone is, on some level, related. Where everyone is at home. This is a place where a 25-year-old grocer tills the land for his 75-year-old neighbor.

What does it mean to “take care”? Can we truly take care of ourselves without simultaneously caring for others, human and animal, and for the earth that supports us all? The suit of Pentacles helps us explore these questions, teaching us that the caring heart finds itself concerned with self and other, with scarcity and generosity, with community and exchange. Historically, the Pentacles were the suit of Coins—and the Waite-Smith imagery invites us to investigate the links between the symbolic exchange of money and the natural exchanges of earth, garden, and harvest. Whether natural or humanmade, exchange itself always requires two sides: this is exchanged for that. Quid pro quo. A central concern for this suit is whether these two sides can remain in balance. Will any given exchange be equal, fair, sustainable? The possibility of a healthy balance is neatly summarized by the Waite-Smith imagery of the juggler in the Two of Pentacles.

Two of Pentacles: a life in balance

There are two sides to every coin, and our juggler allows us to see both sides at once. His two pentacles are tied together with a single cord, forming a lemniscate: the figure-eight image associated with infinity and reminiscent of the symbol of the Tao, where the opposing sides are harmoniously balanced and intertwined. Balance requires a commitment to interconnection and a commitment to the dance—to the juggling movement of exchange. In the original Waite-Smith depiction, the backdrop for the juggler’s dance is a wavy sea with two ships sailing on the swells. One ship rises; the other falls. Can we learn to find our balance in the midst of life’s ups and downs?

Care is also, ultimately, about paying attention. First and foremost, care begins as mindfulness. We learn to care—truly and deeply care—for ourselves by turning toward all of our experiences. And mindfully we keep returning, whenever our attention wanders. Care requires that we welcome even what is not so welcome. The First Abode is the realm of Rumi’s “guest house” all over again: “This being human is a guest house. ⁄ Every morning a new arrival. [ … ] / Welcome and entertain them all!”

Compassion: The Abode of Wands

In Zen, there’s a famous teaching story about Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion. Bodhisattvas are a bit like angels or saints in Christianity: they can be taken literally and venerated, if devotional practice is part of a person’s spirituality, but they can also be understood as representations of important ideas. Guanyin represents the qualities of compassion and mercy. Her name means something like “the one who hears the cries of the world”—and indeed, she is sometimes depicted with a thousand arms and eyes, because it takes a lot of dexterity and vision to respond to a world as crazy as ours!

The Wands: kindling the responsive heart of compassion

The story goes like this. One Zen master asks another, “How does Guanyin use all those hands and eyes?” The answer comes back: “It is like someone in the middle of the night reaching behind her head for the pillow.” 31

When we’re sleeping or half-awake, our minds drifting in the darkness, our bodies still somehow know how to respond to our needs. We flip to one side or the other to ease our back, we pull the covers up tighter when we are cold, and we grab a fluffier pillow to rest our neck. We reach into our environment easily. We respond without thought. Arms, head, pillow, bed: they’re all part of one world of sleep. We don’t need to see clearly, reach broadly, or think deeply. We don’t need to form a plan of action and execute it. We don’t even need to be awake!

Everything is interconnected in the world of sleep—body, pillow, head—so responding is easy. It’s spontaneous and natural. This is what it means for the angel of compassion to have thousands of eyes and hands. Her whole world is one of responding and interconnection. Or, as the Zen master concludes in this teaching story, “Throughout Guanyin’s body are hands and eyes.” 32 She responds to the world with every fiber of her body, because every fiber is also connected to the world.

There’s something completely natural and automatic about compassion. Compassion is the hand that scratches the itch. Compassion responds, at first, by mere reflex. The body naturally tends to its own immediate needs. We itch, and we scratch. But why stop there, confined by the limitations of our own two hands and itchy skin? We first learn compassion by learning how to be kind and responsive to ourselves, but who or what isn’t part of this body and mind? Whitman characterizes the heart of compassion perfectly in “Song of Myself”:

Every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

[ … ]

My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air, …

[… ]

Whoever degrades another degrades me,

And whatever is done or said returns at last to me.

