What is Creative Thinking?

Even though collaboration, teamwork and crowdsourcing have been on the rise, an individual’s thinking skills—specifically, his creative thinking skills—are arguably the most valuable skills one can own and market. “Individual creativity is absolutely critical … Without our individual employees, quite frankly, this agency doesn’t exist. It is really the combination of the brainpower of everybody that really makes this place tick,” says Roger Hurni, founder and chief creative officer of Off Madison Avenue in Phoenix. Hurni relates the brainpower of his employees to their ability to think creatively, as well as to the fact that they do not stop thinking after they leave work. “They’re the kind of people who are thinking about it, sort of letting ideas and issues percolate, even if they’re driving down the road, or they’re doing other kinds of things. So nobody here turns that off. [If] they have an idea at three o’clock in the morning, they’re going to get up and they’re going to get it figured out,” says Hurni. According to Margaret Johnson, executive creative director and partner at Goodby, Silverstein & Partners (GS&P) in San Francisco, the people who work at GS&P “are absolutely the most creative people in the industry.” Johnson points out that the employees are creative to begin with and that otherwise they would not end up at GS&P. This highlights the importance of harnessing one’s creativity to get jobs at certain agencies. As more companies in creative industries, specifically in marketing, advertising and communication are looking to hire creative problem solvers, more than just the so-called creative designers, art directors and writers need to demonstrate their creative thinking skills. Anyone interested in getting a job should be prepared to demonstrate some aspects of her creative skills.

According to Alexandra Bruell of Advertising Age, “creative executives are a hot commodity at a time when every marketer is looking for big ideas that can boost sales.” Individual agencies, as well as the advertising industry as a whole, are paying more money for people with creative skills. According to an Adage.com poll, creativity and creative thinking skills are sought to improve strategy and media and to generate big ideas. Evidence of this is found in the increased salary within the creative suite. For example, in 2013, more creative executives have seen a greater increase in salary than during the previous year. Thinking is a highly individualistic and complex activity that facilitates creativity and represents the process of being creative. As creative thinking can be learned and improved, it helps to understand some basic concepts.

American psychologists J.P. Guilford and E. Paul Torrance, among other researchers and creativity specialists, established a clear way to describe and assess thinking. Guilford developed a framework featuring two different modes of thinking: convergent thinking and divergent thinking. He was a strong proponent of the idea that creativity is inherent in all individuals.

According to Vincent Ryan Ruggiero, author of The Art of Thinking, the mind works predominantly in two ways: the production phase and the judgment phase. The production phase is responsible for the mind’s ability to produce a variety of possible solutions to problems or challenges and to look at problems from various perspectives. This phase also includes abilities associated with creative thinking and imagination, specifically one’s ability to apply divergent and convergent thinking. During the judgment phase a person examines and evaluates creative production and applies critical thinking. The judgment phase is also associated with the fact that the mind makes judgments. Ruggiero defines thinking as “any mental activity that helps formulate or solve a problem, make a decision or fulfill a desire to understand. It is a searching for answers, a reaching for meaning.” Human beings are all born with the ability to think and are trained in developing thinking skills further through education. During high school and college, we learn how to apply different kinds of thinking in subjects like mathematics, sciences, languages, literature, history and art. Many have been trained to develop specific thinking skills related to critical thinking, analytical thinking and deductive reasoning.

Creative thinking is also described as a mental process in which past experiences are combined and recombined, frequently with some distortion, in such a way that new patterns, new configurations and new arrangements are created. These are then applied to a given problem, ultimately creating solutions that can range from fairly common and seen before to more unusual, creative and original. Consequently this enables a person to come up with new and innovative approaches when solving a problem.

The two main kinds of thinking that facilitate creativity can be divided into conscious thinking, also called vertical thinking, and unconscious thinking. Conscious thinking is applied when one incorporates the information gained through the sensory system and consciously applies that knowledge to a certain situation. It can be a powerful way of thinking, since we can actively influence the direction we want to think or determine the perspective from which we look at specific problems. During conscious thinking we can play a more active role when making mental connections between two thoughts or ideas. In our minds we can draw from our knowledge, bringing together random thoughts from different disciplines and experiences where no obvious connection might exist.

