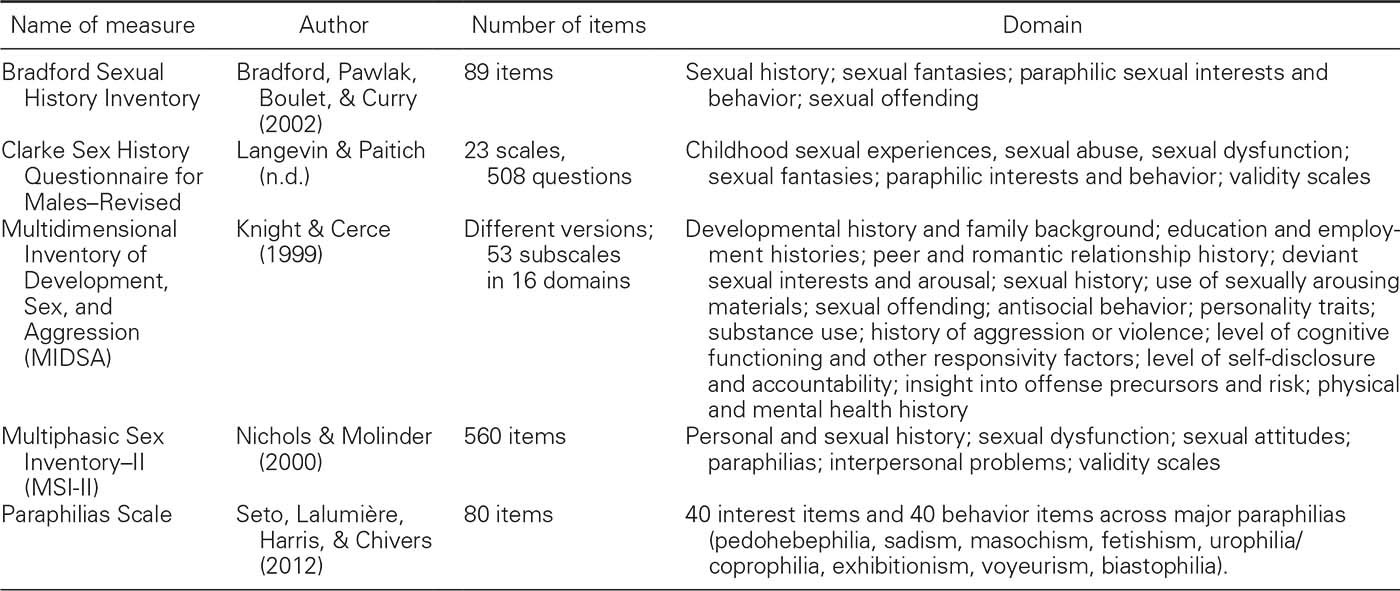

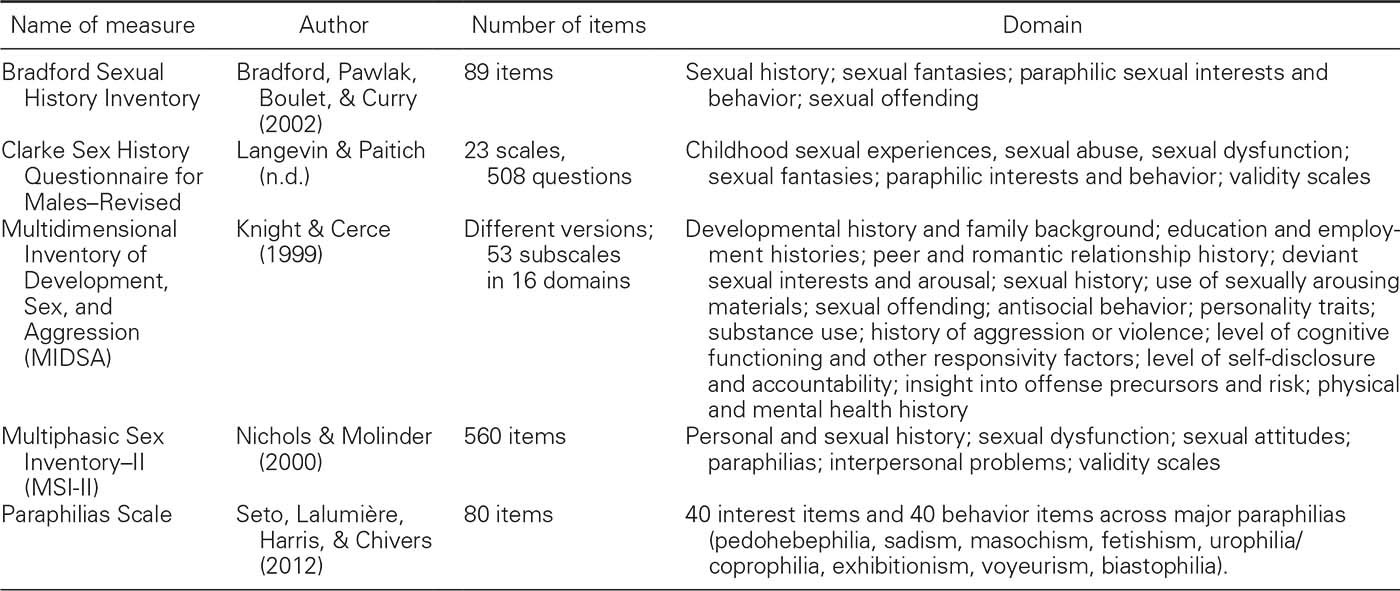

TABLE 2.1

Clinical Assessment Measures for Pedophilia (and Other Paraphilias)

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

To complement self-report, sexual behavior regarding child pornography use or sexual contacts with children can be considered, including details such as number of child victims, their ages, and whether the person was a regular user of child pornography. Traditionally, this information is subjectively considered to provide a clinical opinion about pedophilia. However, sexual behavior can also be considered in a structured way, using a measure such as the Screening Scale for Pedophilic Interests (SSPI; Seto & Lalumière, 2001) or its revised version (SSPI-2; Seto, Sandler, & Freeman, 2017; Seto, Stephens, et al., 2017). (See my ResearchGate profile—in the author biography—for a project page that includes a SSPI-2 scoring guide, conference handouts, and other relevant documents. The SSPI and SSPI-2 are freely available and free to use.)

Screening Scale for Pedophilic Interests

The SSPI was developed with the knowledge that among identified offenders with child victims, those with any boy victims (vs. girls only), multiple child victims (vs. a single child victim), younger child victims (vs. older child victims), and unrelated victims (vs. intrafamilial victims) were more likely to have pedophilia.

Child victims

were defined as under the age of 14 when the SSPI was developed because that was the legal age of consent in Canada at the time; it is now 16, more in line with many American states.

Extrafamiliality

was defined as any child who was not the offender’s son or daughter, sibling, stepson or stepdaughter, niece or nephew, grandchild, or first cousin. The large majority of related victims in the SSPI development sample were offspring or stepoffspring, that is, daughters, sons, stepdaughters, and stepsons.

Other correlates were considered, but we wanted a brief, easy-to-use, and easy-to-score measure for clinicians or researchers who did not have access to more comprehensive assessment data, especially phallometric testing of sexual arousal to children. We used phallometrically derived indices of sexual response as our criterion for suggesting pedophilia rather than diagnosis in developing the SSPI and then SSPI-2 because of the subjective nature of psychiatric diagnosis and questions about the interrater reliability and validity of the pedophilia diagnosis in particular (see Seto, Fedoroff, et al., 2016). Also, at the time the SSPI was developed, phallometric testing was considered the best option for discerning sexual interest in children without relying on self-report.

