Having been brought up on a bedtime egg-cupful of Little Bricky throughout my formative years it took me a long time to actually learn to like beer. Little Bricky was a barley wine fromour local brewery, Brickwoods in Portsmouth, and nasty enough to put most people off beer for life. For many years I was a dedicated lager drinker, eschewing the heavier flavours of beer. But at the behest of incredulous friends I made valiant and ultimately successful attempts to appreciate the finer points of beer. Now I can hold my own at CAMRA meetings, talking knowledgeably about Munich malt, lauter tuns and diastatic power, and sincerely I think I have finally recovered from all those Little Brickies.

The great thing about making your own beers is that you can make them to your own taste. I regularly make my four favourites and start to get nervous if stocks run low. Even though I am content with these, I still experiment when a friend suggests a recipe or I have a bright idea. I suggest that you try a few of the recipes in this chapter, then stick to the ones you like. I give the basic theory and techniques of beer-making and recipes for a wide range of types – from beer you can give to toddlers, to stuff you can use to fix the shed roof.

The word ‘beer’ is a slippery creature whose meaning changes from person to person and from age to age. Historically it has been used for any undistilled brew which does not involve grapes. If it had grapes in it then it was wine, if it did not then it was called beer or wine fairly interchangeably (the strong beer called barley wine being a small memorial to the old usage). The difference between beer and ale is similarly movable. Although both are made from malted barley or other cereal, beer (in the sense of something made from cereals) was an ale which used hops instead of, or in addition to, the various traditional herbs which had been employed previously. Nowale seems to have taken on the meaning of ‘a good beer’, presumably in contrast to boring, ordinary beer.

The main topic here is beer in the sense of an ale with hops but I will also touch on ale in the older sense of a grain-based fermentation flavoured with herbs. In addition I have some beers in the ancient sense that could arguably be called wine but are still commonly referred to as beer, nettle beer being an example. Things could not be more clear.

A glance at any book dedicated solely to beer-making, or a few minutes spent in the company of a brewing enthusiast, will convince the uninitiated that this is a black art, more at home atop a Gothic tower than in a kitchen. All the brewers I have met are men obsessed (and they have all been men). They talk animatedly and sometimes darkly about unfermentable sugars, degrees Lovibond, EBUs, SRM and the relative merits of CaraMunich Malt III and CaraMunich Malt I.

How much of this esoterica do you need to know to brew beer? Ultimately none at all – all you need to do is follow a recipe. But it is interesting and useful to learn about what is going on, not least so that you know how important it can be to stick closely to a recipe. When the temperature for the mash is given as 66°C the writer means 66 degrees and for good reason, and when a particular hop is specified you cannot easily replace it with another; it would be like substituting sprats for haddock in a fish pie.

Of all the home brewing I do, beer-making is the most satisfying. When making beer you feel that you are doing something important, something that makes the world better. How right you are. It is an artisan pursuit and, as someone who has been a furniture maker, I feel completely at home. Beer can be ready very quickly – 3 weeks or even less for some brews – and always much quicker than wines.

Many of the beers that follow use a range of wholegrain techniques, some of which are little used by even the dedicated home brewer, such as using a single mash to produce two or more beers (parti-gyling or split-gyling). I also give several recipes that use malt extracts, which avoid much of the hard work associated with wholegrain brewing.

Krausen or froth after 2 days of fermentation

Malt: the basis of beer

Alcohol, as we know, is produced by yeast acting on sugar (see here for a full explanation). Beer is made from cereals, usually barley, that contain small amounts of sugar but large amounts of starch. A considerable part of the beer-making process is spent converting that unusable starch into yeast-friendly sugar.

When a barley grain absorbs moisture it starts to germinate. This produces enzymes, which begin to convert the starch within the grain to sugars – sugars that are destined to nourish a young plant. If we wanted barley plants we would let nature take its course, but we do not, so the germination process is stopped at a very early stage by heating and drying, effectively killing the grain but leaving the enzymes intact. This leaves the grains with a barely depleted starch content, and with a sufficiency of newly created enzymes to convert this starch into sugar. It is with these dried grains, known as ‘malt’, that the brewing process truly begins.

Crystal malt

Wholegrain and extract brewing

There are, in effect, two methods of making beer, though they can both be used in a single brew. These are ‘wholegrain’ in which you start with grains, i.e. malt, and ‘extract’ in which you start with malt extract – the sugars and the flavours having been industrially extracted from the malt.

Wholegrain For this style of beer-making, you use a process called mashing to convert the starch in malt into sugar, followed by sparging to extract the sugar (see here for more details). This method gives you complete control over the beer you make and I quite like the challenge of big kit and the complicated processes it involves; I feel I deserve the resulting beer a little more. Purists will always opt for wholegrain brewing but you only have yourself to please so do not be pressured, even by me, if you do not wish to take that path.

Extract Extract beers are also derived from malt, but the complicated process of converting the starch to sugar and extracting the sugar has been done for you. With extract brewing your starting point is tins of sticky malt extract or packets of dried malt extract powder.

Malt extract beers miss out the mashing and sparging processes which occupy so much of a brewer’s time. They also miss out some of the kit. You will need only those pieces of equipment required for the boil and beyond. This method also allows you to make strong (high gravity) beers more efficiently than in wholegrain brewing, where large quantities of partially used grains either have to be thrown away or employed to make a second, weaker beer. What malt extract beers cannot do is provide you with the full depth of flavours you get when making your own mash, where you can control the types of sugars extracted. It also feels a little bit like cheating, but perhaps that is just me.

Making extract beers saves so much time and hard work that it is the only way many people brew their beer. After mucking about with wholegrain brews for years my father was eventually lured to the dark side. He made hundreds of gallons of beer this way and, being more interested in saving money than finding a way of filling time, never regretted it. Extract brewing is the method you would be using if you bought a beer-making kit; there is nothing wrong with kits – they make excellent beers – they just take a little of the fun out of things.

Some brews use both malts and malt extract, sometimes employing a malt extract as the base malt (providing the bulk of the sugars) and special malt for flavouring and colour – and in the particular case of crystal malt (see here), for sugar as well. Malt extracts are also used in addition to grains in wholegrain brewing to increase the strength of a beer.

The method

Here is a general description of the beer-making process. Extract brewing misses out the first two steps (see here), which may not seem much of a help but it is. Lager-making follows the procedure up until fermentation, after which the temperatures and timings are quite different.

Mashing Malted barley grains are steeped in hot water, activating the enzymes they contain. These enzymes then convert the starch in the grains into fermentable sugars and some unfermentable sugars. The thin porridge-like mixture is called the mash and the bucket where the magic happens, the mash tun (pic 1).

The temperature at which the enzymes work best is 66°C, and the conversion process typically takes 1¼ hours. It is very important (it really is) to keep the mash at around 66°C using blankets and duvets, because the chemical reaction slows to a crawl if the temperature drops too much.

Straining The sugar solution is filtered from the mash, leaving the grains behind. To do this, the mash is poured into a fermenting vessel which has holes drilled in the bottom and has been lined with a nylon mash bag. This is set on top of a large bucket, into which the sugar solution (wort) runs (pic 2).

Sparging The amount of wort collected in this way is small and very high in sugar. It is possible to make beer out of it, but not much and it will be very strong. There is still a great deal of sugar in the mashed grains and this needs to be extracted. This, combined with the extra water needed to achieve the extraction, will give a wort with the correct sugar level. The standard method is sparging, where hot water is slowly sprinkled over the grains until the volume of wort required is achieved and most of the sugar extracted. I suggest a variation on this technique which I still call sparging though, technically, it is not: Water is heated in a large pan to about 78°C and, using a plastic jug, carefully poured over the grains in approximately 2-litre batches, flooding the grains. The wort slowly trickles through (it takes about 10 minutes) and the process is repeated until the required amount of wort is collected (pic 3). The grains are discarded.

