During the interviews with various creative executives, the dimension of philosophy emerged in addition to the 4Ps: place, person, process and product. A clear overarching agency philosophy can influence the climate of an organization and, when paired with a focus on the creative product, can define a creative organization internally and externally, helping it to stand out among the competition, and provide an organization with its intrinsic motivation.

Across the board, I noticed that each one of the agencies that I visited had something special and unique beating in the hearts of those interviewed and their employees. An invisible force represented a mix of belonging, optimism and a can-do attitude. Among the employees and throughout the agencies, I detected an attitude of “There is nothing that can’t be solved!” It was a pledge that seemed cult-like or emblematic of elite military groups such as the Navy SEALs. Everyone I encountered seemed excited and motivated to be part of his or her respective agency. Motivation is something all individuals possess and is usually expressed as a driving force influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Based on my interviews, I believe that an organization as a whole can have intrinsic motivation as well, and that it is manifested as the agency philosophy.

The pirate culture at TBWA\Chiat\Day is apparent in many different ways.

All of the creative executives describe their respective company culture as one that places a strong emphasis on creativity. This emphasis often is reflected physically in the spaces in which employees work fully engaged and collaboratively in open environments. Beyond this, many of the executives mentioned an aspect that I would call an overarching philosophy or ideology. The agency philosophy influences the culture and represents the organizations’ intrinsic motivation to be the best within their domain of expertise. Often the company’s founders or leaders’ commitment to creative excellence represents that intrinsic aspect of motivation that is seen on an individual and personal level.

Rich Silverstein and Margaret Johnson, executive creative directors and partners at Goodby Silverstein & Partners, say that “creativity is everything” and that it represents the core of their agency. As Silverstein says, “Creativity to our agency is [like] air or water. You die without creativity. It is why we’re here. It is what we should be doing.” Through creativity, Goodby Silverstein & Partners has developed a strong new philosophy to “make stuff people care about.” The goal is to elevate their work to a place beyond advertising and to take on a bigger role in people’s lives. Johnson said that all of the work that they produce at Goodby Silverstein & Partners is constantly put through a filter of questions such as “Who cares about this?” “Why is this a creative idea?” and “Is this going to make a difference?” If the answer to any of these questions is no, the team goes in a different direction. In this way, an overarching philosophy helps ensure that everyone in the organization is moving in the same direction. Says Johnson, “it helps when everybody has a north star, and we are all working towards the same thing.”

TBWA\Chiat\Day uses the philosophy of “Disruption” and “Media Arts.” According to TBWA\Chiat\Day, disruption represents “the art of challenging conventional wisdom and overturning assumptions that get in the way of imagining new possibilities and visionary ideas,” and is a concept that can be applied to many aspects of business. Combined with TBWA\Chiat\Day’s culture of piracy, the leaders are taking creativity one step further and are constantly pushing themselves to deliver more than what is expected of them.

David Droga of Droga5 produces great creative results by bringing together the best minds in planning and strategy, and mixing them with the best creative skills in storytelling, production art direction, copywriting and digital software development. Droga says that his overarching philosophy is “to build the most influential creative business in the world.” He acknowledges that his philosophy is ambitious and “ridiculously a stretch,” especially when he wants to achieve this within an entire industry.

Droga is aware that in order to succeed, he has to overcome several challenges. “We have to be successful for our clients,” he says. “We have to contribute to society in a positive way; we have to rub up against other industries; we have to influence pop culture; we have to bring in the best new talent; we have to elevate our industry. I want to do great things with that, and as I said, that’s our goal, we have to build the brands of the twenty-first century, but at the same time, it’s creativity with purpose.”

For Droga, creativity is the fuel and the foundation of his agency. “It’s not biased toward the creative department. We are a creative company so we have great thinkers across many functions. While we’re a celebrated creative agency, our special secret source in the agency is our strategic thinking.” Droga considers himself lucky to be living in an era where “we can do great things with our imagination” and where communication is the newest and most powerful instrument needed in order to make a positive impact on the world. As he explains, “Creativity is no longer a sort of cute-little-nice-thing to have. It plays a massive role in society, and I’m glad that we’re part of it. I’m also glad that we’re in a time now where advertising isn’t this one little pigeonholed thing where it’s just about selling soap powder on TV and print ads. There’s nothing wrong with those things, but we can do so much more than that. We can help raise awareness of prices or raise money or contribute to pop culture or build industry—save industry. We’re not going to cure cancer but maybe we can help the doctor who is. And I feel like we want to touch and influence and make better every day. Everybody, communication and messaging and education, play a part in all fabrics of life, and that’s not to say that all advertising is good advertising. I get it, I know. I understand that 90 percent of advertising is garbage, and it’s pollution. That’s why I like to operate in the 10 percent that’s actually trying to do something better.”

Michael Lebowitz of Big Spaceship explains that his philosophy is “take care of each other” combined with the concept that the “company is the canvas.” In other words, every employee is a creator and artist. Lebowitz provides an interesting concept to managing for creativity and developing one of the best creative climates within the marketing communication and advertising industry I have come across. The teams at Big Spaceship are responsible for figuring out how to accomplish the work that needs to be done and to deliver the creative products and solutions for which their clients are looking.

The two concepts provide a philosophical framework that enables and, at the same time, challenges employees to be creative and to live a creative life that goes beyond the domain knowledge of the specific discipline in which they work. Lebowitz says that his philosophy has developed over time. He also acknowledges that each individual employee plays an important role in his organization. He is keenly aware of the duality between the individual and the group. “It’s how people interface with each other,” he says. “So the individual is obviously part of a wildly important component, but it is a component; and openness to others’ points of view, and then willingness and an interface for collaboration with people who do other things and have other crafts. Those are the primary things … for me the thing that makes … great things in innovation come from great things bumping up against each other. Because the actual creativity in my mind, how I think about it is what emerges out of the connections between people rather than what emerges out of a person.”

