The Daily PULL:

Pausing, Unknowing,

Looking, Leaning In

Mindful Tarot is about finding, and living, our questions.

To start this sort of practice is to embark on a fool’s journey. As I suggested in the last chapter, that journey requires beginner’s mind: an absolutely alive, embodied, and open freshness. The freshness of the very first card in the Tarot deck: the Fool. What could be more delicious?

I once heard a Zen teacher refer to beginner’s mind as the feeling of what’s that? It’s like sticking your hand in your pocket and feeling a small object—maybe rough or smooth, dense or light—and not knowing what you’ve touched. Can we linger in the openness of that moment of contact, when the object isn’t yet “key” or “penny” or “forgotten cough drop”? And then, can we engage every ounce and speck of our curiosity, allowing ourselves to fall in love with the toothy sharpness of the key, with the tangy smoothness of a penny, with the waxy crinkle of a cough drop wrapper?

What’s that?

This is a practice of patience. “Have patience,” the poet Rainer Maria Rilke counseled a young protégé over a century ago in Letters to a Young Poet. “Try to love the questions as if they were locked rooms. … Live everything. Live the questions now.” Mindful Tarot cultivates our capacity to live and love what is unknown and unresolved; to live, like the Fool, in the openness of beginner’s mind, inhabiting what hasn’t yet been decided, processed, and packaged. That openness, that space of the question, is nothing less than the tender growing edge of our lives. It’s nothing less than the present moment: complete, lavish, and unconstrained.

In this chapter, we’ll explore the kind of patience required for a Mindful Tarot practice. It’s not as complicated or onerous as you might think! We can practice Tarot mindfully with any spread and any deck that we choose. As when building any other spiritual practice, it’s important to start out simply and with consistency. For me that means choosing a straightforward, unassuming spread and whatever deck happens to be handy—and then to commit to a daily pull of cards. Commitment and simplicity are key. Otherwise we run the risk of continually trying to leverage the experience, ever seeking the greener grass over yonder. If we’re not careful, our own restless energy and yearning for answers will provide no end of distractions.

So—grab a deck, any deck. Really! Any deck! The invitation here is to let go of the worry that your deck has to be particularly “special” or “deep.” Just grab whatever you’ve got. And as for grabbing, a note about shuffling: With Mindful Tarot our aim is to let go of our restlessness and our efforts to leverage the world. We’re not trying to be intuitive with our shuffle nor aiming to feel particularly energized or guided. We don’t need any extra-special mystical powers or insights to get us going. To gear up a daily Mindful Tarot practice, we don’t need to acquire anything special at all. We don’t need a magical message or buzz from the deck, and we don’t need to impart a mystical charge to the deck. Life itself, in its abundance and specificity, will provide all the magic and mystique we need.

We’ll keep it as simple and straightforward as we can. Just shuffle the deck so the cards are in random order. (I find it helpful to have a particular way I shuffle, every time I shuffle, so that I completely avoid the impulse to make the moment esoteric and “deep.”)

Okay?

Do you have your deck?

Take the deck out of its box, bag, wrapper, or drawer, and simply lay it on the table in front of you. Hello, 78!

Let’s leap in! In this chapter, I’ll use my three-card Chariot spread to explore the fundamental steps of a daily Mindful Tarot practice: what I call the Daily PULL. (You can find more information about the Chariot spread at the end of this chapter.)

Pausing

In the context of Tarot, the word pull can be both a verb and a noun. As a verb, pull refers to the act of randomly selecting cards. It’s a synonym for draw or deal. I pull Tarot cards in order to read them. As a noun, a pull is the spread or layout of cards that I interpret.

PULL is also the central acronym for Mindful Tarot. It describes a four-step process of self-compassionate, patient inquiry into the richness of our lives:

Pausing–Unknowing–Looking–Leaning in

It all begins with the power of the pause.

So … Stop it. Really. Please. Just stop.

For twenty minutes every day, stop what you’re doing—so that you can start up the special bit of nothing that is spiritual practice.

Just hit pause.

A daily Mindful Tarot practice begins with setting aside a time for daily practice. It sounds obvious, but this step can be daunting and can put the kibosh on a spiritual practice before it ever gets off the ground. So right now, dear reader, I invite you to decide on a time for your daily practice. When are you going to hit the pause button in the middle of your daily routine? What do you think? For many people, mornings are best. Carving out twenty minutes at the beginning of the day can set the tone for everything that follows. Centuries upon centuries of seekers have taken this route.

Believe me, I know that the morning already feels rushed. There’s already not enough time, right? But I challenge you to be curious about that judgment. Here are some alternative ideas: Why not wake up earlier? Forgo that second cup of coffee? Take your shower the night before? Lay out your next day’s clothes before you go to bed? Ditto with making your lunch, your kid’s lunch, your spouse’s lunch, your dog’s lunch … If waking up early is hard for you, the night before can offer a lovely expanse of time. You can use it for all sorts of things that normally make the morning a mad rush.

