INTRODUCTION: THE WAX AND WANE OF MASONRY IN AMERICAN CULTURE

Masonry, like Christianity, must have her indiscreet champions.

History of the Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons

WHO ARE THE MASONS? In some respects, the question is not so much who they are but who they were. How many Masons are there worldwide? Depending on whom one asks, anywhere from one to five million. In the United States and Canada, for example, most towns and villages—and certainly larger metropolitan centers—have a Masonic temple to their credit, such inauspicious insignia as carpenter square, engineering compass, and capital G (a testament to Masonic reverence for the Deity) perhaps the only clues to what goes on (or perhaps went on) behind closed doors and boarded windows. And although some of these are merely architectural monuments to a bygone era, relegated to the status of local tourist attraction and cultural artifact, many are still in operation. At present, Masonry is growing by leaps and bounds in Latin America.1 (Incidentally, Mormonism has also done well in Latin America.)

Whether Masonry simply refuses to die or is alive and well, there is no question that rumors of its death are greatly exaggerated. The apparent numerical strength of the movement of late has been long in coming and hard sledding, a remarkable comeback in the wake of some crushing defeats—one, in particular. No one knows better than Masons that a single blow on the chin can cost as much as the heavyweight championship of the world. And although the order will never live down the murder of Captain William Morgan by New York Masons in the mid-1820s, for which it was found guilty in the court of (Evangelical) public opinion and sentenced to obscurity at the time, it has nonetheless paid its debt to society and been granted an early parole (perhaps for good behavior).

The question of who the Masons are should perhaps begin with when they first were—in other words, whether they can truly claim to be an ancient order of men and women, and, if not, what this might say about them. Masonry traces its origins to ancient Palestine and the construction of the temple of Solomon, claiming Hiram Abiff, Solomon’s chief architect, for its own. Murdered at the hands of fellow craftsmen for refusing to divulge craft secrets before the temple could be completed, the story of the death and resurrection of Hiram Abiff is to Masonry what the Exodus is to Judaism and, indeed, the crucifixion of Jesus Christ is to Christianity. It turns out that the gruesome killing of the first Master Mason was not to keep trade secrets from leaking out (nor to protect some formula for the perfect mortar or a more economical solution to an engineering or architectural conundrum that competitors would surely steal) but rather about how to prevent religious secrets (male mysteries) from falling into the wrong hands. Hiram Abiff is held up by Masons the world over as a symbol of virtue and bravery (in the manly arts), and Masonic ritual at its core is a memorial to this everyman’s man’s man.

Profane history is conspicuously silent on the matter. There is no mention of Hiram Abiff per se and a scuffle involving a chief architect and an impatient pack of vengeful apprentice masons in the Bible. Nothing about a search party of loyal followers apprehending the murderers (tearing out their tongues, slitting their throats, and spilling their guts as punishment) and finding the body of their mentor so badly decomposed that they had to lift it from its shallow grave using an intimate male embrace known in Masonic rituals as the five points of fellowship. Nor is it anywhere said that afterward Solomon, king of Israel, revealed to this faithful few a grand omnific word, instructing them in the niceties of a ritual in honor of their fallen general.

Extracanonical sources (the Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, Dead Sea Scrolls) prove no help, either. In fact, the paucity of documentary and archaeological evidence suggests that the story of Hiram Abiff is simply a figment of some fertile imagination. But, then again, so were Moses and possibly even Muhammad. Gautama the Buddha is more than likely an invention. The list is endless. And while the founder of Christianity is uniquely historical, there is the unfortunate and inescapable fact that the New Testament offers the only proof of his resurrection. Of course, there is still plenty of optimism in both the Christian and Masonic camps that someday a pristine document will appear on the scene—locked away in some subterranean vault—testifying to the truth of the resurrection of Jesus Christ and the exhumation of Hiram Abiff, respectively.

The search for such a text is the mythica stock-in-trade of Masonry—and of Mormonism, too. In both cases, the hoped-for proof takes the form of the golden plates (of Enoch), one or several, and/or a lost gospel that is said to have made the rounds, discovered and rediscovered by Masons and would-be Masons. First a bit of serendipitous excavating at the construction of the Second Temple and then digging through the rubble in the aftermath of its destruction by the Romans set the stage for a kind of quest for the holy grail: the discovery of the father of all patriarchal scriptures, Enoch’s lost engravings, to which Jesus will be privy in time. The Lord and Savior, it turns out, was a member of the brotherhood. The list of distinguished Old Testament and New Testament Masons grew as the movement pushed forward into the Middle Ages, adopting the heroic French Knights of Templar in the corps of manly men, although they were but honorary members at first. Betrayed by King Philip IV of France and Pope Clement V at the beginning of the fourteenth century, according to some Masons, the Templars were not all murdered,2 a faithful remnant sailing to America long before Columbus, navigating using a “lodestone compass and astrological maps” (p. 77).3 They also carried with them a secret gospel of Jesus—a pristine copy of the scriptures, in short—that they hid lest it fall into the hands of mendacious and willful copyists.4

This, of course, is the bare-bones Masonic account. Depending on who you read, the order traces its origins to Adam in the Garden of Eden, or to the Tower of Babel, or only to the construction of the Temple of Solomon, perhaps as recently as the Second Temple and the advent of Jesus, or—playing it really safe—the Crusades. It can all get terribly confusing. How Jesus got on the ticket, for example, is a good question—he was a good vice president but only picked to mollify the Christian element in the party, meant to be seen (at fund-raisers mostly) but not heard. What role the Knights Templar played in the new administration and its bloated bureaucracy of new arrivals is no less problematic. The War Department? The Justice Department? Secretary of Defense? Secretary of State? Then again, in the opinion of some, the Knights Templar are no less ceremonial than Jesus (their mentor), representing the pomp of Masonry and no more than that. Their critics within the movement are inclined to characterize them in the most unfavorable light as a bunch of saber rattlers who only knew how to toot their (own) horns in military formation as loudly and as inharmoniously as possible, to the cheers of an undiscerning crowd. The idea that such men and women (among their apparent failings is a fledgling belief in women’s rights), the idea that women could ever be accorded any real power (or the priesthood) stretched the limits of Masonic credulity.