Yet this conscious thinking happens at a slower rate than unconscious thinking does. Unconscious thinking represents an integral part of the creative process and typically happens at a faster rate than conscious thinking. It also occurs nonsequentially. When a mind is thinking unconsciously, it can go in numerous directions. However, this happens within a very short time frame, and you may not be aware of the connections your mind makes.

While forming the “structure of intellect model,” Guilford established the concept of convergent and divergent thinking. Convergent thinking assumes that the logical imperative is to go down a path in order to arrive at a specific solution that has previously been determined. Convergent thinking applies when the thinking process is focused on finding a single correct answer to a problem. Ideas are generated, weighed and discarded until the correct solution is found. For example, multiple-choice tests apply specific knowledge. During a test, your mind sifts through your knowledge, then decides if it matches a question and applies it accordingly. Convergent thinking describes a systematic approach to sifting through information and finding the most appropriate solution for a problem, challenge or task.

Alternatively divergent thinking, initially is not focused on arriving at a specific solution but is focused around trying to come up with as many possibilities as possible. Divergent thinking happens when ideas and thoughts are followed and explored in many directions. This type of thinking can be used to consciously increase the total number of possible solutions without being concerned about whether these solutions will ultimately solve the problem. This allows you to better push yourself to come up with as many different ideas and concepts as possible without expecting those ideas to relate to one another. Divergent thinking is a process that moves away from finding only one specific solution to a problem or answer to a challenge. Instead the mind tries to see as many different possibilities as one can imagine.

Divergent and Convergent Thinking10

While creative thinking has historically not been considered a strong component of the American education system, educators, psychologists and politicians in recent years have identified the need to place greater emphasis on the topic. Undergraduate students in American colleges and universities are already or will soon be educated in the areas of creative thinking. The Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU) developed a tool for Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE) and created a creative thinking value rubric to help educators teach creative thinking. This rubric helps to assess the learning outcome associated with specific skills like risk taking, problem solving, embracing contradictions and innovative thinking as well as connecting, synthesizing and transforming. According to AACU, “creative thinking is both the capacity to combine or synthesize existing ideas, images or expertise in original ways—it is the experience of thinking, reacting and working in an imaginative way that is characterized by a high degree of innovation, divergent thinking and risk taking.”11

E. Paul Torrance, the famous creativity researcher and creator of the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT), a standardized test that assesses our creative abilities and thinking skills, defined creativity as “a process of becoming sensitive to problems, deficiencies, gaps in knowledge, missing elements, disharmonies, and so on; identifying the difficulty; searching for solutions, making guesses, or formulating hypotheses about the deficiencies; testing and retesting these hypotheses and possibly modifying and retesting them; and finally communicating the results.”12 Influenced by Guilford, American psychologist and creativity researcher, Torrance decided to use four main components that he considered important to divergent thinking and creative thinking skills.

