The site of Massasoit’s Spring is designated by a bronze tablet at the west end of Baker Street in Warren, Rhode Island, near the banks of the Warren River.1 This was thought to be the location of Sowams, the Wampanoag sachem’s principal village. The marker reads:

THIS TABLET

PLACED BESIDE THE GUSHING WATER

KNOWN FOR MANY GENERATIONS AS

MASSASOITS’S SPRING

COMMEMORATING THE GREAT

INDIAN SACHEM MASSASOIT

“FRIEND OF THE WHITE MAN”

RULER OF THE REGION WHEN THE

PILGRIMS OF THE MAYFLOWER

LANDED AT PLYMOUTH

IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 1620

ERECTED BY THE STATE OF RHODE ISLAND

1907

There is no spring readily apparent at this location, as a wooden fence and the surrounding buildings sit virtually on the street. Several theories have been advanced throughout the years that Sowams was actually located across the Warren River in Barrington, Rhode Island, or farther south in Bristol, Rhode Island, but tradition favors this site in Warren.2

It is believed that Philip’s primary village was located south of Sowams on the eastern side of the Mount Hope peninsula in present-day Bristol, Rhode Island. This location sat on the western edge of present-day Bristol Narrows and looked directly across at Touisset Point in Swansea, just south of the English settlement. (Some writers refer to this site as Mount Hope, although it is about one and one-half miles north of Mount Hope itself.) Early in the war the colonial army built a fort on or near this site to hold the peninsula after Philip had abandoned it. Writing in 1845, local historian Guy Fessenden claimed that after a careful search he had located the remains of this fort

situated on the top of the most south-western of several hills on the north side of a cove. They consist now chiefly of the remains of the fireplace in the fort. This fire-place was made by preparing a suitable excavation and laying low stone walls at the sides and the end for which flat stones were used, evidently brought from the adjoining beach. The remains of these ruins are now beneath the surface of the ground, which at this place is depressed several inches below the average surface of the ground in the immediate vicinity. The hill is fast wearing away by the action of the water which washes its base. The wearing away has already reached the fire-place from which the charcoal and burnt stones are often falling down the steeply inclined plane beneath.3

By 1906 the sea had eroded the site completely.4

Burr’s Hill Park is located northwest of Philip’s village on present-day Water Street in Warren. The park is built on the remains of a natural gravel bank that overlooked the Warren River. In the mid-nineteenth century, workers mining gravel in the area discovered human remains and a vast array of European and Wampanoag artifacts.5 In the spring of 1913, archaeologists working under local resident and town librarian Charles Read Carr excavated forty-two Wampanoag graves.6

Despite Carr’s careful work and the obvious importance of the site, the destructive gravel mining went on and numerous private individuals unearthed and made off with important artifacts. Carr eventually struck a deal with the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad, which owned the gravel bank (and whose abandoned track still lies nearby), to ensure that all artifacts would become the property of Warren’s George Hail Free Library. Over time, pilfered artifacts were repurchased from individuals and the collection eventually came to be held at three primary locations: at the Warren library, at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology in Bristol, Rhode Island, and at the Museum of the American Indian Heye Foundation in New York.

This image of Philip appears to use Revere’s engraving as its model, right down to the designs on the sachem’s belt and crown. (Courtesy of the Collections of the Library of Congress)

The graves at Burr’s Hill were notable for the wealth of material goods they contained, most of which dated to the seventeenth century, and more particularly to the period of Philip’s sachemship.7 The cemetery’s proximity to Sowams also has led to speculation, usually downplayed by archaeologists and historians, that Massasoit, Alexander, or both may have been buried there. One of the graves unearthed was particularly rich in artifacts and contained a copper necklace thought to have been presented by Edward Winslow to Massasoit. Materials detailing the excavation of this grave are held by the Haffenreffer Museum.

Burr’s Hill was purchased by Warren in 1921 and made into a public park. Today, Burr’s Hill Park includes a baseball field, a playground, and parking for Warren residents interested in sunbathing along the river.

In July 1675, as Massachusetts forces were engaged in negotiations in Narragansett country and Plymouth’s troops were building a fort on the Mount Hope peninsula, Captain Matthew Fuller, Benjamin Church, and three dozen men crossed the Sakonnet river into Pocasset territory in present-day Tiverton, Rhode Island. There they hoped to meet with Weetamoe, and perhaps Awashonks to the south, to head off any agreement they might make to join Philip.

After a fruitless night spent attempting to trap unsuspecting Wampanoag, the band split into two groups of about twenty each under the commands of Fuller and Church. Fuller’s group quickly met up with Wampanoag warriors, retreated, and was ferried back to Aquidneck Island. Church’s troops marched south, probably along a Wampanoag trail east of Nannaquaket Pond where Main Road now runs.8 There they found tracks that turned inland.9 The small group followed these until they met with a rattlesnake (which were common in New England at the time), probably near Wildcat Rock.10 More afraid of snakes than Wampanoag, the men abandoned the tracks and returned to the main trail, heading south once again. Church later wrote, “Had they kept the track to the pine swamp, they had been certain of meeting Indians enough, but not so certain that any of them should have returned to give [an] account [of] how many.”11

After crossing onto Punkatees Neck (also called Pocasset Neck), probably west along the present-day Neck Road from Tiverton Four Corners,12 they proceeded south along the neck. Soon, they discovered more tracks heading up a hillside near an abandoned field of peas on land owned by John Almy. Shortly thereafter they spotted a pair of Wampanoag warriors, but when they attempted to follow, the English were caught in a thunderous volley “of fifty or sixty guns”13 from the hillside above. Church and his men, surprised and outgunned but unhurt, retreated “immediately into the pease field . . . But casting his eyes to the side of the hill above them, the hill seemed to move, being covered over with Indians, with their bright guns glittering in the sun, and running in a circumference with a design to surround them.”14 On the precise location of the peas field, James E. Holland, a lawyer whose longtime practice had its offices at the Old Grist Mill at Tiverton Four Corners, observed in a 1995 issue of Old Rhode Island that

the exact location of the peasefield on the Neck is the subject of speculation especially among those now living in its purported vicinity vying to attach some historical significance to their land holdings. However it appears from Church’s account that the field was somewhere on the hillside between the present Neck Road and the River, a short distance north of the road leading to Fogland Point.15

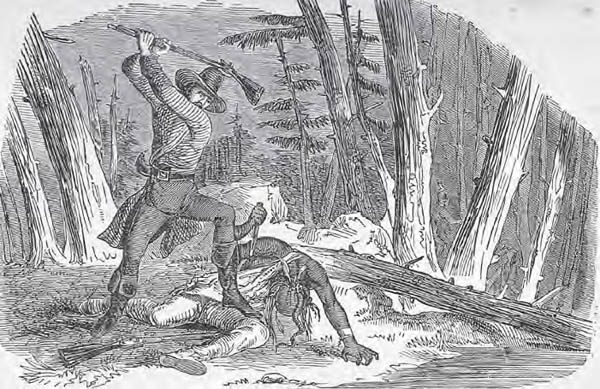

This nineteenth-century illustration re-creates Benjamin Church’s defense along the shore of Fogland Point in Tiverton, Rhode Island. (From Indian History for Young Folks, Francis S. Drake, 1885)

Church’s men retreated to the beach on the neck of land between Punkatees and Fogland Point, where they hastily constructed a barricade of rocks. Here they fought throughout the afternoon, holding off their attackers as a rescue attempt launched by men from present-day McCurry Point16 failed. Finally, Captain Roger Goulding, whose sloop was anchored at present-day Gould Island,17 spotted the battle and sailed south. Finding the sloop too large to beach, Goulding anchored so close that the ship’s “sails, colours and stern were full of bullet holes.”18 He then let a canoe over the side, allowing the tide to wash it onto the beach. There, two of Church’s men grabbed on and were pulled back to the sloop by rope. This rescue went on—two by two—until Church and his entire band were safely on board.

A check at day’s end revealed that two of Captain Fuller’s men had been wounded but—miraculously—not a single man under Church was hurt.

