FLEEING BABEL WITH MOTHER AND CHILD IN TOW

“Do the Mormons believe in having more wives than one?’ No, not at the same time. But they believe that if their companion dies, they have the right to marry again.

There is another class of individuals to whom I will briefly refer. Shall we call them Christians? They were Christians originally. We cannot be admitted into their social societies, in their places of gathering at certain times and on certain occasions, because they are afraid of polygamy. I will give you their title that you may all know whom I am talking about it [sic]—I refer to the Freemasons. … Who was the founder of Freemasonry? They can go back as far as Solomon, and there they stop. There is the king who established this high and holy order. Now was he a polygamist, or was he not?

MORMONISM GREW UP in the midst of a protracted battle—most pronounced, of course, in the North—over the proper sphere of men and women within the new economic realities of an emerging industrial nation-state. It made more sense to more and more of antebellum America’s middling sort for women to exercise absolute moral authority over children, giving men more time and energy to pursue their professional vocations and pecuniary responsibilities. Wives continued to monitor expenditures, ensuring that husbands did not fritter away the family’s hard-earned money. Early Mormonism utterly rejected this arrangement, propounding a less unequal distribution of parental authority: father and mother as a moral coalition party in the parliament of the home, with veto power going to the father. The Book of Mormon’s inclusion of women in its veiled Masonic ritual was the first plank in this platform.

Mormon feminists balk at the paucity of female role models in the Book of

Mormon and the rest of the Mormon canon. Melodie Moench Charles explains that “women are less significant than men” in the LDS scriptures. The Book of Mormon is “written by males,” she writes, “and because it focuses on religious leaders, civic leaders, and battles, it primarily records the actions, speeches and thoughts of males.”1 Even the Doctrine and Covenants, Smith’s subsequent private revelations, contain but a single revelation addressed exclusively to a woman: a harsh indictment against Emma, wife of the Mormon prophet, for her reluctance to practice polygamy.2

Only six women are named in the Book of Mormon—Eve, Mary, and Sarah (who perform no significant narrative role), Sariah and Isabel (who are criticized), and Abish (the only woman of name to exemplify faith and represent a force for good). Sariah, the wife of Lehi the great patriarch is faithful but contentious. Not unlike Abraham’s wife (Sarah), Sariah lacks vision, doubting Lehi for sending their sons to reclaim the plates of brass from Laban. Isabel’s character is patterned after that of the biblical Jezebel. As Charles explains, “Isabel is a harlot who is merely a vehicle for male degeneracy.”3 In some respects, the nameless daughters of Ishmael, invited to accompany Lehi to the promised land so that his sons will have wives and he and Sariah grandchildren, serve a mere biological function. Abish, a Lamanite woman converted “on account of a remarkable vision of her father,” is the exception.4

When the Book of Mormon alludes to biblical stories in which women play a prominent role, males take their place. The story of Teancum is one example. The male Teancum steals into the camp of a Lamanite enemy under cover of darkness and, using a javelin, spears him through (p. 404). Teancum’s heroics are reminiscent of Jael’s in the Book of Judges, the brave woman who drove a nail through the temples of Sisera (Judges 4:21).

The chief villain in the Book of Mormon is a woman, the ruthless daughter of Jared. Of the type of Herodias (Matthew 14:1–11)—the infamous New Testament coconspirator in the murder of John the Baptist—she resuscitates the Spurious Masonry of Cain in order to gain the throne for her father. “And it came to pass that she did talk with her father, and saith unto him, Whereby hath my father so much sorrow? Hath he not read the record which our fathers brought across the great deep? Behold, is there not an account concerning them of old, that they by their secret plans did obtain kingdoms and great glory?” Although her lover, Akish, carries out the killing of the king and “administer[ed] unto them the oaths which were given by them of old, who also sought power, which had been handed down even from Cain, who was a murderer from the beginning” (p. 553), we are told that “it was the daughter of Jared which put it into his heart to search up these things of old” (p. 554).