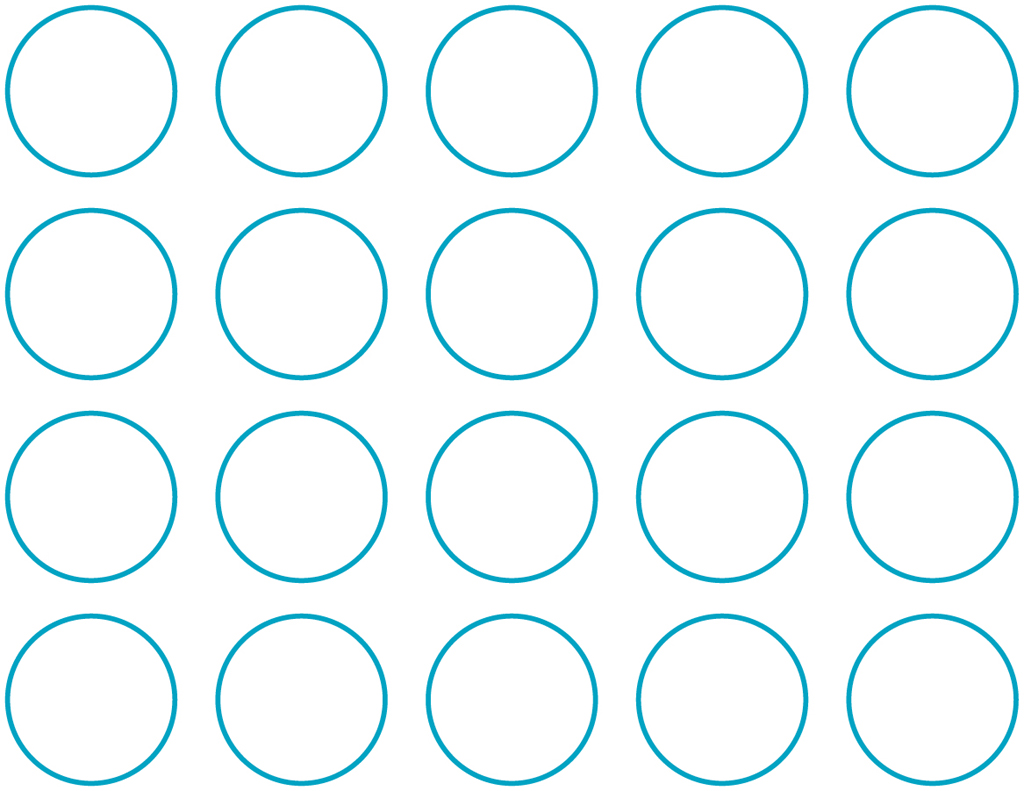

Fluency refers to the ability to produce a large number of ideas or alternative solutions when working on a problem. Two dimensions easily measure fluency: time and number of ideas. Testers can set an idea quota and measure how long it will take to come up with a certain number of ideas. Additionally they can define a time limit and measure the number of ideas developed during that period. Fluency represents the ability to access previous knowledge and make as many associations as possible related to the problem. In the case of the Twenty Circles exercise, the task consists of filling the circles with meaningful shapes. The faster you can complete the task, the more fluid your thinking skills are. During this exercise it is helpful to scan your knowledge/memory and remember anything you have seen or associate with a circle or round shape. Circles appear everywhere in the world. During the many circle exercises conducted over the years, professionals and students have typically drawn a manhole, a ball, a ring (e.g., wedding, engagement or diamond), an orange, a plate, a coin, an earth, a moon, a cup or symbols like yin and yang.

Flexibility refers to the production of many kinds of ideas—and the concept behind those ideas must be different from each other. Similarly to fluency, you tap into your memory and knowledge and sift through anything that connects (such as circular shapes and roundness for the circle exercise). Additionally, while coming up with many ideas, you also are aware that every idea you come up with is different from the other. During the many circles exercises conducted during creativity courses, students and practitioners often draw items of similar concepts, such as baseball, soccer ball, golf ball, basketball and beach ball or moon, faces with different facial expressions such as happy and sad during the first round. Yet, when drawing symbols of similar or same concepts, like different types of balls or round fruits, our thinking is limited and less flexible. The most flexible thinking can be demonstrated when drawing shapes that represent many different concepts and meanings. Within the context of the circle exercise, flexible thinking is expressed not only by how many different circles we are all familiar with but also by drawing objects that are not circular or round at first glance. For example, everyone is familiar with a pen or pencil, yet few look at a pen from the top or bottom perspective. Or see the holes in Swiss cheese. Or combine two circles to draw a bicycle or car. Or a pair of glasses. Or a pig’s snout. Compared to the more easily seen examples (such as an orange or moon), the pen, Swiss cheese, pair of glasses, bicycle and pig’s snout require the ability to switch thinking modes more quickly. This includes the ability to look at details while also being able to see the big picture. Roger Hurni highlights the importance of this ability in a business context: “We want people to look at our client’s problem and be able to solve them from a different perspective and not just rely on [the] tried-and-true or best practices kind of techniques.”