Andrew Deitchman, the CEO of Mother New York, says that his overarching agency philosophy is “unlocking creative potential.” Like the other agencies that I interviewed, Mother New York holds creativity at the core. But Deitchman uses creativity for something beyond advertising and communication. Mother’s purpose lies in unleashing creativity where it does not yet exist, be it among clients, consumers, products or everything surrounding them. “Did we unlock something?” he asks after each creative production. “Did we unlock creative potential in this brand, in this individual, in a company, in ourselves, in some way?” Mother is constantly weighing whether or not they achieved that goal, and, if not, how they can redo or make adjustments.

Deitchman also sees Mother as part of redefining the changes currently going on in the advertising industry. Instead of calling Mother an advertising agency, Deitchman uses the term “a modern creating company.” As a long-term goal, Mother wants to be better known and more relevant to creators on a very broad scale. Deitchman draws a comparison to Goldman Sachs in the financial services industry and to any parents’ positive reaction when they hear that their child got a job there after graduating with a finance degree. Ten years from now Deitchman would like Mother to become the Goldman Sachs of the creative realm.

“Whether a kid is coming out of journalism school or film school or design school or architecture school or something involving technology and so on, and he tells his mom and dad his first job is at Mother … ’Oh, my God, I’m so happy for you!’ They know what that is. They are excited for him because our brand becomes this celebrated company that has very wide, very open arms to a very broad group of creators. Because we’ve always embraced the fact that the definition of us as a company is incredibly broad. It’s more about attracting the most creative people and the output could be anything,” says Deitchman.

He sees Mother continuing to expand because marketing and entertainment are becoming the same thing, because public private partnerships are happening, and schools and playgrounds are going to be funded by brands, and because of how Mother integrates technology at a festival to provide people with the best possible experience. “It needs to be something interesting and creative, and it’s going to bring together a very diverse set of minds. People who are tech people, people who are architects, people who are writers and storytellers. The company will be made up of many different types of creators, who are going to need to come together in interesting ways in order to be successful and because of this, there’s a potential for much invention to happen. I think clients will be coming to companies like us for outsourced innovation, in a much broader way, not just for ad campaigns, particularly as they are bringing more and more of that in-house. And so we have to think of ourselves as this very broad sort of creative magnet and creating company, not a company that’s going to create messages for clients or create bespoke content based on paid media,” notes Deitchman.

Mullen’s philosophy, “Advertising Unbound,” represents a culture that is “entirely about limitless possibilities and a relentless belief in a future that is bigger than the past. It is how we started our company. It’s how we built it. It is how we continue to evolve and innovate.”32 Edward Boches reflects on how and why this philosophy was developed. “We used to have a line, which was ‘Relentless creativity that built brands and businesses.’ And we got rid of all that and we came up with one word: unbound. And we have that embedded throughout the company in whole bunch of ways. We have a piece of artwork upstairs in the café. The word is on our business cards, and the word is in every video that we do, and the word is spoken throughout the company. All it essentially means is that you have to be open-minded to anything as a potential solution. You can’t be bound by tradition, you can’t be bound by advertising, and you can’t be bound by the idea of thinking we’re in the business of making a message. You have to believe that the solution to a marketing problem or a creative problem or a client’s objectives could be anything. It might be a new product that we invent for them. It might be a digital experience or a platform. It might be an iPhone app. And I think we probably came up with that word approach because historically we were a traditional ad agency that made print ads, radio spots, TV spots, etc., and that was in our muscle memory as the product that solved every problem, and sometimes institutional muscle memory is hard to change. You can’t change it in increments; you’ve got to leap way over here and say, ‘This is the new target.’ And when we put that word into effect and tried to change everything by aspiring to that as something we wanted to reach but also something we wanted to change,” says Boches.

The Mullen example represents the way in which an organization’s philosophy can permeate everything, and everyone who works there becomes the glue that holds it together. It is clear that unbound is a concept that is ingrained in everything that is done at Mullen and is the driving force behind the creative work that is being produced.

Martin Williams’s agency philosophy centers on people, relationships and the right climate.

For Off Madison Ave, creativity is truly at the heart and soul of everything they do. According to Roger Hurni, creativity is a hodgepodge of personal and work experience and personal opinions. It is all about allowing employees to dig out what the best ideas and solutions are for their clients’ problems. “It’s messy and it’s unstructured and it can be sort of difficult to navigate to a point where we have something we want to put in front of a client, but at the same time, it sort of works for us,” says Hurni. That is why Hurni has added an overarching philosophy that holds the messiness together. “Our mantra is outthink, outperform. And so we try very hard to hire and inspire people to be better than they are and to be a part of something larger than themselves. If they can do that they’ll find their own sort of gratification and their own careers take off and it sort of feeds into itself in terms of being very motivating and very creative in its approach.” According to Hurni, the focus on creativity paired with his philosophy has allowed Off Madison and its employees “to not just go with the flow, but to zig when everybody zags.”

Marshall Ross of Cramer Krasselt has a simple overarching agency philosophy. “It’s a popularity contest. And the brand with the most friends wins. Done. So we try to build brands, and we try to make work and deliver ideas for brands that are inherently likeable and that are built for helping brands not just to transact business, but literally build a friendship base, because brands and, most of all, friends have friends.” In order to achieve this goal of getting the most friends for his clients, Ross utilizes creativity as much as possible. “It’s our product. And I think what’s important for an agency is to recognize that the definition of creativity needs to be very open. If we don’t bring creativity, we don’t bring surprise or novelty to readjust the positions.”