Or why not vow not to check email, newsfeeds, Facebook, etc., before 9:00 a.m.? (You’ll thank me later if you choose that route now.)

Twenty minutes. Give yourself that.

And then, turn off and put away your cell phone and any other distracting devices—Fitbit, mp3 player, iPad, computer—that might go beep or bop or tempt you with their luscious screens. If you can, shut a door, leaving critters, family, friends, and roommates on the other side. Take both time and space for yourself. Take a timeout.

Taking time out is, indeed, the single most important thing you can do for yourself, for your friends and family, for your frenemies and the strangers in the world, and for the planet itself. In fact, carefully structured stopping is the core not only of mindfulness practice but of any path of awakening. The Psalms of the Hebrew Bible imagine the Almighty’s own advice to us: “Be still, and know that I am God” (Psalm 46:10). When we quit squirming, the universe tends to fill the gap. All the creatures of the forest return to their business: birds pecking at the ground, deer grazing on the tender shoots of plants, squirrels clambering up the trees. When we learn to pause, we give the whole world around us an opportunity to come forward, breathe, and unwind.

So hit the pause button on a regular basis and put your daily routine on hold. Your tasks will lie quietly waiting for your return. Your day won’t even miss you. In fact, your day will be the better for it.

When we hit the pause button for our spiritual work, we’re actually practicing a general skill that we can bring into daily life. There’s a quote, often attributed to the extraordinary psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, that comes to mind:

Between stimulus and response there is a space.

In that space is our power to choose our response.

In our response lies our growth and our freedom.46

Our lives are largely ruled by reactivity, like a game of tennis. A ball comes at us and we swing. Thwock! We connect or we don’t, but the ball remains in play no matter what. A volley here and a volley there. Sometimes our stroke lands true, and we rejoice. Sometimes we pick up the ball ourselves, take the initiative, and serve. But no matter what, we’re caught up in the ongoing action, our movements always in reaction to what comes before, the pace of our lives seemingly beyond our control. Thwock, thwock, thwock.

Stimulus and response are not the same thing. The ball hurtling toward us and the swing of our racket are two separate things. Unfortunately, life usually moves too fast for us to notice this separation. We just keep swinging, as if the game itself were inevitable. Or rather, it’s not necessarily that life is too fast; it’s more that we’re simply caught up in the flow. It’s not that we can’t notice the gap between stimulus and response; it’s just that we don’t notice it. Habitually we just keep swinging. Thwock, thwock.

Mindfulness practice begins with the pause. We stop in the middle of our daily routine and take time out for structured spiritual practice. And then, bit by bit, we learn to notice that we can pause at any point in the very midst of life. We can notice our triggers and our reactions, and we can be curious about that particular volley. Over time, as we get better and better at pausing, and the gap between stimulus and response may very well widen. Over time, we may indeed learn to rest in that space of freedom.

Over time, as we practice the power of the pause, we may even begin to exercise the power of choice.

Check out the “Pause Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Check out the “Pause Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Mindful Tarot Step 1: Pausing

I’m sitting in a comfortable upright position in front of a small table. My Tarot deck, the Universal Tarot by Roberto de Angelis, sits facedown in a neat stack in front of me. My journal and pen are at my side. I’ll need them for steps 3 and 4. In step 4 I may also want to consult some card meanings as I “lean in” to the spread. I have a few guidebooks near at hand—but far enough away that they don’t become a distraction or a source of discouragement. I don’t need to rely on the interpretations of others. Mindful Tarot is about me and my experience. I have all the expertise that I need.

I’m in a part of the house that feels quiet and peaceful. My cell phone is in another room, and my dogs are outside, on a walk with my husband. There’s just me, my chair, my table, my deck, my journal, and my beloved thirty-dollar Timex wristwatch, with its easy alarm function. I’ll want to use a timer for portions of this practice (in steps 3 and 4).

Closing my eyes, I take three slow and deep breaths. As I breathe in, I feel my ribcage expand and my body lift up toward the ceiling. I can feel a rising and a sense of fullness in my upper back, shoulders, and neck. At the top of the breath, I pause slightly, feeling a tug just below my sternum. And then, releasing the breath slowly all the way down to the base of my lungs, I can feel my torso relax, my shoulders and upper back settling downward, and all the long muscles of my arms and legs softening into the chair. I feel the pull of gravity in my hips and buttocks as my weight sinks into the earth.

After three of these slow and conscious breaths, I pick up my deck and begin to shuffle. My shuffling follows a set pattern, one I use every day. I do what I like—what feels best for my hands. The pattern I’ve chosen doesn’t matter in and of itself, but the consistency does. Consistency keeps me grounded and honest—keeps me from seeking esoteric depth or mystical guidance—and helps me simply remain in the here and now.