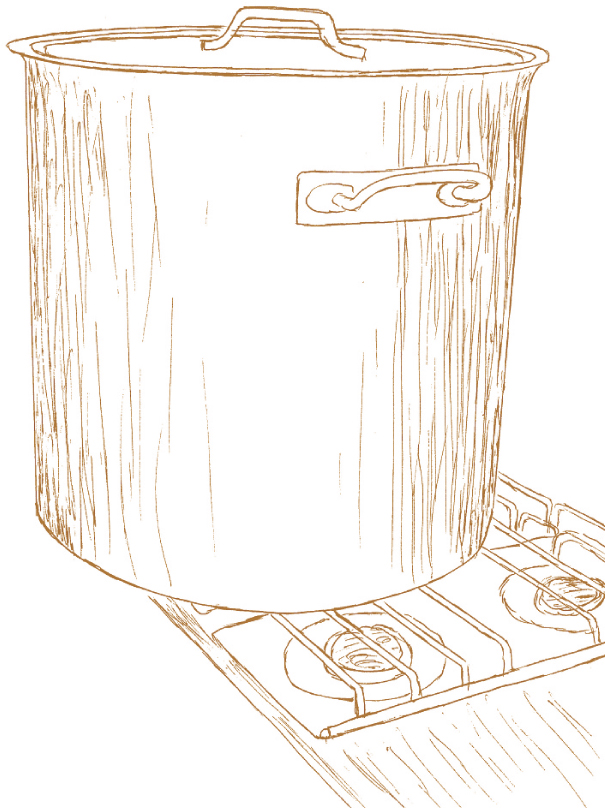

Boiling The wort is boiled for about 1½ hours (pic 4).

Adding the hops and other ingredients to the boil At the beginning of the boil (copper-up), hops are thrown in. Hops added early impart bitterness to the beer; hops added towards the end lend aromatic flavours. Other flavour ingredients and additives such as copper finings can also be added at various stages during the boil.

Standing To extract the flavours the wort is left to stand off the heat for up to 1 hour.

Filtering The used hops and other solid matter are filtered out using a colander and the wort is transferred to a fermenting vessel (pic 5). The used hops are retained as they will be needed again.

Liquoring down Cold water is added to the wort to make up the volume required and to reach the correct sugar level. The latter is tested by taking small samples, cooling them quickly and using a hydrometer.

The most common method of liquoring down is known as ‘cold sparging’ – passing cold water through the colander of used hops (pic 6).

Cooling To avoid cloudiness in the form of a ‘protein haze’, the wort is cooled rapidly to near room temperature so that any proteins still in solution clump together and fall out of suspension.

Aeration Once the wort is at room temperature (about 20°C) it is aerated vigorously by being splashed about with a hand or electric whisk. This is because yeast needs oxygen for the early stages of vigorous fermentation. Do not aerate the wort while it is hot, as this may cause it to oxidise, forming the off-flavour of wet paper bag.

Pitching Yeast is added to the wort and the lid fitted to the fermenter to prevent contamination. If the lid fits so tightly as to form a perfect seal an air lock should be fitted to allow carbon dioxide to escape.

Fermentation The brew in the fermenting vessel (pic 7) should be kept at 18–25°C at all times unless otherwise stated in the recipe – lager, for example, requires a lower temperature. The wort is kept covered until fermentation has stopped, with the ‘krausen’ or brown froth sometimes skimmed off. Fermentation should take about 5 days. Once any remaining froth has sunk to the bottom of the fermenter and the air lock stops bubbling, a hydrometer is used to check the specific gravity of the liquid and determine if fermentation has ended. The specific gravity can vary from beer to beer depending on the level of unfermentable sugars.

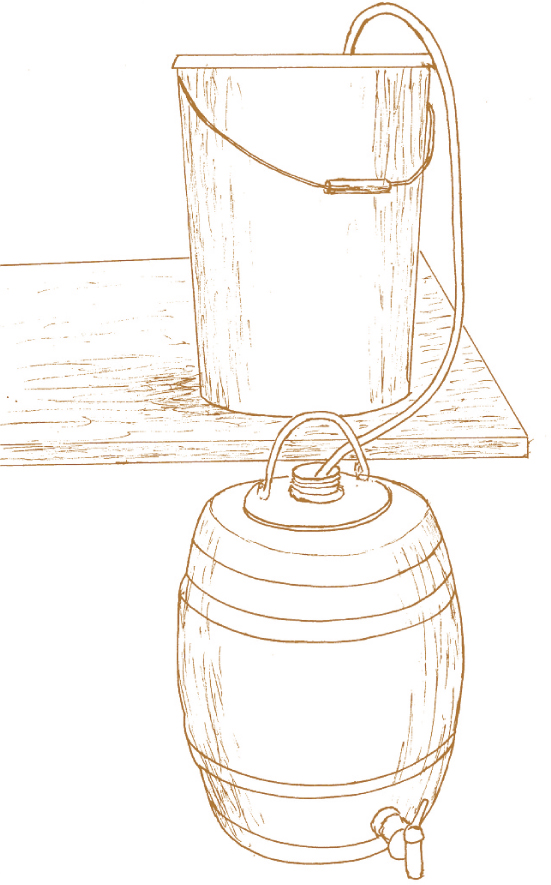

Racking and fining What could now arguably be called beer is racked (transferred using a siphon), into a second fermenting bucket if you want to bottle your beer or into a cask (pic 8) if you don’t. This separates it from the lees (dead yeast cells and other debris at the bottom), which would produce off-flavours if left in contact with the beer. Finings, which guarantee a clear beer by precipitating out particles from the liquid, can be added, though to be honest I never bother with them.

Mashing

Straining the mash

Sparging the mash

The boil

Straining out the used hops

Cold sparging the used hops

Fermentation

Racking into cask

Conditioning This is the continuation of fermentation to carbonate the beer (make it a bit fizzy). To start conditioning, a small amount of sugar is added to the beer (priming). This is added to the cask for cask-conditioned beer and to the fermenting vessel for bottle-conditioned beer, the beer being bottled as soon as fermentation becomes evident (bubbles appear). Bottle conditioning can also be achieved by adding ½ tsp sugar to each bottle before filling with the beer but if fermentation refuses to get going again you will have a flat, rather sweet beer.

Maturation The beer is ready after about 10 days for most brews, but strong beers can take much longer.

Nothing to it really. I will fill in even more details with the first recipe, which will be the model for many of the others, and, I hope, make things seem a little less daunting than they might appear at this point.

Variations on the method

There are, of course, endless variations, one of which is brewing lager (see opposite). Others include:

Parti- or split-gyling Sometimes (and I like this one) you can make two or even three different brews from the same mash; the wort that comes straight from the mash and the early part of the sparging contains high levels of sugar and can be used to make a very strong beer. The wort from later sparging will become progressively weaker and can be used to make progressively lighter beers. This technique is used by brewers; if you see Old Bastard 3.8% ABV and Complete Bastard 5.2% ABV pumps next to one another on the bar they probably came from the same mash. It is also possible to blend the different worts to get an almost infinite variation.

Adding hops at different stages Occasionally all of the hops are added at the beginning and in some cases extra hops are put into the beer when it has almost finished fermenting – ‘dry-hopping’ as it is called.

Underletting In some breweries, hot water is introduced during mashing. There are practical reasons for this, which are not relevant to home brewing, but, by increasing the temperature of the mash, underletting changes the types of sugars extracted from the malt. Because these are often unfermentable sugars, they will not be converted into alcohol and will round the flavour of the beer by sweetening it. The home-brew equivalent is to stir some hot water into the mash after half an hour or so. I have used it in a few recipes because they are adapted from professional brews, though how effective it is on a small scale is debatable.

Lager

Despite an appreciation of the finer points of ‘proper’ beers I still have an inordinate fondness for lager. People are very sniffy about this fine drink. I remember a visit to the remote North (Derbyshire) many years ago when a request for half of lager in the local pub had me down for the soft southerner that I am. To me, a good lager has a freshness seldom found in other beers, and there is nothing better on a hot day. For the home lager brewer, however, there is a problem. Lager is easy enough to make on an industrial scale but not on the small. It’s all down to temperature.

Lager-making is different in several ways from normal beer-making. Instead of pale ale malt, lager malt is used as the base malt and the hops are different, with exotic names such as Hallertau or Saaz. The most important difference is in the yeast, which is a different species called Saccharomyces pastorianus. It is a ‘bottom-fermenting’, rather than a ‘top-fermenting’ yeast, and acts more slowly, generally settling at the bottom of the fermenting vessel rather than rising with the foam.

Also, and this is critical, lager yeast ferments at lower temperatures, typically 7–15°C. It thus produces fewer of the highly flavoured esters (pear drops, fruity flavours and many more) of the top-fermenting yeasts, which work at temperatures of up to 25°C. The lack of esters provides the clean flavour (or lack of flavour!) that people like about lager. Because the temperatures in lager-brewing are necessarily lower, it takes much longer than normal beer-making. This is what gave the drink its name: ‘lager’, from the German lagern, which means ‘to store’.

