“Does not Joe Smith profess to be Jesus Christ?” No, but he professes to be His brother, as all other Saints have done and now do: Matt. xii:49,50, “And He stretched forth His hand toward His disciples and said, Behold my mother and my brethren; for whosoever shall do the will of my Father which is in heaven, the same is my brother, and sister, and mother.”

IN THE PROTR ACTED ACCOUNT of the quest for the long-lost book and all that search entails, the books of Alma and Helaman pick up where Mosiah leaves off. They contain much vital information of a social and cultural (even theological) kind but are not nearly as important as what precedes and what follows. In excess of two hundred pages, these two books do a masterful job of killing time (five hundred years or more) as we await the advent of something entirely different. In the meantime, Nephites and Lamanites duke it out. What began as a sibling rivalry engulfs an entire continent, escalating into a race war that pits white against dark in a battle to the death. There is much gratuitous swordplay, and the level of testosterone very high, indeed. The men of renown—all the Mosiahs, their sons, the Almas and their sons, even the Helamans (of which there are more than one) and theirs—are manly men: loving fathers and obedient sons, virtuous husbands, able statesmen, honorable soldiers for Christ on the field of battle, quick to forgive their enemies, ever mindful of the poor, the widow, etc., etc. The protracted battle for cultural supremacy between the Nephites and Lamanites in Alma and Helaman can be seen as a Templar-like battle to the death. But these books also prepare the ground in a near-literal sense for something truly glorious: the appearance of the resurrected Christ in the book of 3 Nephi.

From a Masonic point of view, 3 Nephi is clearly the crux of the matter, a turning point in the narrative, when Mormonism veers far from Masonry without necessarily closing the gap with orthodox Christianity. On one level, the visit of Jesus to the Nephites following his death and resurrection can be seen as an orthodox affirmation of his divinity. Robert N. Hullinger contends that such testimony locates Smith opposite skepticism, that “the Book of Mormon was an apologetic for Jesus Christ,”1 but this may not be the intention at all; the Christocentrism of the Book of Mormon may rather be a means to an end. Rather than a defense of Jesus’ divinity, the Book of Mormon uses the appearance of the resurrected Christ to the Nephites to formulate an apology for Christian Masonry as the logical fulfillment of all that passes for Masonry up to this time—both in the narrative and in the history of the movement in the century leading up to Smith’s appearance. The hope of both text and author is to mend the rift that divides Ancients, or Royal Arch Masons, and their orthodox counterparts, dubbed Moderns but calling themselves Craft Masons. The plethora of French, German, and even Russian Royal Arch lodges that are partial to the Scottish Rite (remember that the titular head of the higher degrees, Chevalier Ramsay, was a Scot) need not concern us. All can be seen as variations on a Royal Arch/Knights Templar theme (allowing for a degree of poetic regional license), even the Rosicrucians, essentially the snobs of the movement, consisted largely of Royal Arch Past Masters who felt they were the only true Masons and the so-called Egyptian Rite—which included women and dabbled in the occult—also comes by way of the Royal Arch.2 But to see Mormonism as simply one of these variants of the Royal Arch will not do, for this ignores the more important fact that it hoped to graft all the branches to a single trunk—to the cross of the Mormon-Masonic Christ, to be precise. In order to do so, the overarching supremacy of the Christian or Chivalric Degrees because of their preoccupation with the Crusades and knighthood had to be established, making Mormonism both root and branch and thus the solution to the problem of (Masonic) sectarian fragmentation and strife. A dispensation from heaven gives it the necessary power to effect this radical change for the better—or so the Book of Mormon and its author would like us to believe.

