THE SEARCH FOR THE LONG LOST BOOK IN THE BOOK OF MORMON

“How and where did you obtain the Book of Mormon?” Moroni, who deposited the plates in a hill in Manchester, Ontario County, New York, being dead and raised again therefrom, appeared unto me, and told me where they were, and gave me directions how to obtain them. I obtained them, and the Urim and Thummim with them, by the means of which I translated the plates; and thus came the Book of Mormon.

THE BOOKS OF NEPHI, the first of fifteen books in the Book of Mormon, pick up where the Book of Ether leaves off. Another exodus. Another beheading. Yet another Noachian sojourn and protracted fall from grace. Another Masonic battle to the death, too. The Jaredites destroy each other, and the Nephites are wiped off the face of the earth by their brothers, the Lamanites. The journey begins with a Hebrew prophet named Lehi who flees Jerusalem before the Babylonian incursion, taking his family with him. Lehi is a visionary. I have already discussed how his dream of the Tree of Life expounds the so-called Journey of the Freemason in the World. His journey to the promised land and the events that lead to the extermination of half his posterity can also be seen as one long Masonic recitative based on the Royal Arch quest for the lost book of the Law.

Nestled safely in a wilderness camp, Lehi has already tipped his hand in some respects, for pitching a tent just three days from the Holy City is precisely what any Knight Templar (worth his salt, that is) is supposed to do and where he ought to make camp. As Clegg explains:

The tent, which constitutes a part of the paraphernalia of furniture of a Commandery of Knights Templar, is not only intended for a practical use, but also has symbolic meaning. The Order of the Templars was instituted for the protection of Christian pilgrims who were visiting the sepulcher of their Lord. The Hospitalers might remain in the city and fulfil their vows by attendance on the sick, but the Templar must away to the plains, the hills, and the desert, there, in his lonely tent, to watch the wily Saracen, and to await the lonely pilgrim, to whom he might offer the crust of bread and the draft of water, and instruct him in his way, and warn him of danger, and give him words of good cheer.

The Templar, as Lehi surely does, turns his back on luxury and wealth, giving all he has to any passersby. “Such events as these,” Clegg continues, “are commemorated in the tent scenes of the Templar ritual.”1

That Lehi erects an “altar of stones” is another clue to the precise reason—Masonic through and through—for his wilderness retreat.2 Stone worship, not surprisingly, gets the nod in Clegg as well. (That Masons would worship stone seems obvious.) “The influence of this old stone-worship, but of course divested of its idolatrous spirit, and developed into the system of symbolic instruction,” he writes, “is to be found in Freemasonry, where the reference to sacred stones is made in the Foundation-Stone, the Cubical Sone, the Corner-Stone, and some other symbols of a similar character.”3

A stone altar will not do in the long term, however. Indeed, for Lehi to do his job (as Grand Master), he requires the services of a good monitor. And so he must send his sons (Laman, Lemuel, and Nephi) on a quest back to the wicked city, ostensibly to reacquire a family genealogy, written on (brass) plates in the possession of a capricious uncle named Laban. And if there is anything to the names of the Book of Mormon, it may not be a coincidence that Laban in the Bible (Jacob’s father-in-law) is a distant relative. The Hebrew root from which the name derives means “white.” It can also be translated as “to make brick”—the sort of Hebrew word and biblical proper noun a Mason might be inclined to know and want to make more out of than perhaps is merited.4 In Masonic parlance, “laban” is the word for the white lambskin apron of the Master Mason. In the Knight of the Sun, or Twenty-eighth Degree of the Scottish Rite, Laban is the proper name given to “all carnal concupiscence” (taking its cue from the Sohar) which “will be whitened of its impurity.”5 Interestingly, Nephesch is the name of its spiritual counterpart in this degree (p. 757). However one views this, Laban’s name denotes something Masonic.