Who or what isn’t a part of this one great body? Our planet holds us all to the earth with the same force of gravity. Plants and animals alike breathe in this one atmosphere and renew it by breathing out. The plants yield the oxygen we need to thrive; we yield the carbon dioxide so vital for the plants. Thanks to this great circle of breathing out and breathing in, can anything be excluded from Guanyin’s body? Those thousand hands touch everything.

Compassion relies on the active quality of response, the scratch that comes unbidden to meet the itch. Discomfort and distress energize the compassionate heart, spurring it into action. But compassion’s activity must be rooted first and foremost in careful attention. If we don’t first notice and attend with care, we find ourselves reacting instead of responding. We find ourselves “acting out.” That’s why the bodhisattva of compassion is named “She Who Hears.” We act recklessly if we don’t listen first. Indeed, true compassion requires, above all, that we take care. In other words, compassion is made possible by mindfulness. As its foundation, compassion requires the mindful attention cultivated in the First Abode. In this way, the abodes build on one another. Each one stands alone as a crucial feature of the generous and joyful heart. But each also stands necessarily alongside the other three abodes—each serving, in turn, as a step in developing and expanding one’s capacity for love.

At its core, then, the compassionate heart strives to relieve suffering, and can be drawn into strife and even battle in an effort to ease the anguish of others. The compassionate heart can be gentle and sweet when the response requires a soft touch. Thus, like Mother Mary, the bodhisattva of compassion is often personified as a female, all softness and flowing mercy. But equally often, the bodhisattva finds form as a male figure of great power. As an ancient scripture puts it, “Precepts from his compassionate body shake like thunder.” 33 Compassion may be mild, but it certainly is not meek. Indeed, active response, its most distinctive feature, has the quality of spark or fire. If care is tended, like a garden, compassion is kindled, like a fire. This fire also characterizes the heart of a true warrior. Compassion is a knight who rides in the service of others. The compassionate heart is a spiritual warrior.

In Greek, the word for generosity is gennaiodoria. During my time in Greece, I’ve been told that the word literally means “brave giving.” Exactly! It’s just this quality of gift that characterizes the bravery of the compassionate heart. There’s no self-contained ego here, no lust for power or for the upper hand. Instead, the compassionate heart generously extends itself to provide relief and solace as needed. The compassionate heart gives bravely.

In this day and age, when protests and petitions seem to be sprouting at every turn, the compassionate heart might also be the heart of the activist. There’s a lot to get active about: climate disruption, economic collapse, political unrest, warfare and mass violence… In such times, anger can be a sacred fuel. When we see suffering or injustice and know down to our toes that something must change, that something must be done, feeling a sense of outrage can be liberating. But it’s so easy to mistake the fire of righteous indignation for the spark of compassion. It’s so easy to get this wrong, and to burn to ashes precisely what we’re hoping to save. It’s hard to be brave, but it’s even harder to be generous.

The suit of Wands helps us explore the bravery of compassion. Wands is the suit of fire, will, and creativity. The Wands teach us not just how to welcome our world (that’s the lesson of Pentacles) but also how to meet it with generous bravery—with an appropriate and transformative response. The suit of Wands speaks to activists, artists, warriors, and even healers. For a long time now, my favorite card in this suit has been the Seven of Wands. Folks often refer to the Seven as the “stand your ground” card. Following the Waite-Smith imagery, it depicts a lone fighter holding off six unseen opponents with his single staff. His bravery is real because he is outnumbered. But it’s also realistic because he stands on higher ground than his assailants. He has the advantage in this battle. The traditional message of the card is one of encouragement during a time of duress. Although you are under attack, you have the high ground and are likely to prevail.

From the standpoint of Mindful Tarot, the Seven of Wands invites us to consider what the high ground in this battle might entail. What are we fighting for, and how are we fighting? Does compassion guide us? Will our actions kindle change, or will they burn the world to ash? Can we stand our ground without turning our back?

Seven of Wands: What am I fighting for?