Elaboration is the ability to apply more details and enhance an idea. This includes adding several other ideas that might expand an existing idea or fine-tuning an idea and improving it by making it more beautiful or adding more detail. Elaboration also relates to the ability to see details that other people overlook, to add information and to look for a better way when others might stop. For example, I can think of an egg and see it not only as an oval shaped object but as a round object when looking at it from above. Then I can expand the idea of the egg and relate it to the circle exercise and come up with a hard boiled egg cut open and exposing the round egg yolk enclosed by the egg white. Depending on how I look at the egg its shape will differ. Elaborating further I can also see an egg sunny side up where the egg yolk takes up the shape of the circle and the egg white expands beyond the circle outline. Imagination comes into place and can push an idea further. Questions like What if we did this? or What if we did such and such? could expand an idea. “It’s not just about killing ideas, it’s about making the ones that exist better,” says Tim Leake, global creative innovation and partnership director at Hyper Island.

Originality relates to the ability to develop unique or unusual ideas, as well as putting things or situations in a new or unusual context.13 In a classroom setting, originality is usually typified by a single student developing a specific solution to a problem that no one is seemingly able to do. In a business setting, originality is a highly sought factor. “I think the qualities that really good creatives have, natural or taught, is a kind of natural inclination towards original thinking,” says Mark Hunter, former chief creative officer at Deutsch LA. He argues, “The really great creatives solve the problem in a different way, bring a very original solution to the table. And I think, in the same way, great creatives are probably the central component in making good work alongside a good brief and all those other things, but [the creatives themselves] are the dominant force … For me, I think originality is the dominant force.” Tom Moudry, president and chief creative officer at Martin Williams in Minneapolis is looking for interesting things that have not been seen before and for new ways of looking at something.

The increased focus on developing creative thinking skills during college represents an important step toward building valuable skills beyond a special degree in a core discipline. In addition to looking for industry-specific specialists, employers are looking for prospective employees with creative thinking and problem-solving skills. In creative industries, like architecture, performing arts, film, media, advertising, visual design and product design, individual thinking skills are considered even more important. According to Norm Shearer, chief creative officer at the agency Cactus Marketing Communications in Denver, the aim is to hire creative people, whether they are an assistant at the front desk, the CEO, an account person, or a media person. He believes that it is not just the creatives that are creative. “I think everyone has to be creative,” Shearer says. Lance Jensen, co-founder of the former agency Modernista and chief creative officer at Hill Holiday in Boston, says “In our agency, our value walks out the door every night. [It’s] all we have, other than some chairs, some Macs and a keg. So, if we don’t have good people, you don’t get good work.” According to Edward Boches, former chief creative and innovation officer at Mullen, the output of any company heavily relies on the individual part of each employee. “Even though we live in the ‘wisdom of the crowd,’ where crowdsourcing has become more and more important, it is the individual ability to create, design, invent, inspire and think that makes a company successful,” says Boches.

David Droga, founder and chief creative officer at Droga5 says, “I try to hire as many inspiring, interesting, authentic creative people as possible and that manifests itself in many different ways. I’m not looking for one type of creative person or one type of creative thinker. I look at problem solvers. I look for people with disparate backgrounds and give them the canvas and the freedom to express themselves.”

Doug Spong, president at Carmichael Lynch Spong in Minneapolis, believes that “Highly creative people have an enormous attention to detail. I don’t mean typos and grammar. What I am talking about is they tend to notice things in personalities, characteristics and behaviors of the people around them. They tend to notice very minute details.”

Understanding how people think and how one can improve thinking skills provides you the opportunity to practice your thinking on a regular basis and improve your divergent and convergent thinking skills. Since many people learn from practical experiences as well as theoretical cases, this book includes several examples of how young professionals, who have studied creativity during a college course, have improved their thinking.

