THE HISTORIANS OF KING PHILIP’S WAR often referred to three native camps located in Nipmuc country that were each used extensively throughout the war as places of shelter and defense. These sites, called Wachusett, Menameset, and Quabaug Old Fort, were strategically located between Narragansett and Wampanoag territory to the south, and the Connecticut River Valley Indians to the west. As such, they were centers of command that played host to an extraordinary mix of Native American peoples throughout King Philip’s War.

The first and most vaguely defined site was described by William Hubbard when he reported that the Narragansett, after their defeat at the Great Swamp Fight, marched north into Nipmuc country “toward Watchuset Hills meeting with all the Indians that had harbored all winter in those woods about Nashaway.”1 This same camp at “Watchuset Hills” was nearly attacked by Major Thomas Savage in March 1676, but the assault was called off when Savage marched to the Connecticut River to counter threats of an attack there.2 Mary Rowlandson was held captive at or near this same camp in April 1676; local historians place this site “on the western side of Wachusett, probably Princeton.”3 Despite these several references, the precise site of the Nipmuc’s “Wachuset Hills” camp is today unknown, though hikers and skiers undoubtedly trace the same paths that Philip and his armies walked in 1675 and 1676.

Menameset (sometimes written as Wenimisset) was perhaps the most important Native American military site of the war, and the site to which the Nipmuc fled immediately after the outbreak of hostilities in 1675. Menameset comprised three villages, described in detail by J. H. Temple in his History of Brookfield, Massachusetts. All three villages were seated on the eastern bank of the Ware River, in the northern section of New Braintree and the southern section of Barre.

The most southern (or “lower”) site of Menameset is marked by a small, inscribed stone situated on the north side of Hardwick Road just east of Wenimisset Brook. Behind the marker is a flat plain of perhaps five acres, bordered by the brook on one side. Historians George Ellis and John Morris believed that the encampment was about twenty rods from the Ware River,4 but modern historians are less convinced that the correct site has been discovered.5

Menameset’s “middle village” (heading upstream), thought to be another campsite that King Philip visited in 1675,6 is located north of Hardwick Road about a mile northeast of the first site. It can be found by walking north through North Cemetery at the “bend” in Hardwick Road and continuing through a small pine grove behind the cemetery. There one finds a perfectly flat plain of about forty acres stretching back to the Ware River, large and ideally suited for a camp, where numerous native artifacts have been found.

The northernmost camp (“upper village”) of Menameset is today a sand pit, located in the town of Barre just west of Airport Road, about seven-tenths of a mile from the New Braintree border. There, the Ware River forms a double oxbow, and it was in the lower bend of about nine acres that the camp probably sat.7 Many historians think it was here that Mary Rowlandson was held captive from February 12 to February 28, her third remove,8 and that this would be where she met Robert Pepper, who had been captured at Beers’ Ambush. Any evidence of Native American activity has been generally destroyed by the work of backhoes.

Temple also discussed in detail the sites of several other important Nipmuc villages, including their stronghold known as Quabaug Old Fort. Also called Ashquoach, this village has traditionally been located on Indian Hill, north of Sherman’s Pond (“Great Pond”) in Brimfield, Massachusetts, a short distance from the Warren town line.9 Levi Badger Chase, in his description of the Bay Path, noted the importance of Ashquoach’s location:

Four paths are mentioned as diverging from this point. The western path from Quabaug “Old Fort” passed north of Steerage Rock to the bend in Quabaug River; parting there, one branch kept south of the river, to Springfield, the other crossed the river into Palmer and on to the Great Falls of the Connecticut, now Holyoke City. Another path ran to the falls of Ware River; and still another to the Indian village of Wickabaug, now West Brookfield.10

Temple noted that Ashquoach was distinguished for its great cornfields and strong defenses, situated as it was at the highest point of the hill with an open view in all directions.11 It is thought that King Philip stopped here on August 5, 1675, on his flight from the Nipsachuck Swamp Fight, but finding the fort deserted, marched to Menameset where Nipmuc warriors were preparing for war.12 Today, the traditional site of Ashquoach can be found on the southeastern knoll of Indian Hill, on a flat spot beside the steep eastern slope, north of the split between Marsh Hill Road and Brookfield Road. The site is on private land and partially fenced.

More recently, in Wheeler’s Surprise: The Lost Battlefield of King Philip’s War, author Jeffrey Fiske has reexamined historical records and concluded that Ashquoach was most likely located “on a hill northwest of Quaboag Pond” in present-day Brookfield. Fiske believes the confusion has come about from use of the term “Connecticut Path” to describe not one but three ancient paths in Massachusetts.13

Wekabaug, not central to the war but the single largest Nipmuc camp in the area, was built on a bluff at the southerly end of Wekabaug (Wickaboag) Pond, adjacent to the pond,14 in present-day West Brookfield. This camp was visited by Massasoit in 1657 and apparently pledged allegiance to him at the time. Related sites include a camp located about three-quarters of a mile southeast and just across the river, a burial spot on a bluff at the northeasterly end of Wickaboag Pond, and two camps on Quaboag Pond in Brookfield. One of these latter camps was located at the fork of the Seven Mile Brook and Five Mile Brook, formerly a steep hill leveled during construction on the East Brookfield railroad station and freight yard.15

Massachusetts Bay had been involved in King Philip’s War from its outset, sending troops to assist Plymouth Colony at Swansea and to meet with the Narragansett in Rhode Island. On July 14, 1675, however, the war took on new meaning for officials in Boston when violence spread into Massachusetts Bay Colony itself. A Nipmuc band under Matoonas killed five or six residents of Mendon at work in the fields. The Nipmuc did not press their attack, fleeing instead into the surrounding woods. Hubbard noted that the settlement, “lying so in the Heart of the Enemies county, began to be discouraged,” and shortly after was abandoned.16

That winter the Nipmuc returned and burned the deserted settlement to the ground. The Reverend Increase Mather, in a rare attempt at humor, spoke to the spiritual health of the colony when he wrote that in “Mendam, had we mended our ways as we should have done, this misery might have been prevented.”17 Very little is known about the actual assault, nor have all the names of the victims been identified. One frustrated Mendon historian complained that the town records do not furnish “a single item of intelligence”18 concerning King Philip’s War. Based on land records, antiquarians have suggested an approximate location of the attack, and a marker at Providence Road and Hartford Avenue that designates the site reads:

NEAR THIS SPOT

THE WIFE AND SON OF

MATTHIAS PUFFER

THE SON OF JOHN ROCKWOOD

AND OTHER INHABITANTS OF

MENDON

WERE KILLED BY NIMUCK INDIANS

14 JULY 1675

THE BEGINNING OF KING PHILIP’S WAR

IN THE COLONY OF MASSACHUSETTS

In addition to this marker, the state of Massachusetts has designated the site of Mendon’s First Meetinghouse on Route 16 at Main Street. This structure was built in 1668 and lost in the general destruction of 1676.

In 1967, the town celebrated its three hundredth anniversary by issuing a commemorative coin, the reverse side of which depicted the massacre.

On August 2, 1675, one of the war’s best-known and most devastating ambushes, Wheeler’s Surprise, took place within the bounds of present-day New Braintree. The ambush occurred just as Philip was making his escape from English soldiers in the Nipsachuck Swamp and heading north to join his Nipmuc allies.

Captain Edward Hutchinson had been assigned the unenviable task of negotiating a treaty with the Nipmuc, in part because “he had a very considerable farm thereabouts, and had occasion to employ several of those sachems there, in tilling and plowing his ground, and thereby he was known by face to many of them.”19 Such a treaty, more threat than negotiation, was designed to keep the Nipmuc from joining Philip. In retrospect, the mission was doomed to failure: Mendon, Massachusetts, had already been destroyed by Nipmuc warriors, and Philip had just slipped past the English at Pocasset and was on the move. At the time, however, colonial officials still held that Wampanoag aggression could be contained in southern New England.

Hutchinson was experienced in this type of highly charged negotiation, having met with Narragansett leaders in June and July 1675 to force their signatures on a treaty of neutrality. He was accompanied in this new effort by three friendly Indians; three men from nearby Brookfield, including Sergeant John Ayres; Ephraim Curtis, an able and courageous scout who built the first home at Quinsigamond, or present-day Worcester; and Captain Thomas Wheeler, whose mounted force consisted of twenty men.20 Hutchinson, Wheeler and his troops had marched from Cambridge to Sudbury on July 28, 1675, and then west into Nipmuc territory. Most of the soldiers under Wheeler were from Billerica, Chelmsford, and Concord, and did not know the area into which they were riding.