The precise location where Church and his troops mounted their defense was lost for some years by an error in a 1772 edition of Church’s History. When Church originally described the scene of the battle, he noted that “the Indians also possessed themselves of the ruins of a stone-house that over look’d them, and of the black rocks to the southward of them.”19 For some unknown reason, reference to these black rocks was omitted from the 1772 edition, and all subsequent editions. While editing an 1865 edition of Church’s History, Henry Martyn Dexter discovered the error, and armed with this new information, visited Punkatees Neck. Dexter wrote:

I found on the edge of the shore the remains of an outcropping ledge of soft black slaty rock, which differs so decidedly from any other rocks in the vicinity, and which—making allowance for the wear of the waves for near 200 years—answers so well to the demand of the text, as to incline me to the judgment that they may identify the spot. If this be so, the peasefield must have been on the western shore of Punkatees neck, a little north of the juncture of Fogland Point with the main promontory, and almost due east of the northern extremity of Fogland Point.20

Dexter also discovered the spring at which Church’s men quenched their thirst, “a spring stoned round like a well, and sending a tiny rivulet down to the sea, a few rods south of these remains of what were once ‘black rocks.’ ”21 In 1906, Ellis and Morris noted that “the spring at which Church records himself as quenching his thirst, has disappeared, and it is most probable the shore on which Church’s force actually stood has been encroached upon and swallowed up by the sea.”22

The Pocasset Swamp Fight was frustrating for the English, but the battle at Nipsachuck was disheartening. As Philip and Weetamoe crossed Seekonk Plain (the land around modern-day Route 1 in East Providence) they were pursued by men from Old Rehoboth, who chased them across the Pawtucket River into the town of Providence. From there the chase headed north, and at dawn on August 1, 1675, a battle was fought at a place called Nipsachuck, located in present-day Smithfield, Rhode Island. Philip’s men fought 130 English and fifty Mohegans, taking heavy losses in the exchange. Several of his chief captains were lost, and in all twenty-three Wampanoag died.23

By 9 AM the sides had disengaged, with Philip and his men fleeing into the nearby Nipsachuck Swamp. At 10 AM Captain Daniel Henchman arrived to take command with an additional sixty-eight English and seventeen friendly Indians, making the combined force 265 men. Philip cowered some three-quarters of a mile away, outnumbered three or four to one, low on ammunition, and prepared to surrender.24 Inexplicably, Henchman rested until the following day, allowing Philip to slip away into Nipmuc country and Weetamoe to advance south into the open arms of the Narragansett.

It is easy to criticize many of the actions of colonial military commanders in King Philip’s War. It is also generally unfair, since such criticism is the result of far greater information than the commanders had and is made from the security of three centuries’ distance. However, in the case of Henchman at Nipsachuck, both modern historians and Henchman’s contemporaries agree on his poor judgment. The captain was immediately and roundly criticized by his own troops anxious to pursue Philip. William Hubbard, whose work had to pass muster with Massachusetts Bay censors, noted: “But what the reason and why Philip was followed no further, it is better to suspend, than to critically enquire.”25 Later in the year the General Court reappointed Henchman to lead one hundred men gathered at Roxbury, but the men refused to serve under him. He was eventually assigned command of the garrison at Chelmsford and served ably in military activities throughout Nipmuc country. The episode at Nipsachuck, however, would dog Henchman throughout the remainder of his military service.

The precise location of the Battle of Nipsachuck is unknown. The Nipsachuck Swamp runs north to south across the border of North Smithfield and Smithfield, about ten miles north of Providence.26 Nipsachuck Hill, rising over five hundred feet, sits to the northeast of the swamp. Captain Nathaniel Thomas, who was present with Henchman, wrote an account of the battle on August 10, 1675. Thomas described a party of English and Mohegan scouting on the evening of July 31

who made some discovery of the enemy, by hearing them cut wood, and we left our horses there upon the plain, with some to keep them, and in the night marched on foot about 3 miles to an Indian field belonging to Philip’s men, called Nipsachuck, and at dawning of the day marched forward, about 40 rods, making a stand to consult in what form to surprise the enemy, without danger to one another, and in the interim, while it was so dark as we could not see a man 50 rods, within 30 rods of us, there came up towards us five Indians from Witamoes camp, (we supposed to fetch beans, &c. from the said field) perceiving nothing of us, at whom we were constrained to fire, slew two of them, the others fled, whereby Wittamas and Philip’s Camp were alarmed. Wittama’s camp then being within about an 100 rod of us, whom we had undoubtedly surprised, while they were most of them asleep and secure, had it not been for the said alarm; who immediately fled and dispersed, whom we pursued, slew some of them, but while we were in pursuit of them, Philip’s fighting men showed themselves upon a hill unto us, who were retreated from their camp near half a mile to fight us. Philip’s camp was pitched about 3 quarters of a mile beyond Witamas. Philip’s men upon our running towards them dispersed themselves for shelter in fighting, and so in like manner did we, the ground being a hilly plain, with some small swamps between us, as advantageous for us, as for them, where we fought until about 9 of the clock.27

Assuming that the hill upon which Philip’s men showed themselves was Nipsachuck Hill, Thomas’ description would place Weetamoe’s camp and the scene of the battle about one-quarter mile from the hill (i.e., Philip’s men camped three-quarters of a mile from Weetamoe, came one-half mile toward the English, and showed themselves upon a hill). The direction is less clear, though the English were pursuing Philip from the south and probably caught Weetamoe south or southeast of Nipsachuck Hill.

Henchman took up pursuit of Philip the following day, trailing him “till they had spent all their provision, and tired themselves, yet never coming within sight of Philip.”28

After a month of travel and three dramatic escapes from Mount Hope, Pocasset, and Nipsachuck, the sachem had successfully rendezvoused with his Nipmuc allies at Menameset in present-day New Braintree and Barre, Massachusetts.

The single bloodiest day of King Philip’s War was Sunday, December 19, 1675, when more than 1,150 English and Mohegan soldiers attacked the fortified camp of the Narragansett, sometimes called Canonchet’s Fort, located in the Great Swamp in present-day South Kingstown, Rhode Island. Tales of the attack would become the stuff of New England folklore, and the site of the fort itself a mystery that remains unsolved to this day.

The Narragansett campaign was set in motion on November 2 when the commissioners of the United Colonies assembled in Boston and accused the Narragansett, officially neutral to that point in the war, of being

deeply accessory in the present bloody outrages of the Barbarous Natives; That are in open hostilities with the English. This appearing by their harboring the actors thereof; Relieving and succoring their women and children and wounded men; and detaining them in their custody Notwithstanding a Covenant made by their Sachems to deliver them to the English; and as is credibly Reported they have killed and taken away many Cattle; from the English their Neighbors; and did for some days seize and keep under a strong Guard Mr. Smith’s house and family;29 and at the News of the sad and lamentable Mischief that the Indians did unto the English at or Near Hadley; did in a very Reproachful and blasphemous manor triumph and Rejoice thereat; The Commissioners doe agree and determine that besides the Number of soldiers formerly agreed upon to be Raised and to be in constant Readiness for the use of the Country; there shall be one thousand more Raised and furnished; with their armies and provisions of all sorts to be at one hour’s warning, for the public service the said Soldiers to be raised in like proportions in each Colony as the former were.30

The covenant referenced by the commissioners took the form of two agreements signed between the English and the Narragansett in July and October 1675. Both documents promised that the Narragansett would deliver to the English all Wampanoag in their midst, with the October agreement specifically obligating the Narragansett “at or before the 28th day of this Instant month of October to deliver . . . every one of the said Indians; whether belonging unto Philip; the Pocasset Squaw or the Saconet Indians Quabaug Hadley or any other Sachems; or people that have bin or are in hostility with the English.”31 The Narragansett were disdainful of both documents, which carried as little weight as Philip’s agreement at Taunton four years earlier.