According to Ross, his overarching agency philosophy and focus on creativity will allow him and Cramer Krasselt to not only adjust to the changes happening in the advertising and marketing industry but also to be a better leader. Ross says, “This is the most interesting time to be in business. So you just have to be in front of those changes … you’ll have to deconstruct those walls all over again and with a much quicker life cycle than anyone would have thought. You have to sort of embrace the fact that, almost like the fashion industry, you are on a never-ending journey of change, and the journey is going to go up and down and sideways and, you’ve got to be the right where the change happens. Or you’ve got trouble.”

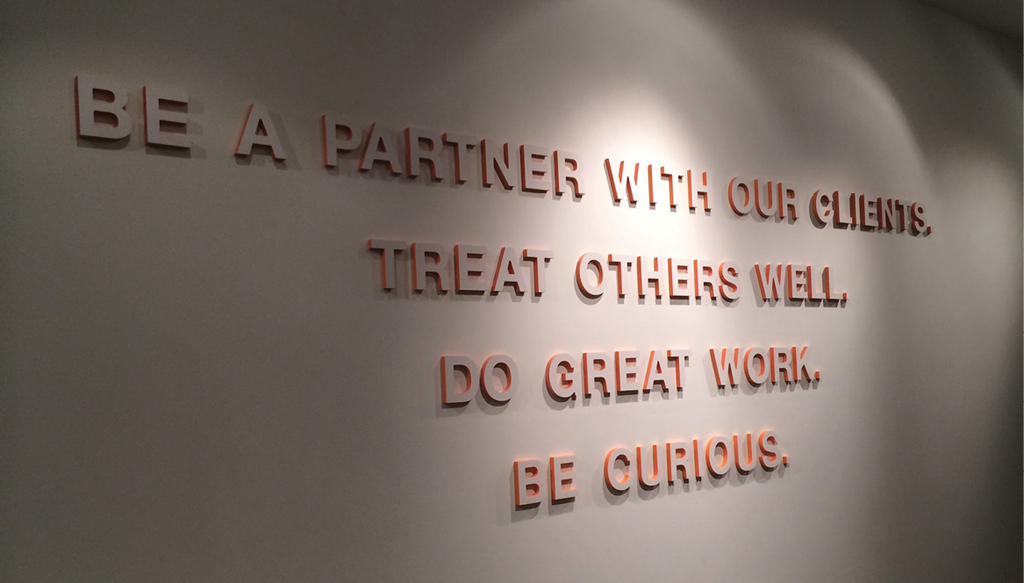

Martin Williams’s overarching agency philosophy centers on people, relationships and the right climate. The agency philosophy hangs on the wall in the office in big letters and serves as a constant reminder of what is truly important to the organization. “Our philosophy is what’s on that wall,” Tom Moudry says. “We do have an overarching agency philosophy and we try to be collaborative and partners with our clients. I think if you’re not it’s very difficult to get good work done. We treat others well, we do great work and the last thing on our lobby wall is ‘Don’t be grabby.’ And we say that humorously, but I mean it. There’s a lot around here, and we’d rather have somebody steal a laptop rather than suck the energy out of this place. And one negative person can do that in a culture. I will help you steal a laptop over the weekend but don’t steal our momentum or our enthusiasm. And people can do that—one person can have an extraordinary and devastating effect on the culture.”

Susan Credle mentions the consumer perspective when she explains the agency philosophy of Leo Burnett. HumanKind is the guiding principle that makes everyone in the agency consider how consumers will feel when they are exposed to the creative product of the agency. HumanKind allows the agency to look beyond any facts and features a brand might have and focus on the benefits that people experience. Credle says, “Brands exist to make people’s lives better in some way. It might make you hipper or cooler, or tougher, or stronger.” HumanKind helps Leo Burnett in their quest to find the true purpose of a brand. Credle adds, “I think HumanKind is so important because it leads to better creative work. But I actually think it serves as a guide for the company.”

If every brand is challenged to serve HumanKind, the world will ultimately become a better place. The overarching philosophy is closely connected to the ten principles that help Leo Burnett evaluate every idea they develop for their clients. The top three evaluation criteria are the most difficult to achieve, but they clearly include the concept of HumanKind and focus on the impact that an idea has on people: Does the idea change the way people feel? Does it change the way people act? Does it change the world? And HumanKind goes beyond communication and experiences. It allows clients and the agency to have a long-term perspective and to widen the services they offer. Credle says, “So HumanKinds are a brand’s purpose. This isn’t just good for a creative product but is actually good for future forward thinking and where you could possibly go as a business. And if you own that, it’s really exciting. And especially today, when people want to talk with friends and communicate, you have to stand for something.” Credle adds that it is not just about advertising anymore. It is all about doing good and having a cause. “I think that we have the moral responsibility in this business to not only do work that’s good for the brand, but to do work that’s good for the world,” she says.

When I visited Fallon in Minneapolis, I immediately noticed a sign, reading, “We are Fallon.” Chris Foster chairman, regional CEO, Saatchi & Saatchi Asia-Pacific and Greater China and former CEO of Fallon in Minneapolis explains: “[We are Fallon] is a our mantra. You see it, you feel it, there is a sense of pride, as sense of family, a sense of cohesion that goes beyond the task at hand. This isn’t a job to most people: It is a calling; it’s a pursuit. People really believe in the work we do here, and believe in its importance, and believe in the fact that we can change the world, basically. And that’s really, really important.”

“The death of marketing as we know it.” —Anomaly New York

Foster describes the agency philosophy as “our focus to do brave work that makes a difference.” He says that Fallon’s key focus lies on the creative product that the agency produces. Fallon achieves creative results through having a global view of creativity. Foster adds, “Even though we’re based in Minneapolis, we make sure that we have a world view. That’s born out in the fact that we have clients from around the world—we’re doing projects in western Europe, we did some work with Thailand, we work with a bank in Abu Dhabi, and we have a multinational staff of people. So more and more, the world is a global place, and there’s no reason we shouldn’t be working on these types of clients and bringing that perspective to our American clients. Our goal is to do brave work that makes a difference, and we do that through a worldview of creativity.”