“This is not an impressive tally,” Charles writes, “for a book of [over five hundred] pages.”5 Mormon playwright Carol Lynn Pearson agrees that the “antifemale bias” in the Book of Mormon is a problem,6 whereas Lynn Matthews Anderson turns this on its head, arguing that the Book of Mormon can be seen as a feminist resource. “Taken altogether,” she writes, “the Book of Mormon makes a strong case for the complete revamping of our notions of hierarchical, patriarchal priesthood and the dismantling of patriarchal systems generally; indeed, it is, as Carol Lynn Pearson points out, the history of a fallen people and an unrelenting testament to the failure of patriarchy. Its treatment of women …—and an admittedly paradoxical one at that—is why the Book of Mormon will ultimately be viewed as a superlative ‘liberation text.’”7

Anderson’s thesis may be a thinly veiled apology for the faith, but it has more to offer a discussion about the Book of Mormon’s Masonic agenda than one might think. Anderson is right about the book’s underlying message—the “dismantling of patriarchal systems generally”—but this was means to another patriarchal end: an adoptive lodge system of the European Templar and Scottish variety. This becomes much clearer the moment we consider the important ways the Book of Mormon does not exclude or criticize women. John Whitmer’s personal copy of the Book of Mormon, for example, has underlined passages that seem to invite women to join the ranks of the “Priesthood” in a variety of capacities. An underlined passage in the Book of Alma reads, “He imparteth his word by angels, unto men; yea, not only men, but women also.”8

By today’s standards, the Book of Mormon is extremely condescending to women, to be sure. Even so, both Charles and Anderson are correct! The Book of Mormon, as I will show, can be seen as a subversive, radical feminist statement in opposition to the standing male order in America during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It invites men and women (and their children) to worship together at the altar of true manhood and thus true womanhood. More than doling out the usual patriarchal drivel in praise of motherhood, the text goes out of its way to include women as an essential part of the Masonic ritual celebration of fatherhood. Whether daughters, wives, or mothers, women in the Book of Mormon are portrayed as active and equal participants of a kind. The orthodox in Masonic circles believed that early Mormonism had a radical feminist agenda that might sway men and women of Masonic and anti-Evangelical sensibility to a new and more inclusive patriarchal way of thinking and living. Meanwhile, Evangelical Protestantism continued to back the Victorian family arrangement that would alienate fathers and sons, and possibly husbands and wives, in the years to come.

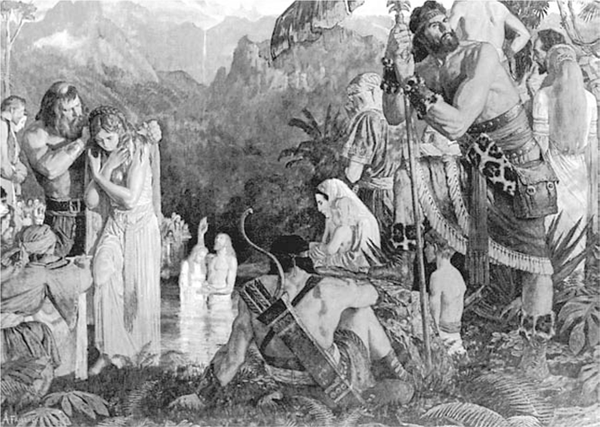

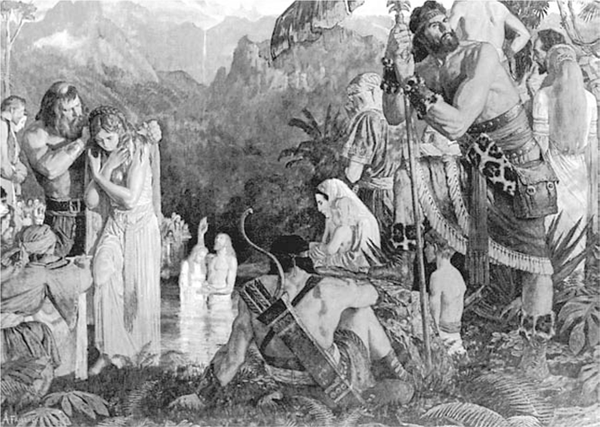

FIGURE 29 Arnold Friberg, Alma Baptizes in the Waters of Mormon

The Book of Mormon, large ed. (1957; reprint, Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1966).