Resistance by the Narragansett to English demands and the increasingly volatile state of affairs in Rhode Island was reported by Richard Smith Jr. in a series of letters to his friend, Governor John Winthrop Jr. of Connecticut. Smith operated the oldest and most active English trading post in Narragansett country and had as much at stake as any colonist in preserving peace with his Indian neighbors. In an August 5 letter, Smith noted that the Narragansett had brought in seven heads of the Wampanoag. More ominously, he added, “Many straggling Indians are abroad for mischief, some Nip Nap Indians joined with Philip, some Indians in Plymouth Patan are come into the English, about 120 in all as I here.”32 On September 3 he explained the source of the seven heads and his unease with the Narragansett, which was

that we are in jealousy whether the Narragansett will prove loyal to the English; if they pretend favor and hath lately brought in to me seven of the enemies heads, they being surprised by the Nipnaps first and delivered up to the Narragansett Sachem Conanicus. Here are very many inland Indians lately come in hither, and some of the enemy amongst them, which they, I judge, will not deliver. I believe yt Conanicus of him self & some others inclines to peace rather then war, but have many unruly men which cares not what becomes of them. These Indians hath killed several cattle very lately . . . It will be good to be moderate as regards the Narragansett at present I humbly conceive, for that a great body of people of them are here gathered together, may doe much mischief, and it if not brought into better decorum, here will be no living for English.33

Nine days later he sent another mixed message to Winthrop, who had now traveled to Boston to confer with commissioners of the United Colonies. Smith accused the Narragansett of hiding Philip’s people—“which these doe obscure all they can, and will not confess how many”34—but of also bringing in additional heads. Again Smith pled for moderation:

Cononocous hath brought in to me in all 14 heads, seven of which was lately, & some of them Phillips chief men. These being a great number it will be good to be moderate with them as it; for should we have war with them they would doe great damage . . . I should be sad if I could not be active in any respect whereby I might promote any thing that would tend to the peace & welfare of the Country.35

Finally, on October 27, just a day before the Narragansett deadline to deliver Wampanoag to the English, Smith wrote to Winthrop in Boston explaining that the Narragansett were “forward and willing to doe it, but say it is not feasible for them to doe at present, many of them being out a hunting, and their owne men being not so subordinate to their commands in respect of affinity, being allies to them, so that if by force they go about to seize them, many will escape.”36 Smith also reported that most of the English inhabitants in the area had fled, “the report common amongst Indians and English is at present of an army coming up. I request your favor to given me timely notice if any expedition be higherward.”37

This last point is remarkable in several respects. Smith and his fellow colonists—far from the flow of Boston politics—appeared to anticipate the Narragansett campaign several days before it was officially announced and nearly two months before the actual Great Swamp Fight. The same rumors had undoubtedly reached the Narragansett, who may have been well along in fortifying their Great Swamp village (about seventeen miles from Smith’s garrison), protecting their food stores, and readying their arms. If so, Canonchet would have had almost two full months to prepare his defensive strategy against the English prior to the December battle. However, if the Narragansett were steeling themselves for an English assault, Smith apparently did not learn of it and failed to report the existence of any kind of fort construction to the commissioners. The chance of hiding such a concentration of people and activity from English eyes might seem unlikely, until we recognize that neither Smith nor any of his countrymen ever discovered the Queen’s Fort (see below), a Narragansett installation located less than four miles from Smith’s trading post.

By the first week of December 1675, rumor became fact when troops from all over New England began to assemble. The Massachusetts militia, 527 men led by Major Samuel Appleton, gathered at Dedham, Massachusetts, on December 8. Many of the officers from earlier campaigns—Samuel Moseley, Benjamin Church, and Thomas Prentice, who headed seventy-five troopers—were pressed back into service. Plymouth assembled 159 men at Taunton under William Bradford. Major Robert Treat advanced 300 Connecticut soldiers, supplemented by 150 Mohegan, northward from New London, Connecticut. Governor Josiah Winslow was named general in chief and would soon assume command of the combined armies.

It seems unlikely that even now colonial officials suspected the existence of the Narragansett fort. Smith had still made no mention of such an installation. On November 19 the commissioners ordered that “provisions of all sorts and Ammunition shall be provided and sent to the place of their Rendezvous sufficient for two months,”38 a clear indication that they anticipated a campaign of skirmishes similar to what Major Samuel Appleton had conducted in the Connecticut River Valley the previous fall.

On November 2 when the commissioners had officially instructed the army to “compel . . . [the Narragansett] thereunto by the best means they may” to honor the terms of their agreements, colonial policy appeared somewhat equivocal in its goal for the Narragansett campaign. However, the commission to the commander in chief, written about the same time, was direct in its message:

You are accordingly to Instruct command & order all your inferior officers & soldiers in all respects with full power for the treating surprising fighting killing & effectual subduing & destroying of the Narrowganset Enemy & all their accomplices & Assistants as well the former open enemy or any others that you shall meet with in hostility against the English.39

On November 28, still several weeks before the army would march, the Council at Hartford reported their appointment of Major Treat to lead Connecticut forces, “desiring of them to engage the Pequot and Moheags to destroy the enemy, what they could.”40 With military leaders receiving orders like these, there could have been little doubt in any soldier’s mind as he assembled with his comrades in December that the army’s mission was to engage and destroy the Narragansett.

William Harris, a longtime foe of both Roger Williams and moderation with the Narragansett, perhaps best summed up the official colonial position regarding the campaign when he wrote to Sir Joseph Williamson:

The war was also just with the Narragansetts, many of whom were with Philip in the first fight about Mounthope, and on Philip’s flight thence were received back with a great woman of Philip’s party [probably Weetamoe] and her men; the Narragansetts, at the demand of the English, entered into articles to deliver them but did not, making large pretenses of peace so as to delay the war until after the harvest, and receiving rewards from the English for the heads of persons said to be of Philip’s party, but all in deceit, the heads being those of men killed by the English or of Narragansett deserters, or of certain of Philip’s men against whom they had a grudge . . . The Narragansetts had then many of Philip’s men whom they did not deliver up, and all about Hadley and Deerfield they aided Philip’s men against the English.41

With such strong sentiments commonly held against the Narragansett, the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth troops marched south. Along the way, General Winslow ordered his men to kill or capture any Narragansett encountered, attempting to ensure that word of the march would not reach the main body of Indians. Winslow sought especially the capture of Pumham, a Narragansett sachem whose territory included much of present-day Warwick, Rhode Island. Pumham had declared his independence from the Narragansett in 1644, allying himself with Massachusetts Bay officials who helped the sachem construct a fort on the eastern shore of Warwick Cove. The fort protected the entrance to the cove and was itself protected by an impenetrable marshy thicket42 to its rear. Pumham’s fort, occupied for a time by English soldiers, secured the interests of both Pumham and Massachusetts Bay.

The site of Pumham’s fort may still be viewed in Warwick on the north side of present-day Paine Street, at the bend in the road. The remains of the fort once formed a large and small oval in the earth but are now covered by brush and an accumulation of trash. The marshy thicket has been replaced by paved roads and graded home lots. The marker designating the site has been stolen, although its base is still standing.43

Despite his friendship with the English, Pumham allied himself with Philip once the war began and was now considered by the English to be a shrewd and dangerous opponent. Winslow’s attempt at his capture proved fruitless; Pumham was far too resourceful to be taken by surprise in his own fort. Winslow and his troops settled for the capture of thirty-five prisoners44 and continued their march.

Seven months later, on July 25, 1676, Pumham was attacked and killed at Dedham Woods.45 Hubbard described Pumham as

one of the stoutest and most valiant sachems that belonged to the Narragansett; whose courage and strength was so great, that after he had been mortally wounded in the fight, so as himself could not stand: yet catching hold of an English man that by accident came near him, had done him a mischief, if he had not been presently rescued by one of his fellows.46

Mather is more direct when he says that Pumham, mortally wounded, would still have killed an English soldier had the soldier not been rescued by his comrades.47

Richard Smith Jr.’s garrison and trading post at Wickford, Rhode Island, sometimes called Smith’s Castle, was chosen as the base of operations for the United Colonies’ combined troops. The location was ideal from the standpoint of being the center of political, social, and religious activity in the developing Narragansett area,48 having excellent access by water, and having a proprietor whose knowledge of the territory and enemy had been gathered through years of close contact with the Narragansett. In September 1684, nine years after the Great Swamp Fight, Richard Smith Jr. petitioned the commissioners of the United Colonies for compensation for the use of his trading post during the Narragansett campaign. His letter illustrates the activity that went on at his Wickford garrison in its role as headquarters for a poorly provisioned thousand-man army:

The humble petition of Richard Smith of Wickford, in the Narragansett, showeth, that your petitioner in the time of the late troubles and ware with the Indians here at Narragansett did suffer much in his estate by entertaining the many companies of soldiers, at his cost and charge, sent up by the Colonies; for which no recompense has yet been done to your petitioner.

