A BIBLE! A BIBLE! WE HAVE GOT A BIBLE

“Do you believe in the Bible?” If we do, we are the only people under heaven that does, for there are none of the religious sects of the day that do. “Wherein do you differ from other sects?” In that we believe the Bible, and all other sects profess to believe their interpretations of the Bible and their creeds…. “Is there anything in the Bible which licenses you to believe in revelation now-a-days?” Is there anything that does not authorize us to believe so? If there is, we have, as yet, not been able to find it. “Is not the canon of the Scriptures full?” If it is, there is a great defect in the book, or else it would have said so.

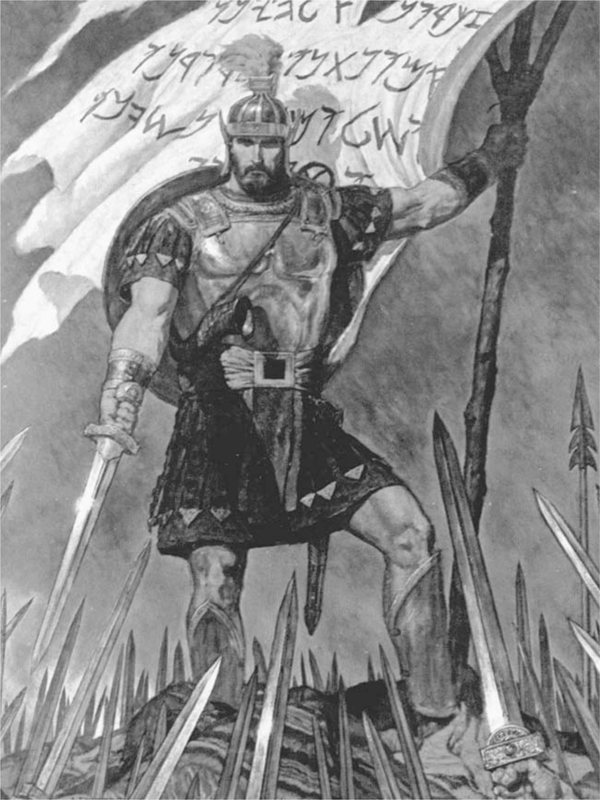

FIGURE 30 Arnold Friberg, Captain Moroni Raises the Title of Liberty

The Book of Mormon, large ed. (1957; reprint, Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1966).

AMICROSCOPIC, SOURCE-CRITICAL ANALYSIS of the Book of Mormon reveals a nuanced biblical subtext. Importantly, the Book of Mormon quotes extensively and directly from the King James Version: Exodus 20:2–4, 3–17; Isaiah 2–14; 48:1–49:26; 52:7–15; 53:1–12; 54:1–17; Micah 4:12–13; 5:8–11; Malachi 3, 4; and Matthew 5–7. In some cases, the wording has been altered slightly. Many such emendations are of the italicized words in the Authorized Version. As Wesley P. Walters shows, the Old Testament passages quoted in the Book of Mormon support Smith’s eschatological views.1 The books of Nephi quote extensively from the Book of Isaiah, castigating the atheism, hedonism, and intellectualism of the rich and mighty.2 The Book of Mormon Jesus repeats verbatim the Sermon on the Mount, driving home the need for a global, transcontinental awakening.3

There can be little doubt concerning the origin of no less than one hundred and fifty proper names in the Book of Mormon—nearly half the total in the corpus—since they correspond exactly to those in the King James Version.4 Apologists maintain that Smith merely “made a concerted attempt to retain the biblical (King James) spelling wherever the name was already known from the Bible, while he newly transliterated all other names.”5 There has been considerable debate over the possible origin of the remaining two hundred names. Blake Ostler argues that although they “could be biblical variants, [some] are difficult to explain as Joseph Smith’s inventions.”6 Critics are quick to conclude that Smith invented them, a process one scholar has termed “graphic glossolalia.”7 Brodie first thought they could all be explained as “Biblical names with slight changes in spelling or additions of syllables.”8 She is quite right, of course.9 However, these and other biblicisms can be seen as having a Masonic origin, too.