As the story unfolds, the plan is to get Laban to relinquish his copy of the genealogy—which turns out to be the Torah—for a tidy sum of Lehi’s entire savings. Nephi and his brothers go “down to the land of [their] inheritance” and “gather together gold, and silver, and precious things,” the first of several Royal Arch treasure hunts. In the meantime, Laban hatches a plot to rob them of their gold and silver, along with their lives. His young nephews do not see anything coming, holding up their end of the bargain but leaving empty handed, hiding in the cavity of a rock (an allusion to the burning bush episode in the Royal Arch ritual). All seems lost. Laman and Lemuel grow angry with Nephi for refusing to give up. An angel appears just in time to stop Nephi’s murder at their hands (an allusion to the murder of the Master Mason Hiram Abiff). There is no need to squabble, the angel assures them: the Lord will deliver Laban into their hands (just as he delivered Pharaoh into the hands of the ancient Israelites, in effect). Nephi screws up his courage and returns to Laban’s house under cover of night to find his uncle “drunken with wine.” Another divine communication constrains Nephi to remove Laban’s “head with his own sword” (here we go again, except that this decapitation has the permission of the Deity and thus the blessing of Masonry). Nephi puts on Laban’s armor as a disguise and asks the servant of the house, Zoram, to take him to the “treasury.” After securing the brass plates, Nephi invites Zoram to follow him “without the walls” of the city (where Laman and Lemuel wait anxiously). At first, Nephi’s brothers imagine Laban has come to kill them. Nephi explains that it is he. Nephi buys Zoram’s silence with a promise of freedom and seals it with an oath of allegiance. When he and his brothers present the plates to Lehi, we are told that their family history and the Torah are one and the same. Here, too, the text tips its hand. Nephi and his brothers have just come back from a Royal Arch-like quest for the lost, or in this case almost lost, book of the Law.

The story of Laban—nestled in the middle of the Masonic allegory of the Tree of Life and the veiled Masonic raisings of Lehi and his sons—recounts the unfortunate but unavoidable execution of a Masonic miscreant and corruptor of the order. Laban is a high-ranking city elder of the Masonic kind. “Behold [Laban] is a mighty man,” Laman and Lemuel bitterly complain, “he can command fifty, yea, even he can slay fifty; then why not us?”6 The number fifty, as I have already mentioned, can be interpreted as a cipher for a Masonic assembly—Spurious or Cainite, in this case.7 However, Laban’s beheading is an important clue to the precise nature of the book’s hidden Masonic agenda.

Brooke points out, for example, that the decapitation of Laban resembles the story in the Templar ritual of “a sword being used to behead a sleeping enemy.”8 In the Chivalric ritual for the High Priesthood of Thebes, the aspirant is “handed a sword and told that he must cut off the head of the next person he [meets] in the cave and bring it back to the king.” The Theban initiate is also instructed to seize his victim by the hair.9 In the Knights Templar ritual, as described in Mackey, the initiate is struck on the neck (ever so lightly) with his own sword.10 In the Royal Arch Degree, the symbolism is clearly spelled out: “The stiff neck of the disobedient shall be cut off by the sword of human justice, to avert…” (the rest is blotted out).11 Laban is the first person Nephi encounters after his return to the city. He takes Laban “by the hair of the head” when performing the grisly surgery.12 In the Templar ritual, again in Mackey, after the beheading ceremony the initiate is “clothed with the various pieces of his armor, the emblematic sense of which [is] explained to him.”13 In Alexander Slade’s eighteenth-century anti-Masonic polemic The Freemason Examin’d, the ritual is satirized for “stripping” the aspirant before clothing him in his Masonic attire.14

