The four suits map the four interrelated qualities of the boundless heart. We might also call this heart “settled,” for it characterizes a seeker who has settled in, coming to rest at home in the world, taking care of what comes and goes, responding to authentic needs that arise, rejoicing in the gifts of the present moment, and calmly embracing life in all its complexity and contradictions.

Care, compassion, cheer, and calm. These four qualities describe the settled heart: the heart that rests at home in the world.

I’m always amazed that our minds and bodies somehow do know how to settle down. Somehow we know how to rest and find quiet. Not perfectly and not always. But over time, more or less reliably, if we ask ourselves to slow down and take a moment of rest, our muscles and hearts do somehow soften, lengthen, release—prompted by the gentle tug of the heavy earth.

Once, over a Rolling Rock beer and a Marlboro—back in the days when I considered both treats the only multivitamins a growing girl could need—my brilliant college roommate, Olivia, told me that “entropy is what gives time its arrow.” I took a long swig of the Rock that Rolls and followed it (for good measure) with a slow drag of my cig. “Yes! Exactly!” I enthused. Of course, I didn’t understand one whit of what she was saying. Time’s arrow?? I sort of knew about entropy from high school physics. Entropy had to do with disorder and chaos, and with the general fact that it takes work to tidy things up. A half hour after mopping the floor, it will be dirty again. I was also pretty sure that entropy can explain why a dropped slice of bread and butter will always land butter-side down.

With a couple of decades of meditation under my belt, I think I understand Olivia better now. Existence is all flux and change, and from the broadest vantage point, the swirl of atoms that we call our world is just dynamic energy: ceaseless interchange and exchange. Nothing is ever truly new, and nothing is ever truly lost. This is what Asian philosophies and traditions mean when they describe the universe as beginningless and endless. It’s all one continuing swirl.

But from the vantage point of an individual, things most decidedly do begin and end. At this moment, from my seat at a taverna on an Ikarian hillside, I am taking delight in watching a tethered mama goat enjoy the sun and tender spring grass. Her kid pulls at a teat for a moment, then skips away. As I watch the mama goat’s little sprig of a tail swishing back and forth to shake off flies, I suddenly realize that this restaurant serves goat, and this adorable kid is no doubt just a few short weeks away from being on the menu. From the highest vantage point, grass, goat, flies, and taverna dinner are all one unceasing cycle of life. But from the kid’s vantage point… As a friend of mine facing his own mortality once said, “That ratchet only goes one way.” That’s time’s arrow. Our lives move from now toward later. From our vantage point, the ceaseless flux of existence ratchets in one direction only.

Time brings beginnings and endings of all sorts—some joyous, some heartbreaking.35 In the midst of these joys and heartbreaks, time’s arrow also provides us with a potentially life-changing gift. Over time, things settle. Water flows from the highest point to the lowest, then pools and collects. The joints and sills of a new house settle into the earth. The frictions and frissons of cohabitation settle into the intimacies of domestic life. And when we sit still for a while, laying down our digital tech and our daily tasks, the swirling brew of our heart and mind also begins to settle. Over time, as we meditate, our breath begins to drop into our belly.

In his poem “I Go Among Trees,” Wendell Berry describes this settling beautifully:

I go among trees and sit still.

All my stirring becomes quiet

around me like circles on water.

My tasks lie in their places

where I left them, asleep like cattle.

Mindful meditation is where the unceasing swirl of existence meets the arrow of time. This sounds rather grand and exotic, but it’s actually as simple a reality as a glass snow globe. Have you ever seen one of those? You can buy cheap plastic versions of these in any souvenir shop, but the best kinds are the old-fashioned ones. The iconic snow globe is a hollow sphere of glass, filled with water and plastic “snow” particles, settled into a wooden base with a little scene—maybe Santa at the North Pole, or a dreamy little cabin with a chimney.