I like the riffle shuffle, where the cards are interleaved together by pulling upward on each half of the deck with the thumbs and then dovetailing the cards by releasing the thumbs. I also like the overhand shuffle, where cards are gradually shifted from one hand to the other in small packets. Because I like both, I do both: I riffle shuffle and overhand shuffle the deck three times, then finish off with one last overhand. If I’m working with a brand-new deck, I go through this whole process three times. Nothing special here. I shuffle like this because it works well for my hands and I like the number three—a number of synthesis and growth.

Shuffling is itself a deeply embodied practice. As I shuffle, I’m aware of the texture and colors of the cards, of the movement of my hands, of the sounds of sliding and riffling cardboard.

I finish shuffling and reposition the deck in front of me, facedown. I rest my hand on it, feeling the sweet and smooth solidity of the stack.

I am not thinking about a question. My mind is doing whatever my mind usually does. That’s just fine, of course. Throughout this Mindful Tarot practice, whenever I notice myself drifting elsewhere—daydreaming about something or worrying about a task or even starting to fixate on a particular question or concern—I acknowledge what I’ve noticed and bring my attention back to the embodied activity at hand.

For now, that’s just me breathing here, my hand gently resting on a pile of rectangular cardboard forms.

Unknowing

Pausing cleanses the palate, refreshes the screen. Now the choice is ours. Are we just going to leap back into our regularly scheduled programming, already in progress? Or are we going to take advantage of this brief moment of blankness to turn toward our experience with a big question mark? An anonymous fourteenth-century English mystic called this sort of conscious, cultivated blankness an effort to pierce the “cloud of unknowing.” 47 Can we “unknow” our experience?

In the Unknowing step of Mindful Tarot, I lay my cards out into my chosen spread and aim to encounter them with all the freshness I can muster. I aim to encounter the cards as if I were looking into an empty mirror.

The task of unknowing is not for the faint-hearted! There’s so much we already know, or at least seem to have already decided, about our experiences. Even for those who are brand-new to Tarot, the imagery of the deck and the numbers and words on the cards are all bound to bring up rich associations. How can it be possible to “unknow” all of this?

There’s a wonderful Japanese Buddhist word for our perceiving mind: nen. Nen literally means something like mind-moment: the contents of our mind and heart right now, in the experience of this very moment.

According to traditional Zen psychology, our conscious experiences always involve three basic mind-moments. Each conscious experience entails a first, a second, and a third nen. The three nen build on each other, like three layers of a wedding cake.

Take, for example, the phenomenon of a tree falling in a forest. In the first, foundational nen, we encounter that phenomenon as bare sensation, our nervous system responding to raw sensory data. A tree falls in a forest, sound waves reverberate in the cochlea of our ears, and the auditory nerve sends a signal to the brain. Kee-rash!

The second nen activates other parts of the brain, e.g., memory, language, spatial, and temporal intuition. A concept is born. An object is perceived. Falling tree.

In the third nen, we move into the realm of the subject. “I” am the person perceiving the falling tree, and I perhaps have all sorts of memories, judgments, and considerations about trees, about lumber, about forests. The third nen easily opens into a chain of story and judgment, likes and dislikes. This is where the floodgates open… Ah, I notice a tree falling down. Wow, another tree down! What’s happening to our old growth forests? Was the tree injured, or is someone just building a new garage for their fossil-fuel-burning behemoth? What’s happening to our planet? Why does no one care about the spotted owl anymore? And what about the rain forest, and global emissions? I just read that article about the exploitation of the Awá people. … Doesn’t anyone care what’s happening in Brazil????

The three mind-moments move faster than fast. No sooner has the tree fallen than we’re off and running to Brazil. A Zen teacher I know once defined a nen as 1⁄64th the duration of a finger snap! (One wonders how he measured the darn thing.) Our minds move so quickly from sensation to full-blown story that is it even possible to remain fresh and “unknowing” with regard to our experience? How can we forget what’s already, and so swiftly, rattling around in our heads?

Fortunately, we don’t need to forget a thing. Unknowing isn’t about erasing the memory banks or shutting down the neural synapses. It’s about a mindful act of imagination and will. Unknowing invites us to consciously bracket what we know—i.e., our concepts, judgments, feelings, and stories—and to tilt our heart toward our experience just as it is. The anonymous fourteenth-century English mystic explained this work as a two-step process of first covering or bracketing what we know with “a cloud of forgetting” and then beating “on that thick cloud of unknowing with a sharp dart of longing love.” 48 (Have you ever noticed just how sexy the language of mysticism can be? I want what she’s having!)

Bracketing what we know can be as simple as gently noting our feelings, thoughts, and judgments as they arise and then returning, as freshly as we can, to the flow of our present moment experience. For some mindfulness practitioners, this “noting practice” works best when we stick to general categories and inwardly name the movements of thought and emotion as they pass by. It’s like a catch-and-release program for fishing. We might grab hold of a flashy rainbow trout—e.g., a thought like Why does no one care about the spotted owl anymore?—and then simply note it in our mind: judgment or sad feeling. Once we have noted the mind-moment without getting caught up in the story of it, we can return simply to the sound of falling trees. Catch and release.