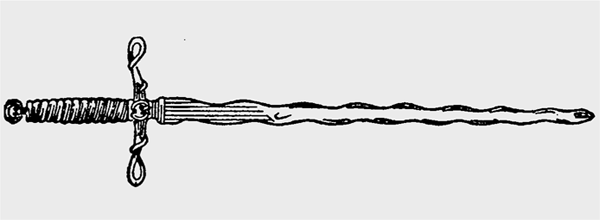

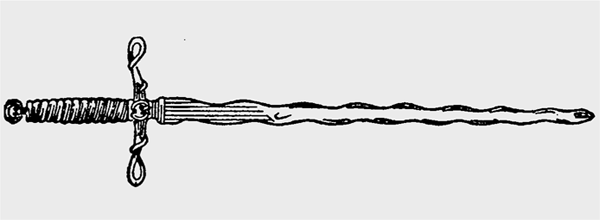

FIGURE 34 Wavy, or Flaming, Sword of the Tiler

Robert I. Clegg, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (Richmond, Va.: Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply, 1966), 1:359.

The instrument of Laban’s destruction, his own sword, is another important clue to the book’s hidden Templar agenda. “And I beheld his sword,” Nephi says, “and the hilt thereof was of pure gold, and the workmanship thereof was exceeding fine; and I saw that the blade thereof was of the most precious steel.”15 The description of Laban’s sword may be an allusion to the no less ornamented “Flaming Sword of the Tiler,” pictured in figure 34. It should always be drawn, and the Tiler ready at all times to safeguard the treasury of the lodge against “cowans” who hope to abscond with any of its Masonic vestments and other “furniture.” Laban is not only asleep at his post, but falling-down drunk in the street, making him a rather poor excuse for a Tiler, indeed. That he pays for this with his life is harsh and rather undignified, but the punishment presented in the Templar ritual, in fact!

Nephi, however, is constrained (by no less than an angel) to murder Laban in his sleep. His scruples are consistent with those of a Knight Templar, who must never shed innocent blood. In the American Templar oath, the aspirant pledges to pursue “a warfare which requires no swords, demands the shedding of no blood save the cross of Him who went about doing good.”16 Yet there comes a time when the peace-loving Christian Knight must of necessity engage in conventional warfare lest he break another oath: to defend the weak against the machinations of the strong. Laban’s refusal to hand over the genealogy (for a fair price) threatens Nephi and his posterity. Without the scriptures, they are likely to forget their covenant with the Creator. (The Mulekites, contemporaries who also flee Jerusalem but without the Torah in hand, fall into disbelief shortly after arriving in America.) Laban’s death is not unwarranted. Beheading, moreover, is the ultimate penalty for not honoring one’s fraternal vows. Laban is thus a fallen Christian Knight of the highest order and is executed accordingly.

Nephi’s handling of the servant, Zoram, is also consistent with Templar practice, that is, habeas corpus of the medieval, chivalrous kind. Zoram is oathbound. When Nephi says, “Our fears did cease concerning him,” it is largely because Zoram is bound by an oath.17 “An oath or promise of a Knight, is of all oaths and promises,” one Masonic monitor states, “the most inviolable and binding.” It goes on to explain that “Knights taken in battle engaged to come of their own accord to prison, whenever it was required by their captors, and on their word of honor they were allowed liberty for the time, and no one ever doubted that they would fulfil their engagements.”18 As a junior-ranking Christian Knight, Zoram’s word is his bond.

The story of Nephi, his two brothers, Laman and Lemuel, and their altercation with Laban so closely parallels the story of the Knights of the Red Cross (in Webb’s Masonic monitor, in particular) that it may be more than mere homology. The Red Cross Degree is based on the biblical story of the return of the Jewish exiles to the Holy City under the tutelage of “Captain” Zerubabbel. Nephi and his brothers “go down to the land of [their] inheritance” to gather their gold and silver and “precious things.”19 This could allude to the “vessels also of gold and silver of the house of God, which Nebuchadnezzar took out of the temple that was in Jerusalem,” or the search of the “king’s treasure-house” and the return of all confiscated Jewish relics at the behest of the Persian conqueror, Cyrus. It might be argued that the Book of Mormon story comes straight out of the Bible were it not for the presence of so many apocryphal tropes that are also in Webb. Perhaps the Book of Mormon merely takes its cue from Josephus, Webb’s inspiration, too. In his Freemason’s Monitor, Webb writes: “Darius, while he was yet a private man, made a vow to God, that if ever he came to the throne, he would send all the holy vessels that were at Babylon back again to Jerusalem.”20 This ostensibly imaginative reconstruction is in Josephus’ Antiquity of the Jews.21 In Webb, another fanciful tale appears that is also in Josephus, the story of how Zerubabbel beguiled Darius to keep his vow and return “the holy vessels remaining in his possession” to their rightful owners. The artifice of Nephi in the face of Laban’s recalcitrance seems patterned roughly after the apocryphal story of Zerubabbel and Darius. Smith certainly had access to The Antiquity of the Jews, as there was a copy in the Manchester library (near his home) a decade or more before the Book of Mormon appeared. As I have suggested, however, there is no reason to suppose that he read it; instead, he may have got the skinny on the book through conversing with someone who had.