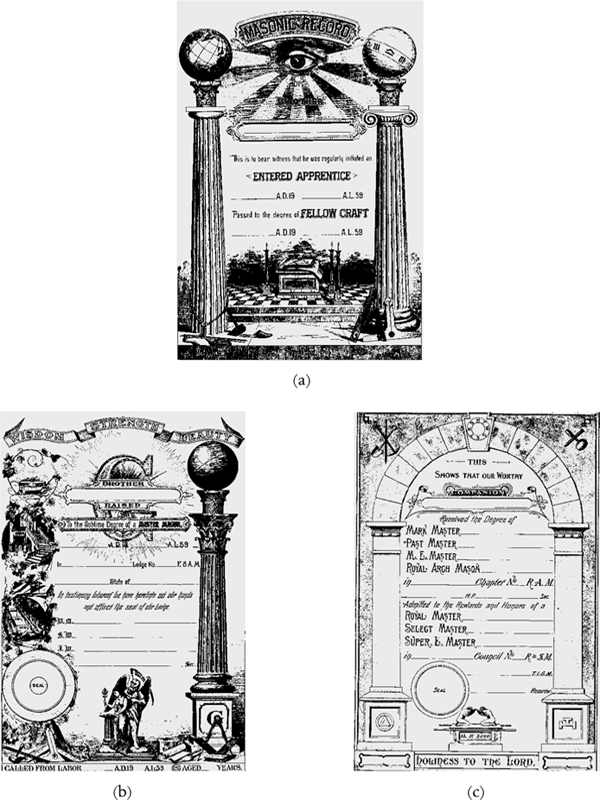

FIGURE 3 a. Masonic Degree Certificate b. Master Mason Degree Certificate c. Royal Arch Degree Certificate

Preface to Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John C. Yorston, 1911), vol. 1.

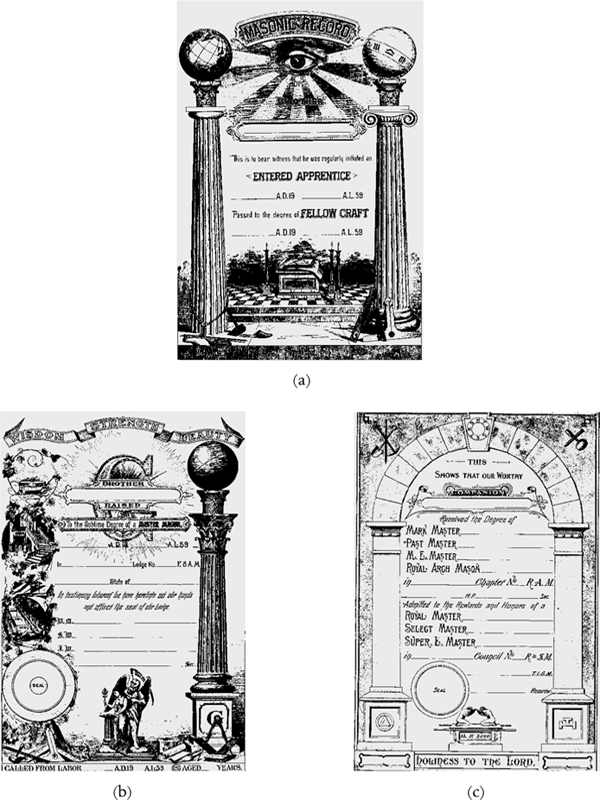

FIGURE 3 d. Scottish Rite Degree Certificate e. Miscellaneous Higher Degrees f. Knights Templar Degree Certificate

Preface to Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John C. Yorston, 1911), vol. 1.