As for the sharp dart of love, the fourteenth-century English mystic encourages us to suspend thought by opening the heart. I reckon that we all have had an inkling of this “sharp dart” in those moments when someone we love suddenly enters the room. I remember a complicated trip I took to San Francisco. I was driving for eight hours, with the plan of meeting my then boyfriend in a cafe at a certain time. We’d been apart for months. Long before the arrival of cell phones and Wi-Fi, we’d arranged this meeting by landline. I arrived first, got my latte, climbed up to the balcony of the cafe, and settled in. An hour or so later, my boyfriend arrived. There he was! My heart leapt and was full. In that moment, I “knew” nothing—but the unknowing was the deepest intimacy I could then imagine.

It’s great to be twenty-five and in love! Fortunately, we can also simply practice this heart-opening through an ancient meditation exercise linked to the teaching of the Boundless Abodes.

Check out the “Noting Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Check out the “Noting Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Check out the “Heart-Opening Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Check out the “Heart-Opening Meditation” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Mindful Tarot Step 2: Unknowing

My hand still rests on the stack of cards. Still without formulating a question or a concern, I gently lift my hand and turn over the first card. I could use any spread. As with shuffling, the goal is simply to be consistent and simple. I use my Chariot spread because it is straightforward and also encourages me to grapple with the dualities and binaries that thread through the Tarot pack as a whole. This three-card spread echoes the structure of Trump VII (the Chariot) by flanking a central, governing card with two cards evoking complementary perspectives. (See the end of this chapter for a discussion of the spread.)

As I turn over my central card, I notice that it is reversed (i.e., upside down), but in Mindful Tarot, I don’t worry so much about reversed cards, so I turn it right-side up.

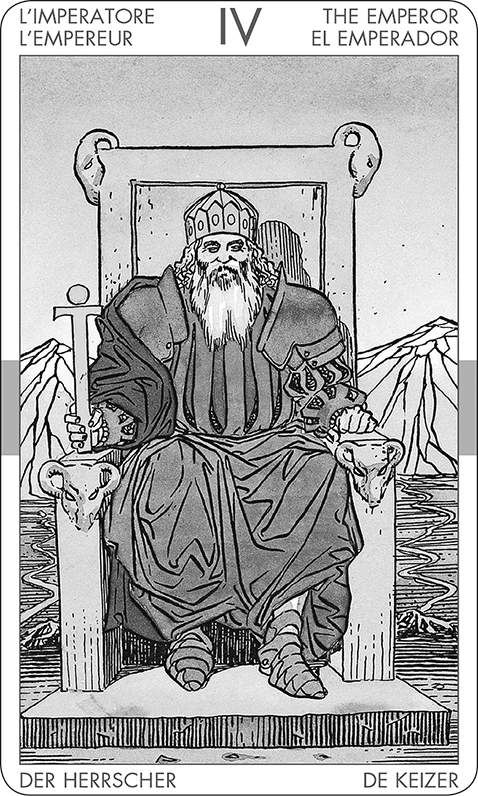

Instantly I recognize the figure, and a flood of associations rushes in. He’s the Emperor: this is me—my soul card 49 after all—and how perfect that I’d pick him as the centerpiece for my Mindful Tarot sample reading! He’s all about structure and building worlds, and I’m building the world of this book. But he’s the fourth trump, and that number four is always so tricky: four walls in a room provide shelter but may also hem me in. Can I ever liberate myself from my own preconceptions? My preconceptions are the walls of my “room”: they provide shelter but also restriction. Will I ever pierce the cloud of unknowing?

I take a deep breath, feeling my body expand to the sky and gently sink to the earth. I remember my “noting” meditation practice. Ah. Worried thoughts.

I return again to this figure. Looking into the card is like looking into a mirror. I try simply turning toward this image, this figure, like turning toward someone I love. He is me. Look at his teal booties! His teal pauldrons! The shape of his face and beard! There’s something sweet and genial here. Here’s a fellow I know. This is me.

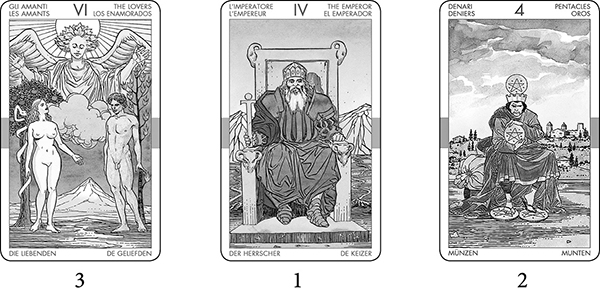

I turn over the next two cards—first the right one, then the left one. Like the white and black sphinxes in Trump VII, the Chariot, these two cards present two additional perspectives on my centerpiece.