That most of what Jesus has to say comes straight out of the King James Version has always struck critics as extremely problematic from a purely source-critical standpoint. This is unimportant when compared to the literary function such glosses serve, shifting the focus from the Old Testament to the New. Suddenly, the Book of Mormon is decidedly Christian, more or less in keeping with the orthodox belief in the fulfilment of the Law by Christ. All of this can be interpreted as a fulfilment of orthodox Masonry (which considers itself a Jewish faith, taking for its inspiration the Old Testament and the patriarchs) and even of the Royal Arch, which is no less Judaic in tone, which are supplanted by the Christian Degrees (the Knights Templar simply one of several Knightly designations listed). Given the Book of Mormon’s ambition to represent the stratosphere of the Masonic ritual system, it is perhaps appropriate that in it the resurrected Christ descends from the heavens, bringing the Saints, along with himself, down to earth, where he gives them his blessing.

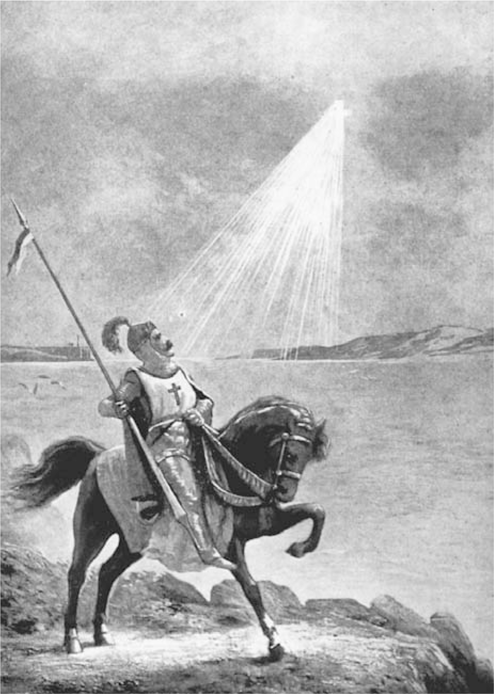

FIGURE 37a The Sign in Heaven of the Knights Templar

Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John D. Yorston, 1911), 5:194b

For the more orthodox Masonic reader, this is a hard pill to swallow. That the Book of Mormon might be said to credit the Christian Degrees as the fulfilment of prophecy constitutes a bold departure, indeed. As Mackey explains, Christian Masonry threatened to do away with everything that preceded it. “The great discovery which was made in the Royal Arch,” he writes, “ceases to be of value in this degree; for it, another is substituted of more Christian application…. Everything, in short, about the degree is Christian.”3 Not unlike the Christian claim of fulfilling the Law of Moses rather than doing away with it, so, too, the argument for the supremacy of the Christian Degrees must be seen as the basis for a completely new patriarchal order of things.

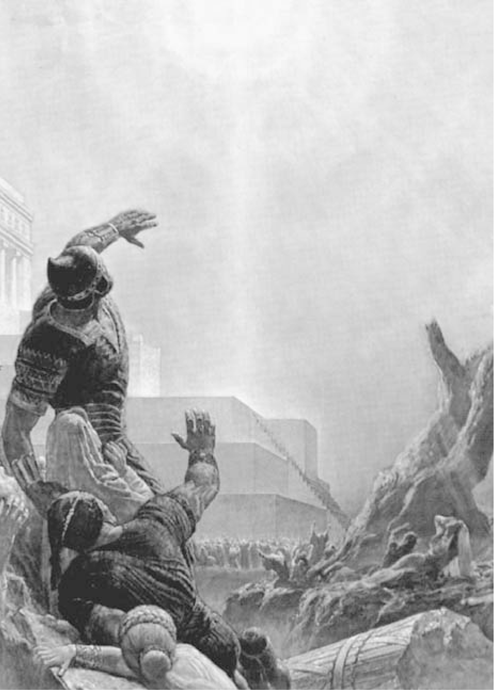

FIGURE 37b Arnold Friberg, The Appearance of Jesus to the Nephites

The Book of Mormon, large ed. (1957; reprint, Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1966)

Smith’s journey from village seer to prophet of God can thus be seen as both a departure and a mere taking of Masonry to its logical conclusion, climbing the Masonic mystical ladder to its highest level, Mormonism being the most Christian of the Masonic Degrees yet. When the Nephite Christ says his good-byes, his last words are telling: “And my Father sent me that I might be lifted up upon the cross; and after that … I might draw all men unto me, even so should men be lifted up by the Father…. Therefore if ye do these things, blessed are ye, for ye shall be lifted up at the last day.”4 In light of allusions in the text and paraphrases of the Knights Templar initiation ritual, the elevation of Masonry to the status of a bona fide Christian fraternity is the objective.