Former student Alyse Dunn describes her situation. “I entered my Creative Thinking course at Emerson [College, in Boston] as any ideal student would. I sat there thinking, ‘What will this class really teach me? I am already creative. What more could I learn?’ I quickly realized that there was a lot to learn and that the creativity that was so inherent had been slowly wilting away, and I hadn’t even noticed. As we were given creative thinking tasks, I found it challenging to think quickly and really pull unique thoughts. My mind felt rusty, which it never had before. I didn’t like the feeling, but it also wakened me to a stark reality: If creativity is inherent, then how can it be slipping away? I took the rustiness as a sign that I needed to challenge my mind more. I read each book hungrily in order to shake my mind of the proverbial cobwebs. I pushed myself to actively engage in the classroom activities and not default to the easy answer. It was a challenge, which was new to me. I wasn’t used to working so hard at being creative, but I am so thankful that I did. I could see the change in the way I thought and looked at problems. I could think faster, look at problems from many different angles and truly arrive at solutions that I would not have been able to originally. I really enjoyed this change. I began to pursue creative avenues in my everyday life.

In the past, I had always been actively involved in anything creative, but when I left college and moved, I lost that part of myself. I never realized how much I missed it until I began retraining my mind. I began taking card making classes and crepe making classes. I began dancing again and exploring different museums and historical landmarks. I read books that I enjoyed and started writing creatively again. I took back that part of my life. My creative course taught me how to hold on to my creativity and how to hone my creative skills. Whenever I am feeling mundane, I do something that sparks creativity. It is something I truly enjoy, and it is eye-opening. You can really see the world differently and that has translated well into my career.”

The way the human brain works has not changed much over time. Fortunately technological advances in medicine, psychology and neurosciences have brought new information to light, allowing humans to better understand what is going on in our brains when creativity is at work. This new scientific insight might not make us better or more creative thinkers. However, new studies may help us understand what happens when we practice our thinking and further develop our creative skills.

You probably have heard that an individual’s thinking falls into two categories: left-brained or right-brained. According to this theory, each hemisphere controls different types of thinking. Left-brained people are said to be more logical, analytical and objective. Some of the abilities that are often associated with this side of the brain are logic, critical thinking, numbers, reasoning and language. Right-brained people are said to be creative and expressive. They are more intuitive, objective and thoughtful. Some abilities that are typically associated with this side of the brain are facial recognition, emotional expression, emotional reading, music, color, images, intuition and greater creative ability.

This theory grew out of work that was conducted by Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Roger W. Sperry. While working with patients suffering from epilepsy, Sperry discovered that by cutting the corpus callosum—the structure that connects the two hemispheres of the brain—the number of seizures were reduced and, in some cases, eliminated. However, this was not the only thing that occurred when this communication pathway was cut. Some split-brained patients that were unable to name objects that were processed by the right side of the brain but were able to name objects that were processed by the left side of the brain. With this finding, Sperry concluded that the left side of the brain controls language. Through extensive research, he believed that the two sides of the brain acted independently and had different processing styles. This eventually led to the left-brain, right-brain theory that is widely referenced today.

According to Rex E. Jung, the concept of left-brain and right-brain thinking and the distinct brain activities associated is part of “folk psychologies.” The concept that creativity is related to stronger right-brain activities has been promoted by popular media rather than supported scientifically. More recent studies have shown that in healthy individuals, these two sides of the brain are very much connected and have evolved to operate together in most everything a person does. In his own neuroscientific studies, Jung and his colleagues discovered that creativity takes more than just the right part of the brain. “If you didn’t have your left hemisphere, I guarantee you wouldn’t be creative,” Jung claims.