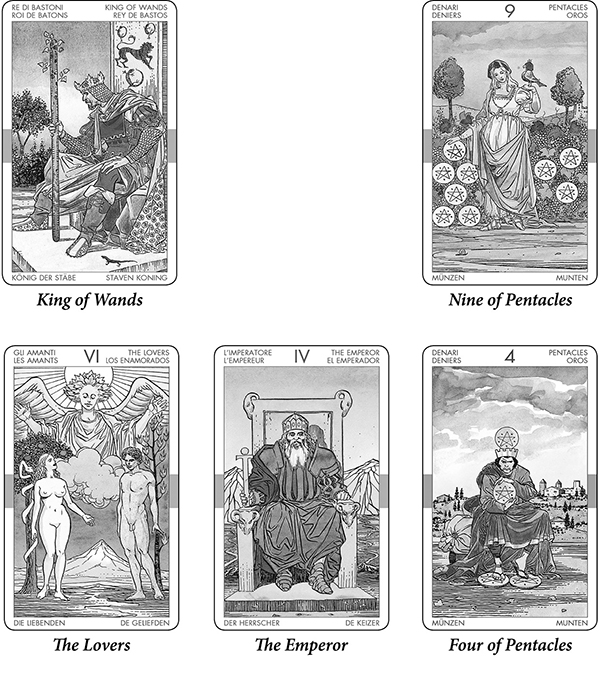

Again, instant recognition: the Lovers (Trump VI) on the left, in the position of the “bad” sphinx in the Chariot spread, and the Four of Pentacles on the right, in the position of the “good” sphinx. That seems reversed. The Lovers is a “good” card and the Four of Pentacles is a “bad” card. What’s going on? Is my spread broken? And here’s another four, like the Emperor: strong connection to the idea of stability—but also oppression and control.

I breathe in deep, taking note of the way judgment is leaping to the fore: Good cards, bad cards. Good sphinx, bad sphinx. Good stability, bad control.

Judging thoughts. I don’t have to hold on to all of these goods and bads!

I look back at the faces of these figures, leaning my body toward the table, physically inclining my heart toward the cards. I pick up each card in turn and gaze at them, striving simply to keep my attention on the feel of the cardboard in my hand and the patches of color and shape that reach my eyes. What if I were looking in a mirror? What if each of these cards, like the Emperor, was simply a reflection of me? After all, how could they not be my reflection?

A woman gazes up, a man looks down, a winged figure spreads their arms out above them. A scowling crowned figure hunches forward, cradling and clenching golden disks. And between the outspread wings and the clenching scowl: the teal booties and pauldrons of a man on a throne.

Laid out before me is a triptych mirror image. This is me, from outspread wings to clenched and golden wealth. I spread out across the sky. I hunch down over the landscape. I sit up straighter than straight in my four-pillared throne.

I try out a simple phrase in my mind: I love you all.

The cards are an empty mirror. I meet myself anew in their faces.

Looking

After refreshing our screens through pausing, and bracketing our stories and judgments with unknowing, we turn to the third step in the Daily PULL: looking.

In this step, we’ll approach the imagery of each card with as much specificity and detail as possible. We’ll notice what we notice, staying as embodied as we can, beginning with the shapes and colors that we see. If an emotion arises, we’ll ask ourselves where in the body that emotion makes its presence known. If a thought occurs to us, we’ll ask where and how we feel its impact.

Freewriting will anchor us in this exploration. I like to set a timer for this writing, treating it like a meditative practice and keeping it both consistent and aimless. I write until the bell goes off; that’s what makes my writing “free.” For further guidance on this writing practice, we can probably find no better advice than that of American author and Zen teacher Natalie Goldberg: 50

1. Keep your hand moving.

2. Lose control.

3. Be specific.

4. Don’t think.

5. Don’t worry about punctuation, spelling, grammar.

6. You are free to write the worst junk in America.

7. Go for the jugular. [ … ] Hemingway said, “Write hard and clear about what hurts.”

Now is a great time to pull out our journals and pens and ready ourselves to “keep the hand moving.”

Keeping the hand moving freely may allow us to forgive the unruliness of our minds. Our minds are perpetually in motion: perpetual-motion machines, ever cranking out concepts, judgments, feelings. We may not like that fact about ourselves, but try as we might, there’s little hope of vanquishing our own mentation—barring heavy anesthesia, a pretty intense concussion, or death. And since none of those options is particularly appealing, we might as well stop trying to clear our minds.

A few weeks ago, I was guiding a meditation practice in a large and open hall. It was a beautiful late-spring day—unseasonably warm, in fact. The windows of the hall were wide open. The soft yellow light of late afternoon filtered in. The members of my sitting group seemed to bask in the stillness. The quiet and ease were almost palpable.