It is the temperature constraints which make lager a difficult brew to master. The yeast is usually pitched into the wort when the latter is at 20°C or just below. Once the fermentation has got going – normally a few hours after pitching – the wort is moved to a cool area. The temperature should be around 10–12°C. It is left until the fermentation ceases, and then racked off into a fresh container.

Next, a ‘diacetyl rest’ is performed. The temperature is raised for a couple of days to enable the yeast to remove the diacetyl which accumulates in slow brews. Without this procedure your lager will taste of butter. For more information on this sometimes troublesome chemical, see here.

The lager is then conditioned for several weeks at a temperature of approximately 5°C. Strategically situating it in a shed during the winter will often do the trick, especially if you cover the container with blankets to prevent serious day/night swings of temperature. Realistically though, it would have to be a hard winter to maintain such a low temperature for so long. However, your lager will turn out fine provided it is reasonably cold most of the time. By far the most reliable method is to have a fridge dedicated to the task. A standard fridge has a 100-litre capacity and can usually accommodate a suitably shaped 25-litre container. At home I have a wine-cooler which lives in the loft and does the trick nicely.

A selection of commonly used malts

Ingredients

There are very few ingredients in beer but what there are come in a bewildering number of varieties, several of which may make an appearance in a single recipe. Beer recipes often look like incomprehensible shopping lists. The basic ingredients are malt, hops, finings and yeast. A few other things such as different cereals, flavourings, inorganic compounds such as gypsum and salt, and various sugars sometimes find their way into a recipe. As discussed here, malt extract may be used instead of or in addition to malt.

Malt and other grains

The list of malts available is overwhelming. If you take into account varieties and regional variations there are around five hundred. However, they do fall nicely into a dozen or so basic types and, better still, these can be divided into two general categories – base malts and speciality malts.

Base malts (usually pale ale malt or Golden Primrose, though sometimes lager malt) are the basis for most beers and it is perfectly possible to make a beer using just a base malt. They contain starch ready to be converted into sugar and the enzymes ready to do the converting.

Speciality malts may or may not have the enzymes but they will usually, though not always, have at least some starch which in one special case comes ready-converted to sugar. What speciality malts do is to provide their own particular flavours and colours but they are able to rely on the base malt to provide the enzymes which convert their starches if this is needed. Generally a beer will be made mostly with a base malt which is flavoured and coloured with a number (sometimes a large number) of speciality malts.

The different malts are made by varying the malting process, most often the drying temperature. Pale malt, for example, is dried at a relatively low temperature, preserving the enzymes and not toasting it. Amber, brown, chocolate and black are progressively darker malts subjected to progressively higher temperatures. Black malt looks (and tastes) like the stuff you scrape off toast before you can eat it.

Crystal malt, which comes in a variety of shades and sugar profiles, is unusual in that most of the starch has already been converted to sugar, as it is wetted after drying and then dried again when the enzymes have done their job. If the malt is re-dried at a high temperature some of the sugars caramelise and become unfermentable and so retain their sweetness in the finished beer.

Acid malt is an interesting malt, as the lactic acid tang it provides is useful in the making of lager.

If you see the mysterious symbol L° on the label it simply refers to the colour where, for example, 2L° results in a pale ale or lager and 35L° in a stout. The ‘L’ is a reference to one of the brothers Lovibond who came up with this bright idea; 35L° would therefore be rendered as ‘thirty-five degrees Lovibond’.

Other grains Barley is not the only cereal used to make beer. Unmalted wheat, corn, oats and other grains are often added to beers for their special qualities, such as removing protein hazes, reducing tannin levels, improving the head and adding flavours in the form of esters for hints of banana and cloves. The starches in these grains are converted to sugar by the action of the enzymes in malted barley.

Wheat and oats can be malted to make wheat and oat beers, though a base barley malt is usually used to maintain sugar levels and provide extra enzymes.

The point of describing all this is to reassure you that the large number of malts and other cereals called for in some recipes is actually needed; the various malts are very different and they can make very different beers.

Malt extracts

Malt extracts are used instead of or in addition to malts in beer-making. They are the basis of extract brewing, removing the necessity to extract the sugars, colour and flavours from malt grains yourself. All the extraction work has been carried out in a factory and the malt extract supplied in tins or packets ready for use.

They come in a variety of colours (very pale, pale, dark, and so on) and produce different coloured beers. Malt extracts all have individual sugar profiles with varying amounts of unfermentable sugars, which can affect the finished sweetness and body of a beer. These are not usually referenced on the packaging but the information can be obtained from the supplier. Malt extracts can also be used in wholegrain brews to increase the original gravity.

Specific gravity

The amount of malt or malt extract used to make a given volume of beer is the chief determinant of the original gravity (OG) of the beer, the specific gravity just before fermentation is started. Once fermentation is complete the beer will have a final gravity (FG). Using the simple formula (OG—FG) x 0.13 it is easy to roughly calculate the percentage alcohol content of the beer, as the difference between the two gravities indicates how much sugar has been converted to alcohol. With an original gravity of 1042 and a final gravity of 1007, for example, you will have a 4.5% ABV beer. Beers are often spoken of as being high, medium or low gravity, references to their original gravities and likely alcohol content.

Beers with a final gravity above 1010 tend to taste sweet; below this, even though sugars are present, they are barely detectable. Beer never reaches the low final gravity of wine (1000 or less), as it contains high levels of unfermentable sugars.

Malt extract

Hops

Hops

Hops are, relatively speaking, a new invention. Before the arrival of hops, ale was flavoured and preserved with a variety of unlikely herbs. However, the hop’s ability to keep ale fresh – and, quite frankly, give it a vastly improved flavour compared to what went before – soon made it a near essential ingredient in ale. Thus it was that ale became beer. But not everyone was pleased. Henry VIII took particular exception to hops and banned them. A long and tedious poem of 1661 by one ‘Antidote’ and not very wittily entitled The Ex-Ale-tation of Ale praises ale in every verse while attacking beer and hops and taking side swipes at Calvinism on the way.

And in very deed, the hop’s but a weed

Brought over against the law, and here set to sale,

Would the law were renew’ d, and no more beer brew’ d,

But all men betake them a pot of good ale.

The hop genus, Humulus, has only three members, of which Humulus lupulus, the common hop, is by far the most important. The nearest genus to Humulus is Cannabis, an unsurprising fact if you are familiar with both plants. Indeed the resin that collected on the knives of Kentish hop-pickers was once used as an invigorating addition to tobacco, showing that the plants share more than an ancestor. But such dark thoughts must be put aside; we are only interested in the benign qualities that hops give to beer. If you have never smelled a handful of dried hops you are in for a treat. They are aromatic, heady and crying out to be included in perfumes as a guaranteed attractant to warm-blooded males. They are, after all, flowers.

Three characteristics are supplied by hops: bitterness, complex aromas/flavours and preservatives.

A list of available hops is as long as a list of available malts, making endless permutations possible. Many are grown in Britain – Fuggles and Goldings being the best known – but many more are grown abroad and imported. With hops you often have to give up the idea of food miles, because many recipes call for hops from distant lands. Of course if you want to stick to domestic hops you can; it just slightly restricts the type of beers you can produce.

Hops are almost always used in dried form, sometimes in vacuum-sealed packets, sometimes just in a bag, and occasionally as pellets. They deteriorate quite quickly so if you have some left over, keep them in the freezer.

It is possible to use completely wild hops in your beer, though the flavour will be quite random and they do not provide a great deal of bitterness. However, if you do find some, they can be used in a once-a-year brew that is much looked forward to in many hop-growing areas. Although I have never used the wild hop flowers for beer, I collect young hop shoots in the spring. They are rather good in a stir-fry or an omelette.

Bittering hops The bitterness in a beer comes from alpha acids in the hops that are added at the beginning of the boil – the bittering hops (see here). Such hops do not need to be particularly fragrant, because any fragrance would be lost during boiling anyway. The alpha acids, which are present in surprisingly large – if variable – quantities in hops, are, unhelpfully, insoluble in water. The boiling process, however, turns them into soluble ‘isomers’. If you are interested, an isomer of a compound is a rearrangement of its constituent atoms in a new shape: in this case the boiling reorders the molecular structure of the alpha acids into molecules that are soluble in water. It takes around 45 minutes for the isomers to be created. Boiling for a shorter length of time just wastes alpha acids as they will not become soluble and a longer boil will only slightly increase the bitterness.

