THE ECONOMIC KINGDOM OF GOD: MASONIC UTOPIANISM UNVEILED

“Do the Mormons believe in having all things in common?” No.

We are all a little wild here with numberless projects of social reform. Not a reading man but has a draft of a New Community in his waistcoat pocket.

THE MORMON PROPHET had deep waistcoat pockets, indeed. None of his “new communities,” however, not even those founded on the Law of Consecration and Stewardship (also known as the United Order and/or the Order of Enoch), was truly radical: they were neither early Marxist collectives nor had much in common with the systems favored by contemporary socialists such as the Shakers and the Oneidan Perfectionists. In fact, Smith’s economics, every step along the way, toed the Jacksonian line of rugged self-reliance and dogged determination, as well adhering to the essentially conservative theorizing of contemporaries such as John L. O’Sullivan. O’Sullivan attacked artificial distinctions only, defending the fruits of hard work and thrift, and thus natural distinctions, as perfectly consistent with the Republican ideal of a “classless society.”1 Brown University social scientist Lester Ward, a disciple of O’Sullivan, thought that “fraternalism” rather than “competition” allowed individuals to have their cake without taking food out of the mouths of the poor. What he called the principle of “Sociocracy” gave credence to a measure of natural inequality, the real bugaboo in American society being the existence of too many “artificial inequalities.”2 And what was the role of government in all of this? The less the better, of course, the judicious regulation of modern science holding up the rear.

Let us not be swayed by Mormonism’s enemies, who unfairly accused the Saints of such economic evils as pooling their resources in order to prosper collectively and individually. These were the sour grapes of locals in Kirtland, Ohio, Jackson County, Missouri, and Nauvoo, Illinois, making a mountain out of a molehill. Early Mormonism’s rapid growth and collective wealth may have been the consequence of a divinely regulated cooperative scheme, but the faith was not quite communistic. The individual not only had some say but owned shares; there was very little in the way of an enforced radical community of goods. “For not only did Joseph Smith succeed in reconciling contrarieties then animating the little flock in Kirtland,” Thomas O’Dea observed long ago, “he also brought together in a single social pattern two important tendencies in the behavior of western America: hardy, self-reliant individualism and the friendly urge toward mutual helpfulness.”3 Leonard J. Arrington’s seminal Great Basin Kingdom cautions against a crude conflict interpretation, too, having this to say:

One is tempted to conclude that, while the Mormons boasted of being a “peculiar people,” their economic program was definitely “unpeculiar” in the America of its birth. Central Planning, organized cooperation, and the partial socialization of investment implicit in Mormon theory would seem to have been a part of the democratic theory of the Founding Fathers. Unquestionably, traditional American thought and practice sanctioned the positive use of public agencies to attain given group objectives, and this was, of course, the Mormon formula.

ARRINGTON OPINES that “communitarianism” was a “sister movement” that drew its inspiration “from the same sources.” But in the West, “Mormon institutions [were] the more typically early American, and the individualistic institutions of other Westerners … the more divergent.” He continues: “It may yet be conceded that the well-publicized conflicts and differences between Mormons and other Westerners and Americans were not so much a matter of plural marriage and other reprehensible peculiarities and superstitions as of the conflicting economic patterns of two generations of Americans, one of which was fashioned after the communitarian concepts of the age of Jackson, and the other of which was shaped by the dream of bonanza and the individual sentiments of the age of laissez faire.”4 Arrington’s notion that conflict arose because of a kind of economic generation gap is compelling.

Mormonism’s critics were wrong to accuse it of dreary war communism. The real problem lay in a concerted attempt to achieve greater balance between the needs of the individual and those of the larger community. Hardcore individualists and uncompromising communitarians drifted in and out of the church, unable to abide such a balanced approach.5 John Corrill (an ardent liberal) and Alpheus Cutler (the radical communitarian) joined and then left because, for the one, it was too communal and, for the other, too liberal. What first attracted adherents and drove them away were not too many or too few concessions to laissez-faire but a consistent Jacksonianism that seemed too good to be true, far too competitive and cooperative to be democratic.