The appearance of the resurrected Christ is preceded by what might be termed a Masonic raising of the American continent herself. There are great tempests and earthquakes, buildings “falling to the earth” and cities “sink[ing] into the depths of the sea.” The earth falls under a blanket of thick darkness (pp. 470–472). There is a brief silence, and then “a small voice” is heard—as though the Father of Heaven is whispering to Mother Earth some Grand Omnific Word? It is light again. Jesus makes his New World debut, descending to earth “clothed in a white robe” (p. 476). Were this biblical allusion, he would be clothed in red not white—the garment of the biblical Christ dipped in blood.5 The Book of Mormon dresses him in the white robe of a Knight Templar, for he comes to make Knights Templar of his devoted followers. He motions to the people to “arise” and thrust their hands in his side and feel the prints of the nails in his feet. Those who do so are not doubting Thomases. All such doubt has been eradicated in the cataclysm that precedes his arrival. His appearance, after all, is a coronation and a knighting.

In the Knights of Malta Degree (another of the Christian or Chivalric Degrees), three New Testament passages are read: Acts 28:1–6 (the story of Paul’s miraculous escape, first from being buried in the sea and then from falling down dead from a snakebite), John 19:19 (the title given Christ by Pilate, “Jesus of Nazareth, the king of the Jews”), and last John 20:24–28 (the story of Thomas).6 The story of Jesus’ appearance to the Nephites begins with the no less miraculous escape of the Nephites from a raging sea and swelling landscape, followed by a no less titular but rather more flattering précis of Jesus’ true identity and finally a democratization of Thomas’s inspection of the stigmata. The last is called the “Sign of Unbelief,” the token of one’s reception into the order of the Knights of Malta. In the North American ritual, “the Sign of Unbelief is taken,” it says, “and is thus made: One brother says: ‘Reach hither thy finger and feel the prints of the nails.’ They join hands and force the f–- f–- into the centre of the palm. They say: ‘Reach hither thy finger and thrust it into my side.’ Each extends his l–- h–- and presses his fingers into the l–- s–- of the other. With arms thus crossed, one says: ‘My Lord.’ The other replies: ‘And my God.’”7

Jesus celebrates the coming of the New Jerusalem, in particular.8 This is precisely what one would expect a Christian Knight to do. In the Scottish Rite, the supplicant dons the white robe of apocalyptic Masonry and ponders the mysteries of the New Jerusalem.9 The Jewish capital’s best-known defenders, the Knights Templar, are Masonry’s oldest and most vocal champions of the holy city’s return to glory. The Nephite Christ proves no exception.

The risen Lord goes on to instruct the Nephites in the proper manner of baptism, discussing the issue of authority to baptize and criticizing infant immersion. A slight revision of his Sermon on the Mount appears, followed by an explication of the hidden meanings of the passages in John concerning the “lost sheep of Israel.” They are not Gentiles but the Lost Tribes. After blessing children, he breaks bread, blesses it, and gives it to the people in remembrance of his body. They take wine and drink, too, in remembrance of his blood. The next day he appoints twelve Nephite disciples, who demonstrate greater tenacity and thus faith than their Old World counterparts by not falling asleep when their Lord goes a little way off to pray to the Father. The Knights Templar “Exhortation” (seven ejaculations in all) might be said to be the pattern for Jesus’ appearance and ministry to the Nephites in the Book of Mormon:

1. Let the brother of low degree rejoice in that he is exalted.

2. Come unto me, all ye that labor, and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.

3. Christ suffered for us, leaving us an example that we should follow his steps.

4. For as we were as sheep going astray, but now are we returned to the shepherd and bishop of our souls.

ITEMS 5, 6, AND 7 merely paraphrase more of the Sermon on the Mount.10 The story of the Last Supper, Jesus’ disappointment in finding Peter and the two sons of Zebedee unable to watch him as he prays a little way off (Matthew 26:14–15, 36–39; 27:24–38), and the appointment of Matthias and thus a full complement of twelve apostles in the wake of Judas’s treachery and death (Acts 1:15–26) follow this (p. 190). The Knights of Malta Degree, in fact, very nearly accounts for Jesus’ every word and deed in the Book of Mormon, making the book a veiled mass Masonic raising of considerable importance in the grand Masonic and teleological scheme of things.

Understanding the Book of Mormon as fictive Masonic ritual and apology for Christian Masonry vis-à-vis the appearance of Jesus Christ and his elevation of righteous Nephites and Lamanites to the same order of Christian Knighthood as himself, Mormonism thus forming a New World Masonic theocracy, changes rather significantly our understanding of the nature, origin, rise, and development of this religious community. Early Mormonism veered far from orthodox Masonry and orthodox Christianity in one fell swoop: too Christian to be Masonic, too Masonic to be Christian. (As an aside, although polygamy was a sore point for American Protestants, locating Mormonism on the cultural and social periphery of Evangelical, middle-class society, it also kept orthodox Masonry at bay.)

That early Mormonism had a primitivist Masonic agenda has been forgotten over time, the religion keeping its ties to Masonry such a well-guarded secret that, given enough time, the faith would become vulnerable to any thoroughgoing Christian revisionism, having gone on to become a Christian denomination. The emphasis in the early years on the Bible and not the Book of Mormon, for example, has undoubtedly played a role in the steady Protestantization of modern Mormonism. Mormon missionaries are barely distinguishable from their Evangelical counterparts, dressing themselves and their beliefs in corporate garb, toting the same (by all appearances) zippered set of scriptures and testifying with equal zeal to the divinity of “Christ and him crucified.” For a time, Mormons appeared to be in the business of handing out free copies of the New Testament, the Book of Mormon relegated to a special order item.

A host of superb scholarly minds could not agree more. Early Mormons were largely conservative, Bible-believing Christians: the Bible rather than the Book of Mormon informed them on matters of belief and practice. The Book of Mormon did not mold their thinking in significant ways until later in the history of the movement. The personal testimonies of many early converts have an orthodox, Fundamentalist ring.11 The new faith constituted a radical but essentially Protestant alternative to Evangelicalism—in the beginning, anyway, before polygamy and the political kingdom of God took it beyond the pale of Christianity.12 Periodical literature, sermons, and private journals seem to support this. Mormon historian Philip Barlow makes the strongest case for the centrality of the Bible in early Mormon life and thought. “Although [Joseph Smith] described the Book of Mormon as more correct than any other book,” he writes, “there is little evidence that he ever took the time to study its contents as he did the Bible’s.” The Book of Mormon “did not become the basis for early Church doctrine and practice,” he contends.13

In his 1977 doctoral dissertation, Gordon D. Pollock underscores Mormonism’s attempt to revitalize Christianity. Mormonism’s first critics and apostates criticized Smith for creating “a religion which veered far from Christianity.”14 That testimony has largely gone unchallenged. Jan Shipps has developed this idea most fully in her book, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition. She explains that “the Latter-day Saints … embarked on a path that led to developments that now distinguish their tradition from the Christian tradition as surely as Christianity was distinguished from its Hebraic context.” Mormonism, like early Christianity, evolved into “a separate religious tradition and … must be understood and respected on its own terms.”15 Both Pollock and Shipps emphasize that Smith’s first religious musings were in line with those of orthodox Protestant theology. Later on, though, as his thinking “matured,” he gravitated to the arcane and heretical. An avalanche of scholarship since then seems only to support this.