We’re all like snow globes. All day long we’re shaken up by activity, thought, emotion. The world shakes us up, our past habits shake us up, our present thoughts and feelings all shake us up. The snow swirls around. The scene inside is obscured. It’s impossible to know what to make of the entirety of our experience. What we encounter, in our mundane and habitual state of agitation, is just the swirl.

And then, perhaps, a moment of mindful stillness arises. We sit ourselves down without movement or goal. Our tasks, as the poet says, lie in their places, asleep like cattle. To paraphrase Jon Kabat-Zinn, we decide to pay attention, on purpose and without judgment, to life just as it is right now. We set the snow globe down on a table or a mantel, and slowly, gradually over time, the snow begins to settle. Our own busy body, mind, and heart begin to settle.

First, the swirling cloud of snow slows down. Individual flakes become distinct.

Then the scene begins to emerge.

The snow-globe sky begins to clear. The light shines through.

Meditation practice is like that. As we mindfully drop anchor and slow down, settling into an awareness of our breath or of our body at rest in our chair, we might only at first make out a dim and messy swirl. The activity of our mind and heart might just be one big blur. But bit by bit, the individual flakes of our thoughts, feelings, and sensations become more vivid and distinct. And as we further sit, in any given meditation session or over a number of sessions as our practice deepens, everything slows and settles.

Would you care to join me right now for ten minutes of settling in?

Check out the “Snow Globe Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Check out the “Snow Globe Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

From Settler to Seeker

If the four suits map the settled and peaceful heart, the cards of the so-called “Major” Arcana—also known as the trumps or trump cards—map instead a holy restlessness, a pilgrimage. From its earliest inception during the Italian Renaissance, the imagery of the trumps has been designed to call forth the distinct stages in the life of a seeker. From the overt Christian allegories of the original historical decks to the variety of images on modern decks, these 22 cards paint a recognizable sequence of journey and discovery.

Now, Tarot historians will patiently remind us that the Tarot deck was invented as a game—not as an oracle or a spiritual tool. The history of Tarot is part and parcel, in fact, of the history of playing cards. Playing cards were introduced in Europe in the 1300s, probably entering the continent via Muslim Spain. Then, as now, the regular playing card pack consisted of four suits with minimally illustrated number cards (i.e., pip cards or pips) ranging from Ace to Ten, along with a series of court cards for each suit. The gambling and trick-taking games that utilized these early card decks followed relatively straightforward rules. In general, higher numbers or more highly ranked figures such as the King or Knight beat lower numbers. However, about fifty years after these first decks appeared in Europe, fifteenth-century Italian artists and players introduced a new fifth “suit” of 22 cards called the trionfi, or triumphs. 36

These modified trionfi decks operated according to somewhat different rules. If you’ve ever played a game like Hearts or Bridge, you’ll understand immediately what the trionfi enabled: namely, a way to take a trick of cards without following suit. The “triumph” cards were invented in order to “trump” (the word comes from triumph) the ranking of the pips and court cards. Indeed, the fifteenth-century Tarot deck invented the whole idea of trumps in game play.37 In an important sense, Tarot is the basis for games such as Bridge—and Tarot gives the English language the very word for any object, person, or action that automatically prevails over all else. We’d have no puns on the name of the forty-fifth president of the US without the history of Tarot. It’s because of Tarot that we can say things like “love trumps hate.”

Originally unnumbered and unlabeled, these special trionfi cards included rich allegorical images: images of a vagabond, a mountebank, an Emperor, a Pope, a Devil, Death, etc. In game play, the value and meaning of these cards was determined not by numerical ranking—for they had no numbers or ranks—but instead by the “divine comedy” to which they alluded. Each image, each card, indicated a successive moment in the unfolding pageant of human salvation. The cards were called triumphs because they illustrated human life as a triumphant spiritual progression: each card depicted a separate stage in this process, a victory won on the path to salvation—a new “triumph” on the road to heaven.