When Wheeler and the party arrived at Brookfield (called Quaboag Plantation, now the Foster Hill section of West Brookfield) on Sunday, August 1, Curtis and three others were sent to arrange a meeting with the Nipmuc. Curtis discovered the Nipmuc at a camp about ten miles from Brookfield and drew from them a promise to meet with Hutchinson the following morning at 8 AM. The designated rendezvous spot was “upon a plain within three miles of Brookfield,”21 often thought to be the small plain at the intersection of Shea and Madden Roads in West Brookfield.22 When Hutchinson’s party arrived at the appointed hour there were no Nipmuc to be found.

This location can be visited today, though there is little left resembling what Hutchinson and Wheeler might have seen. The site was examined as long ago as 1871 by historian Ebenezer Peirce, who wrote:

The scene was almost entirely changed from that of one hundred and ninety-six years before. True, the pond [Wickaboag Pond] occupied the site it did then, and the soil of the plain was yet there, but all else, how completely changed! I suppose that I passed over the identical ground on which it was proposed to meet and make a new treaty with the Indians.23

Upon reaching this location, the men debated among themselves whether to proceed with the mission or return to Brookfield. Captain Wheeler, who would survive the ensuing ambush and write a firsthand account not many months later, noted:

But the three men who belonged to Brookfield were so strongly persuaded of their freedom from any ill intentions toward us . . . that the said Captain Hutchinson, who was principally intrusted with the matter of Treaty with them, was thereby encouraged to proceed and march forward towards a Swamp where the Indians then were.24 When we came near the said Swamp, the way was so very bad that we could march only in a single file, there being a very rocky hill on the right hand, and a thick swamp on the left, in which were many of those cruel blood-thirsty heathen, who there way laid us, waiting an opportunity to cut us off; there being also much brush on the side of the said hill, where they lay in ambush to surprise us. When we had marched there about sixty or seventy rods, the said perfidious Indians sent out their shot upon us as a shower of hail, they being, (as was supposed,) about two hundred men or more.25

Eight English were killed immediately or wounded and left for dead, including all three men from Brookfield who had encouraged Hutchinson to push on. Five others were wounded but escaped, including Wheeler, Wheeler’s son (who saved his father’s life), and Hutchinson. Hutchinson died from his wounds soon after and was buried in Marlboro, Massachusetts.26

When the party attempted to retreat, the Indians prevented them from going back the way they came, forcing them instead to retreat by clambering up a “steep and rocky hill.”27 Wheeler added that “we returned to the town as fast as the badness of the way and the weakness of our wounded men would permit, we being then ten miles from it,”28 and also noted that “none of us knew the way, those of the town being slain; and we avoiding any thick woods, and riding in open places to prevent the danger by the Indians.”29

There are the essential facts of the ambush and retreat as they have been handed down through Wheeler’s firsthand account. Ever since, historians and antiquarians have speculated as to the precise location of the attack. In a footnote to the 1843 publication of an oration he delivered in 1828, Joseph Foot suggested that the precise site would never be determined:

The spot where Captain Hutchinson and his company were attacked cannot be ascertained. There are two places, which tolerably answer the description given by historians. The one is near the line of Brookfield and New Braintree. The other is nearly two miles north of this line. Without records and with contradictory traditions it is probably impossible to determine with certainty at which place the onset was made.30

Foot’s conclusion notwithstanding, speculation on the site of Wheeler’s Surprise became something of a heated debate in the late nineteenth century, with so many papers being delivered on the subject that one historian felt a complete bibliography was needed.31 However, all the debate focused around two particular locations—not necessarily consistent with Foot’s theory—both of which can still be investigated by historical sleuths interested in determining for themselves the true location of Wheeler’s Surprise.

In 1884, the Reverend Lucius R. Paige published a paper in the New England Historic Genealogical Register entitled “Wickaboag? Or Winnimisset? Which Was the Place of Capt. Wheeler’s Defeat in 1675?” In it, Paige made the case for Wheeler’s Surprise having occurred in Winimisset Meadows, somewhere along a mile stretch east of the Winimisset Brook, just west of the steep hill rising toward Brookfield Road. Paige knew this area well “because his grandmother in her girlhood resided on the border of the Winimisset (or Meminimisset) Valley . . . and because he saw it so often when he was a boy.”32 Today that site is along Slein Road, perhaps near an A-frame house located about one-half mile north of the intersection of Wine Road. (This site is referred to by Paige as the Fay Farm or Brookside Farm.) A bird’s-eye view of the area can be seen from a stone marker commemorating Wheeler’s Surprise, located on West Road, three-tenths of a mile north of Unitas Road. The marker reads:

SOMEWHERE WITHIN 1/2 MILE

ALONG THE BASE OF THIS HILL

CAPT. EDWARD HUTCHINSON AND

HIS COMPANY WERE ATTACKED

BY INDIANS LYING IN AMBUSH

AUG. 2 1675 AND HE AND MORE

THAN ONE HALF HIS MEN SLAIN

OR WOUNDED.

The state of Massachusetts has indicated this same general area on a marker located on Route 67 (Barre Plains Road) near Thompson Road.

Paige’s argument relied on an interpretation of Wheeler’s report that his party was ambushed in the same swamp in which Curtis had met with the Nipmuc the prior day, “about ten miles north-west from us,”33 according to Wheeler, or about “eight miles from Quabouge,”34 according to Curtis. Winimisset (or Wenimisset) Meadows is eight to ten miles from Foster Hill, depending upon the route taken. This location was bolstered by William Hubbard’s history, in which he reported that Wheeler’s party was ambushed “four or five miles”35 from the appointed rendezvous place; Winimisset Meadows is four or five miles from the plain at the head of Wickaboag Pond. In addition, local tradition had long indicated Winimisset Meadows as the site of Wheeler’s Surprise.

In 1893, nine years after Paige made his case for Winimisset Meadows, a map entitled “A New Plan of Several Towns in the County of Worcester,” prepared by General Rufus Putnam and dated March 30, 1785, was discovered at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The map, which measured twenty by twenty-eight inches and covered an area of about 450 square miles, included the towns of Rutland, Oakham, Hardwick, New Braintree, Brookfield, and Warren, as well as parts of about thirteen other nearby towns. The map had been given to the historical society on April 9, 1791, and was accidentally bound into a folio volume entitled Atlas Ameriquain Septentrional and, hence, lost for over a century.36 Designated on this map in the general vicinity of the site indicated by Paige was the note: “Hutchinson & Troop Ambushed between Swamp & Hill.”37 This map, prepared by an esteemed Revolutionary War soldier, a noted civil and military engineer, and a man who spent part of his childhood in New Braintree, seemed to prove Paige’s conclusion. Paige “expressed his satisfaction in the discovery of the Putnam map, inasmuch as it so fully coincided with his own opinion . . . [and] if not full proof of the correctness of his own theory, [it was] at least a very respectable precedent.”38

Several important issues remained, however, and these were tackled by J. H. Temple in his History of North Brookfield, Massachusetts, published in 1887 after Paige’s publication but before the discovery of Putnam’s map. Temple offered the opinion that Wheeler’s Surprise occurred in a more southerly location, only a few miles north of Wickaboag Pond, between Mill Brook and Whortleberry Hill. As part of his research, Temple “traversed the valley from Barre Plains to Wekabaug pond”39 but could find no location in Winimisset Meadows matching Wheeler’s description of a “narrow defile.” Further, Temple did not believe that the Nipmuc would endanger their own camp by setting an ambush so close to it.

Temple then turned to the testimony of two Indian guides in Wheeler’s party. One, James Quannapohit, said that Menemesseg (another name for Winimisset; neither term was ever used by Wheeler in his report) was “about eight miles north from where Capt. Hutchinson and Capt. Wheeler was wounded and several men with them slain.”40 George Memicho, who was taken captive in the ambush, said that he was taken to a camp “six miles from the swamp where they killed our men.”41 Temple believed that both descriptions pointed to a location south of Winimisset Meadows and not far from the head of Wickaboag Pond. In fact, Temple noted, if William Hubbard’s estimate of Wheeler and his party riding four to five miles were applied to their starting location at Foster Hill, this would also point to his more southerly location.42

What sealed this new location (sometimes referred to as the Pepper farm) for Temple, however, was his identification of a spot in “very complete agreement of existing conditions with all the details given in Capt. Wheeler’s Narrative.”43 That spot, which is nearly unchanged today from the engraving shown by Temple in his History of North Brookfield, is located on private land off Barr Bridge Road along Mill Brook. A walk along this hillside, which is no longer particularly rocky, gives one a good sense for how an ambush might develop, how difficult the defile between the hillside and swamp might have been to travel, and how impossible it would have been to escape on horseback in any direction but up and over the hill.