If you look at a catalogue of hops you will find a description of each hop that includes the bitterness that can be expected from it. This is expressed as the percentage of alpha acids, which can range from 3% to nearly 20%. The final bitterness of a beer depends on four things – the quantity of hops used, the percentage of alpha acids in the hops, the boil-time and the original gravity (the level of sugar in the wort).

The higher the original gravity, the less bitter the beer will be because sugar reduces the solubility of the alpha acids. In short, strong beers need more alpha acids than weak beers to reach the same level of bitterness. The technical term for this is ‘hop utilisation’.

The final bitterness of a beer is expressed in IBUs (International Bitterness Units). If you think all this is complicated then I tend to agree with you. However, you only need to worry about such matters if you are inventing your own recipes and all the recipes here have been invented (and tried!) already.

Finishing hops If the bitterness of hops and the sometimes toasty qualities of malts were the only flavours in beer it would be a dull drink. Many of the fine aromas and flavours we expect come, unsurprisingly, from aroma hops. They are also known as ‘finishing hops’ as they ‘finish’ the beer.

Although some hops have both good bittering qualities and good aroma qualities, there are many specialised finishing hops that contain small quantities of highly aromatic essential oils. These are very volatile and would be lost if added at the beginning of a long boil so they are added towards the end. Just 15 minutes before ‘heat off’ is typical, with more added 10 minutes later, though this can vary from recipe to recipe. Sometimes the hops are added just as the wort comes off the heat, ‘at knockout’, and sometimes they are added to the cask after fermentation has more or less ceased – ‘dry-hopping’.

Each one of these methods will produce different flavours, as each has a different effect on the amount of essential oils that are released and then retained.

Brewers hate to waste anything so it is common practice to ‘cold sparge’ the hops and other solid matter that was filtered out earlier with cold water, running it into the wort (see here). This extracts the last bit of flavour from the hops and also rescues a considerable amount of wort.

Yeast

Although most of the yeasts used in brewing are Saccharomyces cerevisiae, brewer’s or baker’s yeast, this species comes in a large number of varieties. Their primary task is to convert water and sugars into alcohol, but they are also responsible for many of the subtler flavours found in beers. As with malts and hops, each variety of yeast produces its own characteristic flavour – though some are more neutral.

Different yeast strains also act differently during the fermentation process. They may possess talents, such as the ability to sink conveniently to the bottom of the fermenter once they have finished their work, or tolerate low temperatures or high alcohol levels.

For us home brewers, yeast is most likely obtained in dried form in little packets sufficient, usually, for a 25-litre batch. You can also buy them in impressive little test tubes, though these are usually the more specialist home-brew yeasts which come with fancy names such as ‘Brew Lab 2000 Somerset 1’.

As with wine-making, wild yeasts floating around in the air sometimes get into a brew; in fact some beers, called ‘lambic beers’, rely entirely on wild yeasts. Lambic beers are a little worrying because, while they often work out well with some unusual but pleasant flavours, sometimes they don’t, and 25 litres is a lot of beer to empty down the drain.

Flavourings

Although hops, malt and the activity of yeast produce most of the flavour of beer there is no real reason why you cannot add any flavour that takes your fancy. Most flavourings are added towards the end of the boil to ensure that they have time to find their way into the wort, but not so much time that the flavours boil away.

The recipe here uses orange as a flavouring and most other fruits will have an interesting effect on the taste of the finished beer; one must simply be confident that it is a pleasant effect too. Traditional ale flavourings such as burdock or sweet gale can also be used to give a taste of ancient brews, and I have included recipes that do just that here and here.

Commercial breweries sometimes add unusual ingredients towards the end of fermentation as I discovered on a visit to the St Austell Brewery in Cornwall, where I saw a huddle of brewers frantically cutting off the green bits from 500 kilos of strawberries for a special strawberry-finished lager. They sent me a few bottles later and the effort seemed entirely worthwhile.

Finings

One utilitarian addition to a wort or beer is finings. These natural materials clarify the beer by collecting the cloudy particles and precipitating them to the bottom of the fermenter. They come in two varieties: copper finings and beer finings.

Copper finings A favourite copper fining is the common seaweed carragheen. This is something I collect and dry myself and I like the idea that I have foraged at least a tiny part of my beer. Carragheen is easy to find on rocky shores but also easy to buy if you are not near the seaside. Carragheen is a copper fining because it is put in the boiling pot, traditionally called the ‘copper’, not because it is some nasty compound of copper. It is also available in tablet form under the name Protofloc.

Beer finings Copper finings only help precipitate out the proteins; to clear the beer of dead yeast, beer finings can be added to the fermented beer prior to conditioning. Strangely, many of these too have a maritime origin, being made from boiled crustaceans. You can usually get away without using beer finings because most beers clear with time, and many real-ale fans consider the obsession with crystal-clear beers to be a passing fad. Certainly they are not needed in dark beers.

Sugar

The most important use of sugar in brewing is to extend the fermentation process once the main flush of yeast activity has passed. This extra sugar (usually plain sucrose) is added to the bottles, fermenter or cask to condition the beer. The yeast will release a predictable amount of carbon dioxide, giving the beer a bit of fizz and head. Adding sugar in this way is called priming.

Sugar is also occasionally added to a boil with the sole intention of making the beer a little stronger without using extra malt which might make the flavour too heavy because of its distinctive taste and unfermentable sugars. Invert sugar – a mixture of glucose and fructose derived from the more complex sucrose – is often used, as is glucose (sometimes referred to as ‘brewing sugar’) alone.

Seemingly contrary to this, sugar can be added during the boil to sweeten a beer, giving it more body. There would be no point in using ordinary white sugar for this as it would be consumed by the yeast, but many dark sugars contain unfermentable sugars that the yeast cannot devour. Very dark raw sugars and caramel contain sufficient quantities of these to sweeten a beer with the bonus of adding colour.

Brewing salts

Various inorganic compounds such as gypsum, bicarbonate of soda and calcium carbonate are often added during the boil to adjust the pH of the water used and to improve the ‘mouth-feel’ of the finished beer.

Dried carragheen

My 72-litre copper

Equipment

If you wish to use the traditional method of wholegrain brewing that I champion, you do need a lot of ‘kit’, and big kit at that. With wine you are dealing with just a gallon or maybe two, but home-brewed beer can only sensibly be made in 25-litre (5-gallon) batches. I do, however, make many test batches of only 10 litres, and if you want to make beer on this very small scale you will find that the equipment is much more manageable. All of the items below can be obtained from home-brew suppliers. Malt-extract brewing calls for fewer fermenting buckets and you will not require a mash bag. All the equipment assumes a batch size of around 25 litres.

Copper For the domestic situation only a stockpot will be large enough for this job. It must be capable of holding at least 30 litres of liquid and come with a lid. I always like my kit big, but slightly regret buying the 72-litre stainless steel monster that now lives in the garden because it will not fit in the shed, let alone the kitchen.

A copper is also used to heat the water for the mash and the water for sparging. You will, of course, need a hob to heat it up on.

Thermometer This is absolutely essential in beer-making, as the brewing process is very temperature-sensitive. A plain glass thermometer is best.

Weighing scales These need to be capable of accurately weighing anything from 10 kilos (malts) to just a few grams (hops and other light ingredients).

2-litre plastic measuring jug You will need a jug to pour water for sparging and for other tasks.

Long-handled plastic spoon Used to stir the mash and the boil. A plastic spoon is easier to keep sterile than a wooden spoon.

Fermenting buckets Although called fermenting buckets, these are used for all sorts of things. They are made of food-grade plastic. Two of the buckets require some very low-tech modifications and they all need lids. The following list may seem like a lot of buckets but it does make things much easier:

•A 25-litre bucket in which to make your mash (although it is possible to use a smaller bucket for small mashes).

•A graduated bucket with a capacity greater than 25 litres to collect the wort. Now 25-litre fermenting buckets are often slightly larger than 25 litres, whatever they may call themselves, and this is the sort that you need. Most have volume markings on the side and if there seem to be 2 or 3 litres beyond the 25-litre mark that is the bucket for you. Failing this, a 33-litre bucket will be fine. Whichever size you use the lid must be flat (not domed in any way). Cut a circular hole in the lid, which leaves about 4cm of polythene around the inside of the rim. This is so that you can sit the next bucket to be described on top and allow the wort to flow through.

•A 25-litre bucket identical to the previous bucket. This one holds the grains while they are being sparged. You will need to drill about forty 3mm holes in the bottom as it is going to act as a very large sieve into which the mash is poured from the mash bucket.