This notion of victory harkened back to the tradition of ancient Roman victory parades (also called triumphi in Latin), where a conquering general returned from battle to parade his troops, his spoils, and his captives down the streets of Rome.38 These Roman triumphs have inspired centuries of military, religious, and political spectacles. It’s because of the Roman tradition that we have an Arc de Triomphe in Paris, built to commemorate Napoleon’s 1806 victory at Austerlitz. But Napoleon wasn’t the first latter-day ruler to imitate the triumphal imagery of imperial Rome. That honor apparently goes to Frederick II of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, who in 1237 staged a triumph in Rome to commemorate his victory over the city-state of Milan. In late medieval and early modern Europe, the iconography of the Roman triumph became a common way for rulers to celebrate their power.

About a century after Frederick, not long before the first Tarot decks appeared in Italian court life, this iconography also made its way into literature in what would become one of the most popular and most imitated poems of the Renaissance: I Trionfi (The Triumphs) of Petrarch (1374). Petrarch’s poem takes the imagery of the conquering hero and ties it to an allegory of redemption. The poem is a dream vision in which the poet, languishing in unrequited love for his beloved Laura, sees six interlocked visions of triumphal parades. The parades begin with the Triumph of Love, where the god of love displays his countless victories over warriors, gods, emperors, kings, biblical figures, etc., leading captives who include Antony and Cleopatra, Mars and Venus, Samson and Delilah. … and Petrarch, the poet himself.

From there, the poet moves to the Triumph of Chastity, where Petrarch’s beloved Laura is herself the conquering hero over Love (because a chaste heart proves stronger than the ardor of passion). From Chastity, the poem advances to the Triumph of Death. Death is the great leveler, who can overpower even the purest and most noble of souls, including chaste Laura. But in his turn, Death is conquered by Fame. The Triumph of Fame teaches us that our deeds can outlive us, just as Petrarch’s writings about beautiful Laura have preserved her memory for eight centuries now. However, Fame cannot prevail forever. The next triumph belongs to Time. Even the most famous of heroes and deeds are ultimately buried by the dust of centuries.

The sixth and final triumph, the Triumph of Triumphs, is the Triumph of Eternity. Petrarch writes:

When I had seen that nothing under heaven

Is firm and stable, in dismay I turned

To my heart, and asked: “Wherein hast thou thy trust?”

“In the Lord,” the answer came, “Who keepeth ever

His covenant with one who trusts in Him.

In what can we place our trust? Each step of the way, we are chastened by the impermanence of human existence. But each step also takes us one rung closer to the final victory: the triumph of the faithful, who put their trust in God. In essence, in his Trionfi, Petrarch creates a literary turducken (i.e., that poultry dish where a chicken is cooked inside a duck that is cooked inside a turkey—yum!). Each conquering hero—Love, Chastity, Death, Fame, Time, Eternity—subsumes what has come before, until finally the winner, Christ, takes all. As literary historian Robert Coogan puts it, “Petrarch reflects all the variety of life and still unifies his pageant by the inexorable movement toward Eternity’s triumph.” 39 Petrarch’s poem manages to address the full range of human life while still circumscribing it within the story of Christian salvation.

It’s been over sixty years now since art historian Gertrude Moakley argued that Petrarch’s poem is the source of the imagery in the Tarot trumps.40 Few now would agree unequivocally with her claims. Petrarch’s six triumphs do not neatly map onto the succession of 22 cards. Most significantly, not a single of the Tarot trumps celebrates Chastity, who plays such a central role in Petrarch’s account. Nonetheless, it’s thanks to Petrarch that the idea of “triumph” gets tied to the story of spiritual awakening. His poem is a conversion poem. In the final triumph, the seeker realizes that what he has been pursuing all along lies with the one truth in heaven. In a way that decisively changes the history of playing cards, Petrarch marries the imagery of conquest to an allegory of the seeking heart.