Ironically, the Book of Mormon does not figure in any of this; rather, it seems to defend a radical communitarianism that ends in failure, the Nephites lacking the will to live according to higher economic laws. Economic historians of Arrington’s stature, however, have a friend in the Book of Mormon, a defense of classic Jacksonian economic theory in keeping with the general Masonic understanding of such things. Whether in the Northeast, Southwest, or the wild, wild West, Mormonism represented an overly traditional, indeed classic early American economic system that seemed ill suited to the emergent modern world of naked competition and a purely market-driven economy. Neither did the move southward and then westward do much to increase Mormonism’s chances of acceptance. The encroaching transcontinental railroad made sure of this.

The Book of Mormon does not favor radical community of goods or even suggest that socialist utopian dreams really can come true during the millennium. Even the utopian society that Jesus establishes among the Nephites is not quite what it seems. “And they had all things common among them,” the book says, “therefore there were not rich and poor, bond and free.”6 They are eventually destroyed by the Lamanites because they “have their goods and substance no more common among them, and they began to be divided into classes, and they began to build up churches unto themselves, to get gain, and began to deny the true church of Christ” (p. 516). Hansen is quite right to suggest that “the Book of Mormon … describe[s] the Nephites as living in ideal Christian communities, with no poor among them.”7 It does not necessarily follow, however, that the Book of Mormon ideal simply proved too lofty for both Nephites and Latter-day Saints. Especially problematic is the argument that Mormons rejected “the Jacksonian doctrine of equality of opportunity in favor of the more radical principle of equality of condition,” in part because of the Book of Mormon, but “it was soon obvious to the prophet that the realization of such ideals would have to be deferred until the Saints had removed themselves from the world, both physically and spiritually” (pp. 126–127). Neither the Book of Mormon nor Mormonism’s early communities in Ohio and then Missouri and Illinois constitute a case that Mormon economics represented a radical departure from the Jacksonian norm.

Without doubt, the first Mormon settlements seemed to favor the communal holding of goods, which neighbors thought suspiciously un-American. The community-of-goods ideal refers to both radical redistribution of wealth and conservative admonitions simply to care for the needy. Early Mormonism tended to favor an economic variant of the latter, perhaps overly hierarchical but nonetheless a system of Christian mutual aid in the main. As James M. Stayer points out in his book The German Peasants’ War and Anabaptist Community of Goods, the reference in the Book of Acts to the early church practice of having all things in common is open to more than one interpretation.8 Swiss Anabaptists thought it described a rule of sharing (within families) and thus an edict against exploitation. Moravians assumed that it prescribed a regimented economic equality.

Christian mutual aid, then, has allowed Mennonites and Mormons to reap a bounteous harvest without feeling obliged to give it away. Brigham Young’s estate, for example, was valued at a million dollars at the time of this death in 1877.9 Leadership had spiritual and material dividends, including special land allotments and seats on church-owned corporations. Quinn explains: “The greatest improvements in income and wealth came with service as the President of the Church, then as his counselors, then as the Presiding Bishop and Quorum of the Twelve, then as the counselors to the Presiding Bishop, and to the least degree, if at all, with service as Council of Seventy.”10 At present, the LDS Church is one of the richest (for its size) in the world, with an extensive investment portfolio that any of the larger American denominations would be proud to call its own.11 Its constituents in the United States are among the better-educated and financially well-off of the middle class. So long as they do not forget to look after the needs of the poor among them, Mormons have no need to fear any material prosperity that might come their way.

When Smith arrived in Kirtland to become acquainted with an entire congregation of radical, communitarian Campbellite converts, they soon discovered that their new religious head was no utopian socialist. The first order of church business amounted to the suspension of community of goods in favor of what Smith called “the Law of Consecration and Stewardship,” a “more perfect law of the Lord.”12 According to the Law of Consecration, church members are stewards rather than property owners. Private property is deeded to the church and then deeded back to its original owners, who are then free to add to it in any way they please. Any surplus, however, goes to the bishop, who in turn uses it to assist the poor and fund community construction projects. Early Mormon economic policy resolved to eradicate poverty without stifling the entrepreneurial spirit consistent with the American dream of economic, social, and political mobility that did not discriminate on the basis of class.