•A 33-litre bucket for fermentation. The extra 8 litres are to accommodate the froth that rises to the top of a brew. The lid should have a single hole in it to accommodate a rubber grommet for an air lock.

Top: Beer fermenting vessels

Bottom: The modified fermenting vessels

Mash bag This is a large nylon bag which is used to contain the mashed malted barley inside the poor fermenting bucket that has the holes drilled in it.

Colander Sieving out the hops and other solid matter is best achieved with a deep colander lined with muslin.

Muslin cloth Used to line the colander (above) and to make ‘hop bags’ for dry-hopping. The bag of hops is tied with string, leaving a long piece to suspend the bag in the cask or fermenter. When the lid is screwed on it will stay in place.

Cooling equipment The wort needs to be cooled rapidly after the boil and some method must be devised for doing this. Acquiring new kit is, however, optional because you can simply stand the fermenting bucket, full of hot wort, in a large sink of cold water and throw in some ice. My preferred method involves a large flexible builder’s bucket partially filled with water and, again, ice.

A much more efficient, sophisticated and downright complicated approach is to buy some 10mm copper pipe and some fittings and make a helix that fits into your 33-litre fermenting bucket – a ‘cooling coil’. Using a hosepipe, cold tap water is run through the helix until the temperature of the wort is reduced. I will leave the fine details of this up to you.

Whisk An electric or hand whisk is used to aerate the wort.

Siphon tubes These come as simple flexible plastic tubes which can be adorned with rigid plastic tubes, a little device on one end to preventing sucking up the lees, or with clips to attach it to a fermenting bucket. You can also buy self-priming siphons which save a great deal of sucking and mess.

Hydrometer An essential item, this measures the specific gravity of a brew. Calibrated to work at 20°C, a hydrometer will give a misleading reading if used at higher or lower temperatures. A small quantity of wort or beer should be transferred to a trial glass and cooled before testing. For more on hydrometers, see here.

Trial glass To hold a sample of beer or wort for testing with a hydrometer.

Heating equipment Maintaining a steady temperature for your brew can be very difficult. The ideal temperature for most fermentations is 20°C, or up to 25°C for a fruity beer, and it is best if the temperature is kept at the same level. If you have a room that maintains this temperature day and night it will be fine. Otherwise buy a flexible builder’s bucket large enough for your 33-litre fermenting bucket to fit inside and a thermostatically controlled 150-watt waterproof aquarium heater. The fermenting bucket is placed inside and water poured around it until it just starts to float. Suspend or otherwise fix the heater, set to 20°C, in the water at about the halfway mark and plug it into the mains.

Incidentally, with 25-litre batches it is seldom necessary to cool your beer, though the heat of fermentation itself can require cooling in commercial breweries. If your brew threatens to go beyond 25°C, drape wet towels over the fermenting bucket. This Heath Robinson arrangement works very well but is a bit messy.

Barrels or casks These come in 10- and 25-litre sizes. They are fitted with a tap and a screw top with a very simple pressure valve in the middle. In fact it is just a collar around a small spigot with a hole in the side. It will maintain a pressure just a little above atmospheric. I prefer to keep my beer in cask (the effort of removing bottle caps has become too much for me) and I have accumulated a large and proud collection.

If you want to bottle your beer you can keep it in a cask to settle and mature first or you can use the fermenting vessel below.

25-litre wide-neck fermenting vessel A 25-litre wide-neck fermenting vessel is useful if you wish to bottle your beer. Some come with a tap fitted – or you can fit one yourself. Although it is possible to bottle beer using a siphon it is tricky and inevitably messy; a tap makes things much easier, especially when fitted with a bottle-filling attachment.

Bottle-filling attachment This is a tube, long enough to reach the bottom of a beer bottle; on the end is a valve so that when you take the bottle away the flow will stop. I love these things as they take the stress out of bottling and prevent most of the sticky floor problem that has caused so much domestic exchange over the years.

Beer bottles These can be bought new but it is an ideal opportunity to recycle. Beer bottles are easily obtainable from pubs, because breweries seldom want their bottles back these days. For advice on how to deal with recycled bottles, see here. Alternatively, you can buy swing-top bottles.

Bottle or ‘crown’ caps These come in a range of colours, presumably so you can colour-code your beer collection. They come in bags of one hundred.

Crown capper There are several gadgets designed to fit crown caps to beer bottles. I use a simple hand-held device, which must be hit nerve-wrackingly hard with a hammer. A bench-mounted capper is a more sedate option, though more expensive.

Carbonator This is optional but I would never be without one. It is a sad fact that as you draw beer from a cask the amount of beer left in the cask is reduced. This is hard enough to bear, but after a pint or two the pressure of the carbon dioxide in the cask (which was produced by the conditioning process) is also reduced and the beer no longer flows unless you allow air in by loosening the screw top. Oxygen and beer do not make happy companions and the beer can quickly go sour. Letting air in can also introduce micro-organisms which will also make the beer sour.

A simple, cheap solution to these problems is to fit a carbon dioxide cylinder to the barrel, replacing the plain plastic screw cap with a valved plastic screw cap that will receive a carbon dioxide cylinder. Once the gas is turned on, the headspace is then filled with carbon dioxide, pressure is restored and the beer will flow again. This is not quite the same as adding carbon dioxide to a beer – that would need a great deal more kit and carbon dioxide than can easily be provided at home. But the beer comes out with a good, or at least big, head and you can taste the extra fizz.

Two simple arrangements are possible – disposable carbon dioxide bulbs and reusable carbon dioxide cylinders. Fitting either of these is scary the first time you try it because there is a great deal of fizzing and the cask inflates as though it is about to take out both you and the kitchen. Do read the instructions on the side of the reusable cylinders; take the advice on only giving one-second bursts seriously.

If you want to impress absolutely everyone however, a pressure-regulated system complete with dials, valves and pipes is available to buy surprisingly cheaply.

None of the above items of equipment are hard to obtain or particularly expensive.

Cleanliness

It is worth mentioning that half of the disasters that beset the early days of my beer-making career were due to inattention to timings or attempting to ferment at the wrong temperature, and the other half to a lack of scrupulous cleanliness.

You do not need to worry about your equipment being sterile until the moment you turn the wort off the boil – you could use a stockpot with traces of last week’s vegetable stew in it or throw in old socks; it would not affect the brewing process at all, though it would not help the flavour particularly. But as soon as the gas goes out you must be very careful; everything that the wort or beer touches after that must be sterile. The cleaning process is described here.

The wort should always be kept covered in the fermenting vessel until it is ready to bottle or keg, though you are allowed to take an occasional peek and sniff to check everything is going to plan. You have already aerated your wort so exposing it to further air will not help and may introduce unwanted livestock such as fruit flies. Once fermentation has ceased the beer should be handled carefully and not splashed around too much as this will introduce oxygen when it is not wanted.

Keeping records

Record-keeping is a major part of brewing and some of the old record books kept by ancient brewers make fascinating reading. For example they often give the weather on brew days going back centuries – a resource for historical climate data buffs. You do not need to note that it is a fine sunny day but it is really important to record everything else. The recipe itselfmust be recorded or referenced of course, along with timings, specific gravities, temperatures and pH if you have a meter. You should also keep comprehensive records of the appearance and taste of your brew at strategic moments in its life.

Such records help enormously if things go wrong and enable you to tweak the recipe or your method if you think of possible improvements. While most people are happy to produce elderberry wine without resorting to pen and paper, beer-making is sufficiently complicated to merit extremely careful records.

Things that go wrong with beer

There are a lot of these – but I expect you guessed that already. However, you should not run into any problems provided you stick to the correct temperatures and timings, and keep everything covered and very, very clean.

Contamination by malicious bugs is the cause of most beer disasters. This is a good thing because cleanliness is actually very easy to maintain, and such problems are correspondingly easy to avoid. See here for my cleaning recommendations.

If there does not appear to be anything much wrong with your beer apart from the fact that it doesn’t taste very nice I advise you to give it time. We seldom expect wines to be drinkable within a week or two and this can apply to beers as well. I have lost track of the number of occasions I have found a beer to be disappointing only to revisit it 3 months later to discover it has matured to glory. So be patient, and do not consign a brew to the sink until all hope is lost.

Assuming you avoid all or most of the problems associated with bacterial or fungal contamination, what other disasters lie in wait?