The question of what to do with women had plagued Masonry beginning almost the minute the American Revolution ended. The more Masons hedged, the more Evangelicals saw their chance to move in for the kill. “As early as 1796,” Bullock writes, “Joseph Dunham identified the question, ‘Why are not ladies initiated into these Mysteries?’ as one ‘which has excited the curiosity and wonder, not only of that sex, but of the world at large.’”9 The response from the female Evangelical quarter expounded the cult of domesticity: the widespread Victorian belief in the innate depravity of men, women being a fount of virtue and morality. By excluding women from the lodge and its rituals, the fraternity seemed to sow the seeds of its own destruction. An anonymous Massachusetts woman, in an early, mildly anti-Masonic work entitled Observations on Free Masonry (1798), argued that women were initiated into Masonry at birth by virtue of their gender alone and that God instituted the lodge to teach the other sex what came naturally to women.10 But increasingly the prevailing wisdom held that the lodge was the abode of a band of sexually promiscuous drunkards.11 In the anti-Masonic literature, in particular, Freemasons were “utter Enemies of the Fair Sex.”12

The cult of domesticity had a number of flaws, giving men and women both too much power and too little over each other and over the public and private spheres, respectively. The separate-sphere doctrine was less an agreed-on division of labor and more a competition for greater moral influence in which men and women jockeyed for position. Two cults existed side by side, one lauding the virtues of true manhood, the other, true womanhood. Ironically, Freemasons were staunch advocates of the separate-sphere doctrine, not critics, excluding women from the lodge because they thought women ought to be home tending children. Paul Goodman explains that “by excluding women Masons intended no disrespect.”13 At the same time, as Dorothy Ann Lipson sees it, “the structure and the substance of Freemasonry were devoted to the communication of moral knowledge, which … was a purpose that impinged on a legitimate sphere of opinion and action by women.”14 How the Masonic husband exercised his lodge-given right to moral suasion at home without trampling on female toes was the problem. The Evangelical solution merely handed the role of moral arbiter and guardian of the home to women.

Masons begged to differ, positing a more cooperative albeit hierarchal relationship with the man on top and female partner a close second, lest tensions escalate and the home emasculate fathers and alienate sons. Masonry criticized what it construed to be the potentially disastrous social consequences of generations of young men raised exclusively by women. Women raised exclusively by their mothers, as Mary Ryan has shown, had some problems, too.15 But Masonry could offer little more than a romantic bandage, counseling wives to put their husbands and thus fatherhood on a pedestal. The ideal woman, according to Sarah J. Hale, famous antebellum defender of Freemasonry, was a creature with nothing but “unreserved devotion” for her husband. While he “is abroad in the world, seeking its employments and riches and honors,” she sits “at home and think[s] of him the live long day,” planning “all her arrangements … in reference to his return.”16 Interestingly, Hale devoted the bulk of her time to writing and speaking engagements; however, her characterization of the ideal Masonic wife and/or mother as “friend and companion of men,” never judge or adversary, is an apt summary of the Masonic critique of the cult of domesticity.

Early Mormonism brushed all this aside and simply opened the doors of its lodge to women. Since both sexes were “priests after the order of the Son of God” according to the Mormon Endowment ceremony, it followed that their relationship at home would be more equal, though not totally. The merits of the Mormon solution to the problem of the cult of domesticity may be open to question, but the Book of Mormon laid the groundwork for what at the time was a radical and inclusive alternative to what either Masons or Evangelicals were proposing.