The market economy left to its own devices bred inequality and poverty, too. Were one to find a way to regulate the ill effects of the market without government getting involved, then the needs of rich and poor would be looked after equally. One of Smith’s early 1831 revelations explains:

Wherefore, hear my voice and follow me, and you shall be a free people, and ye shall have no laws but my laws when I come, for I am your lawgiver…. For what man among you having twelve sons … and saith unto the one: Be thou clothed in robes and sit thou here; and to the other: Be thou clothed in rags and sit thou there—and looketh upon his sons and saith I am just? Behold … I say unto you, be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine…. And if ye seek riches which it is the will of the Father to give unto you, ye shall be the richest of all people, for ye shall have the riches of eternity; and it must needs be that the riches of the earth are mine to give; but beware of pride, lest ye become as the Nephites of old.13

IDEALLY, MORMONISM would make aristocrats of all its citizens—who sported purple robes rather than a red flag. It appealed to the temporarily out of work, entrepreneurs down on their luck who were eager to reclaim their lost birthright. The revelation continues:

And I hold forth and deign to give unto you greater riches, even a land of promise, a land flowing with milk and honey, upon which there shall be no curse when the Lord cometh; And I will give it unto you for the land of your inheritance, if you seek it with all your hearts. And this shall be my covenant with you, ye shall have it for the land of your inheritance, and for the inheritance of your children forever, while the earth shall stand, and ye shall possess it again in eternity, no more to pass away. But, verily I say unto you that in time ye shall have no king nor ruler, for I will be your king and watch over you.

(sect. 38:18–21)

Kirtland had been a providential detour on the road to Zion, which, according to revelation, was in Jackson Country, Missouri, not far from Independence. As Mormons bought up land and banded together to practice the Law of Consecration and Stewardship, Missourians in the neighborhood began to object and finally threatened civil war. Outnumbered, the Mormons were forced to give up their land and their experiment in economics in 1834. A lesser law, the Law of Tithing, took its place, a temporary proviso—so the argument goes—that required the Saints to pay one-tenth of their surplus to the church annually (sect. 119).

As Leonard Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean May explain in their book Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation among the Mormons, in principle the Law of Tithing was not a radical departure from the Law of Consecration.14 The Law of Consecration and Stewardship has never been reinstated because the Law of Tithing—revelations to the contrary notwithstanding—can be viewed as superior rather than inferior. The Law of Tithing simply meant that the Mormon economic kingdom had a much better chance of amassing the collective wealth it required if it allowed its membership to keep a bigger portion of their hard-earned money. The Law of Tithing struck a better balance of acquisition and cooperation than the Law of Consecration and Stewardship had. The Saints were admonished to be of one mind and heart, one in purpose—caring for the poor in their ranks but getting rich as quickly as possible, too.

Under Brigham Young, the Law of Consecration and Stewardship was reinstated. A few communalistic experiments (such as Orderville) came and went as a result. As a rule, however, economic association in pioneer Utah was of the joint-stock type. The Brigham City Cooperative (a joint-stock company and the brainchild of Lorenzo Snow) became the model for Young’s regionwide consumers’ cooperative system of 1868. Mormons were stockholders with a stake in local businesses and the larger economy. Arrington, Fox, and May explain that “virtually the entire town worked for the cooperative, the opening and closing of the departments were uniformly regulated by the ringing of a bell in the courthouse tower” (p. 117). Daily life in the Mormon village was a beehive of activity, productivity, uniformity, and solidarity.

The economic policies of the church under Heber J. Grant—in particular, his Church Security Plan, or Welfare System—were likewise of the joint-stock type. President of the LDS Church at the time of the Great Depression, Grant was critical of the New Deal, although he supported federal work-relief programs. He objected to the dole, making an exception for America’s worthy poor—the sick, aged, or disabled—who ought to receive charity. “Our primary purpose in organizing the Church Security Plan,” he reasoned in 1939, “was to set up a system under which the curse of idleness will be done away with, the evils of the dole abolished, and independence, industry, thrift, and self-respect be once more established among our people…. Work is to be re-enthroned as the ruling principle in the lives of our Church members.”15 For much of the Depression, the Mormon Church refused to accept federal assistance, gaining considerable public support because of its hardy self-reliance during such a difficult period in America’s history.