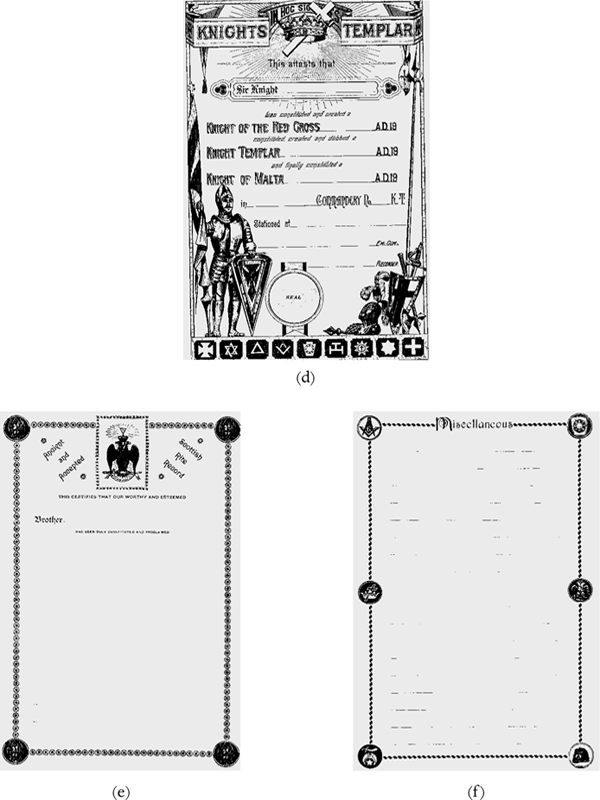

A dispute over the role of Jesus and his crusading knights has raged for centuries, but only two or three rather than ten or twenty. The oldest Masonic Grand Lodge on record dates back only to 1717, located in London, England, not Jerusalem. It consisted of two and then three degrees: Apprentice, Fellow Craft, and Master Mason. The lodge practiced the oldest and most orthodox variety of Freemasonry, known as Craft Masonry (Tory blue was its color of choice, hence the appellation Blue Lodge). The Masonic Knights Templar come later, a mid-to late-eighteenth-century invention of British/Scottish design, the brainchild of Andrew Michael Ramsay, a nobleman with a flair for the dramatic. Chevalier Ramsay, the French title notwithstanding, was a Scot and a bit of a rabble-rouser. The new system of degrees he inspired and all the attendant medieval mythology (chiefly regarding the Knights Templar) made the order more accessible to moderate propertied men despite the fact that his intention was to make it more aristocratic. Craft Masonry had become a crafty business, indeed, made up exclusively of the aristocracy (English, French, German, and Russian). The advent of Royal Arch masonry changed this, adding to and expanding on the original three. Its spin on the discovery of lost scripture in the Bible turned the tables, accusing Craft Masonry of being a modern invention. Ironically, devotees of the older Craft degrees would be forced to accept the polemical designation he assigned them, “Moderns,” despite the fact that the real moderns were Ramsay’s self-proclaimed Ancients. Proponents of this Royal Arch or Ancient Masonry, not too surprisingly, dress themselves in red.

High atop the Royal Arch were the so-called Chivalrous degrees, where the Masonic Knights Templar and other Christian degrees were entered into the books—white and black the colors of the Knights Templar. There are other degrees, in the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, for example, a fork in the ritual road. After becoming a Master Mason, one has the choice of pursuing the Royal Arch and/or the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. The Royal Arch gets one to the top of the mountain quicker, consisting of only thirteen degrees all told, whereas the Scottish Rite has more than double that—twenty-nine in all, not counting the initial three of Entered Apprentice, Fellow Craft, and Master Mason. At the summit, a degree entitled “Sovereign Grand Inspector General” makes the total thirty-three. In fact, however, should one choose to make the climb to the summit via both the Royal Arch and the Scottish Rite, this is entirely acceptable, for the argument is that nothing truly exceeds the Third Degree of Master Mason.

There is considerable overlapping and even a measure of professional jealousy between Royal Arch and Scottish Rite Masons.5 To avoid confusion, I will take Webb’s Monitor, which adheres to the York line of progression, as normative. It consists of the following: the Capitular Degrees of Mark Master Mason, Past Master, Most Excellent Master and Royal Arch Mason, followed by the Cryptic Degrees of Royal Master, Select Master, and Super Excellent Master, these last make one eligible to apply for membership in a “Commandery” or “Encampment” of Knights Templar and receive the degrees of Red Cross Knight, Knight Templar, and Knight of Malta.

Masonry (red, white/black, and blue) made the perilous journey across the Atlantic in plenty of time to play a role in the War of Independence and the governance of the Great Republic in the years to follow. Whether Masons were patriots or not seems to have depended largely on what kind of Masons they were. Royal Arch or York Masons (their penchant for red notwithstanding) wore a blue uniform as a rule, whereas blue-blooded Craft Masons tended to drape themselves in red. After a bloody civil war with Mother England to rid the colony of the vestiges of monarchy, one might wonder why the idea of draping the entire country in the black robes of French monasticism and medieval chivalry was never more appealing. But if this seems quite unthinkable at the dawn of the first republican democracies in the modern age, we postmoderns should consider that our own history has a few (Masonic?) wrinkles that may need ironing out—the War of Independence may have been fought to revitalize the eighteenth-century republican-monarchical synthesis being one.6 Whatever the reasons, the Masonic presence in American society was significant immediately following the Revolution and up until the murder of Captain William Morgan in the late 1820s. For as many as fifty years, if what Brooke and others have to say is correct, Masonry played a profound role in the new republic at every level of government.7

From small acorns grew a mighty oak of liberty (watered with blood of patriots who liked to play dress-up?). In some important respects, Masonry (not unlike America) owes its existence to the tradition of boys’ night out, the need for exclusive male companionship felt most acutely in the eighteenth century by many in the upper classes, who wished to flee the debilitating effects of parlor and pulpit for the freedom of wrestling their chums to the ground under cover of darkness, dancing half naked, beating their chests, and howling at the moon with impunity. At worst, Masonry was and is the stuff of Peter Pan. From the start, though, such male bonding was attacked as Satanic. That this accusation was quite false, together with the one that Masons drank blood,8 made no difference: the clergy (Catholic and Protestant) still saw red. It is difficult to say what bothered America’s Evangelical establishment more: that Masonry seemed poised to replace them as the core religion of the United States or that it threatened to become the official church of the nation. And the fact that Masons had Jesus on the ticket only made matters worse. Tony Fels explains that Masonry became the basis for a widespread “non-Evangelical alliance.”9 In short, orthodox Protestants had been right to suspect that Masonry (and Christian Masonry especially, should it ever get up and running) did not bode well for the future of Evangelical Protestantism in America. Masonry in Federalist Connecticut, as Dorothy Ann Lipson explains, “commanded … wide participation and allegiance and became the prototype of most other fraternal and service organizations.”10 Elsewhere she goes on to say that the “single most threatening aspect of Masonry was that some members used the association as if it were a religious denomination or, more threatening yet, an alternative to religion” (p. 8).