Buttery taste to the beer

This extraordinary ‘problem’ is down to a chemical called diacetyl which makes things taste buttery. You take a sip of beer, everything seems to be fine, then your mouth fills with the taste of butter. In small quantities it improves the flavour of many beers, giving them a rounder taste. But in some it is a disaster; lager makers in particular go to great lengths to remove as much diacetyl as possible.

Diacetyl is a natural product of the brewing process and it’s quite likely that the buttery flavour will become pronounced at some point during beer-making. Fortunately it is absorbed by live yeast and is likely to disappear altogether without any intervention.

Incomplete fermentation, however, often results in excess diacetyl so the following steps are particularly important in bringing the levels down:

•Ensure there has been adequate aeration before adding the yeast.

•Pitch enough yeast to give your brew a good start.

•Do not shock the beer with wildly varying temperatures during fermentation.

•Low fermentation temperatures can raise diacetyl levels, so keep to the suggested temperature.

•Ensure good hygiene to avoid infection, which can also result in diacetyl.

If you still find that your beer is too buttery (usually this will be evident when you rack it) then raise the temperature a little to stimulate the yeast for 2 or 3 days. This is called a ‘diacetyl rest’ and it is standard practice in many breweries. This rest can sometimes be encouraged by adding 2 tbsp sugar to keep the yeast active; it may even help to add some high-powered ‘restarter yeast’ to get things going.

Do not worry too much – several times I have thought of chucking a batch of beer down the sink only to find that a week later it tasted just fine. There was evidently enough yeast activity to remove the diacetyl.

Off-flavours

The most common cause of off-flavour is autolysis, the breakdown of the dead yeast cells that accumulate in the bottom of your fermenter. Once it starts it can quickly ensure that your beer tastes of wet dog or cheese long past its sell-by date. Fortunately it takes a fair amount of neglect for this unpleasantness to occur, and racking off a day or two later than anticipated is unlikely to cause any problems.

There are many other off-flavours available to the careless or unlucky brewer, most of which are down to poor hygiene or, at least, very bad luck – a vinegar fly diving into your fermenting bucket during the few seconds it is uncovered, for example. Overheating the wort during fermentation and exposing the wort or finished beer to sunlight can also produce unpleasant flavours and aromas. The answer to the last two is don’t.

Stuck fermentation

I hate this. Such joyous hopes travel with our brews and to see them sulking on Tuesday when they seemed so happy on Monday feels like a betrayal. Prevention really is better than cure here. If your fermentation is stuck then something was not right from the beginning.

If your beer does not ferment at all (no bubbles, no smell of carbon dioxide, nothing) then there is probably something wrong with your yeast and you should re-pitch with fresh yeast. This is a very rare occurrence and I cannot remember the last time I encountered a bad yeast.

If the fermenting temperature is correct and you aerated your wort thoroughly then a stuck fermentation is unlikely. The first step is to check if you really do have a stuck fermentation – it may be just a completed fermentation. Test the specific gravity, and if it is much higher than the final gravity that you are anticipating then the fermentation is indeed stuck.

Once you’ve established that you have a stuck fermentation check the temperature. If it is not correct then move the fermenter to a more salubrious environment. It is worth stirring the wort to swirl any live yeast that may have settled to the bottom back to the top where it will do some good. Adding a fresh batch of yeast may also help. Special ‘restarter’ yeasts, which can tolerate being introduced to a partially brewed beer, are available. There’s even a type of yeast selected for use at the priming stage – when stuck fermentation is particularly common, resulting in a flat beer.

Most yeasts can be sprinkled on, but if this fails, then mix a little warm water with 1 tsp sugar and the yeast in a jug. Cover and leave until fermentation is well under way then add about 50ml of the stuck beer. Wait until this starts fermenting then add another 100ml beer. Once this is fizzing away merrily pour it back into the fermenter and keep your fingers crossed. If all is well you should see signs of fermentation within an hour or two.

Simple model brew:

Orange pale ale

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1040–1042 | 4.3–4.5% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1007 |

This is among the simplest wholegrain beers I know and it is very reliable. The brewing process itself is as straightforward as things can be in a wholegrain brew. If you are new to beer-making I strongly suggest you try this brew first, or at least read the recipe carefully as it gives an essential introduction to the basic process of wholegrain brewing. I have divided the stages to make what will still seem like a horribly complicated process a little less forbidding.

Each of the subsequent brews will follow, more or less, the same basic process. Temperatures, quantities, timings, ingredients and occasionally parts of the method will vary, but once you know how to make this brew you will understand how to make the rest. Even malt-extract brewing follows the same process except that it leaves out the first two steps, replacing them with the adding of malt extract at the start of the boil.

Orange beer is one of the three beers that I do not like to find myself without, so I make a batch every few months. It uses only a base malt – English pale ale malt – and a single hop – East Kent Golding, an all-round hop which is mildly bittering (4–5.5% alpha acids) and has flowery finishing qualities. The finished beer is very light with a nice top note from the orange peel. The orange can be left out if desired and other flavourings added – two (gloved) handfuls of nettles will give you a nettle finished beer, a sliced 3–5cm piece of ginger root will give you a ginger beer, and so on. Among the best of the variations is spruce beer. Gather the young, pale green tips in spring and early summer and add a small handful instead of the orange peel.

As with all beers, temperatures are critical, so do keep to them as closely as you can. There is a great deal of logistical manoeuvring with liquids being poured from one container to another so keep calm. As this is a model brew I will go through all the stages in detail. This and all the other beer recipes are for about 25 litres.

The specific gravities you actually get may vary from those provided – it all depends on how efficient your mashing and sparging are. Don’t worry about this unless it is a long way out. If it is more than three or four points too low then either add some malt extract before the boil or, since the wort becomes a little more concentrated during the boil, you can make a little less beer instead. In this case miss out or reduce the liquoring down. The only potential issue with this is that if you are leaving it in the cask it will have an air gap at the top, though since this is usually filled with carbon dioxide it is seldom a problem. If your specific gravity is too high then you will just get a stronger and sweeter (full-bodied) beer.

Makes about 25 litres

4kg pale ale malt

30g East Kent Golding hops

200g brown sugar

Zest of 1 unwaxed orange

2 tsp dried carragheen

11g sachet ale yeast

1 tsp beer finings

50g sugar for priming

Mashing Place the malt into a fermenting bucket. Your humble fermenting bucket has now been promoted to a ‘mash tun’. It is important to make sure that the malt is at about room temperature before you begin the mash. Heat 13 litres water in your copper to 76°C. Pour and stir the hot water into the malt to make your mash, which should end up at close to 66°C; this temperature is called the ‘mash heat’. You can safely tweak it by stirring in hot or cold water. Fit the lid. The temperature should be maintained for 1¼ hours, so stand the fermenting bucket on something insulating and cover closely with blankets or a duvet.

Sparging While your mash tun is doing its bit, heat about 17 litres water to 78°C in your stockpot. It will need to be kept at this temperature throughout this process, which calls for constant checking with thermometers and adjusting hob knobs.

Now a bit of kit preparation. Fit the lid with the very large hole cut out of the centre onto the 25-litre fermenting bucket without holes in the bottom. Stand the fermenting bucket with the holes in the bottom on top of the other bucket, with its bottom resting on the lid. Drape the mash bag inside the top bucket and tie in place with the string provided. It is worth putting the handle of a teaspoon between the bottom of the top bucket and the lid of the bottom bucket to release air, which can force the wort all over the floor.

When the mash is ready, carefully pour all of it into the top bucket. The wort will run through to the bottom bucket. Wait until most of it has gone through then use a plastic jug to carefully pour 2 or 3 litres hot water over the surface of the malt until it floods a little. Wait until the wort almost stops running out of the bottom then sprinkle on another 2 or 3 litres water. Continue until you have almost 25 litres wort in the bottom bucket. About another 1 litre wort is available to make up the 25 litres by lifting and gently squeezing the mash bag. Do take your time with the whole sparging process – at least an hour – so that as much of the sugar is collected as possible. You can, if you want, use the practice of slowly sprinkling the hot water onto the mash but it is boring and will not produce better results. The grains are no longer required for your brew (but chickens love them).

It is well worth testing the wort with a hydrometer at this point. The specific gravity of a cooled sample at this stage should be about 1041. What do you do if it isn’t? A higher specific gravity does not matter but if it is below 1036 stir in some pale malt extract, 50g at a time, until 1041 is reached. You may like to drink a little of your wort at this point; it tastes like watery Horlicks.