That said, the Book of Mormon contains extrapolations that are unique to Webb and not found in either Josephus or the Old Testament. For example, in Webb’s account, the construction of the walls of the city of Jerusalem is interrupted briefly by an Arabian force. This Persian guard in medieval Saracen garb threatens to stop construction by slaying any and all (stone) masons, thus bringing to an end the restoration of God’s people. Fearful for their lives, they hide “in the lower places behind the wall” but are told, “Be not afraid … remember the Lord, which is great and terrible.”22 “Then Darius the king,” it says, “made a decree, and search was made in the house of the rolls, where the treasures were laid up in Babylon.” One may compare this to the story of Nephi’s brothers outside the walls of the city, hiding in the cavity of a rock lest they be detected and murdered by an avenging (Saracen) army, given angelic words of encouragement, and so on. A more detailed account in Thomas Sargant’s The Royal Arch Companion says that “three Sojourners” traveled to Jerusalem on a quest to discover their genealogy. Reading it, they delight in the discovery that they descend from noble stock. Excavating near the temple, they discover a vault. “All being equally anxious who should descend, they cast lots; the lot fell upon———.”23 They discover a “scroll” but, because of the darkness, are “unable to read its contents” (p. 89).

Is this not the gist of the Book of Mormon story? Three sojourners are named—Laman, Lemuel and Nephi—who “consult one with another; and … cast lots,” it says, “which of [them] should go in unto the house of Laban. And it came to pass that the lot fell upon Laman.”24 But poor Laman is not quite up to the task (making a hasty retreat the first sign of trouble), and so the job falls to Nephi. There seems no option left but to murder Laban and steal his armor (all done according to Templar custom). Beating a path to the “treasury,” Nephi makes his descent into its vault and recovers the brass plates—the Torah, it turns out (an allusion to the scroll in the Royal Arch story?), which cannot be read (an allusion to Smith’s reading disability?) without the aid of supernatural intervention.

Laban’s character, as I have said, seems patterned after that of the “Tiler,” an officer of the lodge with one specific calling: “to guard against the approach of cowans and eavesdroppers.” At the installation of the Tiler, “a sword is placed in [his] hands” so that he might “admonish the Brethren to set a guard over their thoughts … a sentinel over their actions, thereby preventing the approach of every unworthy thought or deed.”25 In fact, the Tiler’s concave, where “the ornaments, furniture, jewels and other regalia are deposited” (including the Ark of the Covenant), is also called the “treasury” (pp. 48–49). Nephi and his brothers can be seen or misconstrued (in Laban’s case) as “cowans and eavesdroppers,” too. That their uncle dispatches an armed guard to kill them for merely asking for what is rightfully theirs—the brass plates—is not simply heavy-handed but an overly literal interpretation of the Tiler’s role as protector of the lodge. Nephi impersonates Laban in order to gain entrance not simply to some vault but to the lodge—which may say something about the lengths to which Smith had to go to gain access to the mysteries of Masonry. While it is tempting to suppose that Nephi breaks into Laban’s house, a lodge break-in of the Royal Arch kind (descent into the vault where the plates of Enoch and scriptures are stored) may be something (Masonic) readers do not need to have spelled out for them. The theft, not unlike Laban’s killing, is a necessary evil. Payback for William Morgan’s murder may explain why Nephi is commanded to murder his uncle in cold blood.