Foster sees creativity as something that creates an unfair advantage. “If you have some kind of solution, some creative way of solving a problem that is or can be an economic multiplier, then creativity is a purpose-based thing. We’re not here to make art films. We’re not here to make the world a more beautiful place. We’re here to solve business problems. So there’s a very practical view of creativity that comes with the Fallon proposition, which has got to be attached to a business problem or has to get you to a better place as a result of that creativity thinking. So I think that’s the nature of creativity for this place.”

For Johnny Vulkan, cofounder of Anomaly New York, creativity represents the core of everything Anomaly stands for. He describes his philosophy: “Creativity makes the difference in something having an impact,” and creativity without purpose is just indulgence. Vulkan is not interested in doing something new or crazy for the sake of it or in creating something to impress the industry. He says that “creativity is the holy grail” and that it provides the foundation for conducting a successful business. Creativity allows Vulkan to make positive change and to achieve positive business results for his clients. He points out that his job is commerce, not art, and that creativity must be applied to business problems. Referencing German designer Dieter Rams and English designer Jonathan Ive, Vulkan says the goal is not just to build a beautiful thing, but starting each project with a functional benefit that ends up being beautiful. Every project that Anomaly takes on has to work successfully, and aesthetics are an added benefit. This approach is a reminder of the Bauhaus movement and the belief that “form follows function” or “form follows business success” that is often achieved through originality and novelty.

The philosophy of an agency is largely a reflection of the leadership of the organization. It takes a great leader to be able to home in on the creative potential of his or her employees and to use this power in the best way possible. A highly creative person must develop at least one or more specific domain skills and work hard at developing them. Individuals can achieve creative excellence with constant practice, tenacity and commitment—and by applying some of the concepts introduced in previous chapters. Mastering personal creative abilities is easier and more manageable than developing the creativity in organizations. Becoming a great leader who can lead companies toward creative excellence poses a greater challenge due to the complexity of creativity and the difficulty of managing the numerous factors that can influence the creative outcome.

Highly creative individuals do not necessarily make great leaders in a creative organization. The creativity 4Ps of person, process, place and product—framework provides a foundation for better understanding how creativity works. It may not be perfect and by no means is it all-inclusive. However, it provides a holistic model to look at four distinct dimensions that can greatly influence the creative outcome of any organization.

In order to discover what it takes to be a great leader, we need to understand how creativity happens at the individual level and how employees can be empowered in order to expand on it. The creative abilities of an individual depend on their ability and willingness to think divergently and convergently, as well as the way in which the individual uses creative problem-solving processes. Implementing a creative problem-solving process not only strengthens an individual’s thinking ability, but also provides a framework for an entire organization that will increase the chances of higher creative output. As we have seen in the previous chapter, the physical place and the cultural environment are influential factors when it comes to the creative output of employees and the organization. Being aware of the many factors associated with the place component can provide leaders with managerial tools that can influence and improve any creative organization.

Creativity is complex, and many different factors can influence the outcome of creative people and creative organizations. Since it can be challenging for an organization to achieve creativity, it is important to understand how one can manage and provide leadership for better creative climates. According to Teresa Amabile, creativity cannot be managed, but we can “manage for creativity.” Amabile’s KEYS instrument provides a framework that any leader interested in creativity and innovation can learn and understand. Many executives interviewed for this book confirmed that creativity is the biggest asset they can provide their clients. Advertising executives are beginning to understand that their business is no longer advertising alone, but rather a business of ideas and problem solving.

Based on the interviews in this book, the focus in advertising is moving away from delivering creative pieces and moving toward making meaningful contributions that connect people and brands. Margaret Johnson of Goodby Silverstein & Partners says, “We only want to do the most innovative things. We want to effect culture. We want to be a part of pop culture.” According to Johnson, Goodby Silverstein & Partners has such an impressive reputation within the industry that it attracts only the most creative and talented people. Johnson adds, “Everyone is really driven and interested in doing the very best work.” According to Johnson, people want to work hard because they want to represent the company well, and they want to put the most innovative work out there for people to see.

Motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic, is a key component that influences creativity at the individual level. Any member within an organization, whether they are an employee, a manager or an executive, is influenced by both kinds of motivation. Knowing what motivates creative people and what promotes creative excellence can help a manager adjust the various factors that drive motivation, and ultimately the creative end result.

A creative leader should not only be aware of how these two areas affect his personal engagement, but he should also understand how motivation can influence the creative work of his employees. Susan Credle, chief creative officer at Leo Burnett in Chicago, describes her experience with employee motivation: “When agency people are producing the work they are proud of, they stop talking about money and vacation really fast. So the motivation is the work.” Lynn Teo believes that creatives are motivated by expression. “I think it’s that need to leave a mark on something. I think passion is probably the thing that drives motivation.” says Teo.

Alternatively, Doug Spong believes that the motivation for creatives is not about money. “For all people it’s as much their avocation as it is their vocation. I don’t believe we have anybody who feels like they simply show up to collect a paycheck. Our people here love the art and the craft of what they do.” Blake Ebel approaches motivation from the perspective of support and encouragement. He says, “I want them to be selfish in the sense that I want them to be constantly worried about what great work they’ve made this year.” Ebel encourages his employees to create the kind of work that wins awards and makes them money.