Ironically, some outsiders thought the Church Welfare System was communistic. J. Reuben Clark Jr., Grant’s second counselor, defended the church against the charge of harboring communist sympathies. In truth, some of its bishops were guilty as charged, seeing in the rise of communism a vestige of the United Order. As John R. Sillito and John S. McCormick have shown, Mormon bishops made up a large contingent of the Socialist Party in Utah.16 But Clark, an outspoken critic of Communism at home and abroad (as well as an apologist for the faith), was nonetheless quite correct when he insisted that Mormonism was and always had been the antithesis of communism. “There is a growing—I fear it is growing—sentiment that communism and the United Order are virtually the same thing,” Clark lamented, “communism being merely a forerunner, so to speak, of the reestablishment of the United Order.” He chastised bishops who “belong to communistic organizations [and] are preaching this doctrine,” using the Mormon scriptures to repudiate what he called “dead level equality.” Equality, Clark surmised, “will vary as much as the man’s circumstances, his family, his wants and needs, may vary.” The United Order, he pointed out, “was not a communal life, as the Prophet Joseph Smith, himself, said … but an individualistic system … built on the principle of private ownership of property.”17 Clark was careful not to mention the Book of Mormon, which he may have thought a contradiction.

In the Book of Mormon, the Nephites never practice anything like radical community of goods—even though they are said to have “all things in common.” The text explains precisely what it means by this, and it involves not radical community of goods but “every man dealing justly, one with another.” The only dead leveling in the Book of Mormon is of a spiritual kind. Passages that bespeak an equal distribution of wealth refer to “Heavenly gifts.”18 Nephites of various economic and social standings have the church, an abiding faith in the divinity of Jesus Christ, an equal superabundance of genuine and heartfelt love for one another, equal access to the spirit of God, and myriad gifts of the spirit. Mere economic equality pales in significance.

The utopian social order that Jesus inaugurates in the New World is a case in point. For roughly two centuries, a period of peace and prosperity ensues. The Nephites are universally virtuous. Government is essentially nonexistent. Even racial distinctions disappear. The people are of one race, one mind, one heart, one faith, dealing justly one with the other without any interference from the state. The church itself plays no significant role (at least not one that is easy to detect). Yet there are still rich and poor—though no one goes hungry.

This is because the Book of Mormon does not criticize the accumulation of individual wealth per se but rather the ostentation of great wealth. The “exceeding rich” are those the Book of Mormon ridicules for becoming “lifted up in their pride, such as the wearing of costly apparel, and all manner of fine pearls, and of the fine things of this world. And from that time,” it goes on to say, “they did have their goods and their substance no more in common among them” (p. 516). What the Book of Mormon counsels against, then, is conspicuous consumption. The Lord gladly showers his riches, material and spiritual. Those so blessed should be mindful, therefore, to avoid ostentation, parting with enough of their substance to look after the basic needs of the poor.

The Book of Mormon extolls the virtues of hard work and its concomitant rewards. Nephi instructs his people “that they should be industrious, and that they should labor with their hands” (p. 72). Wealth, if acquired in the proper way—by hard work, thrift, ingenuity, and a conservative but steady accumulation of surplus capital—is the fruit of righteousness. Jacob expounds the finer points of righteous acquisitiveness this way:

Many of you have begun to search for gold, and for silver, and all manner of precious ores, in the which this land, which is a land of promise unto you, and to your seed, doth abound most plentifully. And the hand of Providence hath smiled upon you most pleasingly, that you have obtained many riches; and because that some of you have obtained more abundantly than that of our brethren, ye are lifted up in the pride of your hearts, and wear stiff necks, and high heads, because of the costliness of your apparel, and persecute your brethren, because that ye suppose that ye are better than they. And now my brethren, do ye suppose that God justifieth you in this thing? Behold, I say unto you, Nay.