The SSPI was developed in a large sample of 1,113 adult male sex offenders with child victims (Seto & Lalumière, 2001) and has only four items, scored dichotomously as present or absent. Each item received 1 point if present, except for having a boy victim, which preliminary analysis suggested had much more weight in predicting phallometric responding (and thus this item received 2 points if present). Total scores ranged from 0 to 5, where an offender with a score of 0 had only one female victim, ages 12 or 13, who was related to him (single girl victim incest offender), whereas an offender with a score of 5 had multiple child victims, at least one of which was male, under age 12, and unrelated to him. Approximately one in five sex offenders with a SSPI score of 0 showed greater sexual arousal to children than to adults when assessed phallometrically, whereas almost three in four sex offenders with a score of 5 showed this pattern of sexual response.

The SSPI is scored using information from both self-report and file information. If the person admits to more sexual victims than are officially recorded, information about those additional victims is used on the assumption that someone being assessed, especially as part of legal proceedings, would not admit to victims that did not exist. However, if the person denies victims that are officially recorded, the file information is used instead.

The SSPI can be understood as a brief measure of pedophilic sexual interests, operationalized as sexual arousal to children relative to adults as assessed using phallometric testing (see the section below). In our original study, SSPI scores were positively and moderately correlated with an index of relative sexual arousal to children (Seto & Lalumière, 2001). A similar but smaller positive association was found in a subsequent study of adolescent sex offenders with child victims (Seto, Murphy, Page, & Ennis, 2003) and in other studies of adult sex offenders with child victims (Banse, Schmidt, & Clarbour, 2010; Canales, Olver, & Wong, 2009; Mokros, Dombert, Osterheider, Zappalè, & Santtila, 2010). The SSPI was developed as a sexological assessment measure, but a number of studies have looked at its predictive validity for recidivism. Seto, Harris, Rice, and Barbaree (2004) found that SSPI scores predicted violent (including contact sexual) recidivism, as did Helmus, Ó Ciardha, and Seto (2015) using data from the Dynamic Supervision Project. On the other hand, other studies have not found the SSPI to be a significant predictor of sexual recidivism, including among adolescent offenders (Fanniff & Becker, 2005; Moulden, Firestone, Kingston, & Bradford, 2009).

Since the SSPI was published, it has been taken up in a variety of clinical contexts, perhaps because it is freely available, relatively easy to score with adequate file information, and readily interpretable. Besides individual evaluators who think the measure can provide useful information about sexual interest in children, I discovered in an informal survey in February 2014 on the LISTSERV for the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (the largest international organization of professionals working with sexual offenders;

http://www.atsa.com

) that the SSPI was routinely used for all candidates for sex offender civil management by the New York Office of Mental Health, in the Arkansas and Minnesota Departments of Corrections, Minnesota Sex Offender Treatment Program, and by evaluators of candidates for civil commitment in North Dakota and Wisconsin. The SSPI is an accepted substitute for phallometric testing in the second edition of the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide (Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Cormier, 2006) and explicitly anchors the sexual interest item in the Sex Offender Treatment Intervention and Progress Scale (McGrath, Lasher, & Cumming, 2012).

Revised Screening Scale for Pedophilic Interests

The SSPI was revised in 2014 because of information in the intervening decade showing an increase in child pornography offending and evidence that child pornography offending itself was a strong indicator of sexual arousal to children (Blanchard et al., 2007; Seto, Cantor, & Blanchard, 2006). The SSPI-2 comprises five items, the original four SSPI items plus a new item regarding charges for child pornography offending (Seto, Stephens, et al., 2017). Several points should be kept in mind in considering the SSPI-2: (a) Preliminary analysis showed that the double weighting for having a boy victim adversely affected the predictive performance of the scale, so we used unitary weights for all five items, and thus scores still range from 0 to 5; (b) the legal age of consent in Canada—where the development research took place—changed in 2008 and data were recorded differently at the clinic where data were collected; and (c) the measure is still intended for contact offenders with child victims, including those who have also committed child pornography offenses—it is not intended for child-pornography-only offenders because these individuals cannot be scored on the original SSPI items without any known contact sexual offending history.