Cheer: The Abode of Cups

Cheer is something of an old-fashioned word. Nowadays, we mostly use the word in just a few circumstances, like when we clink our glasses (“Cheers!”), root for the home team (“cheer them on”), or lift someone’s spirits (“cheer them up”). Sometimes we talk about “a little too much Christmas cheer” (cheer can also mean festive food and drink) and swear we’ll have less eggnog at next year’s holiday party. But despite the eggnog, we also believe that being full of cheer, cheerful, is a good thing. To be cheerful is to be happy. But it’s a specific kind of happiness. Cheer is joy as a frame of mind. Cheer is not so much a feeling as it is a fundamental approach to life. It’s an attitude, like all of the abodes. When we’re cheerful, we approach life with a light heart, seeing its potential and opportunity. Our glass is half-full rather than half-empty. We see the loveliness of the world, and we cherish its perfections. Where the compassionate heart seeks to end suffering, the cheerful heart seeks the continued flourishing of life. Compassion heals; cheer celebrates.

The Cups: blessing the grateful heart of cheer

For us moderns, cheer is hard to fully grasp. We tend to think about emotions as personal, internal events. For us, emotions are so firmly tied to our own individual experience that we’re sometimes not even sure whether another person can ever know or understand them. In an act of love, I can give you my favorite possession—“I want you to have this!”—but my feelings, which are more intimate and inward than anything I own, are things I can “share” but can never give away. At the end of the day, my emotions seem to remain on my side of the existential fence. They may arise in response to external causes, but ultimately my feelings reside within me, separate from the world “out there.” Of course, I can tell you how it is for me. I can share my feelings. But you’ll never actually know how I feel, firsthand, from the inside.

In contrast, cheer somehow crosses the existential fence. Feelings are private, even when we share them with others. Cheer is public, even when I feel it alone. As I sit tonight on a solitary hillock, looking at the Ikarian sunset, joy bubbles up. I watch the orange dip into the sea and tinge the sandy cliffs and stone cottage walls. I am all alone, but at its core, my solitary cheeriness is about a life lived with others. It’s about belonging and rejoicing. My joy at seeing the Ikarian sunset is part and parcel of my connection to this place. What cheers me is my kinship, even if it’s only temporary, with this community of artists and anarchists, of foragers and farmers, poets and pensioners.

In its earliest historical uses, cheer is about the kindness we show a stranger and the food we eat with others. The word derives from the Middle French word chere, which means “face” or “outward demeanor,” and comes to mean the way we turn toward others, particularly in times of celebration and festivity. It’s perfect that the 1980s sitcom starring Shelley Long and Ted Danson was called Cheers and celebrated a bar “where everybody knows your name.” Cheer fundamentally takes place in community. In fact, we might even say that cheer is the experience of community. It is the experience of a heart that embraces and feels embraced by life at large.

Over this past week, winds have whipped across the island’s peaks and valleys. A few islanders mention their concern about water. “Too much wind,” one innkeeper tells me. “Not enough rain, and the wind dries up the rain when it does fall.” Despite its rough terrain and high mountains, Ikaria is normally verdant and lush, an oasis among so many of the sun-baked islands of the Greek archipelago. This island helps me understand the magic of water, life-giving water: water that flows into cisterns, gathers in pools, seeps into gardens, and feeds the crops, the livestock, and ultimately us humans. Water fills whatever shape it encounters but is never defined by that shape. Like a womb, a vessel may contain water, but the water itself is life. Its nature is to flow and be shared.

Ace of Cups: the waters of life

It makes good sense that the suit of cheer, the suit of Cups, is also the suit of water, and of intuition, sense, and soul. The Cups help us explore that side of us that communes with the very source of life. Even in the oldest Tarot decks, this suit harkens to the imagery of the Eucharist. The Ace of Cups offers a reminder of the Last Supper (itself a festival meal: Passover) and of the cup with which Jesus urged his disciples to remember him and remain in brotherhood. The Waite-Smith imagery of this Ace shows us a cup overflowing and an explicit reference to Holy Communion: a dove (image of the Holy Spirit) bearing a communion wafer as it dives into the center of this flowing stream. The image is one of profound blessing, of inexhaustible life. What does it take to feel such a blessing? How can we taste these life-giving waters in a world that also knows suffering, heartache, and woe?