The boil Pour the wort into your copper. I suggest using your plastic jug to transfer at least half of it as a 25-litre bucket full of hot wort is a little unwieldy. Bring the wort to the boil and add 10g of the hops and all of the brown sugar; this is called adding ingredients at ‘copper-up’ – the moment when the wort comes to the boil.

Boil the wort gently for a total of 1¼ hours with the lid on, adding another 10g hops, the orange zest and carragheen after 1 hour, and stirring in the third and final 10g hops after 1 hour and 10 minutes.

Standing Turn off the heat and leave the copper to stand for 40 minutes. From this point onward everything that touches the wort or beer needs to be sterile.

Filtering Pour the wort into the 33-litre fermenting vessel through your muslin-lined colander. Stand the colander of soggy hops in a clean bowl for use later.

Liquoring down Add cold tap water (most tap water will be near enough to being sterile) to the wort by passing it through the colander full of used hops (cold-sparging), until a specific gravity of about 1040–1042 is reached. This is the original gravity. The cold sparging returns some sugars and flavours to the wort. If you checked and perhaps adjusted the specific gravity at the end of the sparge there should be about 25–26 litres. Do not worry unless it’s wildly out; once, when it was I got away with addingmalt extract at this point to give the correct SG and volume.

Cooling Cool rapidly by standing the bucket in a sink or flexible builder’s bucket full of water and then adding ice to the water, or use a cooling coil (see here). Leave it to cool to about 20°C.

Pitching the yeast Aerate the wort by whisking or stirring with a large whisk to ensure that it has enough oxygen to allow your yeast to grow. Pitch the yeast and cover with a lid that has an air lock fitted. Keep at 18–25°C (20°C is ideal), checking to make sure a nice foam has formed after a day. After about 5 days this foam will sink to the bottom as the fermentation slows or stops. Check the specific gravity at this point; it should be about 1007.

Racking The beer needs time to mature and clear, and also needs to be removed from the layer of dead yeast at the bottom of the fermenting vessel. If it is not then autolysis (decomposition of the dead yeast) can occur and produce off-flavours.

Separating the beer from the lees is done by ‘racking off’ into a cask or wide-neck fermenting vessel using a siphon. Do not splash the beer to allow in oxygen.

Finings Stir in the finings after 3–4 days, using your long-handled spoon. This is strictly optional as the beer will likely clear anyway.

Conditioning and storing After 7–10 days, prime the beer by stirring 50g sugar into the cask for ‘cask-conditioned’ or into the fermenter for ‘bottle-conditioned’. It is worth leaving the sugar for a day or so in the fermenter before bottling to see if fermentation has started again (you should see bubbles rise from the surface of the beer). If it sits and does nothing for 2 days, restart the fermentation as for a stuck fermentation by making a restarter batch as described here. The sugar does not have to be added to the fermenter; instead you can place ½ tsp in each bottle before adding the beer, but it is impossible to fix things if refermentation refuses to start.

The beer is ready to drink after 2 weeks. In bottle-conditioned beers you will find a sediment forms at the bottom of the bottle; this is as it should be – just pour carefully. Sediment will also form in the bottom of a barrel but, being below the tap, is usually no trouble.

Orange pale ale

Ordinary bitter

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1039 | 4.2% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1007 |

If whisky is the national drink of Scotland then bitter must be the national drink of England. No pub will be without a bitter and many boast several from a number of different brewers. Apart from the brewer’s name on the pump they are identified as ‘ordinary’, ‘best’ and ‘special’, reflecting their alcohol content. ‘Ordinary’ will be around 4%, ‘best’ around 4.5% and ‘special’ anything stronger. I have called this ‘ordinary’ only in this technical sense; it is one of the best bitters I have tried.

It could be argued that ‘bitter’ does not actually taste all that bitter. The term was invented by pub clientele to distinguish it from mild ale, which was, well, mild; the brewers just used to call it light bitter ale, or pale ale, if it was stronger. This bitter contains some wheat malt, which improves the ‘head’ and ‘mouth-feel’.

Makes about 25 litres

4.5kg pale malt

200g wheat malt

350g crystal malt

50g chocolate malt

25g Pacific Gem hops

2 tsp dried carragheen

25g East Kent Golding hops

11g sachet ale yeast

1 tsp beer finings

50g sugar for priming

Place the malts in a fermenting bucket, mix well and stir in 14 litres water at 75°C. The mash heat should be 65°C. Cover and keep it warm for 1¼ hours.

Sparge as normal with water at 78°C until you have 25 litres wort.

Pour the wort into your copper and boil for a total of 1½ hours, adding the Pacific Gemhops at copper-up and the carragheen and East KentGolding hops 15 minutes from the end. Allow to stand for 40 minutes.

Transfer to your fermenting bucket, straining out the used hops, liquor down until the specific gravity is at 1039, then cool rapidly.

Aerate and pitch the yeast at 20°C. Leave to ferment for about 5 days until fermentation is complete and the specific gravity is about 1007.

Rack, fine and prime as usual, depending on whether the brew is to be bottled or left in cask. Most bitters are left in cask so I should stick with tradition.

Special bitter ale

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1051 | 5.2% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1012 |

Back in 1902, S.W. Arnold of Taunton made a Special Bitter Ale using Oregon hops. To make a beer which is similarly spicy and fruity, I am using Bramling Cross hops which, although English, have the flavour of the old American hop. The original recipe also calls for both Chilean and Smyrna pale malt, food miles evidently not being much of a concern back then; I’mbringing these ingredients closer to home too.

Makes about 25 litres

2.2kg English pale ale malt

2.2kg Scottish Golden Promise malt

500g flaked maize

4 tsp gypsum

75g East Kent Golding hops

200g Mauritian light brown sugar

200 g invert sugar

2 tsp salt

2 tsp dried carragheen

45g Bramling Cross hops

11g sachet English ale yeast

1 tsp beer finings

50g sugar for priming

Put the malts and maize into a fermenting bucket. Heat 14 litres water to 74°C, add half the gypsum, then stir into the malts and maize. The mash heat should be 67°C. Cover and keep warm for 1¼ hours.

Sparge with water at 78°C until you have 25 litres wort.

Pour the wort into your copper. Boil for a total of 1 hour 50 minutes, adding 30g of the East Kent Golding hops, the brown and invert sugar, the salt and the rest of the gypsum at copper-up. The carragheen is added at 1½ hours and the Bramling Cross hops 10 minutes later. Leave to stand for half an hour, then strain into a fermenter.

Liquor down until you have a specific gravity of 1051. Cool rapidly.

Aerate and pitch the yeast when the wort is at around 20°C. Leave to ferment for about 5 days until fermentation is complete and the specific gravity is about 1012.

Rack into a barrel or wide-neck fermenter and add the rest of the East Kent Golding hops tied in a muslin bag. Rumble the barrel or fermenter every day for a week or two to distribute the hop flavour around the beer.

After 2 weeks it may be fined and primed in the barrel or bottled in the usual way.

Special bitter ale

Alastair’s session bitter

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1038 | 3.8% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1011 |

I know few people who talk as much as my friend Alastair and none who talk so much about beer. He devised this award-winning beer for his old brewery in Wiltshire and it’s one of his favourites. Even people who do not really like beer tell me they love its lightness and hoppy flavour and I have to tell them to stop drinking mine and make their own. A ‘session bitter’ is any beer between 3 and 4% ABV which has a good balance of hops and bitterness and no particularly strong flavours that might become tiresome after more than five pints. In other words, one that’s good for a ‘session’.

Makes about 25 litres

3.5kg English pale ale malt

75g crystal malt

100g amber malt

40g Whitbread Golding Variety hops, blended with 25g Fuggles hops

4 tsp gypsum

1 tsp cooking salt

2 tsp dried carragheen

11g sachet English ale yeast

15g Fuggles hops (for dry-hopping)

50g sugar for priming

Place the malts in a fermenting vessel and stir in 7.5 litres water heated to 75°C. The mash heat should be 64°C. Cover and maintain this temperature for 40 minutes, then stir in 3 litres water at 76°C. Cover and keep warm for a further 50 minutes.

Sparge with water at 78°C until you have 25 litres wort.

Pour the wort into your copper and boil for a total of 1¾ hours. Add 50g of the Whitbread Golding and Fuggles hop blend, the gypsum and salt at copper-up and the remaining hop blend and carragheen at 1½ hours. Let stand for half an hour.

Transfer to your fermenting bucket, straining out the used hops, liquor down until the specific gravity is at 1038, then cool rapidly.