Colonial Masonry posed less of an immediate threat; it was the domain of too many gentlemen. As Steven Bullock explains, the lodge was largely a place to “build elite solidarity and to emphasize their elevation above common people.”11 Nothing about the degrees, offices, or even the lodge itself was likely to attract adherents from the middling ranks. Evangelicalism was quite safe.

Colonial Masons were notorious for their elegant attire, the Masonic funeral procession an ostentatious affair, underscoring an apparent lack of political, social, and economic decorum in the face of democratic reforms. Their gaudy dress made an even bigger splash at theaters and local clubs, and they upstaged the clergy at swanky religious affairs whenever they could (p. 57). Not the stuff of the local corn boil, Masonic banquets were notorious for being overly posh affairs—second only to the lodge itself, which was pricier and more exclusive by far. Moreover, “the deliberately high expense of Freemasonry,” Bullock writes, “formed only one of a series of barriers meant to keep out the improper” (p. 63). The secret ballot and black ball guaranteed the exclusion of any coarse and blundering common folk (p. 68).

However, as the mood of the country changed from exclusion to inclusion, so did Masonry. In fact, it placed supreme faith in a kind of moral trickle-down effect. George Washington’s famous dedication of the Capitol in 1793 as a Masonic temple is a case in point. This was no mere cornerstone ceremony using the Masonic symbols of corn, oil, and wine—though it was (and still is) customary for Masons to dedicate most buildings (even churches). Dusting off his Masonic cap and gown, Washington used the event to redefine America’s place in history according to a Masonic timetable, “the year of Masonry, 5793” (cited on p. 137). The importance of the event was not lost on Thomas Jefferson, who took for granted that the Capitol was a monument to the greater Masonic good of the new republic—a “temple [Masonic lodge] dedicated to the sovereignty of the people” (ibid.). The idea of the White House as Grand Lodge (an idea only, but a grand one all the same) had important implications for the thousands of lodges to spring up in the coming years, consecrated to the American way and where the business of American republicanism and moral education of the citizenry would take place from the ground up. Rather than a conflation of lodge and state, though, Masonry and Washington, D.C., were a symbiosis—a close association of two dissimilar organisms that was mutually beneficial.

FIGURE 4 The Goose and Gridiron Tavern, London, birthplace of the Grand Lodge of England

Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John C. Yorsten, 1911), 3:134a.

FIGURE 5 Brother George Washington, Master Mason, August 4, 1758

Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John C. Yorsten, 1911), 4:362b.

In fact, Masonic dedication of the Capitol can also be seen as an attempt to co-opt the order. Washington was a practicing Mason, but, when pushed, he was just as likely to reprimand the brotherhood in the interest of political expediency. Neither could Jefferson be trusted to defend Masonry, right or wrong, for he was an outsider through and through. Even Benjamin Franklin, perhaps the most dogmatic of the Masonic founding fathers, put his fraternalism in a bottom drawer, and, not unlike the piety of Oliver Wendell Holmes, when he opened that drawer years later he discovered to his dismay that it was empty. Franklin, like many Masons of his class at the end of the eighteenth century (and indeed as they reached ripe old age themselves), seemed to abandon an order that, for him at least, had outlived its usefulness. Franklin’s rise up the ranks may be attributable to his erstwhile Masonic vows and associations, but he may have turned away from them when he found something infinitely more gratifying than its ritual celebration of science and learning. Masonry itself changed to suit the times, favoring more mainstream messages and methods. The new message was that a naive belief in science and a plethora of newfangled gadgetry would make of a nation of republican behavers, Masonic believers, and vice versa.

Enter the great bugaboo of postmodernist angst: mass media. In light of the democratization of information, Masonry’s days were perhaps numbered, the idea of passing knowledge from father to son bound for the scrap heap. The free press, not the freemason,13 would become the medium of the new age for the “instruction of all ranks of people … in those secrets of the arts and sciences” hitherto the preserve of so many gentlemen.14 Ironically, the apotheosis of science quickly turned the lodge into the abode of just as many gentlemen as before, snooty afficionados of the cult of pure reason. Potential lovers of learning, taste, and philosophy who required a leg up were getting the boot in order to make room for the likes of Tennessee Grand Master Wilkins Tannehill. His 1829 Sketches of the History of Literature, a sophisticated translation and exegesis of ancient Palestinian texts, speaks volumes of a creeping elitism. Tannehill’s characterization of the work as but “the humble pretensions of a backwoodsman” has all the credibility of a political acceptance speech in the antebellum Deep South.15 The concessions necessary to keep Tannehill happy were almost certain to anger so-called lesser men, the generation of young American males on the frontier eager to stake their claim in accordance with a more democratic order of conduct.