1st. Major Savage and companies, with about 6 hundred, and Connecticut forces with him under command of Capt. Winthrop, they had horse shoes and nails to value 3lb 12sh, besides their entertainment 8 or 10 days, never pd. one farthing. After which, the entertainment of the whole army, myself and six of my servants being one service, one of which was slain at the swamp fight, had no allowance for our service. Also 26 head of cattle killed and eaten by the soldiers, with 100 goats at least, and at least 30 fat hogs; all the copper, brass and wooden vessels for the army used spoiled, stole and lost, to the value of near 100li sterling; great part of my post and rail fences being fetched and burnt for the soldiers; my oxen and cart and utensils being all lost, after the garrison went away; and lastly my housing burnt, being of great value. All which is too much for one particular man to bare; I having been to my utmost power ready to serve the Country always in what I could, nor even had anything allowed me for all above expressed, only for what the commissaries kept an account of, which was most salt provisions kept by me by order, for use of the army. Other men have had satisfaction in some measure; and when I last petitioned your Honors at Boston, I had a promise of consideration; wherefore this 2d time I doe request your Honors to take the premises into your judicious and wise consideration, to allow me in your wisdom what you shall think requisite, and your petitioner shall pray etc. and subscribe.49

Today, Smith’s Castle is located on Richard Smith Drive off Route 1 (Post Road) in North Kingstown and is maintained as a museum and gift shop by the Cocumscossoc Association. The present structure has gone through substantial alterations over the years. Smith’s original blockhouse, possibly set on the site of Roger Williams’ first trading post or on an adjoining tract of land,50 was burned to the ground by the Narragansett in 1676, as was every Rhode Island structure south of Warwick.51 In 1678 Smith’s son used some of the undamaged wood from the first house to build a three-room structure on the same site. Some of the 1678 building remains today, protected by an eighteenth-century expansion.52 On the north lawn of the house a burial ground holds the remains of forty English soldiers killed in the Great Swamp Fight. A tablet marks the spot of burial. No remains have been discovered at the site, though this may be due to the shallowness of the graves and rapid decomposition. A second graveyard at Burying Point, a short walk northwest of the house, is the final resting place of Richard Smith Sr.

Samuel Moseley’s troops, accompanied by Benjamin Church, had been sent ahead of the main army to secure Smith’s garrison and begin scouting activities. As the troops assembled at Wickford, a number of natives were captured, including a Narragansett named Peter. Peter immediately proved his worth to the English, alerting Winslow to two nearby Narragansett villages, which the English attacked and burned. However, Peter’s true value would come a few days later when he led the colonial army directly to the Narragansett’s fortified village hidden in the Great Swamp.

One of the deserted villages destroyed by the English was probably that of Queen Magnus, also called Quaiapen, Natantuck, the Saunk Squaw, and the “Old Queen” of the Narragansett. Not far from this village, in present-day Exeter, Rhode Island, was Quaiapen’s more famous “Queen’s Fort,” a natural stone fortification never discovered by the English during the war.

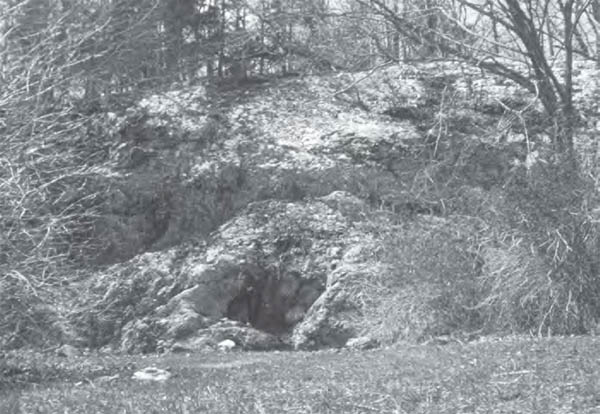

Signs of the Queen’s Fort still exist today, as does a longstanding mystery surrounding the site. The fort is located about three and one-half miles northwest of the Smith garrison, west of Route 2 on the south side of Stony Lane in Exeter. A fire trail about two hundred yards west of a barn and stone wall owned by Stonehaven Farm leads to the site, which is perhaps best described as a “geological trash pit” of huge glacial rocks. These rocks were thought to have been connected in a defensive pattern by the erection of stone walls, said to be the work of Stonewall John, a skilled Narragansett mason employed for a time by Richard Smith. The fort also appears to have two structures, perhaps bastions or flankers, on the northeast corner and west side.

The Narragansett sachem Pumham had such courage and strength, according to William Hubbard, that he nearly killed an English soldier despite being fatally wounded and unable to stand. (Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University)

According to the legend, Quaiapen occupied an underground chamber situated about one hundred feet outside the western perimeter of the fort. This chamber was described by Elisha R. Potter in his 1835 History of Narragansett, and again in detail in 1904 by Sidney S. Rider in The Lands of Rhode Island as They Were Known to Canounicus and Miantunnomu. Rider reported that the chamber

consists of an open space beneath an immense mass of boulder rocks; the tallest men can stand within it; the “floor” is fine white sand; the entrance is so hidden that six feet away it would never be suspected; the boulders piled about it represent a thickness of fifty or sixty feet.53

Despite these detailed descriptions and its appearance on several maps, the queen’s chamber can no longer be visited because—careful searches notwithstanding—its precise location is no longer known.

Quaiapen and her people occupied the fort after the Great Swamp Fight. In June 1676, sensing the end of the war, Quaiapen’s hungry band headed north, only to be attacked and massacred by forces under Connecticut’s Major John Talcott on July 2 in a cedar swamp at Nipsachuck. Both Quaiapen and Stonewall John lost their lives in the attack. Talcott wrote:

These may acquaint you that we made Nipsaichooke on ye first of July and seized 4 of ye enemy, and on the 2d instant being ye Sabbath in ye morning about sun an hour high made ye enemies place of residence, and assaulted them who presently in swamped them selves in a great spruce swamp, we girt the said swamp and with English and Indian soldiers: dressed it, and within 3 hours slew and took prisoners 171.54

Ellis and Morris called the spot of the massacre “Nacheck” and wrote that “this was on the south bank of the Pawtucket River, below Natick. The exact place of the massacre is not known. It was seven miles from Providence.”55 However, the correct location was determined by members of the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, who placed it “in Nipsachuck Swamp near Tarkin Station in North Smithfield.”56

The Narragansett fort located in the Great Swamp, probably built under Canonchet’s direction, was much different from the Queen’s Fort. It consisted of a complete village situated on four to five acres of highland, surrounded by swamp and enclosed by a wall of thick wooden stakes driven into the ground, earth, and brush. This fort contained some five hundred wigwams and was undoubtedly overcrowded due to the Narragansett policy of accepting any and all Wampanoag and Nipmuc refugees from the war.57 The English were not unaccustomed to seeing fort construction done by New England’s Native Americans; in fact, certain features of this fort strongly suggested the influence of European engineering.58 However, the Narragansett fort about to be assaulted was thought to be larger and more elaborate than anything in the colonists’ experience.59

The intent of both English and Narragansett became clear on December 15. Stonewall John appeared at Wickford allegedly to sue for peace.60 He was accompanied by a band of warriors hidden in the woods, suggesting that his real goal may have been to assess English military preparations. In any case, neither side proved flexible and Stonewall John was sent on his way. Shortly thereafter several English soldiers were attacked, including an assault on the hated Moseley, and the first English blood of the Narragansett campaign was spilled.