And then a neighbor revved up their gas-powered lawnmower. I could feel the room tighten. I encouraged everyone to notice the oscillating whir of the two-stroke engine; how the buzz of the mower wasn’t just one sound, or one interruption, but was a whole sea of sound. I invited everyone to breathe in the scent of freshly cut grass. To extend their hearts into the awareness of summer approaching. To notice the competing sounds of birds and children. To feel the warmth of the sun on their eyelids. And, when the lawnmower finally stopped, to notice the easing of pressure in the ears and the sense of weightlessness that might be arising. What is the quality of quiet? I asked. Is this room truly without sound now?

Clearing the mind is as futile a task as blocking out unwanted noise. Lawns will be mowed! Concepts and feelings will gurgle up! But being at ease with the moment is not about wiping the moment clean. Instead, it’s a matter of becoming more and more curious about the texture and weave, the warp and weft, of our lives. Such curiosity lives in our five senses and our embodied connection to this planet. Mindfulness practice invites us to plunge into the world of our senses, becoming expert witnesses to our lives, ever more discerning and able to note our experiences.

Since the Tarot is predominately a visual medium, in Mindful Tarot our deep and expert witnessing begins with the eyes. But the other four senses are never far behind.

Check out the “Mindful Witness” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Check out the “Mindful Witness” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.

Mindful Tarot Step 3: Looking

My “unknowing” has helped me bracket the immediacy of my judgments and conclusions, and now I’m ready to really look at these cards. Looking mindfully at Tarot means seeing what’s right there on the surface: the shapes, the parallels, the gestures, the colors. It also means seeing what’s right on the surface of my reactions, noticing how my body responds to the images—noticing where my eyes are drawn or my heartstrings pulled. Language will help me be a Tarot connoisseur, and so I’ll be writing down as much as I can, working within a timed framework (as always, seeking the clear and consistent practice that will help me stay present in the moment).

I flip open my journal, pick up my Timex, and set the timer for five minutes, the length of this “looking” freewrite.

I begin to write. Like Natalie Goldberg suggests, I keep my hand moving across the page:

Two standing naked figures, trees at their backs, a cloud between them, a mountain in the distance—a gray angel with hair like leaves overhead—arms like her wings, both spread wide—the golden sun is her halo, raying out in every direction. The man’s tree has leaves like fire, the woman’s tree has apples … the yellow snake with its head by her ear wrapped around the tree like a garland—she looks up, he looks down.

Mountains again—asymmetrical and small. A man, a monarch, seated in a four-pillared throne—his beard full as an ancient patriarch’s—thin and sickly rivers stretch out on either side of his throne—his ankh-shaped scepter held upright—the ankh is about life, but this landscape is barren. Yet his eyes are kind. We see his shadow against the back of his seat. No halo sun. He’s looking into the sun.

No mountains, only hills. Another seated figure, two coins under his feet, and a bag of presumed wealth under his seat—he presents a third coin in both hands, like the world. A fourth coin overhead like a halo. He scowls. Behind him a verdant landscape—prosperous homes, beauty like Tuscany- cypress trees and gentle valleys and dales. In his foreground, only rocky soil.

These three cards all have commanding figures in them, but the relationship to rule is different in each one. I feel a pulling in my belly as I write this. Rule, leadership, control. The Emperor rules the entire landscape—rules over all of life. He’s ancient and seems kind, but his landscape is dry—almost as if he’s dried it up with his rule. The miser in the Four wears a crown—but all he seems to control is his wealth. The green landscape has nothing to do with him. He is alone. In the Lovers, the angel rules over this scene—she governs with benediction and blessing. She hears the petition of the heart—my chest feels full. My throat tightens slightly. The two monarchs rule, but are alone. Only the angel has company. Her care for those she governs is evident, even though her eyes are closed.

I feel the clenching of the miser’s body in my body. I’m hunching my shoulders. And suddenly I’m seeing that the Emperor looks hunched-over as well. Although he seems regal, there’s a tension in his shoulders and arms. He’s not comfortable! But nor are Adam and Eve. It’s as if they already know they’re naked and infamous; they already know that they are quote-unquote Adam and Eve. They seem entirely disconnected from each other. They are alone, too.

I find myself wondering who’s at peace in this spread—and the only answer I get is the angel—

The timer goes off. I lift up my pen and stretch a little, massaging my neck and my hands. I take a few slow, full breaths for good measure.

Leaning In

We’ve taken a mindful look at our cards, bracketing what we thought we knew in order to encounter more directly what was already there. We’re now ready for the final step of the Daily PULL. We’re ready to lean in more completely—to incline our bodies, hearts, and minds toward the living quick of this present moment. We’re ready to activate this Mindful Tarot practice as one of deep inquiry. We’re ready to let the cards pose our questions rather than help frame our answers.

In this final step of Mindful Tarot, we’ll again write freely—but without setting a timer. When leaning in, our aim is to write until we’ve landed on our question.