To the modern historian, both sites are interesting but neither conclusive. Paige’s location carries the weight of tradition, made an even less reliable source than usual in New Braintree because nobody lived there at the time of the ambush. There is, however, a tantalizing note from Captain Samuel Moseley written to Governor Leverett from Lancaster on August 16, 1675, in which Moseley and about sixty men

marched I(n) company with Capt. Beers & Capt. Lathrop to the Swamp where they left me & took their march to Springfield and as soon as they ware gone I took my march Into the woods about 8 miles beyond the Swamp where Capt. Hutchinson and the rest were that were wounded & killed.44

If Moseley knew the location of the ambush, then perhaps it was common knowledge to many soldiers stationed in the area. This would bolster tradition as a historical source despite New Braintree’s lack of settlement in 1675. Paige also has General Putnam’s map supporting him, but Putnam prepared the map more than a century after the event and himself relied on local tradition. Perhaps most damaging to Paige is that no location can be found which resembles even vaguely the one described by Wheeler. Modern historians believe that the swamp along Winimisset Brook was closer to the hillside in former times, but whether it ever matched Wheeler’s description is unknown. In 1899, D. H. Chamberlain investigated Winimisset Meadows, taking six trips on foot, horseback, or wagon and making ten separate visits to particular points. He was, even a century ago, unable to find a location matching Wheeler’s description.

Temple has in his favor the discovery of a location that very closely matches Wheeler’s report. In addition, local tradition also sides with Temple; older citizens of New Braintree referred to the Pepper farm location as “Death Valley.” The weaknesses in Temple’s arguments are Hubbard’s contention that Wheeler’s party rode four to five miles from their first rendezvous point, near the head of Wickaboag Pond, which would place them eight to nine miles from Foster Hill.45 Also, Wheeler says that his party retreated ten miles from the scene of the ambush back to Foster; even riding a circuitous route through North Brookfield to avoid ambush, it is difficult to find ten miles between Temple’s ravine and Foster Hill.

George Bodge, writing in 1906, found merit in both arguments and noted that “both Paige and Temple are eminent authorities in antiquarian research; both reason from the same evidences in general . . . I am free to say that reading the arguments of both again and again, I am unable to decide which is the most probable site of the encounter.”46

Some historians, including Chamberlain, have virtually dismissed the use of mileage, arguing that the distances given were estimates made under extreme duress. Others, like Louis Roy, have guessed at the best path between Brookfield and the Nipmuc camps at Winimisset and, by examining a topographic map, determined the location of the ambush. Roy believed that Wheeler’s party traveled the Bay Path and that the ambush occurred on present-day Padre Road, about two-tenths of a mile south of the split from West Road.47

Of course, the real surprise in Wheeler’s Surprise for modern historians may be that we have completely missed the route taken by Wheeler’s party. It is possible that, having left the first rendezvous point, Wheeler and his men rode to the east of Whortlebury Hill, along the high land of West Brookfield Road. They may have taken this route specifically to avoid ambush along the more heavily traveled Bay Path, or because the distance was shorter, or because the terrain was better for a large group on horseback.48

Local historian Jeffrey Fiske, in his thoughtful and thorough Wheeler’s Surprise: The Lost Battlefield of King Philip’s War, has taken a careful look at the information and misinformation surrounding 1) the destination of Wheeler and Hutchinson; 2) their route of march; and 3) how their distance was calculated and reported. Fiske concludes that, “while the ambush sites suggested by Josiah Temple and Dr. Louis Roy are incorrect,” and the general area suggested by Lucius Paige is a reasonable estimate for the location of Wheeler’s Surprise, “I have not been able to absolutely identify the ambush site.”49

Two rumors had surfaced in the distant past concerning Wheeler’s Surprise. One concerned Wheeler’s sword, which was said to have been discovered in Winimisset Meadows. The other had to do with a pile of horse bones uncovered in the same location. Both are unsubstantiated and add only color to our knowledge of Wheeler’s Surprise, which remains nearly as much a mystery today as it was a century ago.

When Captain Thomas Wheeler and his remaining men fled the ambush at New Braintree, they sought safety at the English settlement of Quabaug, now the Foster Hill area of West Brookfield. Quabaug had been settled in 1660 by men from Ipswich, Massachusetts. At the time of King Philip’s War, it was an isolated farming settlement of barely twenty homes.50 Its closest neighbor was Springfield, a day’s journey to the west. Douglas Leach suggests that “indeed, scarcely a town in all of Massachusetts could claim the dubious distinction of being more isolated than Brookfield.”51

The Nipmuc used this flaming cart, filled with birch bark, straw, and powder, in an unsuccessful attempt to dislodge the English from the Ayres garrison. (Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University)

The surprise return of Wheeler and his exhausted troopers from their disastrous meeting with the Nipmuc alerted the settlers at Quabaug to danger. The frightened inhabitants abandoned their homes and fled to the house of Sergeant John Ayres. (Ayres had accompanied Wheeler and Hutchinson on their mission to parley with the Nipmuc, and for his efforts was lying dead at the New Braintree ambush site.) In all, eighty people gathered in this one home and prepared to defend themselves against the Nipmuc assault. Henry Young and Ephraim Curtis immediately set out on horseback for Marlboro but soon met hostile Nipmuc. They fled back to the garrison and shortly thereafter the assault began.

The August 1675 siege of Brookfield would last almost three days and become one of the most dramatic military engagements of the war. Upon their arrival at Quabaug, the Nipmuc warriors under Muttawmp immediately set fire to all of the structures except the fortified garrison. For forty-eight hours they surrounded the building and, in William Hubbard’s account,

assaulted the poor handful of helpless people, both night and day pouring in shot upon them incessantly with guns and also thrusting poles with fire-brands, and rags dipped in brimstone tied to the ends of them to fire the house; at last they used this devilish stratagem to fill a cart with hemp, flax and other combustible matter, and so thrust it back with poles together sliced a great length, after they had kindled it; But as soon as it had begun to take fire, a storm of rain unexpectedly falling, put out the fire, or else all the poor people, about seventy souls, would either have been consumed by merciless flames, or else have fallen into the hands of their cruel enemies, like wolves continually yelling and gaping for their prey.52

The English in the Ayres garrison responded as best they could, but the scene must have been chaotic and terrifying. Henry Young ventured too close to a window and was mortally wounded. A son of Sergeant William Pritchard attempted to secure desperately needed supplies from a nearby building, perhaps his own residence on the first lot east of Ayres’ garrison, but was captured and killed. For intimidation, the Nipmuc mounted Pritchard’s head on a pole. (Sergeant Pritchard himself had been killed at Wheeler’s Surprise). Thomas Wilson, one of the earliest English settlers at Quabaug, was shot through the jaw while attempting to secure water from a well not far from the garrison. Amidst this death and destruction there was also life, however, as two sets of twins were reported born during the siege.53

The English were surrounded but not completely helpless. They returned fire and continually thwarted Nipmuc attempts to set the garrison aflame. Reports of eighty Nipmuc killed were undoubtedly inflated,54 but Muttawmp and his warriors did not go without loss. Indeed, Ephraim Curtis was able to find enough weakness in the siege line to crawl past the Nipmuc on August 3 and make his way by foot the thirty miles to Marlboro.

Major Simon Willard and his forty-eight troopers55 were conducting operations west of Lancaster and arrived first at Quabaug. Willard, who at seventy years of age was the chief military officer of Middlesex County, had heard reports of the Nipmuc attack from people traveling along the Bay Path. He and his men rode the thirty-five or forty miles to Brookfield and arrived after nightfall on August 3,56 where they charged past the Nipmuc sentries, whose warning shots went unnoticed. Increase Mather wrote:

the Indians were so busy and made such a noise about the house that they heard not the report of those guns; which if they had heard, in all probability not only the people then living at Quaboag, but those also that came to succor them had been cut off.57

Willard’s party58 rode almost to the door of the Ayres garrison before they were spotted. With their arrival, the Nipmuc fired the remaining buildings and broke off the siege. Soon after, colonial reinforcements arrived, swelling the ranks of men under Willard to 350 English plus the Mohegan that had pursued Philip so successfully at Nipsachuck. Willard would stay for several weeks to direct military activity in the area, but the residents had little reason and little hope of real security, so the settlement at Quabaug was abandoned.