IN LEHI’S DREAM of the Tree of Life, reminiscent of the so-called Journey of the Freemason in the World, those invited to eat at the Acacia include Sariah, who “partake[s] of the fruit also.” This shocking revelation occurs only nineteen pages into the story, Sariah’s mere presence at such a solemn and exclusively male ritual celebration of virtue being extremely problematic from an orthodox Masonic point of view. In fact, Lehi includes the whole family, calling them “with a loud voice” to join him at this Masonic banquet.17 Women in the narrative, who seem only to tag along for the ride, constitute a stream of inclusive consciousness. The invitation extended to Ishmael, his wife, and their daughters is not simply a matter of biological necessity but more of the same veiled inclusiveness in Masonic ritual. In the story of Nephi, loosely modeled after the story of Hiram Abiff, men and women (Laman and Lemuel and their respective wives) play the part of the three fugitive Fellow Craft Masons who murder the Grand Master and hide his body under rubbish on a faraway hill. Men and women (Nephi and Sam and their respective wives) also play the role of the faithful Fellow Crafts. There is no romanticism here: men and women appear on both sides of the Masonic law.

Two characters in particular underscore the Book of Mormon’s inclusive tendencies and adoptive agenda—a man and a woman, in fact. Alma, the young priest in the court of wicked king Noah, flees his employ. The murder of a prophet of the Lord, Abinadi, sends him packing. The king sends a military force to kill Alma, who hides, taking the opportunity to “write all the words which Abinadi had spoken” (p. 190). Alma’s flight into the wilderness can be seen as a variant of the Hiram Abiff myth and the instigation of a new Masonic order of the priesthood in the wake of the slaying of (Master Mason) Abinadi (the first three letters of the Book of Mormon name the same as Abiff). Alma “repented of his sins and iniquities, and went about privately among the people, and began to teach the words of Abinadi.” Importantly, “he taught them privately, that it might not come to the knowledge of the king” (p. 191). Then “Alma, having authority from God, ordained priests; every one priest to every fifty of their number did he ordain to preach unto them” (p. 193; emphasis mine). That Alma’s congregations do not exceed the number recommended in Morris’s Practical Synopsis of Masonic Law and Usage, which, it says, “should not, in general, exceed fifty or sixty,” can be seen as a none-too-subtle hint rather than mere coincidence, Masonic rather than biblical in origin and tone.18 And lest there be any doubt, the total population of Alma’s church is divisible by fifty, “about four hundred and fifty souls.”19 More important, Alma’s new lodge system, a veritable Masonic priesthood of all believers, clearly includes women.

The other major character in the Book of Mormon to propound an adoptive ritual is Abish, the enigmatic servant of a Lamanite queen. The story begins with the travails of the Nephite missionary to the Lamanites, Ammon, who converts their king, Lamoni. One of the king’s servants calls Ammon by another name, “Rabbanah, which is,” the Book of Mormon explains, “powerful, or great king.” It may allude to a password in the Royal Arch Degree, which is “Raboni” and signifies “Good Master, or Most Excellent Master” (p. 276).20 Is Lamoni’s conversion a Masonic raising? The text says he “fell unto the earth, as if he were dead.” Ammon reassures his Lamanite audience that the king is not dead but “sleepeth in God,” having been “carried away in God” (pp. 276–277). The effect is so powerful that Ammon and the entire Lamanite court, including the queen, sink into the same deep (Masonic?) dream state. Enter the queen’s servant girl, Abish, who performs the first Masonic levitation, the queen being the first to come forth (as a Master Mason). The name Abish begins with the same first three letters as Abiff; her character is a female incarnation of Masonry’s first Grand Master in name and deed.