About this same time, nine miles south of Wickford, Jireh Bull’s stone garrison on Tower Hill in present-day Narragansett was attacked and destroyed by the Narragansett, who killed fourteen or fifteen English.61 While this assault is usually expressed as a tragedy for the English, Ebenezer Peirce wrote from the Narragansett perspective when he called it “a daring feat on the part of the Indians, with so large an [English] army not far distant and large reinforcements to that army daily and hourly expected.”62 What also made the feat daring was the apparent impregnability of the Bull garrison, described in a letter Captain Wait Winthrop wrote to his father, Governor John Winthrop Jr. of Connecticut, on July 9, 1675, as being a “convenient large stone house with a good stone wall yard before it which is a kind of small fortification to it.”63 Increase Mather would surmise that the structure was fortified well enough to withstand an outright attack, and must have been taken by stealth: “A body of the enemy did treacherously get into the house of Jerem. Bull (where was a garrison,) and slew about fourteen persons.”64

In 1918 the site of the garrison was positively identified through archaeological work undertaken by the Society of Colonial Wars of Rhode Island:

Part way up the eastern slope of Tower Hill on that portion of the “Bull-Dyer farm,” which is now owned by Mr. Samuel G. Peckham, here has been for many years a series of mounds, betrayed as stone heaps by the outcropping fragments, and marked, in part, as a rectangle by an old growth and buckthorns. The spot thus indicated has always been the traditional site of what is generally called Bull’s Garrison or Block House.65

Excavations at this site uncovered a wealth of artifacts and the existence of a stone house measuring thirty feet wide by forty feet long, with two fireplaces at its western end and the remains of a paved court on its eastern side. (A silver bodkin marked MB, perhaps for Mary Bull, was discovered at the site along with fragments of glass and tinned brass and iron spoons.) When the workers began digging westward in search of the wall Wait Winthrop had described, they found instead, about ten feet away, the outer wall of an even larger building. This second structure was divided into two rectangles by a heavy partition wall; the western rectangle—at twenty-seven feet wide and sixty-five feet long—was itself larger than the first building uncovered in the excavation. Remains of a heavy central chimney were discovered near the south wall and, on the eastern side of the chimney, a hearth made from blue slate. Among the objects uncovered in this second building were a pair of cock’s head hinges, a pair of H hinges, glass, part of a gun barrel, a flintlock, a dripping pan, and bits of various tools.66 About twenty feet south of this second structure workers discovered a third rectangular building that measured sixteen feet from north to south and showed evidence of a fireplace.

Historians believe that it was the second and largest of the structures that Wait Winthrop described and that fell to the Narragansett in December 1675. The first structure excavated was probably built by Jireh Bull or his son after King Philip’s War ended, perhaps after 1684. The small, southern structure is perhaps the oldest building on the property, though a fourth structure may yet be uncovered. All of the buildings on the property undoubtedly served as a ready supply of stones for the building of walls and foundations at nearby farms; “the outer wall of which Winthrop speaks was probably the first to go. Then the stones from the others were taken till the masonry was cut down to the level of the ground where it was soon covered by earth and grass.”67

In 1925 the Society of Colonial Wars published a further account of the objects discovered at the site. The account noted:

It is possible that in all there may have been three homes in this small clearing . . . and it is therefore impossible now to determine in which of the ruins some of the objects were discovered, as the laborers were not careful in reporting the exact locations of their finds . . . Some of the objects are undoubtedly from the house that was burned in 1675, others are certainly of a later period and from the house that Bull built after the war. Some of the objects may be still later, as the ruins of the houses may have been occasionally used as dumps for refuse . . . It is understood that practical jokers have recently buried skulls, bones and bottles containing messages, in the ruins in the hope of deceiving future excavators.68

Two years later, in 1927, the Society of Colonial Wars published A Plat of the Land of Capt. Henry Bull at Pettaquamscutt, Drawn by James Helme, Surveyor, January 8, 1729. This plat was prepared for the grandnephew of Jireh Bull by the grandson of Jireh’s northern neighbor, Rouse Helme, giving the document a strong basis in tradition69 and substantiating work done by archaeologists. The site of the Bull garrison, landlocked by private property, can be found today on the west side of Middle Bridge Road in Narragansett.70

Stonewall John’s visit, the destruction of Jireh Bull’s garrison, and the lack of adequate food supplies convinced Winslow that the war must be taken immediately to the Narragansett. On December 18, Massachusetts and Plymouth forces marched south to join Treat’s Connecticut troops; the combined army spent a wretched winter’s night camped around the darkened shell of the Bull garrison.71 At about 5 AM on the morning of December 19, with Peter in the lead, the colonial army trudged stiffly through the cold and snow:

What route they took to reach the fort—whether they went over Tower Hill, as some suppose, thence westerly by Dead Man’s Pool of the Saugatucket, over Kingston Hill and across the plains of Queen’s River; or by the Pequot Path southerly from Wickford, along the ridge of Tower Hill through Wakefield to what is now Sugar Loaf Hill, and so northerly again to the Swamp fort—perhaps never may be accurately known. Not one of the present roads was then in use except the Pequot path. But tradition has it that the Indian Peter, who was forced to be their guide under penalty of being hanged, was taken prisoner near the smoking ruins of Jireh Bull’s house on Tower Hill. If this may be accepted, the shortest path to the fort led across the Saugatucket, over Kingston Hill, and to it Canonchet’s hiding-place, full seventeen miles from Wickford.72

Some mystery remains in the distance and direction of this morning march. The Jireh Bull garrison is between seven and eight miles (on a straight line) from Canonchet’s fort. Joseph Dudley reported that the army’s march was “without intermission” and that the time of arrival at the Swamp was “about two of the clock afternoon.”73 (Captain James Oliver placed the arrival time “between 12 and 1.”)74 If the army were able to march straight to the fort, that would assume a speed of one mile per hour or less. Compare this to their retreat march when, burdened by the dark of night, frozen limbs, the walking wounded, and conveyance of the dead, the army would cover seventeen to eighteen miles between the fort and Smith’s Castle in ten hours between 4 PM and 2 AM, or nearly twice the speed of their first march. We are left to wonder what happened to so dramatically slow the march on the morning of December 19. Many historians exaggerate the mileage to rationalize the time, confusing the forward march with the retreat.75 Hubbard wrote that “they marched from the break of the next Day, December 19th, till one of the Clock in the Afternoon . . . thus having waded fourteen or fifteen Mile.”76 Thomas Hutchinson (perhaps repeating Hubbard) stated that “at the break of day, the 19th, they marched through the snow fourteen or fifteen miles, until one o’clock afternoon, when they came to the edge of the swamp where the enemy lay.”77 Ellis and Morris allowed that the fort was “sixteen miles to the west, by a circuitous route.”78 George Bodge solved the problem by assuming that the colonial troops marched north along the high ground to McSparren Hill and then turned west, crossing the Chippuxet River between Larking Pond and Thirty Acre Pond.79 It is only through this roundabout march via McSparren Hill that any distance close to the assumed fourteen to sixteen miles can be calculated, and even this assumes that the army would have marched almost as if it were lost, stumbling in a random pattern to the swamp. (Even if Peter were leading the troops so as to avoid a Narragansett ambush, the additional distance is still extraordinary.) It also assumes that Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth troops were required to march to the Jireh Bull garrison on the 18th—when word of its destruction had already reached them on December 16,80—only to retrace their steps the following morning. This would have added four difficult miles to their total march. It seems more probable that General Winslow chose the Bull garrison as a convenient rendezvous point with Connecticut troops and assumed that a direct westerly route to the fort could be taken from Pettaquamscutt. How or why the army would take as much as nine hours to reach a fort seven miles away remains a question.

Sometime after noon the lead colonial troops reached a “position on rising land some two miles beyond the present village of West Kingston.”81 There, at the edge of the Great Swamp, they traded fire with an advance party of Narragansett. It was then that the English discovered that the swamp, which was impassable most of the year, had frozen solid and would allow their advance to the fort.82 This factor, along with Peter’s knowledge of the fort’s weakness, would prove decisive for the English.

Benjamin Church, who would enter the fort only after the most intense fighting was over, reported that the English infiltrated the swamp “next the upland.”83 Writing in 1906, George Bodge interpreted this to mean “the rising land in front of the ‘Judge Marchant’ house,” which lay north of the supposed battlefield.84

The entrance to the fort used by the Narragansett consisted of a long tree spanning a “place of water.”85 This spot was well protected and would have been almost impossible for the English to breach. However, one small area remained unfinished along the fort’s lengthy stockade. This gap in the defense had been barricaded with a large tree trunk, about five feet off the ground. Most accounts record that Peter led the English directly to this spot, where the attack began. The fighting was vicious and went well at first for the Narragansett, who killed two English captains and drove the colonial force back into the swamp. Captain Moseley, near the front of the charge, drew particular interest from the Indians, who knew him well; he afterward told the general that he saw “50 aim at him.”86 The second wave ordered by Winslow breached the barricade, however, and the intense fighting moved in and around the tightly clustered wigwams. It was then that the order to set fire to the wigwams was given. As the afternoon wore on, many Narragansett men, women, and children were driven by flames and muskets to their deaths.