Michael Lebowitz looks for people who want to be doing the kind of work Big Spaceship specializes in or who want to explore and are not necessarily looking for stability and equilibrium as the defining factor for their job. “It’s not that they don’t have the same external motivators as fame and fortune, and all that stuff. But if you asked any given person what their favorite thing is about working here, they would say the team and the culture, ninety-nine times out of one hundred, guaranteed. That’s what real motivation looks like, living up to the team and the culture. They want to pay homage to the people around them; they don’t want to let each other down; that’s motivating. Motivation is a personal thing, and it varies from individual to individual, so there’s no one-size-fits-all answer.”

As I mentioned in the previous chapter, it is important to design the physical place in order to increase accidental collisions and sharing of ideas. All of the creative executives interviewed for this book understand the power of the physical environment and the impact that it is has on the creative work that is produced by the agency. Many traditional agencies have started the process of tearing down the walls in order to create an open and collaborative climate. Blake Ebel, former chief creative officer at Euro/RSCG in Chicago, explains, “We’ve created a real open environment. The actual space itself is very open so there is a lot of energy. You can hear a lot of people running and walking up and down the halls, and I think that’s a good thing.”

Chris Foster, former CEO of Fallon in Minneapolis, says, “Creativity, I think, is just a sense of energy and movement, so even in the way we have designed our space here, you kind of look. We have a round room; we have a central staircase; people have to bump into each other; people have to run up and down; people have to have spontaneous meetings. You have to gear yourself up for spontaneous interactions so that magic can happen. Space doesn’t make an agency, but it certainly helps with energy flow.”

Both executives believe that effective leaders should take charge of the physical space in order to optimize it for maximum creative potential.

The physical and cultural environments also play an important role in supporting the philosophy of the agency. As we have seen in some of the samples, the employees of highly creative agencies seem to be generally happy people and more effective workers if they really understand and embrace the philosophy of the agency. This is the reason many leaders display their agency philosophies in the office, thereby making that philosophy a part of the environment.

As described in chapter eight, several other agencies that I visited redesigned and modified their offices in order to encourage unexpected collisions. As Edward Boches of Mullen says, “I want there to be unexpected collisions, and a lot of them. Even those who have closed offices—they’re all glass, sometimes two people to an office—and you can’t come out of your office without bumping into other people. It makes you realize that everything you do is connected to what everybody else is doing.”

These collisions and run-ins allow for the exchange of ideas at spontaneous and unexpected moments and can result in the production of even better, more innovative ideas. There are definitely benefits to having planned meetings, but these do not allow for as much spontaneity as random run-ins do. Many agencies are trying to create environments that not only encourage open discussion and collaboration, but also encourage the sharing of ideas at unexpected times. David Droga says, “There’s a very structured thing here where, as I said, the strategic planners are engaged very early. We make sure that people are having lots of conversations. So the idea is not just in a complete vacuum. It’s not just thrown in a sandpit and like ‘Hey, let’s see what comes out!’ There are lots of conversations and thoughts. We’re a corridor conversations type of place. There are more interesting things reeling ahead in the most unlikely of places.” Droga says he loves the contagious nature of creativity “when it’s free-fall and freestyle sort of talking and conversations. Just casual, I think the best stuff comes from casual [interactions]. It’s not forced. You can’t force creativity. You can’t force collaboration. I just feel like [it is important to] create a safe environment.”

Tim Leake, former creative director at Saatchi pointed out, “It’s sort of a shame that we don’t somehow get like-minded people together, because we can get great things to happen by doing so. At Saatchi we sort of have an open space, but open space with desks and lots of meeting areas, which works okay. It’s not enough to be this ‘let’s collaborate in the hallways’ kind of mentality, and not quite closed enough to feel like I’ve got privacy.” An open space in itself does not make a creative climate.

Michael Lebowitz of Big Spaceship has spent a lot of time thinking about the way in which his employees are seated and how he can influence and improve the way in which knowledge is shared and projects are managed. For years, the interactive industry has been faced by the challenge of creating multidisciplinary teams and integrating specialty knowledge—ranging from visual design, navigation design, user experience design, information architecture, concept development, strategic planning and consumer insight to programming, systems engineering, coding and project management. After rearranging the way his employees are seated several times, Lebowitz finally developed a model, where people of different skills are seated next to each other and can communicate in order to share the knowledge necessary to create the best possible solution for a client. The physical attributes of an agency then influence the way people interact and collaborate with each other.

Lebowitz thinks that the reason people work at Big Spaceship is more about getting to work with each other than it is about getting to work with the things that come in from outside. He has worked hard at providing the right environment that makes the agency inherently motivating and inherently exciting. He also points out that letting people be themselves and allowing them to have a sense of autonomy plays a big role in how the work gets done. “I don’t tell people how to get their work done. I just say there are these values that we have, these five principles, and if those five principles are in equilibrium, I’m happy, and the business will be successful, and the rest is completely up to you. And that has stood us in good stead for a long time,” Lebowitz says.

“One of the things we’ve done in many of the thinking areas is knock down walls and doors… and I think some of your best thinking, best interactions happen in hallways outside of offices and over thinking tables,” says Marshall Ross, chief creative officer at Cramer Krasselt in Chicago. In addition to maintaining an open environment, it is also important to collect as many ideas as possible within an organization and to allow every employee to participate, no matter what their discipline or rank. Ross adds that “One of the things we do here is we keep the environment very open; we keep the work very exposed. Work in progress is always out in the open for people to see because we kind of want that constant level of critique. We want people constantly wondering if this is good enough.”

The open space environments and increased sharing culture also allows for filtration of good and bad ideas. Margaret Johnson of Goodby Silverstein & Partners speaks to the concept of “fail faster.” In an industry where ideas, creativity and innovation are the raison d’étre, the generation of many ideas is not the only thing that counts. It is also important to establish a process that filters out good ideas from the ones that may not be as good. Mark Hunter, chief creative officer at Deutsch LA, says, “I kind of believe that ideas should get out in the open and they should get some air and some sunlight on them. If they’re going to grow, they’re going to grow, and if they’re going to die, they’re going to die—the sooner you find that out, the better.”