The SSPI-2 correlated positively and significantly with ratings of sexual preoccupation, emotional identification with children, and sexual-offense-related cognitions (convergent validity) but was not significantly related to ratings of self-regulation problems, noncompliance with supervision, or antisocial personality (divergent validity; Seto, Sandler, & Freeman, 2017). Also, the SSPI-2 performed slightly better than the SSPI in predicting sexual rearrest in a sample of 2,416 New York offenders.

Self-report plus behavior can perform better as predictors of sexual recidivism than either set of indicators alone (Stephens, Cantor, Goodwill, & Seto, 2017). A potential problem with a behavior-based measure is that first-time sex offenders might not have a history that reflects their sexual interests. This might explain why associations seem to be weaker for adolescent offenders who have had less opportunity than their adult counterparts. However, Seto et al. (2004) found that the SSPI correlated with recidivism among first time offenders as well as it did for repeat adult offenders. Also, first time offenders might have charges for historical offenses that reflect their sexual victim history.

LABORATORY TESTS

I review polygraphy and phallometry in the next section as psychophysiological measures that can produce relevant information for the ascertainment of pedophilia or hebephilia. Here, the focus is on laboratory tasks that assess sexual interests through behavior, such as forced choice responses or visual reaction time.

Viewing Time

The most studied approach in this domain involves assessment tools based on viewing time or visual reaction time. The basic viewing-time procedure for assessing pedophilia involves showing a series of pictures of children, adolescents, or adults while asking respondents to rate (e.g., physical attractiveness) or otherwise interact with the images. The persons can be depicted as clothed, semiclothed, or nude, and some stimulus sets are computer generated and do not involve any identifiable persons. Respondents are instructed to view each image at their own pace and are supposed to be unaware that the amount of time they spend looking at each image is being recorded. Multiple studies have found that unobtrusively recorded viewing time is correlated with self-reported sexual interests and phallometric responding in nonoffending volunteers who are recruited from the community (Quinsey, Ketsetzis, Earls, & Karamanoukian, 1996). In their recent meta-analysis of 14 studies, with a total sample of 2,705 men, Schmidt, Babchishin, and Lehmann (2017) found a moderate effect size for viewing-time measures to distinguish sexual offenders against children from other men. Viewing-time scores were significantly although not strongly correlated with other relevant measures, including self-report (

r

= .38), phallometric testing (

r

= .25), and the SSPI (

r

= .21).

The Abel Assessment of Sexual Interests (Abel, Huffman, Warberg, & Holland, 1998) is a proprietary measure that combines viewing time (described as visual reaction time) and responses to a computer-administered questionnaire regarding sexual interests and history. The Abel Assessment appears to distinguish sex offenders with child victims from other men whose victims are not children, and to distinguish those with boy victims only from those with girl victims only (Abel et al., 1998; Abel, Jordan, Hand, Holland, & Phipps, 2001). So far, a single predictive validity study has been published in a peer-reviewed journal: Visual reaction time predicted sexual recidivism in two samples, one of 284 men who sought evaluation or treatment for “deviant sexual behaviors” and were followed for 15 years, and the second of 337 males ages 17 to 95 (mean age of 40) who sought evaluation or treatment for the same kinds of concerns and were followed for 7 years (Gray et al., 2015). Combined, 36% had committed sexual offenses against children; 19%, voyeurism; 13%, public exposure; 3%, rape. A total of 22 individuals sexually reoffended during the follow-up period, defined as new arrests or charges for sexual offenses. To illustrate the association, the participants were divided into three groups, one at least one standard deviation below the mean visual reaction time (

n

= 97, 0% reoffended); a group within one standard deviation of the mean (

n

= 432, 7% recidivism), and a group at least one standard deviation above the mean (

n

= 92, 27%). The results were not reported in terms of receiver operating characteristic or survival analyses, which are more conventional ways of reporting predictive accuracy (see

Chapter 7

, this volume). Surprisingly, given the visual reaction time scores were based on relative response to children, whether participants had sexually offended against children or committed other kinds of sexual offenses did not add to the predictive validity of visual reaction time.