WHAT DISPLEASES the Deity is the gratuitous display of wealth, the tendency of some (not all) to deem themselves better than others simply because of their net worth. Jacob thus counsels the wealthier members of Nephite society to “think of your brethren, like unto yourselves, and be familiar with all, and free with your substance, that they may be rich like unto you.” Again, Jacob explains: “But before ye seek for riches, seek ye the Kingdom of God. And after that ye have obtained a hope in Christ, ye shall obtain riches, if ye seek them; and ye will seek them for the intent to do good; to clothe the naked, and to feed the hungry, and to liberate the captive, and administer relief to the sick, and the afflicted” (p. 126).

The Nephites under Alma also live briefly as a near-perfect society. “For the preacher,” Alma writes,

was no better than the hearer, neither was the teacher better than the learner: and thus they were all equal, and they did all labor, every man according to his strength; and they did impart of their substance every man according to that which he had, to the poor, and the needy, and the sick, and the afflicted; and they did not wear costly apparel, yet they were neat and comely…. And now because of the steadiness of the Church, they began to be exceeding rich; having abundance of all things whatsoever they stood in need; an abundance of flocks, and herds, and fatlings of every kind, and also abundance of grain, and of gold, and of silver, and of precious things; and abundance of silk and fine twined linen, and all manner of good homely cloth. And thus in their prosperous circumstances they did not send away any which was naked, or that was hungry, or that was athirst, or that was sick, or that had not been nourished; and they did not set their hearts upon riches; therefore they were liberal to all, both old and young, both bond and free, both male and female, whether out of the Church or in the Church, having no respect to persons as to those who stood in need; and thus they did prosper and become far more wealthy, than those who did not belong to their Church.

(pp. 223–224)

LATER ON, unfortunately, “the people of God began to wax proud, because of their exceeding riches … for they began to wear very costly apparel” (p. 230). And so, wealth became problematic.

By the time of Helaman, wealthier Nephites “obtain the sole management of the government, insomuch that they did trample under their feet, and smite, and rend, and turn their backs upon the poor, and the meek, and humble followers of God” (p. 425). White-collar, middle-class occupations suddenly appear, “for there were many merchants in the land, and also many lawyers, and many officers. And the people began to be distinguished by ranks, according to their riches, and their chances for learning … and thus there became a great inequality in all the land” (p. 466). Here is the economic pattern the Book of Mormon wishes to attack: the acquisition of wealth by unfair means, the denigration of labor, the ostentation of the rich and its debilitating effects on the lower classes, and finally the dire, long-term social and political consequences—anarchy, slavery, and, eventually, assimilation and/or genocide. A number of ideal Nephite societies come and go before the appearance of Jesus and this last-ditch attempt to reestablish an idealized agrarian social order based on conservative economic principles. It fails because of the emergence of a permanent aristocracy that amasses great wealth at the expense and dissolution of the social, economic, and political order.

The Book of Mormon, then, speaks to rich and poor alike. Yet the problem of poverty looms large, even during the best of times. In some respects, the poor, like the Lamanites, exist to test the mettle of the righteous. Ideally, the more affluent members of society exist to give a portion of their increase to the poor, not as a temporary respite but as part of a larger scheme to ameliorate economic hardship by encouraging the entrepreneurial spirit.

Poverty is a constant drain on Nephite high society, and the Book of Mormon takes a somewhat pragmatic approach. Even the unqualified words of King Benjamin, which adjure the righteous not to ignore the petition of the beggar (for we are all beggars at the judgment seat of Christ), has a caveat. King Benjamin’s philanthropy is decidedly right of center, for he also cautions: “See that all things are done in wisdom and order: for it is not requisite that a man should run faster than what he hath strength. And again, it is expedient that he should be diligent, that thereby he might win the prize” (p. 165). The prize is economic self-sufficiency and mobility. Feed a man for a day, but be sure to teach him to feed himself for a lifetime, too. The message here is quite conservative. Poverty is unavoidable but curable. Interminable poverty, on the other hand, is clearly a sign of poor character and altogether a different matter.