While Peter’s ability to lead the English directly to Canonchet’s Fort is unquestioned, the issue of the fort’s unfinished section deserves scrutiny. Peter was captured by Moseley’s men around December 16; this would have been the extent of preparations he would have witnessed at Canonchet’s fort. If a large segment of the fortifications were undone on the 16th, Peter could hardly have known the precise location of the last “chink” in Narragansett armor three days later when the English attacked. Conversely, if he knew about this specific spot of weakness—a single large tree trunk—on the 16th, the Narragansett would have had two or three days to repair this relatively minor deficiency before the assault occurred. A more logical conclusion would be that this spot was intentionally planned by the Narragansett, as was Peter’s capture, to ensure that the English would attack at a well-defended point and to discourage a search for other ways into the fort (which may have been plentiful, as they were intended as easy exits for Narragansett women and children). Perhaps this spot was intended to allow Narragansett reserves in if the English had attacked at another point in the palisade. Perhaps it served some other unknown military use. In any event, it presented a deadly passage for the English. Had the Narragansett not run out of gunpowder during the fight and instead pursued the decimated English troops, this contrived entrance might have been viewed not as a weakness but as a brilliant military tactic by Canonchet in a smashing Narragansett victory. The argument that it was the single unfinished and weakest point in the fortification either underestimates or misconstrues the Narragansett defensive strategy.

Other aspects of Canonchet’s leadership in the Great Swamp Fight are less brilliant. One wonders why the English were not harassed by the Narragansett at the Bull garrison or along the route of their march to the fort. The English had overextended their supply lines, were marching on unfamiliar terrain, had undoubtedly lost all element of surprise, and were attacking a fortified defensive position with numbers that would have been held vastly inadequate by modern military thinking. The Narragansett had two months to prepare their defenses and held almost every advantage in the Great Swamp Fight. Yet, by allowing the English to reach the swamp essentially unmolested, and then relying entirely upon the fort’s defenses, Canonchet committed perhaps the Indians’ single worst military blunder of the war. In addition, he failed to mount a flanking attack against the English position from outside the fort or even to send a small band to harass Winslow’s position, which most certainly would have distracted the English from the fort. He also failed to place an ambush along the retreat route of the English, a tactic employed brilliantly by the Nipmuc at other battles in King Philip’s War.87 Such tactics might have saved the lives of countless Narragansett women and children, who should have been able and encouraged to flee the fort before the worst of the fighting began and long before the decision by the English to set fire to the village was made. Indeed, stronger leadership could well have saved hundreds of lives and turned the English victory into a Narragansett rout, perhaps changing the course of the entire war.

About a month after the Great Swamp Fight the Narragansett were camped in the Misnock Swamp at present-day Coventry, Rhode Island, where they continued to be plagued by a shortage of gunpowder. A frustrated Canonchet is alleged to have said that “had he known they were no better furnished, he would have been elsewhere this winter.”88 One wonders if this wasn’t a more general self-assessment of his decision to defend the Great Swamp fort.

Joseph Dudley served as chaplain to the army (and later governor of Massachusetts) and provided one of the few firsthand accounts of the battle. In a letter written from Smith’s garrison to Governor Leverett on December 21, just two days after the fight, Dudley gave the following details:

Saturday [December 18] we marched towards Petaquamscot, through the snow, and in conjunction about midnight or later, we advanced; Capt. Mosely led the van, after him Massachusetts, and Plimouth and Connecticut in the rear; in tedious march in the snow, without intermission, brought us about two of the clock afternoon, to the entrance of the swamp, by the help of Indian Peter, who dealt faithfully with us; our men, with great courage, entered the swamp about twenty rods [about 110 yards]; within the cedar swamp we found some hundreds of wigwams, forted in with a breastwork and flankered, and many small blockhouses up and down, round about; they entertained us with a fierce fight, and many thousands shot, for about an hour, when our men valiantly scaled the fort, beat them thence, and from the blockhouses. In which action we lost Capt. Johnson, Capt. Danforth, and Capt. Gardiner, and their lieutenants disabled, and many other of our officers, insomuch that, by a fresh assault and recruit of powder from their store, the Indians fell on again, recarried and beat us out of the fort, but by the great resolution and courage of the General and Major, we reinforced, and very hardily entered the fort again, and fired the wigwams, with many living and dead persons in them, great piles of meat and heaps of corn, the ground not admitting burial of their store, were consumed.89

Benjamin Church says he entered the fort “that the English were now possessed of” with about thirty men, only to watch Captain Gardiner stumble toward him and fall, mortally wounded. Church also discovered and reported back to General Winslow that “the best and forwardest of his army, that hazarded their lives to enter the fort upon the muzzle of the enemy’s guns, were shot in their backs, and killed by them that lay behind.” He and his men then left the fort, found “a broad and bloody track where the enemy had fled with their wounded men,”90 and proceeded to skirmish with the retreating Narragansett. Church was wounded three times, once severely, and would retire soon after to Rhode Island to nurse his wounds during the winter months.

Indian losses in the Great Swamp Fight were thought to be significant but have never been accurately determined, in large part because contemporary English observers contradicted one another and had reason to inflate the figures, while later historians were careless in quoting these conflicting numbers. On December 21, 1675, just two days after the fight, the Reverend Joseph Dudley wrote that “we generally suppose the enemy lost at least two hundred men; Capt. Mosely counted in one corner of the fort sixty four men; Capt. Goram reckoned 150 at least.”91 Dudley was with General Winslow throughout the fight and spoke with many of the men in the days following the battle. He chose as his sources two soldiers, Captains Moseley and Goram, who were in the thick of the fight from the start. However, their assessment might have been influenced by several factors: Like all victors, the two men would have had reason to exaggerate the numbers of their enemy slain. In addition, both Moseley and Goram would have had to contend with the confusion and shock of the battle itself. Also, the English departed shortly after the fighting stopped and were never able to make a thorough accounting of casualties. However, less than a month later (January 14) Joshua Tefft92 gave credence to Goram and Dudley’s estimate of 150 to 200 Algonquian killed. Tefft, an Englishman, had been living in the fort with the Narragansett prior to the fight and fled with the sachems during the battle to a secure position away from the fort. After the English had retreated, the Narragansett returned to the fort to assess their losses. Tefft told Roger Williams that “they found 97 slain & 48 wounded.”93

James Quanpohit, a Christian Indian who spied for the English during the war, visited with Nipmuc and Narragansett warriors at their camps at Menameset not long after the Great Swamp Fight. Quanpohit probably would have been killed by the Narragansett (for his suspected friendship with the English) had not his longtime friend, Monoco, intervened; “he said he was glad to see me; I had been his friend many years, and had helped him kill Mohaugs; and said, nobody should meddle with me.”94 Despite being suspected as a spy, Quanpohit would hear and pass on to colonial authorities a wealth of accurate information concerning native plans to conduct the remainder of the war. In addition, Quanpohit would report that the Narragansett lost “but forty fighting men, and three hundred old men, women and children.”95 Among Tefft, Dudley, and the Narragansett themselves (through Quanpohit), the estimate of Indian dead ranged from 100 to 340 people.

Despite having listened to a month of wild speculation surrounding the fight, Captain James Oliver wrote on January 26 that the English had killed “300 fighting men.”96 This number of warriors killed is the upper limit of the estimates given by participants in the battle.

Nevertheless, contemporary reporters were either insistent on magnifying the English victory or simply willing believers of the many proud veterans returning from the fight. In 1676, merchant Nathaniel Saltonstall wrote to London that “our Men, as near as they can judge, may have killed about 600 Indian Men, besides Women and Children. Many more Indians were killed which we could have no account of, by reason that they would carry away as many dead Indians as they could.”97 Here Saltonstall introduces the idea, readily embraced by future historians, that whatever the number of Indian dead the English could confirm, there must be many more who were whisked away by the Narragansett in the heat of the battle. With this speculative start, another contemporary writer could report that “we have great reason to bless God we came off so well, our dead and wounded not a Mounting to above 220, and the enemies by their own Confession to no less than 600.”98

By the time Mather and Hubbard published their official accounts of the event, the numbers had grown again and the Puritan victory was even more glorious. Mather not only inflated the number but misquoted Joshua Tefft:

Concerning the number of Indians slain in this Battle, we are uncertain, only some Indians, which afterwards were taken prisoners (as also a wretched English man [Joshua Tefft] that apostatized to the Heathen, and fought with them against his own Country-men, but was at last taken and executed) confessed that the next day they found three hundred of their fighting men dead in this Fort, and that many men, women and children were burned in their Wigwams, but they neither knew, nor could they conjecture how many: it is supposed that not less then a thousand Indian Souls perished at that time. Ninigret whose men buried the slain, affirmeth that they found twenty & two Indian captains among the dead bodies.99

Hubbard, who was a more careful observer and accurate reporter than Mather, still chose his sources in a way that would glorify the English victory. Hubbard wrote:

What Numbers of the Enemy were slain is uncertain; it was confessed by one Potock a great Councilor amongst them, afterwards taken at Road-Island, and put to Death at Boston, that the Indians lost seven hundred fighting Men that Day, besides three hundred that died of their Wounds the most of them; the Number of old Men, Women and Children, that perished either by Fire, or that were starved with Hunger and Cold, None of them could tell.100

Benjamin Church is silent on the number of dead at the Great Swamp Fight. Hence, later historians who tended to rely on some combination of Church, Hubbard, and Mather for their information could easily establish that as many as seven hundred warriors perished in the Great Swamp Fight, and more than one thousand Indians in total lost their lives. Neither number squares with the few firsthand accounts remaining to us nor with the smaller numbers typical in New England colonial warfare.