What follows is remarkable (from an orthodox Masonic point of view). The queen raises the king. That a “servant” woman “raises” a queen, and then a queen a king, can be seen as a very clever way to address issues of both class and gender in relation to priesthood authority. The Lamanite queen is said to “clasp her hands” before “raising” her husband (p. 279). In the Scottish Rite, as Albert Pike explains, “the clasped hands … used by Pathagorus … represent the number 10,” a sacred number in Masonry and “among the symbols of the Master’s Degree, where it of right belongs.”21 And lest anyone doubt the intention here, the Book of Mormon states plainly that the mysteries are not the exclusive property of men: “He imparteth his word by angels, unto men; yea, not only men, but women also.”22

These and other instances of the incorporation of women in positive ways into the ritual are not without European Masonic precedent. This is important, for it suggests that Smith was operating outside the bounds of American fraternalism. His real crime may have been his position on the rightful place of women in the lodge when U.S. Masonry assumed exclusion to be the best policy.

Mormonism was not the first or only adoptive ritual in Masonic history, but it was the first of its kind in the United States. Moreover, the female degrees of the Eastern Star date back no earlier than the 1850s and 1860s. This ritual is built around the heroism of biblical women such as Ruth, Rahab, Esther, Mary, and Martha. The Good Samaritan “who stopped at the wayside to relieve the distressed” is the archetype of the order. Like Mormonism, it came out of Royal Arch Masonry. At first, husbands divulged some of the more benign Masonic secrets to their wives. Then the various signs and passwords were communicated “to a roomful of people at once,” after a formality that merely asked female initiates to respect the oath of secrecy without any other obligations.23 The Eastern Star has five points, one for each of five women of valor in the Bible (one a fictitious character named Electra). Esther’s brave rescue of her people figures prominently in the ritual (pp. 857–868). The Book of Mormon, culminating in the construction of the temple and the endowment, can thus be seen as an early Eastern Star-like inclusion of women, although European, Scottish, and hermetic in the main.

These days, the temple endowment has lost much of its original, male mystery. At one time, it even included an oath to avenge the murder of Joseph Smith “by any means.” Only recently has pressure from within led to the removal of the oath of secrecy, blood oaths, and signs, tokens and penalties that seem to have come straight out of Masonry and that apparently one might use to sneak through the pearly gates. Fanny Stenhouse (who describes her experience in the temple as simply an “ordeal”) underscores the sense of awe and mystery, indeed “fear,” that the nineteenth-century ritual evoked.24

Women of social standing in the early days of the church, like Fanny, were oblivious to its feminist possibilities. The temple, she writes, “united, man and woman, making one perfect creature … partakers of the plenitude of every blessing.” Going on, she confesses “how absolutely needful it was that [her] husband and [herself] would become partakers of those mysteries” (p. 189; emphasis in original). What frightened her most was not polygamy so much as “blood-curdling oaths” that she had no doubt “would be sternly enforced” (p. 190).

Not only did the temple include women, but women empowered women (mostly out of respect for modesty, mind you). Fanny was “anointed” by a woman, the venerable “Miss Eliza R. Snow, the poetess, and a Mrs. Whitney” washed her from head to toe, consecrated her with olive oil, and blessed her with good health, wisdom, and eternal life (pp. 193–194). Was there anything quite so radical, so ostensibly feminist, in Evangelical or Masonic circles in America? In the main ceremony, Fanny witnessed husbands and wives, men and women, made equal partakers of the new and everlasting covenant. In the end, though, her account does little more than poke fun at the ritual’s primary symbol, finding laughable “a small real evergreen, and a few branches of dried raisins … hung upon it as fruit” (p. 196)—failing to see the connection to the acacia.25 Had she read her Book of Mormon, she might not have been so critical, so incredulous, quite so transparently unfair and uninformed. Mr. T. B. H. Stenhouse only wanted for his beloved Fanny what Lehi had loudly proclaimed and offered to his family—to come and sup with him at the table of manhood. Poor Fanny! She lost her nerve and then pointed an accusing Evangelical finger once safely in the arms of Jesus to the east, failing in the end to remove herself completely from the Masonic dreamworld of Mormondom.