The Book of Mormon alludes instead to various fraternal rituals and emblems; its manifold corrections of and departures from the King James Version can be seen as Masonic, aimed at a very specific antebellum audience with a predilection toward singing the praises of the Bible—but in a decidedly anti-Evangelical key. Masons believe in the Bible, but, not unlike Mormons, “only as far as it is translated correctly” (the eighth article of faith in Mormonism). “Every well governed Lodge,” Webb writes, “is furnished with the Holy Bible, the Square, and the Compass.”10 Carnes points out that the ritual of the Odd Fellows (an order established in 1819) consists entirely of passages taken directly from the Bible and biblical paraphrases. “Yet the early ritualists,” he explains, “did not hesitate to modify Scripture to suit their purposes.”11 The lecture for the Royal Arch Degree in Webb also cuts and pastes from the Bible, paying no mind to chronology, beginning with Exodus 3:1–6, then 2 Chronicles 36:11–20 and Ezra 1:1–3, then back to Exodus 3:13–14, then on to Psalms 141, 142, and 143, more from Exodus—this time 4:1–10—then Haggai 2:1–9, 23, Zechariah 4:6–10, a passage—surprisingly—from the New Testament, John 1:1–5, and then back in time yet again, to Deuteronomy 31:24–26, Exodus 25:21, 16:32–34, and Numbers 17:10, then ahead in time to Hebrews 9:2–5, then back to Amos 9:11, and finally back to Exodus 6:2–3. Indeed, the perennial complaint from literary quarters—that the Book of Mormon is a pastiche of biblical citation and paraphrase—does not take into account that this might be a direct result of a mimetic agenda rather than simply poor writing. Readers familiar with the stilted prose of the Royal Arch lecture and its recapitulation of the biblical story of Moses and the flight from Egypt and journey to the promised land might well find the Book of Mormon to move along nicely. One can see, however, why it might seem little more than plagiarism of the Bible to those for whom Masonic legend is a complete mystery.

The Book of Ether, a chapter book of sorts that appears near the end of the Book of Mormon, contains the account of an extinct and ancient race of people who came to the new world to escape the destruction around the time of the Tower of Babel. This record of their exploits and eventual destruction has been discovered by a second wave of immigrants who fled Jerusalem just before the Babylonian onslaught and thus escaped captivity—which is why it appears nearer to the end of the Book of Mormon than at the beginning where it perhaps belongs. If only the Book of Mormon had been written in the concise prose featured in Ether! The remaining fourteen chapter books that make up the Book of Mormon seem woefully inadequate by comparison.

Ether, the last of the Jaredite prophets, documents the tragic downfall of his people, a chosen race granted respite at the Tower of Babel. They emigrate to America and become a mighty and powerful nation under God. Like the ancient Israelites, the Jaredites are plagued by corrupt leadership. Numerous secret societies also threaten the peace, security, and well-being of this covenant people. In an effort to stem the tide of wickedness, God sends prophets to remind them of their sacred obligations. They repent and peace is restored. Still, in the end, the Jaredites are destroyed as punishment from on high for individual and collective sin.

The account of the events leading to their downfall either paraphrases or quotes the Bible verbatim. For example, The Book of Ether claims to be the record of a “people who were destroyed … at the time the Lord confounded the languages of the people.” This is a slight emendation of Genesis 11:9, which says “the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth.” In Ether, the Lord confounds “the languages of the people,” a point of clarification that contradicts the Bible’s contention that only one language existed before the confusion of tongues. This is the first of several departures from the logic and wording of the Bible.

The Lord, Ether says, “swore in his wrath that they should be scattered … and according to the word of the Lord the people were scattered.” The brother of Jared, the main character in the drama, pleads on behalf of friends and family. This seems to be an allusion to Abraham and his plea on behalf of the wicked of Sodom (see Genesis 18:23–33). And so the Etheric scenario is more familial and sanitary—less problematic from a moral standpoint. The brother of Jared is instructed to inquire of God “whether he will drive us out of the land,” turning Exodus 6:1 on its head. Like the biblical Noah, the brother of Jared is then admonished to gather together “male and female of every kind.” He gathers “seed of the earth,” either a rationalization of Genesis 6:21 (“all food that is eaten”) or a new reading for Genesis 7:3 (“to keep seed alive upon the face of all the earth”).12 The references in Ether to “fowls of the air” and “swarms of bees” hark back to Genesis 6:20, where Noah is commanded to bring “fowls after their kind” and “every creeping thing of the earth after his kind.”