It has generally been assumed that the English, by setting fire to the Narragansett wigwams, destroyed the better part of the Narragansett winter food stores. This rests on reports from Dudley, who noted that the fire consumed “great piles of meat and heaps of corn, the ground not admitting burial of the store”;101 from Captain James Oliver, who wrote that “we burnt above 500 houses, left but 9, burnt all their corn, that was in baskets, great store”;102 and from Church, who recorded that “the wigwams were musket proof; being all lined with baskets and tubs of grain and other provisions, sufficient to supply the whole army.”103 The extent of the damage to the Narragansett has been called into question by modern ethnohistorians, however. The Narragansett traditionally dried and stored their corn in the ground before an expected war,104 and there is no reason to expect that corn stored aboveground and burned at the Great Swamp Fight was more than a fraction of their total supply. The English did not dig for corn after the fight and, as far as we know, did not return to investigate the fort after the battle.105 We know from Joshua Tefft, however, that the Narragansett visited the fort a short time after the English departed; they may have uncovered and removed great stores of food.106

The same food and shelter destroyed by the English were also lost to the English, forcing them to return to Wickford in a march that began about 4 PM and did not end at Smith’s garrison until 2 AM the following morning. (One contemporary reported that “they marched above three miles from the fort by the light of the fires.”)107 General Winslow and a small group of men were separated and lost on the return march, traveling some thirty miles and not arriving at Smith’s garrison until 7 AM.

English losses at the Great Swamp Fight are well-known. Captain James Oliver reported that

we lost, that are now dead, about 68, and had 150 wounded, many of which are recovered. That long snowy cold night we had about 18 miles to our quarters, with about 210 dead and wounded. We left 8 dead in the fort. We had but 12 dead when we came from the swamp, besides the 8 we left. Many died by the way, and as soon as they were brought in, so that Dec. 20th were buried in a grave 34, next day 4, next day 2, and none since here. Eight died at Rhode Island, 1 at Petaquamscot, 2 lost in the woods and killed, Dec. 20, as we heard since, some say two more died.108

With some revision, modern historians have confirmed these numbers.109 Major Treat’s Connecticut soldiers took such severe losses that he deemed it necessary to return home immediately. Half of the combined officer corps had fallen, and four hundred soldiers who escaped wounds were so incapacitated by exposure and lack of proper care that Winslow’s army was incapable of continuing the winter campaign.110 Only the lack of gunpowder—“which Captain Oliver estimated at “but 10 pounds left”111—kept the Narragansett from pursuing the English and, despite their tactical errors during the battle, changing the outcome of the Great Swamp campaign completely.

With one notable exception, firsthand and other contemporary accounts are unusually silent on the role Connecticut’s Mohegan contingent played in the Great Swamp Fight. Numbering between 150 and 200 warriors, these allies of the English represented a fighting force equal in size to the Plymouth Colony regiment. If they had rushed the fort with the other Connecticut soldiers, they would have played a greater role in the battle than the Plymouth troops—who were held back as reserves by General Winslow—and taken even greater losses. Indeed, Connecticut historian Henry Trumbull believed the Mohegan suffered fifty-one dead and eighty-two wounded.112 The Mohegan under Oneko had already distinguished themselves in the war, having trapped and nearly annihilated Philip and his men at Nipsachuck in the previous summer campaign. Yet when Captain Oliver recounted the fight in January, he reported that the “Monhegins and Pequods proved very false, fired into the air, and sent word before they came they would so, but got much plunder, guns and kettles.”113 In this claim Oliver reflected not only the institutional bias of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth Colonies against the use of friendly Indians in warfare, but appeared to simply repeat the testimony of Joshua Tefft, who might have his own reasons for discounting Mohegan contributions to the fight. Tefft, soon to be executed as a traitor, told Roger Williams in January 1675/76 that “if the Monhiggins & Pequts had been true, they might have destroyed most of the Nihaggonsiks; but the Nahigonskis parleyed with them in the beginning of the fight, so that they promised to shoot high, which they did, & killed not one Nahigonsik man, except against their wills.”114 Old feuds between the Mohegan and Narragansett, the prior record of the Mohegan in King Philip’s War, their losses suffered at the Great Swamp Fight, and the assumed biases of Oliver and Tefft notwithstanding, the story that the Mohegan deceived the English at the Great Swamp Fight was picked up by Samuel Drake in the Old Indian Chronicle and has been repeated without further substantiation by historians throughout the years.

The Great Swamp Fight ensured that the roused Narragansett would now prosecute the war against the English with great vengeance. A series of peace talks were held throughout the end of December and on into early 1676, but it seems in retrospect that both sides were stalling for time to recoup and plan their next moves. It is also possible that the Narragansett were paying for their neutrality with the Nipmuc and Wampanoag. James Quanpohit reported that “the Narragansett sent up one English head to them by two of their men; and they shot at the Narragansett, told them they had been friends to the English, and that head was nothing. Afterwards they sent up two men more, with twelve scalps; they received them, and hung the scalps on trees.”115 The delaying tactics used by the Narragansett may well have been an indication that they were, at least temporarily, caught between sides of the conflict. The English themselves were trying to deal with desertions brought about by the harsh weather and poor care following the battle. Authorities in Massachusetts Bay were forced to pass a law making it illegal for a man “to conceal or hide himself or armes from the country service.”116 A new request for the raising of one thousand men went out to the colonies while Winslow tried desperately to prepare his remaining army for a new campaign. Only in late January did the situation brighten for colonial troops when fresh English and friendly Indian recruits arrived at Wickford.

For the last century the site of the Great Swamp Fight has been subject to great debate. Nineteenth-century antiquarians wrote with confidence about its precise location. The Memorial History of Boston, published in 1882, claimed that the fort was near “Kingston hill, by which the Stonington railroad closely passes; the only vestiges to be found to-day are here and there a grain of Indian corn burned black in the destruction.”117 In 1885, J. R. Cole noted that “the Great Swamp above referred to is situated on a farm now owned by John G. Clarke . . . Mr. Clarke, who has given the subject much consideration, has, he says, plowed up charred corn, the relics of the battle.”118 George Madison Bodge noted in 1886 that the scene of the battle was well identified:

It is situated in West Kingston, R.I., and belongs to the estate of the late J. G. Clark, whose residence was about one mile north-easterly from the old battlefield. Many relics of the battle are in possession of Mr. Clarke’s family. Saving changes incident upon the clearing and cultivation of contiguous land, the place could be easily identified as the battlefield, even if its location were not put beyond question by traditions and also by relics found from time to time upon the place. It is now, as then, an “island of four or five acres.” Surrounded by swampy land, overflowed except in the driest part of the year. The island was cleared and plowed about 1775, and at that time many bullets were found deeply bedded in the large trees; quantities of charred corn were plowed up in different places, and it is said that Dutch spoons and Indian arrowheads, etc. have been found there at different times.119

In 1906 Ellis and Morris located the fort at the same site as Bodge, on an island “between the Usquapaug River and Shickasheen Brook.”120

The site described by Ellis and Morris, by Bodge, and in the Memorial History of Boston represents the present-day location of the Great Swamp Fight Monument, placed in 1906 at a ceremony sponsored by the Societies of Colonial Wars of Rhode Island and Massachusetts. A roadside marker located one and one-third miles south of the intersection of Route 2 and Kingstown Road (Route 138) points to the location of the monument, which is found by walking or driving about one mile south from the marker along an unpaved road. The Great Swamp Fight Monument is made of solid granite, weighs eleven tons, and sits twenty-six feet high in the center of an upland “island.”121 Surrounding the shaft are four large boulders bearing the names of the three United Colonies and Rhode Island. The inscription at the base of the monument is badly damaged and, in any case, inaccurate when it suggests that the NARRAGANSETT INDIANS MADE THEIR LAST STAND in the Great Swamp Fight. The monument draws a large number of tourists and is an important site for descendants of both the English and Narragansett, who meet there annually to commemorate the battle.