Other Masonic furnishings ought to catch our eye, such as a compass that magically appears outside Lehi’s tent one morning, the so-called liahona.26 This will guide Lehi and his family (and another family, composed entirely of girls, that they adopt and take with them out of necessity) on the journey to the promised land. The liahona is a compass, but not in any orthodox Masonic sense. The Masonic compass is an open protractor, not a set of spiritually magnetized needles suspended inside a brass ball that might be said to point due west—but only so long as everyone behaves. Another type of compass in the Book of Mormon does fit the description of the Masonic variety, however. In early Masonic rituals, the compasses (plural) are the property of the Master alone and symbolic of the sun. As Clegg explains, this Masonic compass “is more usually applied to the magnetic needle and circular dial or card of the mariner from which he directs his course over the seas … when seeking his destination across unknown territory.”27 Liahona may also be a corrupt spelling or metathesis of Elion, one of the secret names for God in the esoteric Masonic tradition (2:695).

FIGURE 35a Arnold Friberg, Lehi Discovers the Liahona

The Book of Mormon, large ed. (1957; reprint, Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1966)

HAVING SAID ALL THIS, the Book of Mormon account is no mere plagiarism based on contemporary Masonic sources or events; it is as distinct from Webb as Webb is from Josephus and Josephus is from the Old Testament—although the parallels are striking and provide us with an important clue to the narrative’s overarching Masonic or Templar agenda, whether it is a lineal descendant or not. The Royal Arch quest for lost scripture, taking place in the wake of desolation and followed by the restoration of the people of God and rebuilding of the holy city, will be told and retold. The Book of Mormon is a very long book, the original edition numbering almost six hundred pages. That it tends to be on the sleepy side may not be due to its copious use of the Bible but instead to a highly nuanced and progressive unveiling of its own unique Masonic agenda, the quest for the long-lost book and all that entails being a means to some greater, post-Masonic end. The Book of Mormon embellishes, indeed spins its own yarn, using but a single motif: the quest for the long-lost book of all the Law.

FIGURE 35b The Order of the Gold- and Rose-Croix

Erich J. Lindner, The Royal Art Illustrated (Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1976), p. 167.

Lehi and his family travel to the promised land and complete the Masonic cycle. Nephi dies, and not long afterward it is time, once again, for a pilgrimage to the holy city in quest of some lost record of a once-great people. The Book of Mosiah picks up where the books of Nephi leave off. A full account of Mosiah’s tenure as Nephite philosopher-king is preempted by a tale of woe, the so-called Record of Zeniff, which recounts the exploits of a party of Nephite dissenters living among their Lamanite brethren to the north in the land of Nephi-Lehi (the land to the south and Zarahemla are the abode of the Nephites). The location may indicate an unconscious aversion on the part of the author for the north, but the intention may not be simply to disrespect Canada (as has been the American custom and vice versa).28 Rather, as Oliver explains in his Masonic handbook entitled The Book of the Lodge, “Masonically … the north [is] a place of darkness.”29

The people of Zeniff have given themselves over to a wicked king, the enigmatic “wicked King Noah,” and eventually to a Lamanite potentate. (The Book of Mormon seems to slander the biblical Noah; however, the bone it has to pick may be with his Masonic or Noachite priestly descendants—a distinction that is easily lost in the shuffle. The allusion may be Masonic, not biblical, a clever polemic attacking the moral bankruptcy of the Masonic establishment of antebellum New York.) Meanwhile, Mosiah sends sixteen strong men, led by Ammon, to inquire after the safety of the Nephite dissenters. They are under house arrest, prisoners in their own city, their leader, Limhi, reduced to gatekeeper and publican against his will. Ammon takes three men with him in an attempt to sneak past the sentinels at the entrance of the city but is accosted outside the city’s walls and thrown in prison. Not to worry: the story has a happy ending, with Ammon liberated and then liberator.