Several leaders interviewed for this book encourage rapid prototyping and testing so that bad ideas can be identified earlier in the process. Displaying ideas on the walls throughout the agency instead of showcasing awards is a practice at Mother New York. Andrew Deitchman says, “If you come into our space, you’ll see our works in progress surrounding us. That anybody who kind of walks up is like, ‘That’s really cool’ or ‘Oh, I’m not sure about that.’ Everybody is surrounded by unfinished work. [However], a lot of other agencies that you visit display, a cabinet of awards, and there’s a loop playing of finished spots. For us, it’s graphs of paper constantly up against the wall.”

This helps Mother create an environment where ideas are expressed and shared early in the life of a project. It’s also part of Mother’s culture to change an idea and improve any project up until the last minute. “I think there are some organizations that are great with, ‘Oh, that’s a terrific idea’ there are some organizations that are so focused on the end product in a pure sense. For us, nothing is done until it is done. So a big part of it is an appreciation for the craft. We ask: Was the writing perfect? Can we tweak this? Could it be better?” says Deitchman.

The postmortem is another excellent tool that any creative leader can use to better manage the organization and its creative climate. In order to stay profitable and successful, most companies have to focus on a specific number of services. This often leads to specialization and the repetition of the same process based on its initial success. Even in fascinating and exciting industries like marketing, advertising, film, media and entertainment, where creativity is highly important, standardized production processes and procedures can lead to less creative experiences for employees. Individuals working in creative industries are typically curious. Therefore it is important to encourage as much creativity and freedom as possible. Typically they have an internal desire to learn more and are inquisitive about their surroundings and the world, just like Curious George developed by Hans Augusto Rey and Margret Rey.33

However, as a learning organization, it is important to manifest and embrace this concept on a larger scale and to continue to be curious even when things are not working well. Being conscious about what projects have and have not worked in the past is the first step toward creating an environment for continuous learning. Everyone at Pixar is asked to get more out of postmortems. This requires several people or teams to take a closer look at every project and analyze the elements that worked successfully and which ones did not.

During these postmortems, it is important not only to acknowledge the successful elements of a project, but also to recognize any mishaps and mistakes that were made. If the negatives are ignored, these sessions will not be nearly as productive and helpful for the future. One suggestion made by Catmull in his article, “Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity,” is to vary the way in which these postmortems are conducted. He advises participants in the postmortem to think of five things that they would do again and five things that they would do differently in order to have a balance between the positive and the negative aspects of a project.

Twyla Tharp, world-famous choreographer of Movin’ On, provides a similar framework, which she calls “concept of failure.” In her book The Creative Habit, she says that it is important to be willing to fail and not to deny failure. In the end, failure can provide us with great opportunities for instigating change and progress in an organization, as long as both are welcome. This is a concept that is important in other contexts as well, including classroom projects. Rather than allowing an often-misguided need for “perfection” to drive us, we should reflect on our work and analyze what makes it successful. We should consider what could be added, changed or removed in order to make it better. By embracing failure and approaching a problem with a more realistic outlook, we can come up with bolder ideas that we would not have come up with otherwise.

Margaret Johnson embraces the concept of failure when she develops creative work at Goodby Silverstein & Partners. In order to create original and innovative concepts, many agencies are taking risks and pushing themselves, their employees and clients. Johnson fosters a climate in which failure is accepted and discussed openly. Doing so minimizes the risks that exist for agencies that are constantly trying to push the limits of what has been done before. “One thing that we have been saying lately is ‘Let’s try to fail fast.’ Let’s come up with a lot of ideas, do it quickly, and realize early on that it is not going to work so we can switch gears. You don’t want to spend a ton of time on something and find out six months later that it was a bad idea,” Johnson says.

Postmortems require that one accepts failure and then analyzes what went wrong or what could have been done differently. Postmortems are an important aspect of learning environments. Postmortems provide an opportunity to take a step back and assess what worked successfully and what needs improvement. Idea development, prototyping and the launching of new products are usually the most exciting activities in creative companies. However, being innovative all the time can be difficult economically, since the rewards for outstanding ideas are usually financial. Bettina von Stamm illustrates this in the Creative and Implementation Cycle in her book Managing Innovation, Design & Creativity. If managers used postmortems more frequently, employees would experience the sweet spot that exists between rules, procedures, routine-and-known solutions, constructive reviews, challenge, developing new solutions, commitment and experimentation. This is the bridge (or the mental space) between daily job activities and the exciting projects someone might get involved with based on the cognitive surplus. Identifying areas and projects for cognitive surplus within the organization can foster success, commitment and opportunity for small changes on an ongoing basis.

Freedom and challenges are two topics that emerged during my interviews and can be analyzed from a managerial perspective. Across the board, everyone interviewed encourages their employees to have as much freedom as possible and to pursue different kinds of ideas without many parameters. Many leaders say they give their employees the freedom to solve the problem at hand however they see fit, but they make themselves available for support, if needed along the way.

Rob Schwartz of TBWA\Worldwide and formerly of TBWA\Chiat\Day gives employees the freedom to do anything necessary to get the job done. He tells them, “Don’t be afraid to be a genius.” AKQA gives its employees tremendous freedom in terms of how they approach a problem. Lynn Teo says, “There’s no right or wrong way in how they like to work.” Doug Spong of Carmichael Lynch Spong in Minneapolis speaks of freedom in the workplace slightly differently and says, “I think we know that if we’re not a little uncomfortable in terms of the ideas sometimes we’re not testing the boundaries of that. So we do encourage people to test the perimeters and see where those boundaries may be for a client’s brand or for ourselves for that matter.”