Thanks to Petrarch, then, with the earliest Tarot decks we find the allegory of Christian redemption unfolding via a succession of 22 interlocking triumphs. All of the existing fifteenth-century decks use the same set of images, and although there seem to be some regional variations in ordering, consistent groupings of the cards always appear together, allowing us to discern the same three-stage path from folly to wisdom. Tarot artist and scholar Robert M. Place describes these three stages like this: “The first group [of cards] is concerned with worldly power and sensuality; the second group depicts time, death, and the harsh realities of life along with the virtues; and the third group depicts a mystical ascent through celestial bodies of increasing radiance.” 41 The succession of these carte da trionfi, these “triumph cards,” is predictable and generic and would have been immediately recognizable to any early modern game player. Indeed, that generic predictability was essential for the game to be played: the value of each card has to be immediately obvious and apparent in play.

In contrast, for us modern Tarot readers, the imagery of the trumps is rather opaque. Most of us haven’t been schooled from our early days in catechism and redemption history. For most of us, the allegories of sin and salvation are unfamiliar. We didn’t grow up with the likes of Petrarch or Dante. Instead, we moderns tend to turn to psychology and to the transpersonal depths of archetype.

Most influentially, modern Tarot readers have interpreted the 22 trumps through Jungian psychology, especially as understood in terms of what mythologist Joseph Campbell calls the hero’s journey: an archetypal narrative pattern that we find repeated again and again throughout world cultures. The hero is called to adventure (a call she often resists until a mentor leads the way), then enters into a realm of fantastic wonders where she is tried and tested and is ultimately triumphant. She may initially resist returning to the world of the everyday, but return she must to save the lives of others. We can find this pattern of departure, initiation, victory, and liberation in everything from high to low culture, from the Church to the cineplex. We see it in the lives of deities, prophets, and saints, in the stories of vigilantes and superheroes. We see it in the stories of Socrates, Siddhartha, Jesus, Jonas, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Mad Max, Luke Skywalker, Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, Arya Stark, Diana Prince, and Black Panther. The list of journeying heroes is endless.

Ultimately the hero’s journey is a story of awakening. It is the story of the seeker—a one-size-fits-most story that suits Christian redemption allegory as well as the latest Marvel adventure. As Robert M. Place skillfully points out, in its essence the hero’s journey recounts our universal quest for the highest good, namely, “a mystical transformation that awakens one to the truth of spiritual oneness and removes the psychic barriers that separate an individual from the entire creation.” 42

I resonate deeply with Place’s discussion. My own view of Tarot as a complete practice, as a practice aimed at integrity and integration, can also be articulated in his terms as “an awakening to oneness.” However, a pervasive dualism lies smack at the heart of this mystical philosophy. Ironically, this philosophy of oneness is founded upon a fundamental duality. The mystical path seeks unity, but it begins with a divided universe. This division finds expression in many forms, but first and foremost it is the duality we’ve already seen in Petrarch’s Trionfi. I’m speaking here of the division between eternity and time. In his poem about awakening, Petrarch ultimately learns that “nothing under heaven is firm and stable.” Everything on earth will fade and die. Indeed, the only stability lies in the eternal realm we call heaven.

This dualism between heaven and earth, eternity and time, decisively cleaves the material world from the world of truth and wisdom. In a Christian or monotheistic context, the split between eternity and time is the split between the Creator and his creation. The triumph of eternity reconciles this divide—but it does so at the expense of our mortal bodies and our human frame of time. As Petrarch writes in his vision of eternal redemption: “No more will time be broken into bits, / No summer now, no winter: all will be / As one, time dead.” Eternity kills time. Eternity brings us a oneness that pulls everything together—but in the process of this triumphal unification, what gets left behind are precisely all the precious, individual bits of a given life: summer, winter, time itself. Summer, winter, time itself. The physical, earthly, temporal, and “merely” human qualities of existence must be disavowed so that spirit may find its freedom.