Limhi can be seen as in the type of Laban, but he does not follow Laban’s example. Ammon’s character seems patterned after that of the archetypical Nephi. Laban and Limhi are both gatekeepers. Both own sacred histories written on metal plates. Nephi and Ammon are both sent to recover such records. In both instances, an altercation takes place outside the walls of some great city, involving three voyagers on a quest to liberate humankind. But the two stories end very differently. Limhi complies, happily handing his copy of “the plates which contained the record of his people from the time they left the land of Zarahemla” over to his cousin, Ammon.30 He even gives Ammon a second genealogy, that of a lost people written on twenty-four gold plates, also in his possession. The people of Limhi will mount a successful escape, we are told, plying their Lamanite guards with wine and then slipping past them out “the back side of the city” (p. 201). Intoxication, it will be recalled, was the key to Nephi’s success and Laban’s undoing, too.

The substance and origin of the twenty-four plates cannot be known right away, requiring the linguistic expertise of a prophet—Mosiah, in this case. Ammon defers to the Nephite High Priest Mosiah, who is qualified as a “seer,” to make such secret things manifest “and hidden things … come to light” (p. 173). The voyagers in the Royal Arch story are “requested to read the … plate of pure gold, on which were certain letters forming words, which [they] humbly conceived to be the Sacred Word itself,” but they “refused, stating that according to Jewish law, it was not lawful for anyone to pronounce the Sacred and Mysterious Name of the Most High, excepting the High Priest, and then only once in the year, when he stood before the Ark of the Covenant to make propitiation for the sins of Israel.”31 To be sure, Ammon has his own compelling reasons to exercise discretion, for he is not a seer. Later, Mosiah informs us that the twenty-four gold plates are the last will and testament of the Jaredites. Moroni will later publish them as the Book of Ether.

Limhi explains to Ammon that a search party of his own, sent to Zarahemla to get help, inadvertently journeyed to a “land which was covered with bones of men, and of beasts, &c., and was also covered with ruins of buildings of every kind; having discovered a land which had been peopled with a people, which were as numerous as the hosts of Israel.”32 It is a scene worthy of the Royal Arch and its condemnation of ancient Israel. “You have now witnessed the mournful desolation of Zion,” it says, “the sack and destruction of the city and Temple of our God, and the utter loss, as the world supposed, of all those articles contained in the Holy of Holies.”33 Limhi’s scouts return with “breast-plates” and “swords,” too, whose “hilts thereof hath perished,”34 alluding to the carnage at Jerusalem some eighteen centuries later—the genocide of the Knights Templar by a superior and entrenched Saracen army during the Crusades.

Ammon leads Limhi and the people of Zeniff back to Zarahemla (the Jerusalem of the New World). They must traverse rugged terrain under cover of night, a Babylonian-like flight and veiled, Royal Arch journey to Jerusalem. The story of the reclamation of the people of Zeniff has all the makings, at least, of a reified Royal Arch journey on a mass scale. “But you have seen those afflicted sons of Zion visited, in the darkest night of their adversity, by a peaceful light from heaven,” Sargant’s monitor proclaims, “which guided them over rough and rugged roads to the scene of their former glory.” The Record of Zeniff can be seen, then, as a Babylonian-like incursion set in America, told from a Royal Arch point of view, promising God’s chosen people in the New World the same sense of national, cultural, and religious renewal extended to the ancient Israelites. “You have seen them enabled, by the signet of eternal truth,” the monitor goes on to explain, “to pass the veils that interposed between them and their fondest hopes.”35 The people of Zeniff bring back with them all their gold and silver and their precious things—an allusion to the holy vessels of the temple returned to the Jews at the behest of the Persian kings, Cyrus and Darius. Their reclamation sets the stage for the restoration of the power and authority of the priesthood on the American continent by a priest of the order of Melchizedek, whose shoe latchet neither Mosiah nor Nephi are worthy to loose.