“By the beginning of the … century,” Bullock writes, “more American lodges met in inland villages than on the urban seaboard.”16 Masonry in America divided squarely down the middle between Ancients and Moderns. Brooke argues in the same vein:

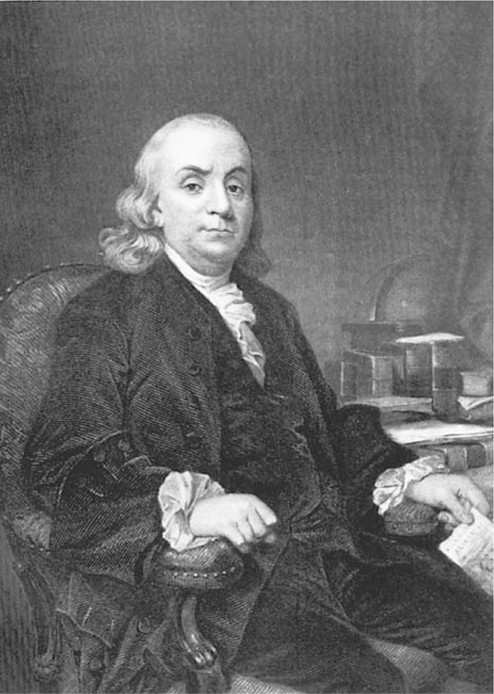

FIGURE 6 Brother Benjamin Franklin, Provincial Grand Master of Pennsylvania, 1734

Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John C. Yorsten, 1911), 4:244b.

Royal Arch Masonry, after all, had been born of schism and class strife … a group of provincial lodges declared themselves the “Ancient Rite” and decried the London Grand Lodge as a debased “Modern” version. In great part this was a class-based schism, with artisans and small shopkeepers resenting the pretensions of the aristocrats who controlled the London Grand Lodge. The Ancient Masons claimed that the London Grand Lodge had changed Masonic history in abandoning some of the material connecting the order to Old Testament times. But the Ancients made innovations of their own, adding a fourth degree, the Royal Arch, to the three basic degrees of Entered Apprentice, Fellow Craft, and Master Mason.17

THIS IS NOT TO MENTION the story of Enoch’s underground vault of lost wisdom inscribed on gold, brass, and marble that he hid there for safekeeping and future reference should the standing order get too big for its britches.

As early as Franklin’s return to Philadelphia in 1785, the Royal Arch, or Ancient Order of the Priesthood, was a force to be reckoned with. Suddenly, it was the cosmopolitan Franklin who was not likely to feel much like participating; nor was he entirely welcome to do so, not without submitting to a somewhat degrading healing ceremony. His refusal, claiming it would be unbecoming to a gentleman, could only be interpreted as a thinly veiled criticism of the entire nascent Royal Arch or York system of Masonry. When Franklin died five years later, Philadelphia Masons (almost to a man) failed to attend his funeral, let alone give the event their blessing. If blackballed in death by these “pretenders to the throne,” this slight however one conceives it would not have caused him to shift his weight to one side, let alone turn in his coffin. Whether Moderns or cosmopolitan Masons like Franklin were guilty of climbing into bed with the state and thus deserved what they got was most assuredly a moot point in the years to follow. The Ancients quickly made it their mission to court the church with the same gusto.

Enter the Knights Templar, an honorary set of Masonic degrees on the books for a little while at this point. These new kids on the (Masonic) block were patterned after the New Testament rather than the Old (a significant departure), representing a small but significant patch of common ground where a historic Masonic-Protestant interfaith dialogue might take place. The case of New York Royal Arch Mason Salem Town is instructive. His System of Speculative Masonry (1818) argues that Masonry and Christianity are “the same truth” and thus both divinely inspired.18 While the marriage was not quite made in heaven, the fraternity’s standing in the eyes of the public made some enormous gains as it attracted growing numbers of the clergy in its ranks.19 Town was one of several Christianizers of Masonry, hoping to mend the rift that divided Ancients and Moderns by means of a Christian exegesis of the Craft degrees, in particular seeing in the raising of the Master Mason a type of Christ. George Oliver, an English cleric of noble Anglican blood, was another.20 His Christian spin called for a much older dating system for the order—reaching back to the time of Adam and Eve, no less—claiming that Seth had practiced a form of “Primitive or Pure Freemasonry” that, among other things, had been a rite that anxiously awaited the coming of Christ.21 The third member of this trinity was another Englishman, William Hutchinson, whose Spirit of Freemasonry (first published in 1775) would be translated into several languages and undergo numerous printings but, owing to its exclusively Christian interpretation of the Master Mason degree, as one Masonic encyclopedia explains, would “not be received as the dogma of the present day.”22 The ecumenism of Oliver and Hutchinson bore fruit nonetheless, the so-called Union of 1813 that, in England at least, brought an end to the bitter rivalries that had divided Ancients and Moderns, who came together under the present United Grand Lodge of England, which nevertheless seems to favor the Moderns (2:1066).

Ancients and Moderns battled it out on American soil, too, with the Ancients winning the battle but not the war. The war would be a very different fight, indeed, rather less amenable to union as such—and between the Royal Arch Knights Templar and the Scottish Rite. The latter, a plethora of knightly designations with a gnostic and hermetic quality, came to the United States by way of Charleston, South Carolina, in 1783, its first Supreme Council headed by John Mitchell and Frederick Dalcho in 1801 (2:916). The Scottish Rite is the more esoteric of the two, having a neo-Christian agenda, boasting thirty-three degrees in all:

I. SYMBOLIC LODGE

1. Entered Apprentice

2. Fellow Craft

3. Master Mason

II. LODGE OF PERFECTION

4. Secret Master

5. Perfect Master

6. Intimate Secretary

7. Provost and Judge

8. Intendant of the Building

9. Elu, or Elected Knight, of the Nine

10. Illustrious Elect, or Elu, of the Fifteen

11. Sublime Knight Elect, or Elu, of the Twelve

12. Grand Master Architect

13. Knight of the Ninth Arch, or Royal Arch of Solomon

14. Grand Elect, Perfect and Sublime Mason, or Perfect Elu.

III. CHAPTER OF ROSE CROIX

15. Knight of the East

16. Prince of Jerusalem

17. Knight of the East and West

18. Prince Rose Croix

IV. COUNCIL OF KADOSH

19. Grand Pontiff

20. Grand Master of Symbolic Lodges

21. Noachite, or Prussian Knight

22. Knight of the Royal Ax, or Prince of Libanus

23. Chief of the Tabernacle

24. Prince of the Tabernacle

25. Knight of the Brazen Serpent

26. Prince of Mercy

27. Knight of the Commander of the Temple

28. Knight of the Sun, or Prince Adept

29. Grand Scottish Knight of Saint Andrew

30. Knight Kadosh

V. CONSISTORY OR SUBLIME PRINCES OR MASTERS, OF THE ROYAL SECRET

31. Inspector Inquisitor Commander

32. Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret

VI. SUPREME COUNCIL

33. Sovereign Grand Inspector General—Honorary

With so much about the order (both the Royal Arch/Templar and Royal Secret/Scottish chivalric streams) that was friendly to Christianity (and despite its medieval and even Roman Catholic airs) the Protestant clergy in America were inclined to lend their support—so long as they received special treatment, that is. Masons were quick to oblige, too, remitting membership fees for the clergy as a matter of course.23 A new office was created in the Royal Arch or American Rite, that of “Grand Chaplain.” The Grand Lodge of Connecticut appointed W. Bishop Jarvis of the Episcopal Church to preside over its meetings, public and private (pp. 128–129). Over a hundred clergy had joined Connecticut lodges by 1830, a third of them Episcopalians (p. 128 n. 35).24 The other two-thirds were Universalists, including Hosea Ballou and Elnathan Winchester, cofounders of Universalism in America.25 At first, as Lipson explains, “the only available [clerical] sponsorship came from countervailing denominations.”26 Before long, however, Congregationalists in Connecticut had buried the hatchet. In 1825 the Grand Lodge appointed its first Congregational Grand Chaplain, the Reverend Charles A. Boardman of New Preston (p. 131). Methodism followed suit, the eccentric itinerant minister Lorenzo Dow preaching the message of Christian Masonry throughout the land and with impunity.27 The editor of the Methodist Zion’s Herald likewise saw no contradiction between his Christian faith and Masonic vows.28 Masons began holding some meetings at local Evangelical meeting houses, another testament to Masonic-Protestant relations. At about this time, religious tests were added to the Masonic ritual in order to reflect better the new, middle-class Evangelical sensibility: belief in God, in the divinity of Jesus Christ, and in his resurrection, as well as the exhumation of Hiram Abiff.

For some, the growing Evangelical presence at the lodge did not bode well for the order. A degree of sectarian divisiveness was detectable, too, something foreign to Masonry, in principle at least. The so-called Jewish question divided Royal Arch Masons along promission and antimission lines. In 1822 the Hiram Lodge of New Haven formed the New-Haven Palestinian Missionary Society in hopes of diffusing “the Holy Scriptures among benighted heathen people, and having a particular desire to promote the happiness of our Jewish brethren, and others in Palestine.”29 In 1823 the Olive Branch Council of Select Masters—a Royal Arch lodge—sent the following admonition to the brethren in northeastern Connecticut, stating that in

the general spirit of philanthropy to awake from [their] slumbers to demonstrate, by active benevolence, that when we speak of Masonry, we mean something more than the gratification of the Epicure—Where are the descendants of those Master Builders, who rendered Mount Moriah the religious center of the world? To the Jewish Nation we are indebted for all that is ancient, judicious and distinct in Masonry. From them under the great I AM, we derive all we know of the history of man and the will of Heaven, anterior to the advent of the long promised Messiah.

(cited on p. 183)

IN THIS WAR OF WORDS, Masonry seemed to take on the appearance of its nemesis, Evangelical Protestantism.

In 1816 the General Grand Encampment of the United States was formed, with DeWitt Clinton (New York’s governor, no less) named General Grand Master and Thomas Smith Webb Deputy General Grand Master. Templars were to be found in New York before this, but as “Sir Knight Robert Macoy,” Grand Recorder of the Grand Encampment of New York in 1851, would later go on to lament, the Knights Templar of that state did not receive authorization to grant warrants until 1797.30 One reason for confusion is that New York state had been home to numerous self-created Templar Encampments “governed by their own private and individual laws, acknowledging no superior authority” (5:218). DeWitt Clinton may have hoped to effect a union of his own, rallying New York’s best and brightest, elites of Masonic-Christian sensibility, to help to reestablish the old pecking order in the interest of social harmony—and likely to increase Masonic coffers and his chances for reelection, too. In the Conventions of New York Knights Templar for the years 1816, 1819, 1826, and 1829 the names of the state’s upper crust appear in spades. Notably, the presiding General Grand Prelate at the time of the Morgan affair was the distinguished Rev. Paul Dean (1816–1826); thereafter the title passed to Rev. Gregory T. Bedell (1826–1829) and then to Rev. Ezekiel L. Bascom in 1829. The Grand Encampment of the United States was not so much grand as an elitist and priestly bunch as deeply divided as any Protestant assembly of the time. Then, to make matters infinitely worse, under the not so watchful or moral eye of the same Grand Encampment of Knights Templar, there followed a murder indictment and attempted cover-up. Was the game over? The end of Masonry or just the beginning?