The landmarks related to the original Quabaug Plantation settlement are well marked along the north side of Foster Hill Road in present-day West Brookfield. Much of the site today is a large, open field. Traveling west, the first marker (set in a stone wall near a more modern home) designates the Ayres garrison, followed by a more elaborate memorial to John Ayres and a small stone marking the well at which Major Wilson was shot. Further west, still on the north side of Foster Hill Road, is a stone indicating the location of the first meetinghouse, burned in 1675, and a second built in 1717. The plantation’s burial ground, dated 1660–1780, is designated to the northeast of the meetinghouse location.

Foster Hill Road in West Brookfield, Massachusetts, is the site of Quabaug Plantation, attacked and destroyed by the Nipmuc in August 1675. The large memorial on the right designates the site of the Ayres garrison. (Eric Schultz)

The precise site of the Ayres garrison was apparently in some dispute in the early nineteenth century. In 1843 Joseph Foot noted:

There has been of late years no small disagreement respecting the place, where the fortified house stood. Some have attempted to maintain that it was northeast of Foster’s Hill. But as no satisfactory evidence in support of this opinion has been found, it is to be regarded as unworthy of credence. There are several weighty reasons for believing, that it stood on a hill. 1. The principal English settlement was there. 2. The meeting-house which was burned by the Indians was there. 3. In the account of the attack on the fortification a well in the yard is mentioned, and a well has been discovered near the north west corner of Mr. Marsh’s door yard, of which the oldest inhabitants can give no account except as they have been told, it belongs to the fortified house. 4. At a distance of a few feet north of the well the ground when cultivated as a garden was unproductive. As the soil appeared to be good, it was difficult to see any reason for the barrenness. On examination however it was found that a building had stood on the place. Several loads of stone, which had formed a cellar and chimney were removed, amongst which various instruments of iron and steel were found. 5. There is a hill directly west of this place, which corresponds sufficiently well with the descriptions of that, down which the Indians rolled the cart of kindled combustibles. There is then good reason to conclude that it stood between Mr. Marsh’s house and barn.59

This beautiful, detailed engraving shows the assault on the Ayres garrison, which lasted for three days and resulted in the abandonment of Brookfield. (Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University)

A state marker on Route 9 at the boundary of Brookfield and West Brookfield encapsulates the whole grim story of Brookfield’s early years in a few short lines:

BROOKFIELD

SETTLED IN 1660 BY MEN FROM

IPSWICH ON INDIAN LANDS CALLED

QUABAUG. ATTACKED BY INDIANS

IN 1675. ONE GARRISON HOUSE

DEFENDED TO THE LAST. REOCCUPIED

TWELVE YEARS LATER.

On August 24, 1675, just a few weeks after the siege of Brookfield, the English held a council of war at Hatfield to address the growing native presence at the Norwottock village, located on a bluff along the western bank of the Connecticut River above Northampton. A force of one hundred men commanded by Captains Thomas Lathrop and Richard Beers was ordered to surprise and disarm these natives, none of whom had committed any hostilities against the English. Divining English intent, the Norwottock fled the camp just before Lathrop and Beers arrived on the morning of August 25. Finding the native fires still smoldering, the English sent a portion of their troops to defend Hatfield while the remainder set off in pursuit of the natives.

A mile south of present-day South Deerfield, near the rise known as Wequomps (present-day Sugarloaf Mountain), colonial soldiers overtook the Norwottock, who dashed into present-day Hopewell Swamp. There they set an ambush for the English troops. Mather reported that

on a sudden the Indians let fly about forty guns at them, and was soon answered by a volley from our men; about forty ran down into the swamp after them, poured in shot upon them, made them throw down much of their baggage, and after a while our men after the Indian manner got behind trees, and watched their opportunities to make shots at them.60

While the exact location of the battle is unknown, Hopewell Swamp in South Deerfield, Massachusetts, shown circa 1906, was the location of the so-called Battle of South Deerfield, a three-hour skirmish that Puritan commentators fashioned as a great victory for the English army. In reality, it turned the peaceful Norwottock against the colonists and cost the English nine soldiers. (From King Philip’s War, George W. Ellis and John E. Morris, 1906)

The fight lasted three hours. The English lost nine men and the natives were said to have lost twenty-six,61 probably an exaggeration designed to turn the first military engagement in the Connecticut River Valley into a desperately needed English victory. The real result of this Puritan-styled “Battle of South Deerfield” was to turn the neutral Norwottock into deadly enemies.Writing in 1872, J. H. Temple discovered a location that met all the particulars of the Battle of South Deerfield. The spot was located about a quarter mile south of Sugarloaf Mountain where the old Deerfield trail skirted the edge of Hopewell Swamp. Here, Temple wrote, was a ravine that allowed the natives good cover, the ability to fire up both sides of the bluff, and an excellent retreat route. Temple even made an engraving of the location.

Today local tradition places the battle in Whately, Massachusetts, though there is no agreement as to the precise location. The swamp south of Sugarloaf Mountain is quite large and has been altered considerably over the years by drainage, industry, and the construction of homes. There are many spots that would seem to match Temple’s description, and it seems unlikely that we will ever have more than a general sense as to where the battle took place.62

Squakeag, now Northfield, was located a few miles north of Deerfield near the present-day New Hampshire border. Barely three years old, Northfield, as described by Ellis and Morris, consisted of “some seventeen thatched cabins, a palisade of rough logs eight foot high set upright in the ground and pierced with loopholes, and a log fort and church.”63 The most far-flung of the Connecticut Valley settlements, Northfield was generally isolated from the violence that had occurred in Brookfield, Whately, and New Braintree, and in the Plymouth Colony settlements farther south.

On September 1, 1675, sixty natives attacked and burned buildings and barns in Deerfield. When the inhabitants of Northfield awoke on Thursday, September 2, they were still unaware of this attack. Heading off in pursuit of their daily activities, the Northfield settlers were suddenly assaulted by a mixed band of Pocumtuck and Nashaway led by Monoco. Eight English were killed. The settlers rushed from their houses and fields to the stockade, watching as their homes went up in flames.

Massachusetts Bay authorities decided to evacuate Northfield immediately. On Friday, September 3, thirty-six mounted men and one ox team under the command of Captain Richard Beers of Watertown, Massachusetts, began the thirty-mile march from Hadley. Unable to reach Northfield before sundown, Beers and his men camped three miles south of the town, perhaps near Four-Mile Brook.64

On Saturday morning, September 4, Beers left his horses under guard at the camp and began the short march to Northfield. His decision to approach the town by foot may have indicated that he expected to meet resistance, but Beers did not take the usual precaution of sending scouts and flankers to protect the main force. In addition, Beers made no attempt to alter his route from the usual approach to Northfield, along the high plain.

Marching north, the English troops kept to the high way65 until they sighted Sawmill Brook, which flowed through a ravine still thick with summer growth. (This main path to the settlement was probably to the east of present-day Route 63, on slightly higher ground.)66 They followed along the left bank of the brook and then

attempted to cross it where a depression in the plain made a passable fordway, in order to reach the hard land south and west of dry swamp, and so come into the village near where is now the south road to Warwick.67 This was the common route of travel at the time; and the Indians knew that, as matter of course, he would take it, and made their plans accordingly. Concealed in front, and behind the steep bank below the crossing-place, on his right, they fired upon the carelessly advancing column just as the head was passing the brook, when it would have been exposed for its entire length.68

The location of the ambush is marked on the east side of Route 63, just north of the Community Bible Church. The marker reads:

INDIAN COUNCIL FIRES

TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY YARDS

EASTWARD ARE THE SITES OF THREE

LARGE INDIAN COUNCIL FIRES. THE

BEERS MASSACRE OF SEPTEMBER

4, 1676, TOOK PLACE IN A GORGE

ONE-QUARTER MILE TO THE

NORTHEAST

Sawmill Brook, shown on modern topographic maps as Roaring Brook, can be reached by a dirt road north of the marker. (The dirt road is on private property and sometimes blocked.) The precise location of Beers’ crossing is conjecture only, though one or two places seem logical. The spot where the dirt road first skirts the brook also affords an excellent view of Beers Mountain and Beers Hill, the direction in which the captain retreated.