The Jaredites journey into the wilderness, like the Israelites in the Old Testament. They travel “down into the valley of Nimrod,” which is said to border the wilderness. Similarly, the Israelites flee Egypt and camp “in Etham, in the edge of the wilderness” (Exodus 13:20). In Ether, God “go[es] before [the Jaredites] … in a cloud” and gives “directions whither they should travel,” a paraphrase of Exodus 13:21: “And the LORD went before them by day in a pillar of a cloud, to lead them the way.” The Deity appears to the brother of Jared in a cloud. Like Moses, too, he is not permitted to look him in the face.

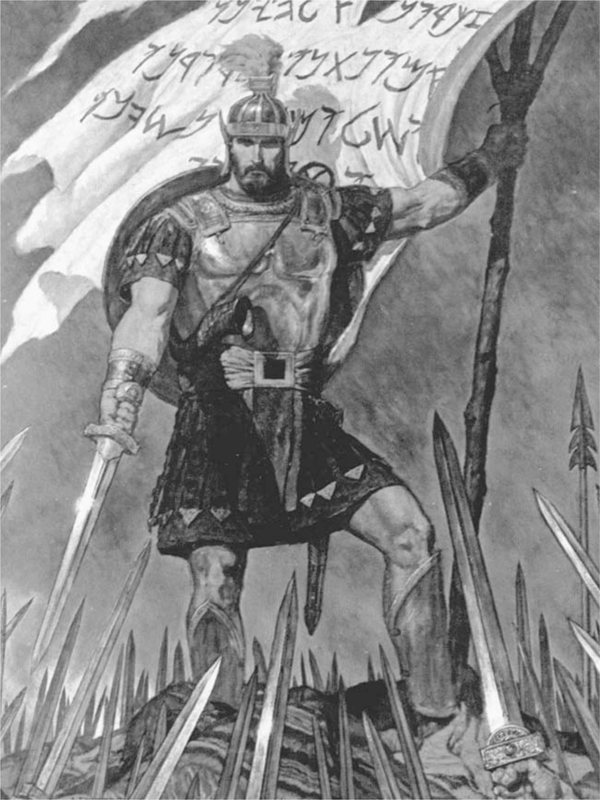

FIGURE 31 Jewel of an Ark Mariner

Robert I. Clegg, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (Richmond, Va.: Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply, 1966), 1:104.

The departures might be viewed simply as minor criticism and a slight steadying of the Ark. In the Book of Ether, God is said to “talk with them,” that is, the people as a whole—a democratization of the biblical understanding of divine revelation. Exodus 19:9 reads: “And the LORD said unto Moses, Lo, I come unto thee in a thick cloud, that the people may hear when I speak with thee.” The Israelites simply witness the “thunder and lightnings” atop Mount Sinai, a sign of God’s communication with Moses (Exodus 19:16 ff.). They do not actually hear Him talk to Moses. The Jaredites, on the other hand, are privy.

Not unlike Noah, the brother of Jared builds a vessel to escape the discord. He quickly finds himself suspended between the horns of an engineering dilemma, however, for the airtight watercraft that will carry himself, his family, and others to the land of promise have no apparent means of illumination. This design flaw is resolved by inviting the Deity to touch sixteen luminescent stones that will provide light for the long sea journey. Another departure from the Noachian narrative? A slight modification to the Noachian ark in the Bible—which had windows? Perhaps the construction of the Jaredite barges alludes to Jonah’s aquatic incarceration in the belly of a great fish. “What will ye that I should do that ye may have light in your vessels?” the Almighty explains to the brother of Jared, “For behold, ye cannot have windows, for they will be dashed in pieces…. For behold, ye shall be as a whale in the midst of the sea.”