The lesson of the Cups is gratitude. After grappling with a world in need of care and compassion, the Cups offer the sweet balm of thanks.

Calm: The Abode of Swords

Nearly everyone who comes to me for meditation instruction or Tarot reading is seeking the same thing: peace of mind. If the mind is like an ocean, foamy and churning with the currents of our experience and the swells of change, then the peace they seek should be something like a still sea, right? A placid surface and a quiet depth. No whitecaps, no raging surf.

The Swords: grasping the expansive heart of calm

Sounds soothing, doesn’t it? Unfortunately, that isn’t peace. That’s a world without life.

The sea churns because the winds move, the planet spins, the air pressure and temperature rise and dip, water evaporates and falls, and the tug of the moon scoops the tide up and back, carving out our coastlines. The peace we seek comes, somehow, from making our home in the midst of that coursing energy. In fact, that’s what the word calm originally meant: a shady resting place in the middle of the heat of day. 34 How do we find our shade, our stillness, in the midst of a sometimes scorching, always surging life?

I’ve learned the most profound lessons about calm through my work as a hospital chaplain. I still remember my very first night on call. I spent twenty-seven hours at the hospital, and although the emergency department was relatively quiet that night, adrenaline kept me awake during the entire shift. My only venture into the outside world was during a fire alarm in the early morning. That day and night, I felt a widening sense of paradox and contradiction taking root inside me. The hospital is real and unreal. It is both artificial and completely, relentlessly true to nature. The fluorescent lights, the wires and tubes, the needles and medicines and endless hum of machinery: everything about a hospital feels unnatural. But the hospital is also the place where most of us encounter the starkest, truest facts of our natural existence: birth, death, the fragility of our flesh and bones. The hospital is hermetically sealed and, accordingly, sterile and lifeless. But it is also teeming with lives and stories. It is muffled and silent, although it is pierced by sirens and sobs and fire alarms.

And then there’s the “cave,” as we call it: the chaplains’ staff office itself. This dimly lit, windowless room of cubicles and computers serves as our hermitage: the shelter created to sustain our work in the land of contradictions and distinctions, of living and dying, of nature and artifice. We walk and lurk the floors. (Our work is “holy lurking,” an ICU chaplain once told me.) We visit patients and staff and families, then retreat, after a certain time, to the office. We write chart notes. Drink Pepsi. Share our stories. And then we dive back out again. The office is indeed our calm in the midst of the storm and burning heat.

This is a chaplain’s job, first and foremost: to taste and know calm deeply—so that it can be carried onto the wards, into the trauma bays, out into the world. The calm becomes a chaplain’s tabernacle, a portable chapel, a diving bell to make possible the spiritual work of fine discernment; the work of helping a family say goodbye, for instance, or of helping a patient greet their new normal after surgery or a diagnosis. To discern is to make distinctions, to recognize that this is not that. To discern is to recognize the task of the moment, and also to recognize that we must thereby be prepared to let go of other tasks and other moments. To discern, and discern well, is to live squarely in the midst of the contradiction that is most fundamental to being human: we are creatures bound by time and space (our little lives rounded with a sleep, as Shakespeare would say), but we are boundless in our hearts and minds.

I remember standing with outspread arms one night in the corner of a trauma bay as a team of nurses and doctors worked to save the teenage victim of a car accident. There was nothing for me to do at that point. I had already called the family; the mother was on her way. After a few gurgled words, the boy had fallen completely unconscious. The trauma team was working at full throttle. No one was looking to the chaplain for any spiritual succor. So I held my arms wide, trying just to embrace it all.