Finally, let us not confuse the passage in the Book of Mormon “I would that ye should impart of your substance to the poor, every man according to that which he hath … according to their wants” (p. 165) with the Marxian axiom “from each according to his ability to each according to his needs.” The Mormon version is more than likely Masonic in nature. Indeed, the Book of Mormon discussion of wealth and poverty and, in particular, of the centrality of charity is entirely consistent with the Masonic understanding. “Charity is the chief cornerstone of our temple,” Mackey writes in A Lexicon of Freemasonry, “and upon it is to be erected a superstructure of all the other virtues, which make the good man and the good Mason.”19 Christian Knights, not unlike King Benjamin in the Book of Mormon, are only in the service of God when serving their fellow beings. “Benevolence,” Grand Master Rob Morris writes in his “Practical Synopsis of Masonic Law and Usage,” “is one of the leading purposes of the Masonic Institution…. The rule is, ‘as much as the necessity of the applicant demands and the need of the giver justify.’” Here, then, is a more likely homology for the Book of Mormon’s ideas regarding the proper dispensing of charity to the poor.

Masonic charity militates against institutional assistance, what it calls “a regular fund set aside for that purpose.” Rather, “the hearts and purses of worthy Brethren” are said to “form an inexhaustible fountain for this purpose.” Moreover, the monitors stipulate that “any system of benevolence by which the dispensation of charity shall be equal in amount among the applicants, is unmasonic.”20 In the third section of the Entered Apprentice Degree “brotherly love” and “relief” are taught. “To relieve the distressed is a duty incumbent on all men,” the aspirant is told, “but particularly on Masons, who are linked together by an indissoluble chain of sincere affection. To soothe the unhappy, to sympathize with their misfortunes, to compassionate their miseries, and to restore peace to their troubled minds, is the grand aim we have in view. On this basis we form our friendships, and establish our connections.”21

In an increasingly mobile society, “needy strangers caught up in the … uncertainty of post-Revolutionary society,” Bullock writes, “found Masonry’s charitable activities a means of supplementing or even replacing the frayed bonds of family and neighborhood.”22 A widow might have little recourse but to exploit Masonry to great benefit since many local church assemblies were ill equipped or not inclined to be as generous. Masonry offered more than mere pecuniary compensation, digging deep into its pockets without so much as a second thought and providing the widow and orphan with a wide range of social services, too. That Masons were among America’s most acquisitive is not inconsistent with their philanthropy. A Masonic notion of having “all things in common,” as Bullock explains, “makes the prosperity of each individual the object of the whole, [and] the prosperity of the whole the object of each individual” (p. 197). This was the economic basis for the Mormon kingdom of God, perfectly consistent with the Nephite utopias in the Book of Mormon. The metamorphosis of the Law of Consecration and Stewardship into Tithing that transpired on the American frontier was not a departure, either.

Evangelicals attacked Masonic relief as mere influence peddling. And when Masons could no longer feed the throngs who appeared on fraternal doorsteps, Americans resented them for any good they had done or might still do. The Masonic economic vision of a voluntary welfare state (a network of old boys) had little choice but to see to the needs of native sons and daughters first. In practice, charity could not be wasted on the interminable poor. Masonic “honey,” as one fraternal humanitarian put it, had to be “well secured from the drones” (cited on p. 195).