But how do we really lean in? It’s easy enough to incline toward the yum-yums of life: to tuck into some glorious pasta puttanesca, to snuggle warmly with our beloved, to breathe deep the salty mineral air of the sea. But it’s not so easy to lean into the things that are uncomfortable, unpleasant, or simply distasteful. As living organisms, we’re hardwired to feel an aversion toward the things that hurt or displease. We almost can’t help turning away. Yet, if we don’t incline our hearts toward the things we dislike, our lives will always be somewhat smaller and more guarded than they could be.

For this reason, gentle stretching is often a part of mindfulness classes. Stretching our bodies can help us understand where our “edges” are. If you kick out one leg and flex your heel, you can pretty easily experience what I mean by “edge.” I’m talking about that sense of tension and strain we can feel in the calf and hamstring—a sense that’s not necessarily unpleasant, although it’s sharper than our customary comfort zone.

If we then deepen the stretch, further flexing our heel, for instance, that sharpness intensifies. At a certain point—a different point for every body—the slight sense of strain and burn will become distinctly unpleasant. We’ve crossed over an edge. At the same time, we can also practice breathing into that edge, literally exhaling as we lean into the place of discomfort.

Interestingly, as we lean in to the stretch, our range of motion may very well increase. We may find a wee bit more ease as we first acknowledge and then breathe into what feels tight and painful. In this way, mindful stretching can help us learn through our very bones, muscles, and joints what it means to lean in.

Check out the “Mindful Stretching” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice. (Gentle reader, if you try this stretching at home, do please exercise kindness and caring wisdom for your body!)

Check out the “Mindful Stretching” mp3 file on my website: https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice. (Gentle reader, if you try this stretching at home, do please exercise kindness and caring wisdom for your body!)

Mindful Tarot Step 4: Leaning In

Before I lean in to these cards, it’s helpful to drop anchor for a few minutes—to find my balance and my ballast so that I can explore some of the more narrow and uncomfortable aspects of my experience. I set my Timex timer for five minutes of breath and body awareness. (I could also play the five-minute  “Dropping Anchor” meditation for this part of the PULL, at https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.)

“Dropping Anchor” meditation for this part of the PULL, at https://www.calyxcontemplative.com/mindful-tarot-practice.)

Once the meditation is over, I take a few conscious breaths and return my gaze to the cards. I will write until I find my question. I will trust that I’ll know when I’m done.

In this final step of the PULL, I will also let my curiosity guide me. I’m hoping to spark questions—to spark wonderment. If nothing feels juicy right off the bat, I will draw a couple more cards. Or I’ll turn to a guidebook—perhaps the companion book that came with my deck—but not as if I’m turning to the dictionary or to an oracle. I’m not hoping to anchor myself in a definitive meaning or in an answer. Instead, I’m trying to help clarify my questions. I’m looking for more “sparkiness,” more ways to engage my natural sense of wonder. And, yes, if I’m feeling really lost as I gaze at these cards, the words of another can help me find my way back to my own innate understanding. A guidebook, or the discussions in part 2 of this book, can help inspire me, or provide the “poke” or provocation that will allow me to settle ever more deeply into my own heart, my own body, and my own mind at this moment.

Today I pull two more cards—one for each “sphinx” in the Chariot spread—and get the Nine of Pentacles for the Four of Pentacles and the King of Wands for the Lovers.

Today’s expanded five-card spread

I pick up my pen and begin to write:

Of all the suits, Pentacles has always been the hardest for me—There’s a fundamental stinginess I recognize all too well—I can feel that tightness all throughout my body as I look at the miser card, the Four.

And now I’m wondering why I’ve always disliked the Nine. She’s a kind and graceful card, and yet I see that lady in the garden just tending to her wealth, keeping her falcon in the dark, and I think of Katherina in Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew and what it takes to tame a beautiful raptor. But there’s peace and bliss here, in the Nine. There’s a generosity here, and a freedom and a balance and an equilibrium I yearn for. I don’t know why I can’t see it.

Correction: I can see it, but I don’t want to (?)—I’m wearing blinders, like the falcon.

With the King of Wands I now have one more monarch on the table, and he’s perhaps my favorite of all the court cards. It’s so easy to lean toward him. He’s Henry V and Jon Snow and Katniss Everdeen and every hero who worries too much and yet rules like the wind. Is the worry the key? Or is it the role of protector—the caretaker—that catches my heart? There’s that pang in my chest …

Where I gravitate most in this spread is still that angel, my angel. Her wings and arms remind me of my moments in the hospital as chaplain, when I hold my own arms wide to anchor the space. There’s a deep yearning here to bring blessing…

Instead, I feel like the Emperor—that’s certain—and the miser—drawn toward control and tight structures—but these days I’m tilting more toward the world of taking care—Care! The Abode of the Pentacles. I need more Pentacles in my life … more of what I resist. (Why? How?) Can I recognize the grace of the Nine as what’s beautiful about the Emperor and the miser? Can I even recognize her grace per se? Why do I dislike the lady in the garden so much?