Enter Joseph Smith Jr., the soon-to-be Mormon prophet. Had the founder of Mormonism been able to waltz into one of several lodges in the immediate vicinity—at twenty-one, as was the custom and his birthright, being of Royal Arch stock—had he been able to start the long ascent up the mystical ladder of manhood through the normal channels (all things being equal), he no doubt would not have gone on to become the Mormon prophet but a Masonic luminary of some lesser distinction. The Morgan affair, in short, left young prospective Masons of Smith’s generation without a lodge to be in. In Smith’s case, he ran the risk of being rejected on account of a limp, and so, in some respects, massive lodge closures gave him just the excuse he needed to start something Masonic of his own.

Morgan’s widow later became one of Smith’s wives, but he and Morgan had more in common than a liking for the erstwhile Lucinda Pendleton.31 But that they shared a strong desire to bring Masonry down a notch or two is no foregone conclusion. First Morgan and then Smith might just as easily be seen as among Masonry’s so-called indiscreet champions. Supporting this is the very plausible Masonic retort that Morgan’s death was a freak, an accident, the work of rogue Masons who at worst were guilty of negligent homicide, not a cold or calculated act of premeditated murder, and that the Grand Lodge had no hand in it. What, after all, had Morgan done that was so wrong? Was it really that he hoped to bring down the order by publishing a blow-by-blow account of the ritual? Or was it that by doing so he threatened to rally Masons or would-be Masons around a new captain of the guard—men of his social standing who, like him, were being discriminated against on the basis of their class?

Morgan’s Masonic credentials are spurious at best. Allegedly, he was a Royal Arch Mason and member of the LeRoy, New York, Lodge (No. 33) in 1825, declaring on his honor to have received the previous six degrees in the “proper manner.”32 Moving to Batavia a short time later, he was denied admission to a Royal Arch chapter there. A petition for a new one bearing his name was also rejected, whreas a second containing the names of Batavia’s better sort (who were openly hostile to Morgan) proved successful. And if that were not enough, when Morgan swallowed his pride and tendered an application to join, he was blackballed. This marked the end of his Masonic career for all intents and purposes. Teaming up with another blackballed applicant, editor of the Republican Advocate David C. Miller, he no doubt hoped to get even, living the good Masonic life—with or without the blessing of the Grand Lodge—as the best revenge. That he intended to publish a Masonic manual or “monitor” rather than a mere Evangelical polemic in the hopes that large numbers of like-minded men would follow his lead is not an impossibility.

It makes no sense to say that Morgan stepped over the line and out of the Masonic camp when he published his Illustrations of Freemasonry, given the vast number of Masonic monitors in existence, available to the general public and containing long excerpts from the Masonic ritual—some of these as detached as Morgan’s. The gentlemen of the Jerusalem Lodge in London, for example, published an account of the Masonic rituals as early as 1762, the famous Jachin and Boaz, defending their publication as a pro-Masonic work designed to “strengthen [rather] than hurt the society … to please … [their] brethren” and most certainly not done with ‘a view of gain.’”33 In their view, a candid account by Masons of the rituals to manhood could prove beneficial to the movement, preferable to that “which hitherto has been represented in such frightful shapes” by their enemies (p. iv). Morgan’s Illustrations of Freemasonry contains little in the way of editorial comment, presenting rather an unvarnished recitative that took its cue from William Preston’s Illustrations of Freemasonry (first published in London in 1772)34 and Thomas Smith Webb’s famous Freemason’s Monitor; or Illustrations of Freemasonry (first published in the United States in Albany, N.Y., in 1797). Thirteen editions of Jachin and Boaz had been published in America between 1790 and 1820. It seems that Morgan had every Masonic right to add to the corpus.

By the time Morgan’s turn came along, however, it was becoming fashionable to nip such revisionism in the bud. American Royal Arch Masons were closing ranks around Webb’s Monitor, elevating it to canonical status. Webb was well positioned, a Masonic leader at the state level. Postbellum Masonic apologist Rob Morris explains in the preface of his edition of the Monitor: “In all my teachings as a Masonic lecturer, I have urged that whatever merits the fifteen or twenty Handbooks in use among us possessed over this, or one another, it was merely for their pictorial embellishments; the monitorial and really essential parts being but copies of this, with unimportant additions. I have never thought their dissemination, to the exclusion of Webb’s Monitor, the true policy of the Craft.”35 Morris continues: “If, as is fondly hoped, the establishment of Masonic Schools of Instruction, teaching nothing but the ‘Webb Work,’ should be crowned with general success, an important feature in them must be a uniform text-book. The FREEMASON’S MONITOR must of course possess the only claim to that position” (p. x). One detects a Protestant canonical bias here, a variant of the sola scriptura doctrine, with Webb and only Webb as the standard for belief and practice. Publishing a competing Masonic monitor in America after 1819 (superseding Webb in some way) had become a risky business by the late 1820s. Morgan perhaps knew this but was willing to risk it. He paid with his life.

More problematic by far than Morgan’s murder, it turns out, was the Masonic establishment’s attempt to cover it up. Men of standing and honor, indeed! Let New York Masonry say what it will about a bribe that Morgan allegedly took to disappear forever, there is no way around the issue of Masonic jury tampering. Hiram Hopkins, implicated in the kidnapping, recalled that during his own Masonic initiation ritual in August 1826 his “guide” had first informed him of Morgan’s plans to “publish Masonry.” He also confessed that he thought Morgan “deserved to die.”36 Such stern enforcement of the penal oath of absolute secrecy is rare, but rumors of Morgan’s plan to reveal the “Grand Omnific Royal Arch Word” sealed his fate.37 Masons put pressure on Morgan and Miller not to publish Illusrations of Freemasonry, going so far as an attempt to burn down Miller’s printing office. What came out did not go beyond the first three degrees, in fact. Morgan may even have survived its publication—but not for long.