The English were thrown into confusion by the attack but, as J. H. Temple and George Sheldon decribe the encounter, were able to fight their way out of the ravine and make a stand “towards the south end of the plain, where is a slight rise of land.”69 This plain, now called Beers Plain, is designated by a marker just a short distance north of the “Indian Council Fires” sign.70 Beers Plain runs north from this spot and west toward the Connecticut River. Temple and Sheldon believe it to have once been the site of a Native American village, “as attested by the remains of their granaries, and their large burial places.”71

As the English fell, Beers and a few survivors were able to retreat to a small ravine about three-quarters of a mile away on the southern spur of present-day Beers Mountain, sometimes called Beers Hill. Here Captain Beers was killed. Two days later his body was buried.

A marker on the east side of Route 63 near the Community Bible Church designates the general area of Beers’ last stand. The site of Beers’ grave can be found at the base of the main building of the Linden Hill School near the intersection of South Mountain Road and Lyman Hill Road. A modern stone marker indicates the burial spot. Temple and Sheldon, writing in 1875, provide a glimpse as to how the site was altered before the present stone marker was set.

The tradition which marks this as the spot where Capt. Beers was killed and buried, is of undoubted authenticity. The old men in each generation have told the same story, and identified the place. And the existence here from time immemorial of two stones—like head and foot stones—set at the proper distance apart, certainly marks the place of a grave; and the care to erect stones indicates the grave of more than a common solider. The new house of Capt. Samuel Merriman, built about 50 years ago, was set directly across the ravine, which was made to answer for a cellar by filling in the space front and rear. Capt. Ira Coy informs the writer that, before any thing was disturbed, he and Capt. M. dug into the grave. They found the well defined sides and bottom, where the spade had left the clay solid; and at the depth of about twenty inches (the shallowness indicating haste) was a layer of dark colored mold, some of it in small lumps, like decayed bones. The grave was then filled up, a large flat stone laid over it, and the hollow graded up.72

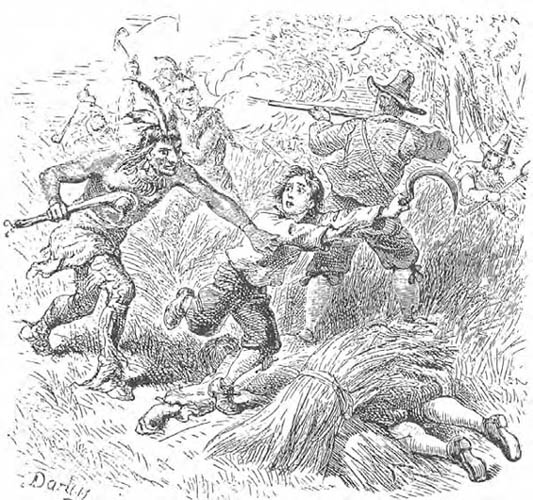

This nineteenth-century engraving may represent the ambush of Captain Beers and his men in Northfield. The movement of goods from abandoned towns not only fed the English army, but also deprived the natives of the spoils of war. (Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University)

The Linden Hill School building which now sits near the site is more recent than the one described by Temple. Beers’ grave marker has been moved from its original site, farther along the lawn to a position closer to the street.73

Temple and Sheldon also note that iron from the teamsters’ cart used by Beers was discovered in the early nineteenth century and worked up by a local blacksmith.74 In addition, local histories relate that as late as 1824, “at a sandy knoll on the west side of the road, near the place where the attack commenced, the bones of the slain are still to be seen, in some instances, bleaching in the sun. Until lately the mail route from Montague to Northfield passed over this ground.”75

The ambush was devastating to the English, who lost twenty-one men. Thirteen men, including the guard left with the horses, returned to Hadley that evening. Two more straggled in the following day, including one who had escaped from capture and reported, however accurately, the deaths of twenty-five natives during the attack.76 One man arrived confused and nearly starved six days later; he had escaped the ambush by hiding in a gully and covering himself with leaves. This gully is known as Old Soldiers Hole, a deep ravine leading from Beers Plain to the Connecticut River, one-quarter of a mile south of the lower point of Three-little Meadows.77 It is today split by Route 63 and the railroad embankment, almost directly west of Beers Hill.

On September 6, Major Robert Treat and about one hundred men rescued the anxious settlers of Northfield, still stranded in their stockade. Along the way Treat and his men found the decapitated heads of some of those slain stuck on poles, and one, wrote Hubbard, was found “with a chain hooked into his under jaw, and so hung up on the bow of a tree.”78 Such sights completely demoralized the English, who buried the dead, evacuated the town, and left it to be destroyed.

Several other sites around Northfield are associated with King Philip’s War. On Monday, March 6, 1676, Mary Rowlandson of Lancaster stayed with her Indian captors at a camp by the side of the Great Swamp described by Temple and Sheldon near “where the highway to Wendell crosses Keeup’s Brook, to the east of Crag Mountain.”79 The historians add that Philip’s Hill, “a projection of the plain which comes near to the river bank,”80 is located on the west side of the Connecticut River north of Bennett’s Meadow. This was said to be a fortified Indian site during the war and Philip’s camp for part of the winter of 1675–1676. “This hill was defended by a ditch and bank on the westerly side, and otherwise by its steep ascent; but being only about sixty feet high, it was a position of no great strength.”81 In 1897, twenty-five years after postulating the existence of Philip’s fort at this site, Sheldon reversed his position, writing, “What you see on Philip’s Hill is the work of honest John Tomkins, and not that of a fort which King Philip never built.” Tomkins, Sheldon continued, was a “hedger and a ditcher” who left a legacy of ditches around Northfield designed as the “the cheapest and most enduring fences” to hold livestock.82

On September 12, 1675, just a few days after the evacuation of Northfield, the settlement at Deerfield was assaulted for a second time by a small band of warriors who managed to burn two houses and steal several wagons full of food. Deerfield was a tempting target for the Indians because of its poor defenses and excellent fall harvest. Recognizing this, Massachusetts Bay leaders decided to evacuate Deerfield and sent troops under Captain Thomas Lathrop of Beverly, Massachusetts, to escort teamsters from Deerfield to Hadley. There, the foodstuffs could be distributed throughout the Connecticut River Valley towns during the winter months.

On September 18, Lathrop led seventy-nine men83 and a number of carts loaded with provisions on a slow march from Deerfield to Hadley. Several miles south of Deerfield near a shallow brook in present-day South Deerfield, the convoy’s lead stopped to rest and allow the teamsters in the rear time to catch up. Like Increase Mather, who describes a scene in which many of the soldiers were “so foolish and secure as to put their arms in the carts, and step aside to gather grapes, which proved dear and deadly grapes to them,”84 we can only wonder what Lathrop was thinking at the time, given the recent attacks on Deerfield and the fatal ambush of Captain Beers on a similar mission to Northfield two weeks before. Edward Everett suggested that nearby scouting activity by Captain Moseley and his troops, and the sense that one of the more difficult legs of the journey had been completed, led to carelessness:

This depiction of the massacre at Bloody Brook shows Captain Lathrop’s men marching from Deerfield and illustrates how the distance between the teamster carts made a concentrated defense against the Nipmuc ambush nearly impossible. (Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University)

Captain Moseley, who had arrived on Connecticut River three days before, was at this time stationed with his company at Deerfield, and proposed, while Captain Lothrop was on the march downward, to range the woods in search of the enemy . . . It is not improbable that Captain Lothrop and his men, relying too much on Moseley’s cooperation, proceeded without due caution. Having passed with safety through a level and closely-wooded country, well calculated for a surprise, and deeming themselves in some degree sheltered by the nature of the ground they had reached, the tradition is, that on their arrival at the spot near which we are now assembled, their vigilance relaxed. The forest that lines the narrow road, on which they were marching, was hung with clusters of grapes; and, as the wagons dragged through the heavy soil, it is not unlikely that the teamsters, and possibly part of the company, may have dispersed to gather them.85

Not only did Deerfield suffer considerable destruction during King Philip’s War, but the village would fall victim again in 1704 to a lightning raid by Indians migrating along the Connecticut River Valley to Canada.

Lathrop’s lapse in judgment would prove fatal. Muttawmp and his “multitudes”86 set upon the English in a “sudden and frightful assault,”87 killing Lathrop almost immediately. More than forty soldiers and seventeen teamsters were killed.88 Captain Samuel Moseley and his troops were patrolling nearby and dashed to the rescue, only to be drawn into the fight with taunts of “Come on, Moseley, come on. You want Indians. Here are enough Indians for you.”89 All afternoon Moseley and his men fought, losing eleven90 and coming dangerously close to being completely surrounded and destroyed, until Major Robert Treat arrived around dusk with enough reinforcements to drive Muttawmp and his men from the field.