Such eccentricities may not be simple biblical revamping but Masonic recitative based on the Bible, that in the Master Mason and Royal Arch Degrees in particular. The Tower of Babel, for example, has special significance for Masons. It is the legend of the Twenty-first Degree of the Scottish Rite, or the order of the Noachites, and an important symbol of the craft in general. In fraternal legend, its destruction signals the moment darkness fell on all mankind as a consequence of pride and ambition. Masonry may reach back to the Garden of Eden, but it began at Babel. In Masonic lore, a period of peace and harmony preceded the confusion of tongues—the direct result of an infusion of Master Masons from the East. Mackey explains in his Lexicon of Freemasonry that after the flood “man again rebelled, and as a punishment of his rebellion, at the lofty tower of Babel, language was confounded, and masonry lost…. The patriarchs, however, were saved from the general moral desolation and still preserved true masonry, or the knowledge of [the unity of God and immortality of the soul] in the patriarchal line.”13

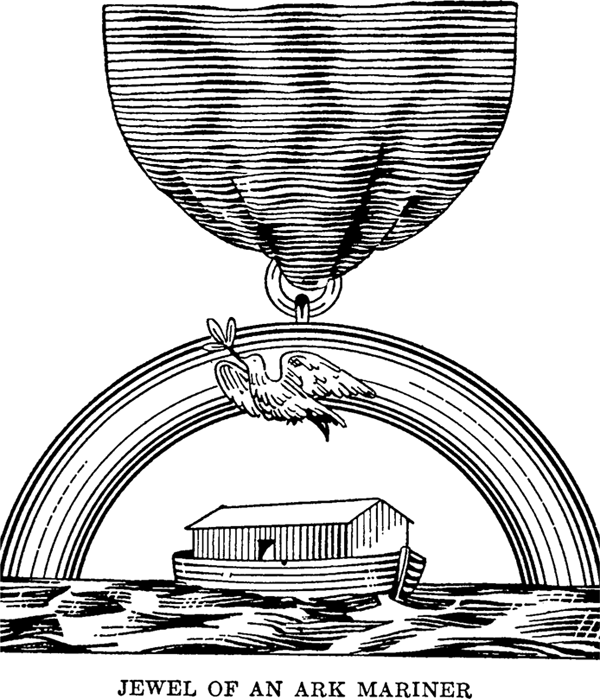

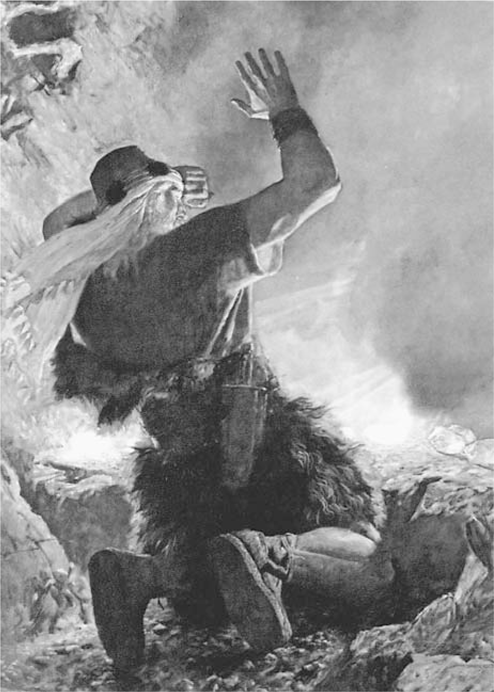

FIGURE 32a Moses

Robert I. Clegg, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (Richmond, Va.: Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply, 1966), 2:714b;

Noah is the titular head of the true Masonry that was not confounded. “Noachite Masonry,” Mackey points out, “date the commencement of their order from this destruction,” not to be confused with “Spurious Freemasonry” that also originates at Babel (p. 30). In other words, the separation of Masonry into Noachite and anti-Noachite at the time of the Tower of Babel can be seen as a twin birth that not unlike that of Jacob and Esau spawns a bitter rivalry.

FIGURE 32b Arnold Friberg, Brother of Jared in the presence of the Deity

The Book of Mormon, large ed. (1957; reprint, Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1966).

The flip side of this is “the ancient practice of Masons conversing without the use of speech” by means of hieroglyphics and symbols, claiming to “possess an universal language which men of all languages can understand.”14 Templars communicate using a secret system of Egyptian characters; a facsimile appears in Arkon Daraul’s book, Secret Societies.15 In the order of the High Priesthood of Thebes, the initiate is taught “the peculiar hierogrammatical script” (p. 132).