Although there are some tasks that the two hemispheres tackle independently, the integration of the two sides yields some of the most uniquely human characteristics. For example, when humans make mistakes, the realization and ability to correct a mistake is a result of both the left and right hemispheres working together. Individuals with damage to their corpus callosum have a more difficult time correcting their errors than people with healthy brains. Both hemispheres must work together to solve these problems. While there are certain tasks that occur primarily on one side of the brain, in certain circumstances, it is possible for the other side to take control of the process. For example, if someone experiences damage to his Broca’s area, a region located on the left side of the brain linked to speech production, there is an increased amount of activity in the right inferior frontal gyrus on the opposite side. This demonstrates that our brains, even as adults, have enough plasticity to adapt to change and damage.

You may think that your strengths are more left-brained or more right-brained in nature. However, the truth is that you can train your brain to think with both hemispheres. In fact, creativity flourishes the most when you are able to integrate both sides of the brain. You may think that your brain does not have the capability of being creative, but this simply is not true. Anyone can train her brain to be creative. It just takes practice.

The brain is an organ that can evolve. Much like regular exercise can help develop and strengthen muscles, the brain can be trained in a similar manner. The more exercise you do to engage your brain creatively, the more creative your brain will become. However, just like with physical exercise, you must train it regularly not intermittently. Many people feel like they are not creative because they are not actively engaging their brain in activities that trigger creation. Rather, many of the activities that we do on a day-to-day basis are training the brain to be passive not active. For example, many people spend hours watching television or browsing the Internet. These activities do not actively engage the brain in activities that train it to create. Furthermore, not many of us permit ourselves to do nothing—allowing our minds just wander and daydream. Think about your typical day; how much of that time is spent on passive activities rather than active ones?

The brain wants to be as efficient as possible and is always looking for the easy way out. This means that it seeks straightforward, familiar answers that are based on past experiences. This is why it may be difficult at first to break these habits and to force the brain to move from old thinking patterns to new ideas generated instinctively and on command. Neuroscientists once believed that the brain was fully developed by early adulthood and that there was nothing to be done after a certain time in a person’s life to change its chemistry. The fact that your brain can only be changed and developed during your formative years, in your childhood and adolescence, has been widely accepted. However, this belief has been overturned in recent years. Studies have demonstrated that the brain can, in fact, be changed and developed throughout your life by engaging it in various activities. Our brain is much more flexible than we think! In fact, the brain is neuroplastic, which means that it can learn new ways of thinking and create new neural connections. This can be done well into old age, which means that you can start changing your brain at anytime. It just takes practice and dedication.

In recent years several new methods have been built to aid in training our brains and strengthening our thinking muscle. Nintendo adopted brainteaser games for their Game Boy and numerous magazines publish puzzles and brain exercises. For example, the leading newspaper in Germany, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung,14 devotes a special section to brain training. And there are plenty of web-based services that provide exercises. These activities are all built on new findings in neuroscience that claim the human brain is not merely a preformatted computer with limited computing power but an apparatus that is flexible and can be trained.

Two brain researchers offer additional insight on how our brain works. The first, Joydeep Bhattacharya, a psychologist at Goldsmiths, University of London, found some interesting results when researching the influence of alpha waves. Specifically he discovered why it is so important to rely on taking showers, taking walks on the beach or doing something completely unrelated to the problem you are working on. These activities allow the brain to defocus. Our conscious and unconscious minds appear to be playing an important game of tennis, firing neurons back and forth along the alpha waves at high speeds and in increasing quantity—until the conscious mind reaches game point. According to Bhattacharya, the alpha waves stem from the right hemisphere.

The second brain researcher, Mark Beeman, a psychologist from the University of Chicago, also gained some new insight when looking at the neural source of insight. He gave a group of individuals specific brainteasers and observed how they solved them. Beeman found a strong connection between left-brain thought process and right-brain thought process. When we are given problems to solve, we apply knowledge that we have gained over time and try to solve those problems consciously through analytical thinking. Yet with many problems, we require new insight and perspective in order to solve a problem creatively. Rather than rely exclusively on associations we are familiar with, we need to shift our perspective. According to Beeman, unexpected associations occur when we step away from the given problem. He considers the “stepping away” a mental shift. By removing our focus from the problem, we can allow our brains to make connections that we are not consciously aware of. This shift can give us the insight and new perspective to solve what seems impossible and to see new connections.