Despite the certainty of nineteenth-century antiquarians, most modern historians and archaeologists disagree that the correct site of the Great Swamp Fight has been identified. Firsthand descriptions were vague and inconclusive. Benjamin Church said simply that the army marched “to a swamp which the Indians had fortified with a fort.”122 Another contemporary account noted that “our whole Army . . . went to seek out the enemy, whom we found (there then happening a great fall of Snow) securing themselves in a dismal swamp, so hard of access that there was but one way for entrance.”123 A third contemporary account described the following: “In the midst . . . [of the swamp] was a piece of firm land, of about three or four acres of ground, whereon the Indians had built a kind of fort, being palisado’d round, and within that a clay wall, as also felled down abundance of trees to lay quite round the said fort.”124 Joshua Tefft reported that once the battle began he “stayed 2 volleys of shot, & then they fled with his master, & passed through a plaine, & rested by the side of a spruce swamp.”125 Such descriptions are remarkable for the paucity of detail they leave for modern historians and archaeologists.

An eighteenth-century diary entry and sketch by the Reverend Ezra Stiles, president of Yale University, is the slim piece of evidence most often used to bridge the gap between firsthand accounts and the site of the twentieth-century monument. Stiles visited the Great Swamp on May 28, 1782, and wrote:

The swamp Islet is surrounded every way with a hideous Swamp 40 Rds to one mile wide, & inaccessible but at a SW Entrance & there a deep Brook or Rivulet must be passed. All the Narrag. Indian Tribe with the Indians of Mt. Haup or Bristol were assembled there in the Winter of 1675, when they were attacked by our Army of about a thousand men, who rushed over the narrow passage of Entrance & set fire to the Wigwams—a great Slaughter!

The burnt Corn remains to this day, & some of the Bones are yet above ground, as I saw at this time. The owner of the Land Mr. Clark is now clearing up the Land, has cut down the Timber & Brush, and will plow it up this Summer.126

Stiles also sketched and measured the area on which he believed the fort was located. His map shows a kidney-shaped area of upland some four acres in size consistent with firsthand accounts. Stiles also noted two Narragansett burying places and two oak trees, cut down the same year of his visit, 1782. One of the oaks was found to have a bullet lodged near its center, which was surrounded by one hundred rings (presumed to indicate the correct period between Stiles’ visit and the Great Swamp Fight).

Stiles’ account, so detailed in some respects, fails on three counts. First, we are unable to place his location precisely within the Great Swamp. Second, Joseph Granger has pointed out that “it is unlikely that such trees [as the two oaks] would have been left standing in a village moved specifically for firewood availability as much as for protection.”127 None of the firsthand accounts mention trees within the fort, which might have been used as defensive positions by the Narragansett, or as badly needed material for the palisade, and in any case, would have been remarkable landmarks in an otherwise cleared village site. The third weakness in Stiles’ description is what is left unsaid; the minister fails to mention the kind of substantial discovery of artifacts and “footprints” that would be left behind by a large, densely populated Narragansett village.

Since placement of the monument in 1906, historical and archaeological work has essentially confirmed skeptics’ beliefs that the fort is mismarked. In the 1930s and 1940s, the memorial site itself was pockmarked with random holes left by visitors, many of whom paid local owners twenty-five cents a day to dig for artifacts. By the mid-1940s one local resident digging at the memorial site found nothing but sand.128

A promising start in identifying the fort was made in 1959 when professional anthropologists from the University of Rhode Island, Columbia, and Yale excavated a site on the southern end of Great Neck, about two miles from the monument. (Great Neck is one of the pieces of high ground within the swamp that some think may have been the site of the fight.) A newspaper account reported that

in two weeks of painstaking digging and sifting, reaching about two feet under the surface of a rock shelter that served as an Indian home for centuries, the scientists have found nearly 2,000 pieces of bone, pottery, sea shells, ornaments and stones . . . Erwin H. Johnson, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Rhode Island . . . said some of the relics and artifacts “almost certainly” go back to the postglacial period . . . Professor Johnson cautiously avoided appearing too confident that the search would definitely establish the site of the Great Swamp Fight. “It will take more studying and we’ll have to do some digging at the place where the fight is supposed to have taken place” . . . Thomas J. Wright, chief of the Rhode Island division of fish and game and a student of Indian lore, suggested the site to Professor Johnson on the basis of his studies . . . He said that a number of persons have had doubts over the years that the Swamp Fight was fought where some historians say it was . . . Professor Johnson does not discount the fact that the rock shelter where he and his associates are digging might have served as an ideal fort. It stands on high ground, backed up by more rocks, and overlooking a valley.129

Sometime after this activity, Johnson wrote in the URI Alumni Bulletin:

Old writings specify an island as the site of the fort and a first trip over the swamp in a helicopter this fall showed an island now filled in on one side and a line of differentiation in the foliage which could indicate a ditch or fortification. This possible location is one and a half or two miles from the monument. Any disturbance of the earth such as an old foundation is much more readily visible from the air. We plan to take aerial photographs of the area, because these often show a perceptible change in the type and shade of foliage where there were habitations and burial areas even centuries ago. The next step will be to reach the spot on foot and then dig test trenches to look for evidence of palisades of the old fort and charcoal left from its burning.130

One of the students working with Johnson, Joseph Granger, conducted additional archaeological work around the site in 1960. Digging several test pits within 150 feet of the monument, Granger found the pits sterile and concluded that “no case may now be made for the Monument Site as the location of the Great Swamp Site of the Narragansett village of 1675.”131 Additional test area sites throughout the Great Swamp yielded intriguing but inconclusive evidence as to where the fort might have been located. Granger did conclude, however, that there were “traditional selective forces which governed [the fort’s] placement . . . [and that] topographic and environmental factors once isolated and combined with ethnohistoric data may show that, far from being a defensive reaction to Colonial encroachment, the 1675 winter village was merely a typical seasonal settlement in a consistently used refuge area.”132

Like Johnson and Granger, both professional and avocational archaeologists believe that there are pieces of high ground in the swamp away from the memorial site and not detailed on topographic maps that may indicate alternative sites for the fort.133 Many of these sites, suitable for traditional woodlands camps, are located on the northern perimeter of the swamp, around which bullets and burned corn have been found.134 It is also likely, according to historian William Simmons, that the Great Swamp has dried up since the seventeenth century so that “the fort site may be not in the present-day swamp but somewhere outside it, under plowed fields.”135

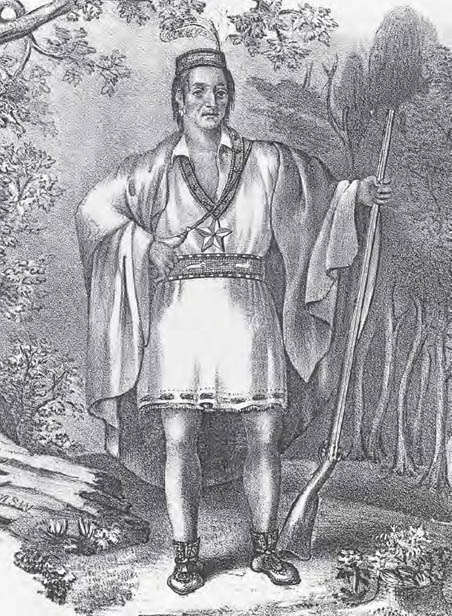

The Great Swamp Fight Memorial is designated by a state marker along South County Road in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. Many colonial Rhode Islanders, whose homes would later be destroyed by the Narragansett, might well have questioned the “decisive” nature of the Narragansett’s defeat. (Eric Schultz)