The brook at which Lathrop and his men paused, once called Muddy Brook, was said to have turned red with English blood and has ever since been known as Bloody Brook. Today, it crosses under Main Street in South Deerfield about one mile south from the intersection of Route 5; this is said to be precisely the spot at which Lathrop passed.91

Two memorials are maintained at the site. A white marble monument was erected in 1838 and stands just south of the brook at the bend in the road near Frontier High School. The cornerstone for the monument was laid in 1835 at an occasion that brought Edward Everett, General Epaphas Hoyt of Deerfield, and about six thousand people to the site. Everett delivered his keynote address under a walnut tree just east of the monument.

The second Bloody Brook memorial, and perhaps the oldest surviving monument to veterans in America, is found about one hundred yards south of the marble monument in the front yard of 286 North Main Street. This rectangular slab is set horizontally in the ground and marks the common grave of Lathrop and the men buried there by Treat and Moseley the day following the ambush.92 This monument was moved so many times by owners of the property that in 1835 a committee of investigation was formed93 to identify the precise location of the mass grave. Guided by “tradition and some aged people”94 the committee located the spot. A contemporary account reported that the bones of about thirty men were found “in a state of tolerable preservation, but fell to pieces on exposure to the air”;95 these were all that remained of the “sixty persons buried in one dreadful grave”96 described by Increase Mather. On the same day that the English mass grave was rediscovered, the committee also reported finding a grave with the remains of ninety-six Native Americans, about a half mile distant, to the southwest of the grave of Lathrop.97 Contemporaries assumed that these natives had been killed in the fight. Edward Everett supposed that the Indian warriors

The Bloody Brook Memorial was dedicated in 1838 by the governor of Massachusetts, Edward Everett, and stands today as one of the most visible reminders of King Philip’s War. (Eric Schultz)

The site of the Bloody Brook battle, captured in this early-twentieth-century photograph, shows the crossing at North Main Street in South Deerfield, Massachusetts, and the marble monument placed in 1838. Bloody Brook is one of the most famous and best-visited sites of King Philip’s War. (From King Philip’s War, George W. Ellis and John E. Morris, 1906)

fled across the brook, about two miles to the westward, closely pursued by the American force, and here the action was probably suspended by the night. A quantity of bones, lately found in that quarter, is very probably the remains of the Indians who fell there at the close of the action.98

We will never know if Everett was correct in his assumption, but we can be sure that Moseley and Treat would have been surprised to discover that, in Everett’s nineteenth-century terms, they had become the “American force” at Bloody Brook.

Springfield’s location on the Connecticut River and at the junction of two important colonial trails made it second only to Hartford in importance among the Connecticut River Valley towns. On the eve of King Philip’s War the settlement boasted a population of five hundred English settlers scattered about four distinct villages. These included the town center; a settlement opposite the center on the west bank of the Connecticut River; Longmeadow, located four miles south of the center; and Skepnuck, situated three miles northeast of the center.

About a mile south of the center, on a bluff along the east bank of the Connecticut River nearly opposite the Westfield River, sat a palisaded Agawam Indian village. The site is today referred to as Longhill, and the village itself, Fort Hill (which is designated by a marker at the intersection of Sumner Avenue and Longhill Street99). It was established as a native village about 1650 and was made famous as the staging grounds for an Agawam-led assault on Springfield during King Philip’s War.

Fort Hill’s boundaries have never been precisely determined, but a Springfield historian’s description of the site in 1886 noted the following:

A little plateau on a prominent spur of a hill, with abrupt declination shaped liked a sharply truncated cone, afforded natural advantages for a fort. There is a deep ravine on the south side, which was probably the fortified approach to the fort. Many stone arrow-heads and hatchets have been found in this ravine . . . It has been assumed by some that only a part of the plateau was included in the fort . . . [but] it is fair to conclude that the whole brow of this hill was surrounded by a stockade.100

In 1895 local historian Harry Andrew Wright excavated Fort Hill. He discovered (among hundreds of artifacts) “the site of ten rows of lodges and two large council houses,” as well as “a pattern of post molds uncovered along the western margin of the bluff,”101 confirming that the village had been palisaded. A short distance south of the site, Wright uncovered thirteen burial sites.

More recently, William R. Young and John P. Pretola of the science museum in Springfield have studied Fort Hill.102 The site has yielded artifacts (housed in collections at the Springfield Science Museum, the Skinner Museum at Mount Holyoke College, and the Peabody Museum at Harvard University) such as a German silver-plated spoon consistent with the mid-seventeenth-century occupation of Fort Hill; “Dutch fairy pipes” from Bristol, England; finished gunflints; three good examples of Native American ceramics; and even an oyster and quahog shell, indicating contact with coastal native groups.103 More puzzling to Young and Pretola is the relative lack of structural features at the site, making it impossible to reconstruct the configuration of Fort Hill, and leaving the possibility that more of the site is still unexplored.104

Among Springfield’s most influential residents was Major John Pynchon, son of Springfield’s founder and a successful merchant who played an important role in the establishment of several Connecticut River Valley towns. Despite his business success, Pynchon was no soldier and had asked Massachusetts Bay officials on two occasions to be relieved of his post as commander of all colonial troops in the valley. Pynchon was especially at odds with the council’s military strategy, which emphasized an offensive campaign where every soldier took to the field, often leaving Springfield and nearby towns undefended.

Pynchon watched with anguish as Captain Richard Beers was ambushed on September 4, Lathrop’s troops were massacred at Bloody Brook on September 18, and Pynchon’s own mill complex in present-day Suffield, Connecticut, was destroyed on September 26. With small bands of warriors roaming the woods throughout the valley, sniping at settlers and soldiers alike, and the council pushing him to act, Pynchon knew that he must locate and engage the main body of Indians.

Also troubling to Pynchon was the suspicion that the local Agawam might not remain loyal to the English, despite their neutrality thus far. To head off any threat, Pynchon had requested that hostages be sent to the English as a sign of good faith. The Agawam balked.

A town constable of Springfield, Massachusetts, Lieutenant Cooper was convinced that the Agawam would remain loyal to the English. This conviction cost Cooper his life, and a marker on present-day Mill Street designates the spot of his ambush. (Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University)

Pynchon’s suspicions were well-founded but not strongly enough held. On October 4, 1675, he led a large force from Springfield to join troops stationed at Hadley. On the morning of October 5 this combined force attacked a large Indian camp located about five miles to the north. Springfield was left suddenly defenseless, a point not lost on the Agawam.

It would be revealed later that the Agawam had been sheltering within Fort Hill, for some period before October 5, a body of hostile warriors. On the night of October 4 as many as several hundred additional warriors had been secretly admitted into the Agawam village. With their encouragement, a plan was devised to attack Springfield the following morning, once Pynchon’s troops were well clear of the town. This plot was revealed by Toto, an Indian employed by an English family at Windsor, Connecticut. Messengers were sent to Springfield on October 5 and managed to awaken residents and gather the population in three fortified houses. A messenger was sent to Hadley to recall the recently departed troops.

Among Springfield’s three garrisons was the home of John Pynchon (once thought to be a brick house but now believed to be a wood-frame house built by his father near the corner of present-day Main and Fort Streets).105 The second garrison belonged to Jonathan Burt and stood near the southwest corner of present-day Broad and Main Streets.106 The third garrison, built in 1665, was the Ely Tavern, located on Main Street, a little south of present-day Bliss Street.107 The Ely Tavern was moved about 1843 to Dwight Street, west of State Street, and was demolished in 1900. All signs of these early garrisons have been lost to the growth of Springfield’s central business district.

When all remained quiet on the morning of October 5, Lieutenant Cooper and Thomas Miller, the town’s constable, decided to ride to Fort Hill and investigate. Cooper in particular was convinced that the Agawam would remain loyal to the English despite hostilities throughout the valley. He was wrong; only a short distance from the garrisons the two were ambushed. Miller died instantly but Cooper kept his mount long enough to warn the nearest garrison, at which point he also died. A marker on present-day Mill Street designates the spot of the ambush.