However, freedom also comes with responsibility and accountability. Blake Ebel says that in his agency, creatives have a tremendous amount of freedom to own projects, to make them their own and then to make them great. “Putting that responsibility on them then holds them accountable for [the project],” he says.

David Droga expresses the duality of freedom and challenge by saying that he gives his employees freedom “as much as possible without becoming a free for all. Freedom with context.” He also says that “we challenge ourselves to stay relevant, to stay fresh, to not fall into a trap of familiarity, and creativity is one of those things that sometimes people, they find that they find a lane, where there’s fruit, and they just stick to it and such is the nature of creativity, it can’t be contained and can’t stand still.”

Fallon in Minneapolis provides employees with a written document that outlines the agency philosophy and consequently becomes challenging. Chris Foster, former CEO of Fallon says, “The challenge comes in through settings—setting the goal. So we have defined our purpose, which is a one-page document, which then sets the bar for employees, their understanding that that’s where we’re going. Then everyone is responsible for creating their own purpose.”

The interviews brought to light the fact that many agencies not only encourage collaboration within the agency, but also foster an environment where employees can utilize external resources. The advertising industry and the work generated by agencies have become more complex and require the skill sets of a hugely diverse workforce. Many agency executives acknowledge that it is almost impossible to employ every skill needed in order to produce the work that is expected of them. Therefore, agencies look within their own networks, such as the branches in other places of the world, as well as to outside specialists. This ensures that the best possible skill set can be brought in to meet the challenges an agency is facing.

Several agencies represented in this book are doing even more than employing the talent of their employees. They help introduce new skills and create opportunities for their employees to get inspired or learn something they otherwise never would. Goodby Silverstein & Partners invites musicians to play concerts and comedians to do stand-up routines. Other agencies employ poets and artists to come into the office to bolster the creativity and ideas of their employees.

Creative leaders are no longer bound solely to internal resources. With many platforms available, anyone can tap into talents elsewhere, whether they are from a different country or a different discipline. This open access to talent has lead to internet platforms such as Behance, a creative network that allows people to display their creative work. Victors and Spoils, an agency created by a former executive of Crispin Porter + Bogusky, is focused on the principle of crowdsourcing. Victors and Spoils manages the creative output and talent of many individuals, not just the ones in the agency itself. They consult with clients, develop a strategy and seek outside talent in order to provide the best execution of ideas.

All executives who were interviewed for this book confirmed that employees are the most crucial resource for any creative organization. Rather than trying to maximize employee productivity, it is important to balance work with fun, play and self-realization. Companies like Google have been known for allowing their employees to spend 20 percent of their time on personal projects. The daily pressures of the business and the growing demands of clients can make it challenging to have non-billable projects at an organization. However, Clay Shirky points out in his book Cognitive Surplus that engaging in something meaningful is a basic human need. The many examples featured in his book are proof that anyone can seek work outside of their daily jobs in order to find and engage in projects that make them feel free and challenged. Companies have to pay attention to this need so they don’t lose valuable employees with excellent skills due to the fact that the employees are not provided the perfect balance of personal needs, company pressures and overall job satisfaction. Andrew Deitchman of Mother New York is very conscious that his employees need change and stimulation paired with challenge on an ongoing basis. He knows that unless he provides his employees with the most interesting and challenging work, they will apply their cognitive surplus somewhere else.

Big Spaceship’s philosophy centers on collaboration, relationships and openness.

“If people aren’t creating and making on a creative basis and seeing their work out in the world, to have their thought out in the marketplace in a reasonable amount of time and we’ve resigned clients because that just wasn’t working,” says Deitchman. This is one of the reasons why Mother takes on a broad spectrum of interesting, diverse and challenging projects that require different skills that are typically not found in traditional agency settings. Mother considers itself not just an advertising or communication agency but a “modern creating company” that has its own design practice, organizes rock concerts, develops products and creates communication campaigns. The typical projects that Mother accepts must provide sufficient stimulus for its employees. This provides big opportunities for employees to push their own abilities further.

Deitchman described a smartphone application that his company created and will be released as an online game. People who have seen it were blown away and surprised that the app was not created by a Silicon Valley Startup. To Deitchman, this demonstrates why challenge is important and good. “When we do things like that, it just shows to people that they need to constantly challenge people to bring their A-game and also to bring ideas that they have, that don’t even relate to clients, because maybe their ideas can be applied to clients or maybe not applied to clients because anything is possible. You know, when you’re told ‘This is your job; this is the box you are in,’ and you’re not shown things that go far outside of that, you’re not challenged because you’re basically saying, ‘Well this is my job; this is what I have to do.’ When you are constantly exposed to things that are really, really interesting that go way outside of the typical realm of your job, if you don’t find that to be challenging and want to be a part of or create the next one, then you probably shouldn’t be here.”

At mediaman an old space heater was repurposed into an interactive printing device for last-minute recipes and shopping lists.

“Evolve or become extinct like Dodo bird” is part of the Martin Williams’ agency philosophy.

Creative leaders must also allow employees to apply their creative talents to projects that are unrelated to their daily assignments. Michael Lebowitz of Big Spaceship has high regards for his employees and believes in their abilities to solve problems. Ever since Lebowitz established “Hack Days,” a twenty-four–hour marathon during which the agency goes offline to client work, he has been even more amazed by the output, quality, and volume of his employees. During a Hack Day, the entire agency comes together and starts an ideation process during which anything can happen. Someone might want to work on improving a specific process within the agency or to develop an idea for a business or product they have always dreamt of. These marathons are intense and focused. Different talents and skills come together and some amazing and beautiful stuff is created.