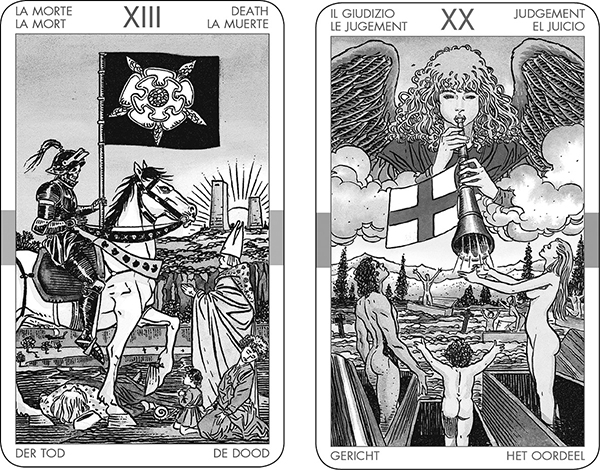

Time vs. eternity. Flesh vs. spirit. This dualism defines the Tarot’s triumphal logic, and nowhere do we see it more clearly than in the juxtaposition of Trump XIII (Death) and Trump XX (Judgment).43 The three figures succumbing to the Triumph of Death in the earlier card (king, child, and maiden) have now been restored by the Triumph of the Last Judgment. They stand renewed and reborn. The mortal flesh, once subject to death’s blows, has now been resurrected into eternal and changeless forms. (And apparently getting resurrected leaves you with ripped biceps, fabulous glutes, and gorgeous hair!) Left behind are all the accoutrements of a human life, the trappings of power, of family, of station and class. In their place, we find just the open, empty, blank stare of the grave.

This triumphal logic is a far cry from where we started in this chapter, on the hillside with the mama goat and her kid. There I suggested that we simply cannot choose between the world of time, birth, death, etc., and the world of eternal stillness. Indeed, I proposed that stillness itself is a stance we find in the middle of life’s ups and downs. I suggested that mindfulness practice is what happens when the vast oneness of life meets the one-way arrow of time. Mindfulness is what happens when the seeker meets the settler: when the path to awakening incorporates a fully embodied life.

Death (XIII) and Judgment (XX): Triumphs of Death and Judgment

Another way to make the very same point: mindfulness proposes a thoroughly nondual approach to the world. With mindfulness practice, we aim to encounter a world not where eternity triumphs over time, but instead where time and eternity are two sides of the very same existence.

So if the trumps are dualistic and mindfulness is nondualistic, can we ever build a Mindful Tarot approach to the trumps?

I’m so glad you asked. Why, yes, we can!

Our mindful approach to the trumps relies on the one trump who really isn’t a trump at all: the Fool.

The Zero

The Fool is extraordinary, literally. He stands outside the ordinary scope of things. Technically, the Fool is not a trump at all but falls out of the sequence as the “Excuse”: a card that releases players from either following suit or playing a trump.

The Fool’s extra-ordinary status was celebrated in one of the earliest Tarot decks, the 1491 Sola-Busca. We don’t know anything definitive about its origins, but in its overall design, the Sola-Busca may have been conceived by Ludovico Lazzarelli (1447–1500). Lazzarelli was a humanist and a poet who, like Petrarch a century earlier, sought to reconcile Roman, Christian, and mystical traditions.

The Sola-Busca is noteworthy for a number of reasons. It is, in the first place, the oldest Tarot deck surviving in its entirety. All 78 cards exist and can easily be viewed in modern reproductions. Indeed, Pamela Colman Smith, the artist of the historic 1909 Waite-Smith Tarot deck, almost certainly viewed copies of the cards in the British Museum, where a complete set of photos was available. We can see the Sola-Busca’s influence most directly in the Waite-Smith Three of Swords, Ten of Wands, and Queen of Cups. The Sola-Busca is also the oldest surviving printed Tarot: its images were produced via the art of intaglio copper engraving. It is furthermore the oldest deck with fully illustrated pip cards. It was not until the grand occult syntheses of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that we would again find an effort to bring iconographic detail to the pips.