In his article “Neuroscience Sheds New Light on Creativity,” Gregory Berns discusses how MRIs have shed light on how people develop new ideas. Berns argues that there are certain people, like Walt Disney and Steve Jobs, who belong to a certain class of people he calls Iconoclasts. In simple terms, they have the ability to see things differently. Some of these Iconoclasts are born this way. However, those of us not naturally blessed with these abilities can learn from Iconoclasts. According to Berns, “We all can learn how to see things not for what they are, but for what they might be.” The brain uses the same neural circuits for perception and imagination. “Imagination is like running perception in reverse,” says Berns. Many people have a hard time thinking of truly original ideas, which is in large part due to the way in which the brain interprets signals from the eyes. Your brain explains ambiguous visual signals by basing it on past experiences and things that it has been exposed to in the past. “Experience modifies the connections between neurons so that they become more efficient at processing information,” claims Berns. When you are exposed to something for the very first time, your brain uses an entire network of neurons to interpret it. However, by the time you are exposed to that same thing, say a sixth time, a much smaller number of neurons are at work because your brain has become much more efficient at interpreting this stimulus. Therefore, if people have been exposed to something multiple times and are asked to describe it, they are much less likely to use their imagination. But if they are asked to describe something less familiar to them, they provide more original and novel explanations. This is because they have fewer past experiences to rely on. Therefore, Berns claims that in order to think more creatively, a person needs to develop “new neural pathways and break out of the cycle of experience-dependent categorization.” If the brain has a hard time predicting what is to come next, the individual is more likely to use her imagination and think more creatively. This research is encouraging as it demonstrates that anyone can trigger novel thinking by exposing themselves to new environments and experiences. The more radical the change, the more likely it is that a person will have novel insights. Berns believes that “the surest way to provoke the imagination [is] to seek out environments you have no experience with.”

Anyone can be a creative type. It is just a matter of getting your brain to think in new ways and exposing yourself to new experiences and situations. A big aspect of creativity is allowing your brain to make associations and connections in places that you never thought possible. The likelihood that you will make unique connections is increased if you have more diverse information stored in your brain. Steve Jobs said that the best inventors are those people that seek out “diverse experiences.” This could mean a number of things. For example, you could take up something completely unknown to you, like playing the banjo. Or it could mean interacting with people from a different discipline than you and gleaning information from them to use in your own line of work.

Many companies are beginning to realize how important it is for people to be exposed to diverse experiences. The belief is that these activities will translate to better overall work for the company. In our interviews with the creative directors of various advertising agencies, many emphasized the importance of having interests outside of work. Marshall Ross of Cramer Krasselt says, “I think the people who are good, or who are successful, within creative organizations are people who are learning constantly from lots of different resources. They learn from their friends; they learn from their peers.” David Droga of Droga5 in New York engages in many activities that lie outside the realm of advertising. “I like being open to the world and seeing [things] because it sometimes can inspire in the most unlikely places. And I would say the majority of the work that I’ve done or the work that other people have done that I love, comes from something that is back to real life.” Of his employees, Droga believes that “they are more interesting people and more interesting creative thinkers if they have a real life out there and interests far beyond [the office]. So we certainly promote and celebrate any other interests, whether they are aligned with our business or not.”

R/GA, the digital agency responsible for Nike+ and many other innovative technology-based platforms, campaigns and products, fully understands the power and special interests of their employees, knowing that many of those interests lie outside the core business. Former student Sara Wynkoop’s research on R/GA’s culture (see her creativity essay at www.breakthroughthinkingguide.com) points out that the agency lets its employees explore activities like knitting, sketching, painting or creative writing through various employee special interest clubs. These activities provide great opportunities to defocus from daily problems and they expose the brain to activities in completely different fields and topics, sparking new insight.