“The most recent Hack Day, I announced that I wanted to reinforce the ‘company is canvas concept,’ so I announced that the next Hack Day was going to be Hack the Spaceship,” and they could take any aspect of this company and optimize it, improve it, make it better. They could just make something more fun, more meaningful, and it was really wide open. I didn’t say how the teams had to organize; it was just however they want. We ended up with about ten teams including one team of two digital producers, and the producer team took our expense reporting process and optimized it, saving people tons of headaches. They became an expert in it, so they are now a resource to everyone, and they delivered a presentation that was unbelievably funny. So they took this very mundane, pragmatic thing and made everybody’s life easier. They also really impressed people with their ability to present something that made for a very engaging subject.

“Other people did art projects; you know, here’s an installation in the office based off things that are true to our culture, sort of physical computing projects. You know, if you walk through the door and have an RFID tag it plays your theme song, a lot of really beautiful things. Systems for getting more new people in the company, sort of socially acclimated and included more quickly, just beautiful things and that happens. They’re not afraid to dive in and do those things. Part of the reason is I say, ‘I want to see whatever you’ve got, so they bring what they’ve got,’” explains Lebowitz.

At mediaman, a digital marketing agency that I cofounded with two other partners, we have introduced similar activities during the last three years. During the “little creative project” series, a team develops ideas to promote a move into a new office location. Twenty-two employees from different disciplines, possessing diverse skills, came up with a reinterpretation of the classic arcade video game “Pong” and created “Bitball34”, an interactive game where pedestrians in the German city Mainz became part of a life-size “Pong” game. Aspects of street soccer were added and integrated into the virtual components of “Pong” to allow participants to physically play as the two paddles returning the virtual ball back and forth and to experience the gameplay.

Another “little creative project” resulted in the creation of an on-demand recipe printer called “Dshini35”—that represents the German pronunciation of the helper “Genie in the Bottle.” During the initial project phase, the participants identified some personal challenges they often experience when leaving the office late. Several employees mentioned that their refrigerators are often empty and that they need to go shopping after work before cooking a meal. Others mentioned the difficulty of knowing what to cook and the right ingredients to select. The team ended up developing a concept that turned an old wall heater into an interactive printer that allows users to print out a recipe with a shopping list of the ingredients.36 The project was implemented over several weeks and now allows employees to spontaneously choose a cuisine and print recipes that come with shopping lists and time of preparation.

All companies interviewed for this book are embracing creativity and are working hard at shaping the future of the fast-changing industries of advertising, communication and marketing. Creativity has become the main tool that allows each agency to solve their clients’ business challenges and to set themselves apart from their competitors. Many executives interviewed understand that their business purpose is not only producing great work and serving big clients, but also aligning their business with their employees’ needs and desires. Several agencies select their clients with an eye toward providing their employees with the opportunity to engage in diverse projects and use their individual skills and talents in multiple ways. Anomaly, Droga5, Big Spaceship and Mother New York seem to be the furthest removed from the traditional advertising industry—the Mad Men era. Instead of creating new factories to churn out massive advertising messages, founders like David Droga, Andrew Deitchman, Johnny Vulkan, Michael Lebowitz and their respective partners and employees are engaging in a new kind of company that combines marketing and strategy consulting with the modern tools available to professional communicators. David Droga says that he wants to be part of that change because “No one has the answer; the industry is stuck in two levels. There are those that are pining for recovery, which I think is dangerous. I think we’re trying to push it to reinvention. Not reinvention of the purpose of the industry, the mechanics of the industry; but reinvention of how we do it. I think it’s an exciting time.”

The creative product of those new advertising agencies or “creating companies” no longer is limited to advertising or PR efforts. Creative production literally can be anything from the traditional thirty-second commercial to the rock concert to the smartphone application to the television show to a new product, new distribution channel or even a new business. Johnny Vulkan sums up the trend: “It’s the old ‘to a hammer, every problem is a nail’ problem. To an ad agency, every problem [needs] an ad to solve it. Looking into the future, a pyramid where advertising sits at the top and everything else has to follow sequentially to the bottom will no longer represent the industry.”

Create a mental image of where and how you see yourself personally within the next year. Use magazines, newspapers, art supplies, items found in nature and paper, and create a collage that represents your idea visually. (This exercise can be repeated regularly).

The world is becoming increasingly visual. In order to communicate effectively we need to come up with innovative, original and creative ways to show familiar concepts in unusual ways and unfamiliar concepts in familiar ways. Visualize Connection with 9-12 images/key visuals.

The presentation can be produced in an abstract, concrete, symbolic, descriptive way and/or can also make use of analogies. The key visuals can be in relationship with each other, e.g. tell an overall story or script or can be independent from each other.

This assignment should encourage you to be playful, take risks and experiment (try out new things you might not even think of).

The key visuals should have an appropriate size to address an audience of 6-10 people. You can use any visual design tools and/or elements available to you, e.g. Photography, Painting, Drawing, Collage, and Objects.

A city or street map represents the earth in a two-dimensional way. Based on the idea of a street map, present your daily path: the way from home to work (or school) in 9-12 images/key visuals. Consider the use of elements that are related to maps such as symbols, directional information and topographical information.

The map, in form of a visual guide, represents the basics for developing personal problem solving strategies. You can develop innovative solutions or visualizations that go far beyond the traditional concept of a map by

You can use any visual design tools or elements available to (e.g. photography, painting, drawing, collage, objects). This assignment should encourage you to be playful, take risks and experiment (try out new things you’ve never tried before).

The key visuals should have an appropriate size to present to an audience of 6-10 people..

Note: The special aspect of this assignment lies in the connection of two points of travel and its visualization separated by elements of time. The simple information “going from a to b” should be moved into the background: The how is what’s important and not the what.

Adapted from Wilde, Judith, and Richard Wilde. Visual Literacy: a Conceptual Approach to Graphic Problem Solving. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1991.