The publication of William E. McLellin’s papers, edited by Jan Shipps and John Welch, makes the same point: McLellin’s preoccupation with biblical proofs and images was an example of early Mormon Protestant sensibility. Welch likens McLellin’s journals to the letters of Paul in the New Testament, whereas Shipps offers the documents as proof of early Mormonism’s rootedness in Christianity.16 Pollock points out: “When all is said and done, however, we did not need McLellin’s journals to know this. The same information may be found in Reynold Cahoon’s 1831 journal. John S. Carter also makes these points in his journal that extends from 1831 to 1833.”17 Early Mormons, so named because of their belief in the Book of Mormon, did not much care for the book, one presumes.

Evangelical scholars seem much more forgiving, locating early Mormonism on the lunatic fringe of antebellum Protestantism, a rural Revivalism to the left of Baptists and Methodists.18 Its extremely sardonic attacks against the Protestant mainstream, notwithstanding—the Edwardsean Evangelical establishment and its Finneyite counterpart, in particular19—enough latitude exists to include Mormonism as a full-fledged member of rural Protestantism’s loose coalition of dissenters and radical democrats. Antebellum America’s most notorious and obnoxious Evangelical backbenchers, early Mormons were Christians whether they wished to be viewed as such or not.

That said, we dare not ignore the fact that Mormonism rejects any such connection to contemporary Christianity. The disproportionate number of biblical references in the early sources—in Smith’s recorded sermons, in particular—can be explained very easily without discarding the Book of Mormon or divorcing it from early Mormonism. That the first Mormon missionaries defended the new faith on solid biblical grounds is neither surprising nor paradoxical when one considers their audience: largely Bible-believing Christians and/or Evangelical critics. Orson Pratt, early Mormonism’s premier apologist for polygamy, took pride in his knowledge of the Bible, which merely allowed him to defeat his monogamist enemies using their scriptures.20

There is an equally important theological consideration, too. In Mormonism, the Bible (or stick of Judah) and Book of Mormon (or stick of Joseph) are “one.”21 Brigham Young taught: “There is no clash in the principles revealed in the Bible [and] the Book of Mormon…. The Book of Mormon declares that the Bible is true, and it proves it; and the two prove each other true.”22 The Book of Mormon claims to restore those plain and precious passages in the Bible that were either lost or removed by corrupt scribes. To argue that Mormons chose the Bible over the Book of Mormon ignores a fundamental hermeneutical and theological principle of Mormonism: the elucidation of biblical texts by means of additional revelation. Thus Mormons like William McLellin read their Bibles in earnest, to be sure, but through the lens of the Book of Mormon and other modern-day revelations.23 This clearly set them apart from the Protestant mainstream. They may have been Christians, but they did not consider themselves to be like other Christians, and we should perhaps take them at their word. The Masonic connection merely drives home that point.

Despite the fact that Richard Bushman argues brilliantly for the primacy of the Book of Mormon,24 there may be some truth to the argument that it had a very brief shelf life. However, this may not have been because early Mormons preferred their Bibles over their Books of Mormon but rather because the temple loomed largest of all—and for good reason. A Masonic reading of the Book of Mormon suggests that it was meant as a fraternal Ark of the Covenant and thus temporary literary abode of Masonry (in the wake of the Morgan affair) until more permanent and spacious surroundings could be erected. The Bible had an important role to play in public displays of faith at home and abroad, but the Book of Mormon, enshrined in the temple ritual, was the Mormon Holy of Holies. There is little wonder that Mormons did not consult it. That their High Priests chose not to as well is the problem, for as the Bible replaced the Book of Mormon as the locus of faith, the temple—and religion, too—became a bastion of exclusivity rather than a monument to inclusion.