In that moment, nothing was more important than saving that boy. Nothing was more important, although from a broader perspective, the work is all futile. Everybody dies. Night after night, the trauma team saves lives—knowing that all lives are saved only for a short while. Ten more minutes, months, decades: in the grand scheme of things, all our lives are short. Like all of us, the boy would ultimately die. And indeed, that night, that particular boy did die. During my time at the hospital, I’ve seen many others who’ve been saved. But not that boy, not that night. And when his mother arrived, and I brought her in to see him, I stood quietly in the corner as she wailed; as she crawled up onto the gurney to rest beside him. I don’t think I’ve ever heard grief so raw and heart-rending. In that moment, nothing was more important than ensuring that this mother did this one last thing on this horrible night: that she said goodbye to her son.

Such is the Abode of Calm. The shelter it provides brings together all the elements of the three other abodes: the mindfulness of taking care, the responsiveness of compassion, and the gratitude of cheer. To these three, the calm heart brings discernment, taking in the peaks and valleys of our world. Its task is to survey the whole: to keep the eyes and heart open wide, and thus to learn how to recognize things as they are, in all their complexity and contradictions. This calm discernment weighs our experiences, is closely allied with the movement of justice and with acts of judgment and communication, and acknowledges the contributions of cause and effect in all phenomena.

Fundamentally, the calm heart assents to the world as it is.

In every moment, the calm heart learns to say, Yes, it is so.

The central risk of this work is detachment. It’s so easy for a calm and even-handed approach to drift into cold indifference. It’s this dilemma that the suit of Swords helps us explore. Swords is the suit of air, and of mind and thought. This suit speaks to our ability to gain perspective: to take a long, airy view of our circumstances. And like that other “pointy” and difficult suit, the Wands, it’s easy to make mistakes. With Wands, the risk is to mistake righteous indignation for true compassion. With the Swords, the risk is to mistake indifference for equanimity. A discerning mind is a double-edged sword, like the suit mark of these cards. If we’re not careful, compassionate, and grateful for our insight, our efforts to gain perspective can cut us off from the world around us. Our supposed calm might only signal that we’re disengaged.

Hence the intricacies of the Five of Swords. For some interpreters, this card is the cruelest card in the cruelest suit of the deck. In The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, Waite’s keyword meanings are decidedly negative: “Degradation, destruction, revocation, infamy, dishonor, loss, with the variants and analogues of these.” His description paints a scene of dishonorable victory: “A disdainful man looks after two retreating and dejected figures. Their swords lie upon the ground. … He is the master in possession of the field.” As in the Seven of Wands, a lone figure confronts a greater number of opponents. But unlike our Wands warrior, this Swords figure is “disdainful” and his opponents “dejected.” There is no valor in the scene. Indeed, this defeat seems to have entailed no actual fighting. Our victor’s clothes are immaculate, and all the blades are without mark or stain. There’s something profoundly unsatisfying, unsettling, about this scene.

Five of Swords: double-edged victory

The Five of Swords encourages us to take a calm, wide-angle view—and when we do so, what we see changes everything. There can be no victory without defeat, no winners without losers, no honor without disgrace. And consequently, there can be no finality to this conflict. The battles will continue. The degraded who have lost everything have nothing left to lose now.

What will we do with this knowledge?

29. Place, The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination, 54.

30. I am especially indebted to Robert M. Place’s careful study of this topic throughout his books and decks.

31. I’m paraphrasing case 89 in The Blue Cliff Record, 489.

32. Paraphrasing case 89 in The Blue Cliff Record, 489.

33. From “The Universal Gateway,” chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra. The male personification of compassion is typically known by his Sanskrit name: Avalokiteshvara.

34. See the Oxford English Dictionary’s discussion of the noun calm. Editors cite medieval terms for shade and rest—e.g., the Provençal chaume (“resting-time of the cattle”) and the Romansh calma (cauma, “a shady resting-place for cattle”)—and link these terms to the Greek καῦμα (“burning heat, fever heat, heat of the sun, heat of the day”) and its derivative, the medieval Latin cauma. See, for instance, the Latin Vulgate’s description of Job’s tribulations: “My skin is black upon me, and my bones are burned with heat [cauma]” (Job 30:30).