In the Third Section of the Master Mason Degree, the beehive and ark are important emblems, the former symbolic of industry, the latter, Webb explains, “emblematic of that divine ark which safely wafts us over this tempestuous sea of troubles.”16 Mackey’s discussion of the Noachites in Masonic legend casts light on the barges. Noah’s aquatic journey is pregnant with Masonic possibility. Mackey explains: “The entrance into initiation was symbolic of his entrance into the vessel of salvation; his detention in the ark was represented by darkness and the pastos, coffin, or couch in which the aspirant was placed; and the exit of Noah, after the forty days of deluge, was seen in the manifestation of the candidate, when, being fully tried and proved, he was admitted to full light, amid the rejoicings of the surrounding initiates, who received him in the sacellum or holy place.”17

The sixteen luminescent stones may allude to the pot of incense, said to “glow with fervent heat” and symbolic of the pure heart of the initiate, or simply to the lodge candles, its only source of light. As Clegg explains, “a singular regulation is that there shall be no artificial light in the Lodge-room.”18 Hence the barges (or rather lodges) are lit using supernatural light. Normally, there are three candles, not two, but then again the Jaredite barges may be lodges of the esoteric (Scottish or Egyptian?) kind. If so, then perhaps each is given its own Urim and Thummim to provide the illumination required to make the long and perilous journey.

A white stone is also the symbol of the Mark Degree in the York and American Rites, where a passage in Revelation is the text: “To him that overcometh will I give to eat of the hidden manna, and will give him a white stone, and in the stone a new name written, and no man knoweth, saving he that receiveth it.”19 In the Masonic ritual, it is said to represent the Covenant that the initiate makes with the Creator. This does not explain, however, why there are two such stones per lodge, unless, perhaps, one is for males and one for females.

The brother of Jared’s epiphany has a Masonic ring to it as well. His great faith and purity of heart permit him to stare Jehovah in the face and thus discover firsthand that the God of the Old Testament is the spirit of the preexistent Christ. And what might this be? Perhaps a burning bush episode in the style of the Royal Arch ceremony, where an unseen Mason impersonates the Deity and the initiate Moses? (This ceremony, incidentally, horrified Evangelicals because Masons, mere men, took on the persona of divine beings.)20

Be that as it may, the Jaredites arrive in America at long last. Theirs is the first of three such Puritan-like transplantations, their meteoric rise and fall from grace blamed on “secret combinations,” an “apostate priesthood order,” we are told, that traces its origins to Cain. Its tenacity and uncanny ability to insinuate itself into Noachite society—Jaredite and then Nephite—becomes the raison d’être and moral locus of the larger narrative. The daughter of Jared concocts a scheme to murder the aging king, Omer, so that his son and her father will inherit the throne. She seduces Omer’s best friend, Akish, the price of sleeping with her being the head of poor unsuspecting Omer (an inoffensive chap by all accounts). The events surrounding Omer’s beheading recall that of John the Baptist in the New Testament. Elements of the seduction of Samson by Delilah are there, too—another classic Masonic proof text.21 Omer’s murder by his best friend recalls Abel’s slaying by a dear brother, Cain, and becomes the basis for a counterfeit male order.

The daughter of Jared shares her bed and her knowledge of a secret order dating back to Babel “that … by their secret plans,” she explains, “did obtain kingdoms and great glory.”22 Akish’s adultery is his adoption into the ranks of Spurious Masonry. He makes a pact with Jared’s “kinfolk” who not only “sware unto him” but take an oath “handed down even from Cain, who was a murderer from the beginning” (pp. 553–554). This unholy band is “kept up by the power of the devil to administer these oaths unto the people” and is the origin of the so-called secret combinations (p. 554).

All this comes to us not from Evangelical sources alone but from contemporary Masonic ones too. Once again, the Bible and the Bible alone is not the whole story. George Oliver, Knight Templar and premier nineteenth-century exponent of such romantic fancy, spoke for many when he wrote:

The Rites of the Science which is now received under the appellation of Freemasonry were exercised in the antediluvian world, received by Noah after the flood, practised by man at the building of Babel, conveniences for which were undoubtedly contained in that edifice, and at the dispersion spread with every settlement, already deteriorated by the gradual innovations of Cabiric priests, and moulded into a form, the great outlines of which are distinctly to be traced in the Mysteries of every heathen nation, exhibiting the shattered remains of one true system whence they were derived.23