It’s the falcon, and his hood. Somehow I doubt my own ability to give blessing. I see myself as the lady. I see myself as the one who tries to control the wild and the free. I’m not the blind falcon. I’m the lady who does the blinding.

But I’m also the falcon. I have wings and can soar. Can I trust myself?

Can I possibly trust my own capacity to spread my wings? Can I believe in my ability to hold wide wings of compassion? To care for the weak and the vulnerable? Can I believe in my own angelic self?

The question feels done.

Can I believe in my own angelic self?

I set down my pen. I sit in mindful awareness of my breath for a few moments, or perhaps longer.

I gently bow my head toward the cards. I’m grateful for this practice.

And that’s it. The Daily PULL.

Wash. Rinse. Repeat.

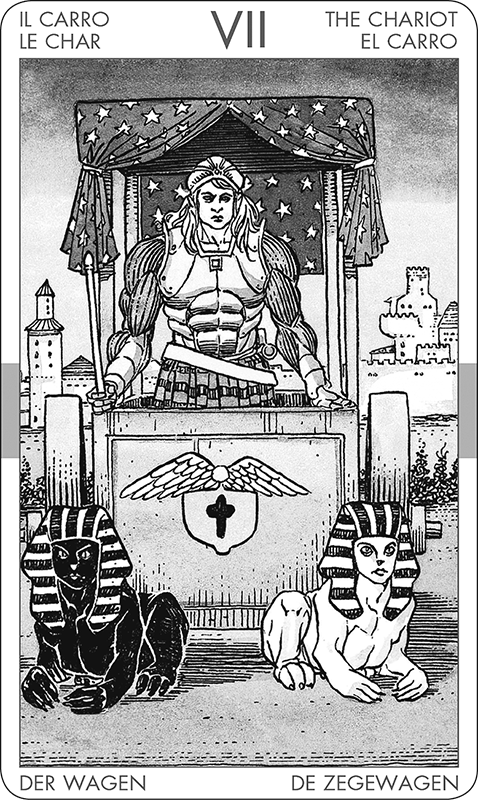

The Chariot Spread

In my daily PULL, I often use a simple three-card spread inspired by Trump VII. The Chariot offers an image of movement through stability. Notice how square and rigid the Charioteer’s wagon is. It’s almost as solid a structure as the Emperor’s throne. And the Charioteer’s two horses—traditionally sphinxes in the Waite-Smith imagery—seem to have settled in for a good long while. But don’t be deceived: this vehicle can take us anywhere. Its ability to move forward arises from the ways it encompasses both black and white, taking the darkness with the light, the shadow with the illumination.

In a Chariot spread, I begin with a central card. This is my Charioteer: the governing card that speaks to the moment at hand. Next I draw a card on the right, representing the white sphinx. This card might speak to that which is in the light: the most obvious or apparent feelings, thoughts, and judgments arising in this moment. Or perhaps the right card draws forward those aspects of my experience that I relish and enjoy. The white sphinx might evoke sides of myself, of my life, that feel “good.” The next card I pull represents the black sphinx: What is in shadow right now? My dark sphinx might draw forward subtext or background or simply aspects of my experience, right now, that feel aversive or unpleasant … or that even elude my conscious mind.

On the other hand, the two sphinxes may not oppose each other in any simple or obvious way. They are sphinxes, after all. The Chariot spread reminds us of the legend of Oedipus, the future king who risked his life in order to answer the riddle of the sphinx: “What walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three in the evening?” Oedipus rightly answered: “We humans. We crawl as babies, stand erect as adults, and stumble with a cane in the twilight of our years.” The job of the sphinx is not to offer answers but to pose questions. The sphinx asks us to examine our own self-nature. With the Chariot spread, we are invited to bring to light the full truth, light and dark, of our present experience.

46. Frankl never said these words. Stephen R. Covey (The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People) used the quote as a fitting description of Frankl’s philosophy. Covey claims to have found the message in a random book he stumbled across in the stacks of a university library. He can’t remember the source or author. See https://quoteinvestigator.com/2018/02/18/response/.

47. The Cloud of Unknowing and Other Works, translated by A. C. Spearing.

48. The Cloud of Unknowing and Other Works, translated by A. C. Spearing.

49. To determine the soul card, using Mary Greer’s method, you add together the numbers of your month, day, and year of birth. Then you add together each digit in the resulting number. If it’s greater than 9, add the digits again. For example, Jesus’s soul card would be derived as follows: 12 + 25 + 0 = 37; 3 + 7 = 10; 1 + 0 = 1. His soul card is Trump I, the Magician! (For Greer, the first number—10—would be his personality card.)

50. Goldberg, “The Rules of Writing Practice, in Wild Mind, 3–4.