FIGURE 7 Brother Thomas Smith Webb

Robert Freke Gould, A Library of Freemasonry (London: John C. Yorsten, 1911), 5:478b.

The following detailed description in Samuel Prichard’s Masonry Dissected of the penalty for breaking one’s promise “not to Write” the secrets or “cause them to be written” paints a gruesome picture and may explain why Morgan’s body was never recovered. The oath of secrecy in Prichard’s monitor is a ban on publication “under no less penalty,” it says, “than to have my Throat cut, my Tongue taken from the roof of my Mouth, my heart plucked from under my left breast; then to be buried in the Sand of the Sea, where the Tide ebbs and flows twice in twenty-four Hours; my body to be burnt to Ashes, my Ashes to be scattered upon the face of the Earth, so that there shall be no more rememberance of me among Masons.”38 Suffice it to say that the murder, if Masonic, did not have the desired result.

Hopkins, who turned state’s evidence and then on his brothers, would eventually claim that he had been shocked to learn that his cousin, Niagara County sheriff and coconspirator Eli Bruce, executed Morgan a few months later merely to avoid prosecution. It was a despicable, stupid killing utterly unbecoming of the brotherhood—secret blood oaths notwithstanding. That was not the biggest problem, however. At the behest of Bruce, Hopkins allegedly packed the jury with fellow Masons, who swore an oath to perjure themselves. When it was all over, a few convictions were handed down, but sentences seemed on the short side. Bruce, who orchestrated the kidnapping and brutal slaying, only got a little over two years.39 Regardless, Masonry would pay dearly in the months to come, not for the murder so much as for its role in the cover-up. But if the Morgan affair brought about the end of an administration, it was not the end of Masonry—far from it. American Masonry would live to fight another day, and not simply because of the efforts of its Robert Morrises but because of its William Morgans, too.

Thomas Paine’s incendiary Age of Reason (part 1 published in 1794, part 2 in 1796) is a case in point—a thinly veiled defense of Masonry that attacked revealed religion mercilessly, terming the divinity of Jesus and the sanctity of the Bible the stuff of credulity and Freemasonry thus a more viable religious alternative for men of reason.40 The Age of Reason succeeded in so angering the Evangelical opposition that the Second Great Awakening can in some important respects be credited to Paine and providence! Most of Paine’s powerful friends in Washington, President Thomas Jefferson among them, advised against publishing such a religious (read Masonic) tract, on the grounds that, in the interest of social order, the common man should not be made privy to the “heretical” beliefs of the aristocracy. In hindsight, Paine would have been wise to choose a more discreet medium, and while The Age of Reason sold well, it ended the career of one of America’s most famous and influential patriots and propagandists for democratic change. Strangely, it does not appear that Paine was a Mason, only that he thought Masonry comparable to sun or nature worship and thus preferable to its “bastard child,” Christianity (son worship per se). That from a distance he waxed rhapsodic on the future of Masonry in America is telling.41

Prince Hall is another poignant example—unable to become a Mason through the normal “American” channels because of his race, in the end he gained entrance into the order by going over heads to obtain a charter from the Grand Lodge in England. (Mormon leadership also flirted with the idea of petitioning British Masonry for a charter but decided against this course largely because it seemed fraught with compromise and thus tantamount to mixing hair and wool.) Hall’s African Lodge, by all accounts, offered middle-class black men like himself a ritual gathering place where not only dreams of economic advancement but a strong desire to join the ranks of America’s white middle class might be realized. Ironically, Prince Hall Masons discriminated against darker-skinned applicants, especially the poor black masses, catering exclusively to black males of unquestionable bourgeois sensibility.42 To the great relief of the order—one presumes—the Morgan affair had almost no effect on African-American Masonry. The great bulk of anti-Masonic polemic would be directed entirely at white fraternal association, the Antimasonic Party operating largely under the (false) presumption that middle-class blacks (whether members of a Masonic lodge or not) posed no threat to democracy, perhaps because they were not expected to play a significant role in American society to begin with (p. 36). That said, the inconspicuous nature of Prince Hall Masonry served American Masonry very well, keeping the vision and the rituals alive during the difficult days—indeed years—that lay ahead.

And so, not too far down the road from Batavia, in Palmyra, a New Yorker unlikely to gain entrance to the lodge through the regular channels would follow his own star, publishing a Masonic monitor and discreetly calling it the Book of Mormon, a literary springboard for yet another democratization of manhood in the spirit of Morgan and others. A cruel irony, Smith not only shared Morgan’s widow but eventually his fate, murdered by Masons and others who dressed mockingly in Indian costume and got off scot free. Not unlike Prince Hall, the founder of Mormonism also found himself on the outside peering in merely because of a physical handicap. Of New England stock and Masonic pedigree, he would not be denied his birthright as an American male and took the necessary steps to correct this—going over heads and crossing both ocean and channel, going not to the Jerusalem Lodge in London for his charter but to Jerusalem itself and the God of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and, ultimately, the Son of God for permission to start anew. Finally, not unlike Oliver, he hoped to reunite and revitalize American Masonry according to a Christian-Masonic vision, but along Templar lines in the broadest, most advanced, and hermetic sense, knitting the York and Scottish rites together into a seamless whole in the hopes of bringing about a union of Masonry and Christianity writ large.