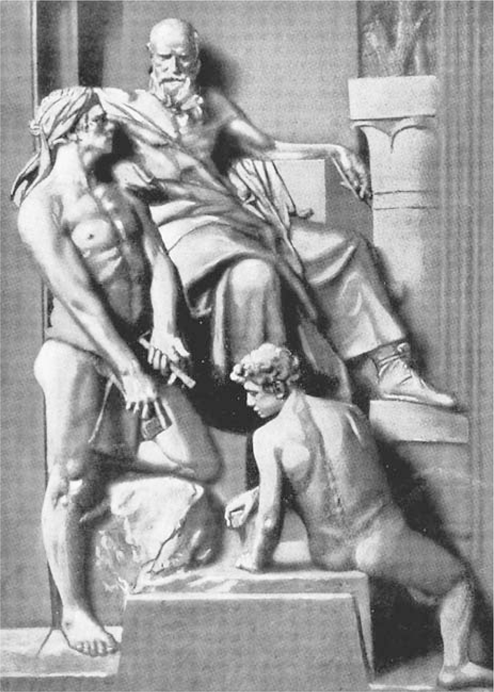

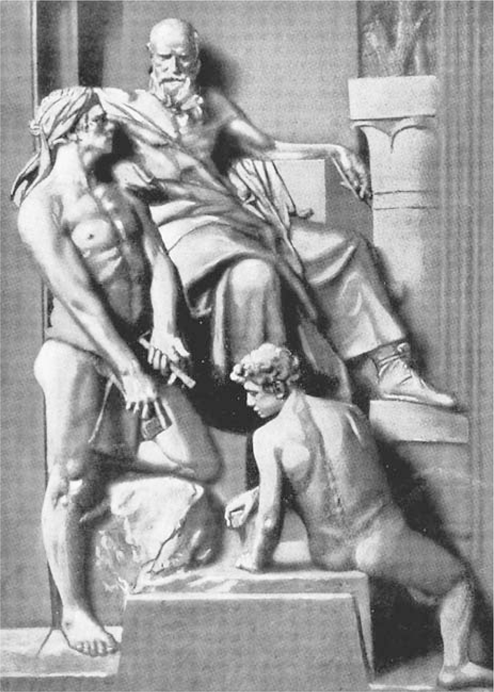

FIGURE 43 Labor Is Worship

Robert I. Clegg, Mackey’s Revised Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (Richmond, Va.: Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply, 1966), 1:588a.

The early Mormon economic kingdom of God operated according to the same principles and under the same strains, its economic resources far too meager to sustain a Masonic policy of poor relief that did not guarantee results. “And the idler shall not have place in the church,” one of Smith’s revelations says, “except he repent and mend his ways.”23 Interminable poverty might get one into the kingdom, but idleness could easily get one booted out.

The exclusion of certain ethnic groups (African Americans, in particular) by Masons and Mormons suggests that skin color, more or less as the Book of Mormon tells it, was seen as God’s way of screening applicants, allowing the church to hold on to the rich and the rich to the lion’s share by not forcing them to part with too much of their hard-earned profits to satisfy their obligation to the Lord and fellow human beings. The exclusion of Lamanites of all stripes (idlers one and all in the Book of Mormon’s proto—social Darwinist scheme of things) could be seen as good economic sense at bottom. Including women militated against a multicultural ritual, too, lest there be so little room for advancement that no one climbed the socioeconomic ladder and partook of the sweet fruit of the Acacia. It came down to a choice between race and gender in the end. The early Mormon attempt to liberate women was purchased at the expense of men and women of color, in particular. Moreover, it may not be a coincidence that since the lifting of the priesthood ban against Africans, the modern church has taken a harder and harder line against feminism.

The Evangelical alternative may not have been any more inclusive or free from racial bias. Feminism’s antebellum pioneers were racists of a different kind, confident that people not of their color could not compete in a free market. Let them try and fail. Let them watch, too, as white America took the lead through a process of natural (economic) selection. Masonry (and Mormonism, for that matter) had failed to understand that the emerging “herrenvolk democracy” was amenable to an ostensibly open-door racial policy.24 The Evangelical-feminist dream of ending discrimination based on race and gender was no less one sided, an equality of opportunity in which some were clearly more opportune than others.

The crusade for women’s rights, nearly two centuries in the making, transformed the “good men made better” of Masonic fame into self-made men, their male counterparts lower down the ladder of success becoming the caricatures of humanhood featured in Susan Faludi’s recent book Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, searching for substitutes for the fraternal burst of light, rattling sabers, and institutionalized philanthropy of bygone days.25 Boys will be boys. The founder of Mormonism seemed to understand the American male and his need for masculine role models, the future Church of the United States likely some veiled Masonic reaffirmation of the rights of men to moral self-determination, to worship God, and raise their kids according the dictates of their own consciences.