For our purposes, however, what is most remarkable about the Sola-Busca is its Fool. The Sola-Busca provides the first image of Il Matto, of the crazy or foolish one, to be numbered zero. Moreover, the entire Sola-Busca deck is numbered and incorporates an oddity that we sometimes find in modern decks as well: the trump cards all have Roman numerals (I, II, III, IIII, V, etc.), while the Fool and the four suits are given Hindu-Arabic numerals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.).

This juxtaposition of these two numbering systems, Hindu-Arabic and Roman, echoes the Sola-Busca’s historical moment: in the late fifteenth century, Europe was just coming to terms with the use of the zero. Roman numerals lack a zero, but the digit is essential to the Hindu-Arabic system.

Hindu-Arabic numerals entered Europe through Muslim Spain in the 1200s, but didn’t begin to displace the cumbersome system of Roman numerals until the 1400s, the same century in which the Tarot was invented. Europe was suspicious of the new Hindu-Arabic numerals. In fact, in 1299 Hindu-Arabic numerals were outlawed in Florence, ostensibly because they enabled easy forgeries. If you’re tabulating your goods and earnings, it’s far easier to turn “50” into “5000” than to turn “L” into “MMMMM.” The introduction of the zero as part of this number system nonetheless marked a huge and tumultuous advance for Europe, enabling such diverse phenomena as the vanishing point in perspective painting, double-entry bookkeeping, and the rise of modern science.

But the zero digit was a terrifying oddity. Numbers help us count, add, subtract, multiply. They point to the world of things. Why have a digit—a word that literally means finger—if you’re not going to point to some thing? What is this digit that points to nothing, no thing? Even more startling is the fact that zero counts nothing and yet magically adds substance to all other figures. The numeral 4 becomes 40 or even 400, 4000, 40000, ad infinitum. A little nothing bends us toward infinity. And thanks to zero, which itself counts nothing, the same nine numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) can count everything that can ever be counted. As the placeholder that enables the decimal system underlying all of modern mathematics, finance, and science, zero enables the endless expansion of numbers. Even though zero brings nothing to the party, it can feed everyone there. The concept of zero did not exist in the classical mathematics of the Greeks and the Romans, and it was an abomination at first in the Christian West. What use did a good Christian have for nothingness? God created something, not nothing.

Indeed, the concept of zero arose from the non-Christian world—from the Hindu notion of the void, or shunya (the word becomes the Sanskrit term for the mathematical zero): an emptiness that simultaneously holds the potential for everything. One ancient Indian text spells out the mathematical ramifications of this idea: “Just as emptiness of space is a necessary condition for the appearance of any object, the number zero being no number at all is the condition for the existence of all numbers.” 44

The zero ties together emptiness and infinity, nothingness and everything. No wonder Europe was nervous about the zero. The Christian West likes to keep nothingness on the side of Death, the great leveler with his mighty scythe, cutting away all that is (see Death card detail). Everything, in contrast, belongs with God on the side of eternity (see Judgment card detail). Zero upsets that neat dualistic balance. Emptiness and infinity, nothingness and everything, instead become two sides of the same hollow coin.

Death with his scythe in Trump XIII of the Marseille Tarot— from everything to nothing

Judgment with the trumpet of resurrection— from nothing to everything

Back to the Sola-Busca: In the very midst of Europe’s encounter with the zero, we find a deck of cards that identifies the Fool with this transgressive new concept. Moreover, Lazzarelli’s deck underscores both the “Roman-ness” of the trumps and the foreignness of the Fool. As we’ve seen, Tarot trumps derive their logic and meaning from the tradition of ancient Roman triumphs: the parades that celebrated military victory. With Lazzarelli’s deck, it’s almost as if that triumphal logic is being disrupted by this interloping Fool. The Hindu-

Arabic zero of the Fool contrasts with the Roman numerals on the remaining 21 cards. In addition, the figures on Lazzarelli’s trumps are all clothed in Roman battle gear, while the Fool appears to be a Celt, bagpipe in hand and cloak fastened at the shoulder. Furthermore, the majority of the cards seem to reference periods of conflict within, and ultimately the downfall of, the Roman Republic. These trumps are not so triumphant! Maybe that savage half-dressed Celt, and not the civilized Roman hero, will have the last laugh. After all, that crazy fool with his bagpipe manages to turn an empty bladder of wind into music!