At 20°C aerate and then pitch the yeast. Leave for about 5 days until fermentation is complete and the specific gravity is about 1011.

Rack into a barrel or wide-neck fermenting vessel with the Fuggles dry-hopping hops in a bag. Leave for 2 weeks, rumbling every now and then.

Prime as usual, depending on whether the brew is to be bottled or left in cask.

Aleister Crowley’s AK bitter

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1031 | 3.1% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1007 |

This rather weak, low-hopped beer would probably be described as a ‘mild’ these days, but Crowley & Co. called it a ‘bitter’ so we shall stick with that. It may come as a surprise that this odd and notorious occultist – once called ‘the most evil man that ever lived’ – had anything to do with brewing and, truth be told, he didn’t. Crowley & Co. was sold in 1879 and Aleister lived on the inheritance so derived. The origin of ‘AK’ has been the subject of much speculation but one explanation is that it is an abbreviation of ankel koyt, a type of pale beer from northern Germany.

Makes about 25 litres

3kg English pale ale malt

250g crystal malt

60g East Kent Golding hops

350g Edme SFX dark malt extract (or similar)

10g gypsum

2 tsp dried carragheen

11g sachet English ale yeast

50g sugar for priming

Place the malts in a fermenting vessel and stir in 7 litres water heated to 73°C. The mash heat should be 63°C. Cover and keep warm for half an hour.

Stir in 2.5 litres water at 82°C. Cover and keep warm for another hour.

Sparge with water at 75°C until you have 25 litres wort. Transfer to your copper.

Boil for a total of 1½hours. Add 35g hops, the malt extract and gypsum at copper-up then another 15g hops and the carragheen after 1 hour. Let stand for half an hour.

Pour into a fermenting vessel, straining out the used hops, then liquor down until the wort reaches a specific gravity of 1031. Cool quickly.

Aerate, and then pitch the yeast at about 20°C. Leave to ferment for about 5 days, skimming after 2 days, and again after another day.

Once the beer reaches a specific gravity of 1007, rack into a barrel or wide-neck fermenting vessel, adding the remaining 10g hops in a muslin bag. Leave for at least 3 weeks, rumbling the barrel or fermenter every now and then.

Prime as usual, depending on whether the brew is to be bottled or left in cask.

Strong East India pale ale

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1066 | 6.8% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1014 |

It began with a problem. The British of the Raj, like the British everywhere else, liked their tipples. Beer was the solace of choice for most of them but beer is not easily brewed in the subcontinent, at least not until fairly recently. Madeira was consumed by the boatload, but there is only so much Madeira you can drink, and palm sugar wine and its distilled offspring, arrack, were consumed in vast quantities to provide variety and economy. However, they were deadly brews, notoriously, on one occasion, claiming the lives of several Englishmen during a single evening bash. A less troublesome replacement was needed.

Unfortunately, beer does not travel well over such distances and certainly not at the temperatures it encounters while travelling them; it almost invariably went bad. Several solutions were suggested, such as making a concentrated wort, shipping that and adding water and yeast when it arrived – a sort of beer ‘pot noodle’. It did not work well.

The answer was simply to make a beer that kept well. Enter Mr Hodgson of Bow Brewery in East London. Two things stop beer having the shelf life of milk: alcohol and hops. Mr Hodgson’s simple solution was to increase both – a lot. His India pale ale used heroic quantities of malt and hops, with extra hops added to the finished beer just in case. He also primed the beer with a greater than usual amount of sugar so that the barrels gently fizzed all the way to India; a live beer is unlikely to go sour.

Modern IPAs are, for the most part, poor imitations of Mr Hodgson’s original brew and most are really just bitters. The alcohol content is usually a paltry 4.5% and a journey to the Isle of Wight can be touch and go. However, you can pickle a dog in this 6.8% beer.

The recipe is taken from a brew made in Swanage, Dorset, at the height of British influence in India. It has a back-breaking malt bill and a wallet-threatening hop bill, but it is a truly remarkable beer. It is extremely aromatic because of the high level and varieties of alcohols and esters it produces, and thick enough to stand a spoon in upright (though only a metal spoon; plastic ones dissolve).

Finally, there is the delightful bonus of my Small beer, which must be made very soon after, or even at the same time as, the IPA. You will be very busy juggling pots and buckets so try to keep focused and don’t plan to do anything else that day.

Be warned, this is strong stuff and the higher alcohol content makes it almost immediately soporific. Fortunately it has never given me a hangover as I have always fallen asleep after one pint.

Makes about 25 litres

9.5kg English pale ale malt

1kg crystal malt

4 tsp gypsum

190g East Kent Golding hops

2 tsp dried carragheen

2 x 11.5g sachets high-alcohol yeast, such as Safbrew S-33

50g sugar for priming

Put the malts in a large fermenting bucket; you will probably need to employ your 33-litre bucket for this. Heat 21 litres water to 74°C and mix with the malts in the bucket. The mash heat should be 64°C. Cover and keep warm for 1½ hours.

Sparge with water at 78°C until you get 25 litres wort. Now if you also wish to make the recipe here (and you really should, otherwise the leftover sugar-rich mash is wasted) you have to start it at this point!

Pour the wort into your copper. Boil for 1¾ hours, adding the gypsum and 90g of the hops at copper-up, another 90g hops after 1 hour and the carragheen after 1 hour 20 minutes. Allow to stand for half an hour.

Pour into a fermenting vessel, sieving out the used hops, then liquor down until the wort reaches a specific gravity of about 1066. Cool quickly.

When it is at room temperature pitch both sachets of yeast – you need an extra dose because yeast can struggle to get going at high sugar concentrations. Cover and leave to ferment for about 5 days. After 2 days skim off the foam and do this again the next day.

Once it reaches a specific gravity of 1014, rack the beer into a barrel or wide-necked fermenting vessel, adding the remaining 10g hops tied in a muslin bag. Give the hops a month to infuse the beer, rumbling for the first 2 weeks.

Prime with sugar as usual, depending on whether you intend to bottle or keep your beer in cask. Either way, this beer benefits enormously from being left to mature for a few months. Drink with extreme caution.

Strong East India pale ale

Small beer

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1035 | 3.7% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1007 |

This beer follows on from the IPA here and it is frankly not that small. It uses ‘parti-gyling’, which is not something you hear much of these days. Most recipes make an ‘entire’ beer; i.e. malt is used to make a single beer and then thrown away. Parti-gyling is where you make a strong beer from the first sparging of the malt and a weaker beer from the second sparging; sometimes a third beer is made, and this is a ‘small beer’. These three beers can be blended, providing yet more variation.

But three spargings is a lot to ask from the home brewer so we shall content ourselves with two. When you make your IPA you should be prepared with extra 25- and 33-litre fermenting vessels because this beer must be made the same day.

The partially used malt left over from the IPA should be still hot and where you left it in the mash bag and fermenting bucket-cum-colander.

Makes about 25 litres

Malt left over from the IPA (here)

60g East Kent Golding hops

2 tsp dried carragheen

11g sachet English ale yeast

1 tsp beer finings

50g sugar for priming

Heat 25 litres water to 78°C. Place a fresh fermenting bucket under the bucket/sieve containing the partially sparged malt and sparge with the hot water until the specific gravity of the wort is down to 1035. You will need to test quite often to avoid over-diluting it. How much wort you will get depends on many factors; you may not get 25 litres in which case adjust the amount of hops accordingly.

Pour the wort into your copper. Boil for a total of 1¼ hours, adding 20g of the hops at copper-up, another 20g hops and the carragheen at 1 hour, and the final 20g hops 5 minutes from the end. Allow to stand for 40 minutes.

Transfer to your fermenting bucket, straining out the used hops, liquor down until the specific gravity is at 1035, then cool rapidly.

Aerate and pitch the yeast at 20°C. Leave to ferment for about 5 days until fermentation is complete and the specific gravity is about 1007.

Rack into a barrel or fermenter, then continue with finings and sugar as usual, depending whether you want a cask-conditioned or bottle-conditioned beer.

John Wright & Sons

Experimental India beer

| ORIGINAL GRAVITY | 1050–1054 | 4.7–5.2% ABV |

| FINAL GRAVITY | 1014 |

Since I have only daughters you can be assured that the John Wright in question is another fellow altogether. He was in fact a Scot whose company brewed from the early nineteenth century in Perth, Scotland. It is his company, not he, that is responsible for this beer, since he died in 1849, over fifty years before it was brewed.