Several clues appear in the Zeniffite record, in particular its account of the life and death of Nephite prophet of woe Abinadi, cast into prison and put to death on a trumped-up charge of “revil[ing] the king.” The king’s name, Noah, may allude to the Noachian emblems of the Master Mason Degree—ark and anchor symbols of hope and rest in a “tempestuous sea of troubles.”36 The true Master Mason, as the certificate suggests, should be an island of virtue, towering above the waves of immorality that crash all around him. Abinadi’s insolence can also be seen as that of a Master Mason exercising his prerogative “to correct the errors and irregularities of … uninformed brethren, and to guard … against a breach of fidelity.” He means Noah’s office or his court no discourtesy. “To preserve the reputation of the fraternity unsullied,” the Charge to Master Masons at the initiation into the Third Degree continues, “must be your constant care…. Let no motive, therefore, make you swerve from your duty, violate your vows, or betray your trust; but be true and faithful, and imitate the example of that celebrated artist whom you this evening represent” (p. 72).

Hiram Abiff is that celebrated artist whom Abinadi represents. Refusing to “recall all his words,”37 even at the behest of the king and in the face of certain death, Abinadi allows himself to be tortured to death as a final act of piety. His dying words, “O God, receive my soul,” allude to the Bible and to the grand sign and call of distress of the Master Mason, “O Lord! my God!”38 However, Abinadi’s skin is scourged with faggots, which is not how Hiram Abiff died. The manner of Abinadi’s death recalls that of the servants of God whom Nebuchadnezzar threw into a fiery furnace for insolence. They, however, are untouched, whereas poor Abinadi succumbs. And although he is a Christ figure of some kind, his death is not very Christ-like.

In fact, a strong case can be made for Abinadi’s death as patterned after that of the Templar High Priest in Masonic lore, Grand Master Jacques de Molai, by the wicked king of France, Philip IV. The martyrdom of De Molai marks the dissolution of the so-called Order of the Temple, a period of spiritual darkness that forced the Templars underground. De Molai and his Knights Templar, according to legend, were imprisoned, tortured, and then “burned to death upon fagots.”39 De Molai’s last words before the papal commission of Paris around 1309 underscore his unflinching belief in “but one God, one faith, one baptism, one Church, and when the soul is separated from the body … but one Judge of the good and evil” (p. 781). Abinadi also expounds the one, true Christian faith, the unity of the Father and Son, and, finally, death, resurrection, and judgment at the hands of that great Judge.40

FIGURE 36 The Great Eclipse and Terrible War About to be Made in His Name

Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John D. Yorston, 1911), 5:106b.

Webb’s Monitor contains an account of the Templars’ betrayal at the hands of wicked king Philip. Philip, it says, offered the papacy to the “greedy” archbishop of Bordeaux “on his engaging to perform six conditions,” the sixth revealed to him after making an oath.41 False charges brought against the Templars led to their disenfranchisement and a great many executions. Although the charge of treason (Abinadi’s crime, too) was subsequently shown to be baseless, “the Templars … thus declared innocent” (p. 184) were no more. The order never recovered.

One wonders whether the story of Abinadi’s martyrdom is not also veiled commentary on Morgan’s kidnapping and murder by rogue Canandaigua Masons in 1826. Not unlike Abinadi, Morgan refused to recant all his words, paying the ultimate price. Does the Book of Mormon speculate that Masons cremated Morgan’s body in order to destroy the evidence? Is Alma’s secret assembly of saints, which follows on the heels of Abinadi’s murder, the pattern and rationale for Smith’s own Templar-style Masonic revitalization movement? One thing is clear. Abinadi’s martyrdom and Alma’s church in the wilderness look forward to the arrival of a full-fledged and decidedly Christian Masonry in America. At this point, all the reader can do, like Masonry itself, is wait.