Some three hundred years after the Sola-Busca was printed, the father of the occult Tarot, the French author Antoine Court de Gébelin, first articulated the all-and-nothing logic of the Fool:

As for this Atout [i.e., Trump], we call it Zero, although it is placed in the game after XXI, because it does not count when it is alone, and has only that value which it gives to others—just like our zero: thus showing that nothing exists without its folly.45

De Gébelin is referencing the role of the Fool in game play. In the sequence of the trionfi cards, the Fool is a complete anomaly. It cannot win tricks, cannot trump any card. It merely excuses the holder from play and at the end of the trick gets scooped back into their hand. No one can win a game of Tarot just by playing the Fool. But at the end of the game, when points are being tallied, the Fool’s value is as great as the highest trump. Like the zero digit, the Fool is all and nothing.

The Tarot was unknown in Paris when de Gébelin wrote his account. And while nearly all of his assertions about the Tarot’s mystical origins were false (albeit decisively influential for later occult writers), his discussion of the Fool was uncannily precise. According to de Gébelin, the Fool shows us that nothing exists without its folly. Indeed, the Fool is our invitation to explore the emptiness—the folly, the blindness, the mystery, the lack of finality and substance, the interconnected open-endedness—at the center of each moment. One of the great twentieth-century Zen masters, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, had a name for this sort of folly: beginner’s mind. In his book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Suzuki writes, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.”

A life of beginner’s mind. A life of many possibilities. Such is the fundamental journey of the Fool. The Fool’s work is never completed. Her path is ongoing. Can we meet the many possibilities inherent in each moment? Can we meet the all and nothing with which life patiently and repeatedly presents us?

Our work with the trumps will be to bring the Fool to each and every one of them: to see an open zero, both egg and grave, in each and every card.

35. Back to last chapter’s Fourth Abode: carving open this truth, the truth of our impermanence, is perhaps the ultimate task of the Swords.

36. The decks also apparently introduced a fourth, female court card: the Queen, positioned between the Knight and the King. I discuss this point in part 2.

37. Michael Dummett points out that the idea of trumps might have been invented in Germany slightly earlier than when the Tarot emerged in Italy. Nonetheless, it was the Italian Tarot pack—not the German game—that influenced the subsequent history of playing cards. See Dummett’s article “Tarot Triumphant,” FMR, 48.

38. Tarot artist and scholar Robert M. Place has offered a persuasive discussion of these ancient triumphs as essentially “ritual reenactments” of what mythologist Joseph Campbell called the hero’s journey. (See my discussion of Campbell later in this chapter.) See Place’s book The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination, 108–111.

39. Coogan, “Petrarch’s ‘Trionfi’ and the English Renaissance,” Studies in Philology, 306–327.

40. Moakley first argued this point in “The Tarot Trumps and Petrarch’s Trionfi: Some Suggestions on their Relationship” in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library (v. 60, 1956). See also her 1966 book The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family: An Iconographic and Historical Study.

41. Place, The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination, 93.

42. Place, The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination, 51.

43. For the name of Trump XX, I follow American usage throughout this book, even though the Universal Tarot uses the accepted British variant, like the Waite-Smith itself.

44. Cited in George Gheverghese Joseph, The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics, 345. I am also indebted to Dr. Elizabeth P. den Boer for sharing with me her recent unpublished text, The Origin of the Zero Digit and the Concept of Śūnya. She writes: “Whereas all other signs refer to concrete presence or aspects of duality, zero may be said to act as tangible reference to the intangible or the nondual realm.”

45. Court de Gébelin, Le monde primitif, 368.