A body of warriors estimated at between one hundred and three hundred108 was hot on Cooper’s heels and immediately attacked the garrisons. Meeting with resistance, they began to fire the unoccupied structures, burning thirty-two houses and twenty-five barns.109 Had help not arrived at this point, the Reverend William Hubbard wrote, “the poor people having never an officer to lead them, being like sheep ready for the slaughter . . . no doubt the whole town [would have] been totally destroyed.”110 Major Robert Treat appeared on the west bank of the Connecticut River with troops but was unable to cross in the face of enemy fire. He still managed to distract enough of the warriors so that the destruction of the town was slowed. By the time Major Pynchon and his 190 men reached Springfield in the early afternoon, riding nonstop all day, the native forces had escaped to Indian Orchard on the Chicopee River six miles east of Springfield.111

The assault on Springfield was traumatic. Three English had been killed, great quantities of provisions were lost, Pynchon’s remaining mills were destroyed, only thirteen houses were left standing in the town center, and any sense that Springfield might offer a safe haven from hostilities was shattered. Hubbard wrote, “Of all the mischiefs done by the said enemy before that day, the burning of this town of Springfield did more than any other, discovered the said actors to be the children of the devil, full of subtlety and malice, there having been from about forty years so good correspondence betwixt the English of that town and the neighbouring Indians.”112 For the third time Pynchon asked to be relieved of his command and would soon learn that orders had already been sent appointing Major Samuel Appleton to his post.

The center of Springfield was not attacked again during the war, and the town was never abandoned. However, on March 26, 1676, a group of sixteen or eighteen settlers and soldiers under Captain Whipple, many “having most of the winter [been] kept from the public meeting on the Lords Days, for fear of the enemy,”113 were ambushed by eight warriors114 while walking to church from Longmeadow to Springfield. Two English were killed and four captured. Tradition locates the ambush in present-day Forest Park, at the southern end of Springfield, near the Pecowsic Brook.115 The following day English troops caught up with the kidnappers, who killed both children and one of the women while severely wounding the other.

Hatfield, located on the western bank of the Connecticut River opposite Hadley, had been the “west side” of the Hadley settlement until 1670, when the General Court granted its independence. Seventeenth-century Hadley

made a general picture not so different from today. The settlers viewed a wide valley, abounding in large meadows of lush native grass, good for mowing but devoid of timber except for tree clumps in swampy parts or along the river . . . The mighty Connecticut River flowed to the sea—the river bed narrower and its banks further from Main Street than they are today. The road to Northampton made the same big bend as it does today before turning up Main Street. Except that it was a narrow or path, Main Street in 1661 was, just as now, about a mile in length with a Common on the south end . . . The first houses were set back on either side and extended from the present Maple Street corner approximately to the present School Street.116

By the time of King Philip’s War, there were about fifty houses and 300 or 350 settlers in Hatfield.117

By the middle of October 1675, the lower Connecticut River Valley was alive with the activity of native warriors encouraged by their victories at Brookfield, Deerfield, Northfield, and Springfield. Major Samuel Appleton had recently taken over command of the valley troops from John Pynchon, and hardly knowing from which direction the next assault might come, divided his army among three towns. In Northampton he placed a force under Lieutenant Nathaniel Sealy, supplemented by troops under Major Robert Treat of Connecticut. In Hatfield he stationed Captains Jonathan Poole and Samuel Moseley. Meanwhile, Appleton himself commanded a force stationed at Hadley.

At noontime on October 19 the anxious waiting was over. Several fires were spotted north of Hadley. Perhaps against his better judgment, Captain Moseley sent out a scouting party of ten men who marched two miles from the garrisons and were caught in an ambush. Six men were killed, three captured, and only one returned to Hatfield.

Fearing the worst, Moseley sent to both Hadley and Northampton for reinforcements. Appleton left twenty soldiers in Hadley and crossed the river with the remainder to join Moseley. At about 4 PM a large band of warriors118 appeared at the edge of the meadows and rushed the settlement. William Hubbard, undoubtedly the recipient of a firsthand account of the battle from his neighbor, Samuel Appleton, recorded that “Major Appleton with great courage defending one end of the town and Capt. Moseley as stoutly maintaining the middle, and Capt. Poole the other end; that [the Indians] were by resolution of the English instantly beaten off, without doing much harm.”119 Appleton caught a bullet through his hat and another soldier was killed, but the force of the English volleys convinced the warriors that the town was too well fortified to defeat. After about two hours they retreated in some confusion, their first real setback in the war.

The battle at Hatfield was a turning point for the English, proving that native warriors could be repulsed if the military was prepared. In addition, Hubbard recorded, “This resolute and valiant repulse put such a check upon the pride of the enemy, that they made no further attempt upon any of those towns for the present,”120 retiring for the winter to plan their spring campaign.

After this first attack on Hatfield the settlers copied Northampton’s example and constructed a stockade, working throughout the fall and winter to encompass nearly half of the town’s existing structures.121 The wooden stockade stood ten to twelve feet high and ran four hundred feet. A 1910 history described it as follows:

The house of Fellows, Cole, and Field at the south, and several at the north, were outside. The south line of the palisades was below the Godwin lot, occupied by Rev. Hope Atherton, and the Daniel Warner allotment on the opposite side of the street. The north line was between the houses of Daniel White, Jr. and John Allis, crossing the street to include the homestead of Samuel Dickinson.122

A successful attempt was made about 1839 to trace the line of the stockade, though it is unclear from the historical material what precisely was being “traced.”123 A more recent history reported that the “two lengthwise walls of the enclosure ran parallel to Main Street, thus closing in the houses and barns on either side.”124 The southern perimeter of the stockade wall crossed at present-day 12 Main Street and the northern perimeter at 49 Main Street.125

On May 30, 1676, “a great number”126 of warriors appeared in Hatfield, burning twelve outlying structures and stealing cattle and sheep. Many of these warriors were thought to be survivors of the fight at Peskeompskut (Turner’s Falls) earlier in the month. Twenty-five men rowed across from the Hadley side to offer reinforcement but were cut off from both the stockade and a retreat to the river. Five were killed before soldiers came rushing out of the Hatfield stockade to their defense. A short time later Captain Benjamin Newberry and his troops appeared on the opposite shore at Hadley. The Indians held off Newberry’s men and continued their attack briefly but were unable to breach Hatfield’s stockade and retreated at dusk. In all, seven English were killed and five wounded.

The most devastating assault on Hatfield occurred on September 19, 1677, more than a year after King Philip’s death, when a party of forty to fifty natives attacked the town, catching the settlers completely off guard. Many of the town’s men were working in the fields or helping to raise the frame of a house outside Hatfield’s palisade, which likely was at the very end of the village street.127 Several men were shot down from the top of a house they were raising while others were carried away captive. The warriors rushed through Middle Lane (present-day School Street) and set fire to several structures. A vicious battle took place at the intersection of Middle Lane and present-day North Main Street.128 Twelve English were killed, four wounded, and seventeen kidnapped129 by this band of Canadian-bound Indians, who never attempted to breach Hatfield’s stockade. Breaking off the raid, they raced with their captives across the fields to the Pocumtuck Path. Heading north, the warriors took additional captives and caused more destruction at Deerfield.

Contrary to the belief of the English settlers, who saw Philip’s hand in every battle of the war, Philip played little part in the events in New England during the winter months of 1675 and 1676. While his precise movements are unknown, it appeared that shortly before the bloodiest day of the war, the Great Swamp Fight (at South Kingstown, Rhode Island, on December 19, 1675), expecting little assistance from the Narragansett, Philip and his men had headed northwest to seek other allies. By December 1675130 the Pokanoket sachem had settled into winter quarters as a guest of the Mahicans in Schaghticoke, New York, north of Albany on the Hoosic River. Philip’s plan, to acquire additional guns and encourage the Mahicans to take up arms against the English, apparently met with some success; a report delivered to New York Governor Edmund Andros in February 1676 indicated that Philip had gathered twenty-one hundred warriors.131

This was all the governor needed to hear. Fearing the war’s spread into New York, Andros encouraged the Mohawk—already hated enemies of the Algonquian—to attack Philip’s army. In a ruthless surprise assault late in February, the Mohawk killed all but forty of about five hundred men with Philip. A second band of about four hundred scattered.132 One historian wrote that “this was the blow that lost the war for Philip.”133 Philip hobbled back to New England, destined to spend the remainder of the war as a relatively minor figure, more hunted than hunter. Without this fresh source of ammunition and men, the native alliance began to crumble. Individual sachems, like Canonchet, would emerge as prominent military leaders, but a coordinated native war strategy would become increasingly difficult to prosecute.