Children arrive at original ideas more often because their thoughts are less inhibiting, allowing their brains to wander. They do not have a fear of failure that often paralyzes and inhibits an adult’s thinking. As children, humans are equipped with the ability to dream and be imaginative. They are less experienced and are still attempting to make sense of the world around them. Therefore, they have a greater propensity to imagine things. I invite you to take a brief moment and remember your own childhood or think of children that you know. Try to recall when you have asked your parents or relatives any “What If?” questions. In my experience, my youngest daughter, during her elementary school years, frequently asked questions like, “What if we lived for one day in a house that is upside down?” Or “What if I could fly like a balloon to the moon and touch it and my hair is so long that you can hold on to me?”

An excellent way to expose yourself to new experiences is the “Artist Date,” an exercise developed by Julia Cameron, which she describes in her book The Artist’s Way. I use this exercise in my course on a weekly basis and find that my students have explored new topics and areas, and gained new experiences. One student, who is not from Boston, believed that Bostonians seem to be rather cold and unapproachable. She realized that this was quite judgmental and began approaching a stranger once a week. Whether it was during a walk in the park or on the subway, she introduced herself and started conversations that allowed her to see people and the world around her through a new lens. Emboldened by her new insight, the student decided to take the bus, which she had never done before, and experienced new neighborhoods and areas in the city.

You can engage in simple things on a regular basis in order to boost your own creativity. It could be taking a new street to walk to your house or trying a new dish at your favorite restaurant.

Determine how you could complete the following sequence:

How would you place the remaining letters of the alphabet above and below the line to make some kind of sense?

The alphabet exercise illustrates how we can come up with different options to answer a problem that can be explained with more than one solution.

Exercises like the above allow us to use our imagination and apply our “divergent thinking” skills. Based on how we interpret the pattern of the letters we see, we can come up with multiple new ways to complete the sequence by using every letter of the alphabet.

Once we have come up with various ideas and options to complete the sequence we then have to ask ourselves if our solutions make sense and if our newly created patterns appear to fit the task.

Credited to Adams, James L. (1986), The Care and Feeding of Ideas: A Guide to Encouraging Creativity. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Credited to Wujec, Tom (1995), Five Star Mind, Games & Puzzles to Stimulate Your Creativity & Imagination, Doubleday, New York, and Evans, James R. (1991), Creative Thinking – In the decision and management sciences, South-Western.

Add drawings to all the circles to turn them into recognizable pictures. For example, you could draw a peace sign, a face, an eyeball, a wheel. Complete twenty different pictures. The circle exercise provides an excellent framework to illustrate the key concepts Torrance has developed.

Adapted from Wujec, Tom (1995), Five Star Mind, Games & Puzzles to Stimulate Your Creativity & Imagination, Doubleday, New York.

Now that you understand the different ways that we solve problems, use your sketchbook to identify three activities or recent experiences in which you have used one of the two different methods of creative thinking. 1. Convergent Thinking: the gas tank was on empty, so I went to the gas station and filled up the car. 2. Divergent Thinking: What can I do with a shoe?

Adapted from RSA Animate - Changing Education Paradigms, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U

Here is an interesting exercise that illustrates our minds at work: A man has married twenty women in a small town. All of the women are still alive and none of them are divorced. The man has broken no laws. Who is the man?

This exercise appears in numerous sources: The Malleability of Implicit Beliefs of Creativity and Creative Production, page 81, 2008, by Matthew C. Makel; Imagine: How Creativity Works, by Jonah Lehrer, 2012; and at www.indiana.edu/~bobweb/Handout/insightproblems.doc by Curtis J. Bonk.

Add drawings to all the circles to turn them into recognizable pictures. Since you have completed the first set of twenty pictures previously you can start all over again by drawing twenty completely new pictures. Try completing several sets of 20 circles and come up with a total of 150 pictures.

Adapted from Wujec, Tom (1995), Five Star Mind, Games & Puzzles to Stimulate Your Creativity & Imagination, Doubleday, New York.