Oliver’s ideas were indebted to the writings of G. S. Faber, in particular his widely read 1816 tome The Origin of Pagan Idolatry, which accused Masons of building the Tower of Babel in the first place.24 Oliver’s was a more positive spin on Masonic involvement, blaming the fiasco on a clandestine element.25 Masonic invention like Oliver’s can be seen as a more likely parallel for the Book of Mormon’s discussion of the secret societies that it means to criticize. In one Masonic encyclopedia, secret societies are defined as “members [who] take any oath binding them to engage in mutiny or sedition, or disturb[ing] the peace, or whose members and officers are concealed from society at large [and] have been declared unlawful in various countries.”26 Masons are the arch enemies of all who would pervert secrecy and oath taking. Ramsay, it is worth noting, thought that Cromwell’s Fifth Monarchy Men were “Assassins of the Third Degree” and believed Charles I to be a modern-day victim of latter-day Saracens—disturbers of the public peace writ large (1:109).

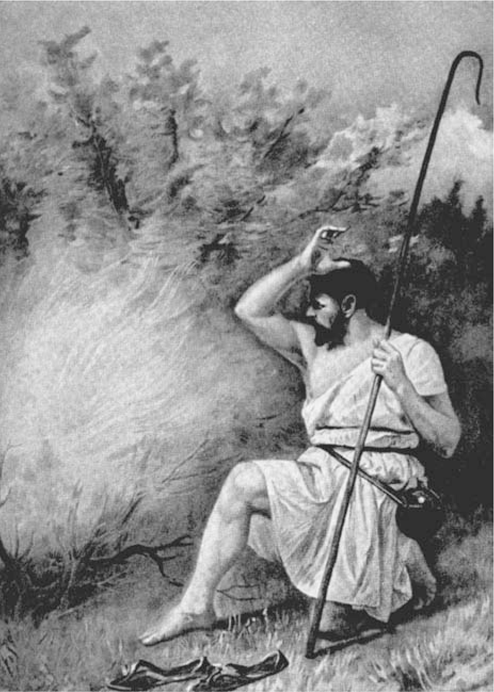

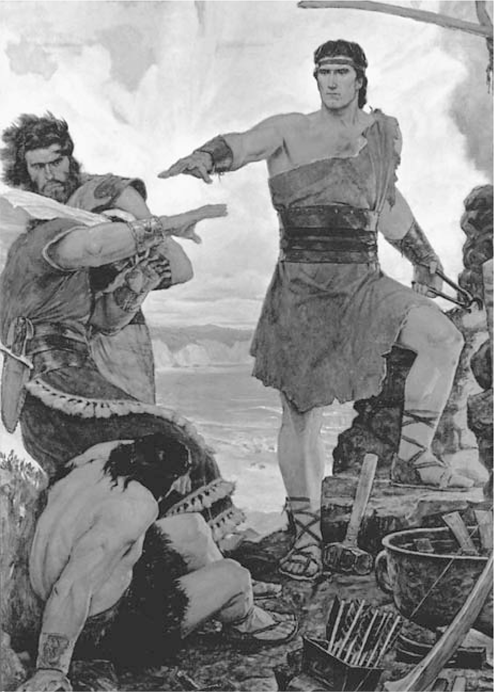

FIGURE 33 Arnold Friberg, Young Nephi Subdues His Rebellious Brothers

The Book of Mormon, large ed. (1957; reprint, Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1966).

The Book of Ether thus offers a variety of clues on how to read the Book of Mormon. Placing it at the end, rather than at the beginning, may not have been the best strategy in hindsight, but regardless it operates very much like the Book of Exodus in the Pentateuch: it is the basis for everything before and after. One reads Genesis with Exodus in mind; so, too, reading the first two books of Nephi (First and Second Nephi) with full comprehension requires a certain prescience. Having read Ether, the Book of Mormon’s overarching Masonic-Evangelical agenda is less likely to be misconstrued as exclusively one or the other. Ether also alerts us to the fact that the pattern of escape, flight, and resettlement throughout constitutes a series of Royal Arch–like epic journeys in the never-ending male search for the long-lost book, the key to greater concord along gender lines in a world turned upside down by scheming Masonic men and Evangelical women.