Schaghticoke is an ancient Indian habitat dating back many centuries before King Philip’s War. The site of the Mahican settlement during the war is thought to be land at the crossroads of the Hoosic River and the Tomhannock Creek (the name Schaghticoke might mean “comingling of waters”), and it is here that Philip may have quartered during the winter of 1675–1676. Local legend suggests several places in Schaghticoke where an Indian battle occurred, though there is no conclusive evidence to indicate the location of the Mohawks’ surprise attack on Philip and his army. The eighteenth-century Knickerbocker mansion, on Knickerbocker Road off Route 67, is the best landmark for this area as it sits in the center of Old Schaghticoke and the ancient Indian settlements.134 The nearby Knickerbocker Family Cemetery, site of the oldest marked graves in town, is said to contain both Indian and slave burials.

A field located just before the Tomhannock Creek on the north side of Route 67 is said to be an Indian burying ground.135

This part of the Hoosic River Valley has come to be known as the Vale of Peace. It was the site of an important meeting in late 1676 (or 1677), after Philip’s death, in which Governor Andros of New York brought together English, Dutch, Mohawk, Mahican, and Algonquian refugees from New England, promising the latter a safe haven from the New England authorities demanding their return.136 An oak tree, known as the Witenagamot Oak, was planted to mark the occasion. This tree survived until 1948.137 A second oak was planted nearby in 1701. In this way Andros was able to turn enemies of New England into “New York’s staunch supporters.”138

Thomas Eames’ farm was located within the bounds of the Plantation of Framingham, on the southern slope of Mount Wayte, about seven miles southwest of Old Sudbury. On February 1, 1676, while Eames was away, the house was assaulted by about a dozen Nipmuc under Netus.139 Tradition holds that two of the children were captured at the well, and Eames’ wife attempted to fight off the attack by pouring boiling liquid (from the manufacture of soap) on her assailants.140 Netus and his men, according to Hubbard, “burned all the Dwellings that belonged to the Farm, Corn, Hay and Cattle, besides the Dwelling-house.”141 Eames’ wife and three or possibly four of their children were killed, while the rest were carried off toward Lancaster. At least one son eventually made an escape, and others of the children were ransomed. Thomas Eames lived only a few years after the tragedy, dying in 1680, and Netus was killed at Marlboro on March 27, 1676.142

On Mount Wayte Avenue in present-day Framingham sits a marker designating the location of Thomas Eames’ house. Town historian William Barry wrote in 1847 that “a partial depression of the surface, with the surrounding apple trees, still indicate[d] the spot,”143 though nothing can be seen today.

On the tenth of February, 1676, came the Indians in great numbers upon Lancaster. Their first coming was about sun-rising. Hearing the noise of some guns, we looked out: several houses were burning, and the smoke ascending to heaven. There were five persons taken in one house: the father, the mother, and a suckling child they knocked on the head: the other two they took and carried away alive. There were two others, who being out of their garrison on some occasion, were set upon; one was knocked on the head, the other escaped. Another there was, who, running along, was shot and wounded, and fell down; he begged of them his life, promising them money, (as they told me,) but they would not hearken to him but knocked him in the head, stripped him naked and split open his bowels. Another, seeing many of the Indians about his barn, ventured and went out, but was quickly shot down. There were three others belonging to the same garrison who were killed; the Indians getting up upon the roof of the barn, had advantage to shoot down upon them over their fortification. Thus these murderous wretches went on burning and destroying [all] before them.

At length they came and beset our own house, and quickly it was the dolefullest day that ever mine eyes saw.144

So began one of the great epics of colonial literature, The Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, written by the wife of Lancaster’s first ordained minister. The book, published in 1682, chronicled Mary’s ordeal as a captive of Quannopin, a sachem of the Narragansett who helped lead his people in the attack on Lancaster. Mary’s captivity lasted almost three months and took her on an arduous journey as far south as New Braintree, Massachusetts, and as far north as Chesterfield or Westmoreland, New Hampshire.145 During her captivity she suffered hunger and exhaustion, watched her youngest child die in her arms of a wound received in the attack, but also lived and worked with Quannopin, Weetamoe, and Philip—giving us one of the few glimpses of the Algonquian at war.

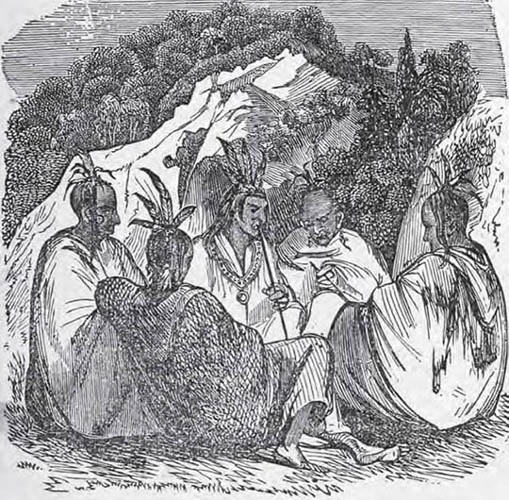

The native attack on Lancaster, shown here as it was being planned, devastated the town and led to, in Mary Rowlandson’s words, “The dolefullest day that ever mine eyes saw.” (Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University)

This marker, moved often by road crews and for a time hidden behind a stone wall, commemorates the Rowlandson garrison in Lancaster, Massachusetts. Not far away, a tall pine tree designates the precise site of the garrison, destroyed in the war. (Michael Tougias)

At the time of the attack, Lancaster consisted of about fifty families organized around six garrisons. The defense of the town was placed in the hands of fifteen soldiers, detailed to the various garrisons. Conscious of Lancaster’s exposed position and prompted by threats of impending attack, the Reverend Joseph Rowlandson had traveled to Boston to seek additional military assistance.

The assault on Lancaster came at dawn on February 10, 1675/76, and was led by Monoco. Five of the town’s garrisons held, but the Rowlandson garrison had several disadvantages upon which the natives quickly seized. First, the garrison stood on the slope of a hill, so that the natives could lie along the crest and fire continuously with little fear of being hit by return fire. More devastating, however, was a mistake made by the settlers in piling winter firewood against the loopholes in the rear of the garrison. Seeing this, the natives seized a cart from the barn and, using the same strategy as that employed at Brookfield, set its cargo of hay, flax, and hemp on fire and launched it at the garrison. Soon after, the Rowlandson garrison was in flames and its occupants were racing for other garrisons. Of ten or twelve men within the garrison, only Ephraim Roper escaped. All of the women and children were captured, including Mary Rowlandson.

The site of the Rowlandson garrison is on the adjoining field to the north of the Thayer Performing Arts Center at 438 Main Street. A dirt road off Main Street leads past the location. A white pine was planted to mark the site of the garrison, and a cemetery sits on the south side of Main Street where the town’s meetinghouse stood. No marker is evident near the pine, though just off Main Street, tucked directly behind the stone wall running along the road, is a stone marker. This marker once sat near the road, but was moved several times and eventually ended up in a spot that can only be seen by climbing on top of the wall itself. The marker reads:

IN THE FIELD NEARBY WAS

SITUATED THE GARRISON HOUSE

OF THE REV. JOSEPH ROWLANDSON

FIRST ORDAINED MINISTER OF

LANCASTER.

DURING HIS ABSENCE ON

FEBRUARY 10, 1675–76 THIS

GARRISON HOUSE WAS ATTACKED

AND DESTROYED BY INDIANS.

THE INHABITANTS WERE

MASSACRED OR CARRIED INTO

CAPTIVITY. LATER MOST OF THEM

WERE REDEEMED.

THE MINISTER’S WIFE

IMMORTALIZED HER EXPERIENCE

IN “THE NARRATIVE OF THE

CAPTIVITY AND RESTORATION OF

MARY ROWLANDSON”

PRINTED IN CAMBRIDGE,

MASSACHUSETTS, 1682.

The Algonquian were said to attack from the west of the fir tree marker, where a pond has since been dug.146

Meanwhile, the arrival of Captain Samuel Wadsworth and forty soldiers from the east spurred the natives to retreat, but not without first firing most of the outlying buildings, gathering up great stores of food and livestock, and then forcing twenty-four English captives to march with them. Total casualties for the town probably exceeded fifty.147 The survivors, under the protection of colonial troops, buried their dead, probably near where they fell. A few headed east to be with relatives, while others took refuge in the garrisons of Cyprian Stevens and Thomas Sawyer. The Stevens garrison is marked on Center Bridge Road, near Neck Road, on the south side of the North Nashua River. The marker reads:

SITE OF THE HOME

OF CYPRIAN STEVENS

IN THE ASSAULT UPON THE

TOWN, FEB 10, 1675/6, A RELIEF

FORCE FROM MARLBORO

RECOVERING A GARRISON HOUSE

BELONGING TO CYPRIAN STEVENS

THROUGH GOD’S FAVOR