A concern, in my opinion, is that the Abel Assessment scoring algorithm is proprietary and the scoring is done by the company, and so test results cannot be independently verified by others. Evaluators might be comfortable using the measure for clinical assessments, but they might be less comfortable when trying to explain scores and how they were derived if testifying in court or when cross-examined regarding their results (see Chammah, 2015). A potential problem for all viewing-time measures is that they may become vulnerable to faking once the client learns that viewing time is the key variable of interest. I am not aware of any peer-reviewed studies that have reported on the ability of participants to fake their responses on viewing-time measures or the ability of examiners to detect faking.

Other Cognitive Assessment Tasks

In the past decade, interest has surged in adapting a range of cognitive science tasks to implicitly assess attention, motivation, and other cognitive processes that would be relevant to understanding pedophilia and hebephilia. These include tasks based on choice reaction time, cognitive interference tasks, such as the Stroop (Smith & Waterman, 2004) and rapid sequential visual presentation (RSVP), and the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Among the several reasons for this increased interest in alternative measures is that alternative measures have been developed that (a) are more acceptable to participants, (b) can be used with nonoffending individuals with pedophilia or with nonidentified offenders, and (c) can elucidate mechanisms. For example, Imhoff et al. (2010) conducted a set of experiments with a total of 250 community volunteers to try and understand which cognitive processes underlie viewing-time effects. The results did not support explanations based on deliberate delay (the person likes looking longer at a preferred image) or automatic attention to sexually attractive stimuli. Instead, Imhoff et al. argued for a mate-matching explanation as the most plausible, where it takes processing time to match the image against the person’s preferred schema. Effects could still be detected for showing only heads, not entire figures, or when administering images for a fixed time.

Choice Reaction Time

Wright and Adams (1994, 1999) described a choice reaction time task in which participants were instructed to locate a dot that appeared on slides depicting nude men or women as quickly as possible. In both studies, volunteers took longer to react to dots that appeared when viewing a picture of someone of their preferred sex (women for heterosexual men or lesbian women; men for gay men and heterosexual women). Mokros et al. (2010) compared responses of 21 offenders with child victims and 21 non–sex offenders, and indeed the sex offenders took longer to respond when dots were superimposed on images of children relative to images of adults, whereas the presumed teleiophilic comparison subjects took longer when they saw images of adults. Evidence indicated that sexual content induced delay because the effect was stronger with depictions of nude persons versus clothed persons.

On the other hand, Rönspies et al. (2015) compared 87 heterosexual men and 35 gay men on a variety of these cognitive tasks and found the viewing-time measure performed better than the choice reaction time measure in distinguishing the two groups. Banse et al. (2010) also found that the viewing-time measure performed better than implicit association (see the upcoming section) in distinguishing 38 sex offenders against children from 37 offender and 38 nonoffending controls, although the implicit measure added some unique variance in a multivariate analysis.

Stroop

Smith and Waterman (2004) evaluated the usefulness of a modified Stroop task to distinguish sex offenders, violent offenders, and nonoffenders. In the modified Stroop, participants had to name the colors in which different words—sexual, violent, or neutral in their meaning—were printed. Sex offenders were distinguished from the other two groups by their response latencies to sexual words, but sex offenders against adults did not differ from those against children in their response to sexual words; they did, however, differ in their response to violent words. Ó Ciardha and Gormley (2012) compared 24 sex offenders against children under the age of 16 with 24 nonoffending controls and also found evidence of group discrimination: Participants who had offended against unrelated children or who admitted to being sexually interested in children showed a bigger effect than intrafamilial only offenders or those who denied any pedophilic sexual interest.

Rapid Sequential Visual Presentation

Kalmus and Beech (2005) described an RSVP task in which pictures of clothed children or an animal (comparison object) were embedded in a rapidly presented series of ordinary images, followed by a task to report whether the target object had appeared and what direction it faced if it did appear. Compared with nonoffending controls, sex offenders against children made more errors when the target object appeared in a series that contained images of children. Flak (2011) also found evidence that RSVP performance could distinguish 14 extrafamilial sex offenders against children from 17 non–sex offender controls, whereas the 12 intrafamilial offenders did not differ. As further evidence of the validity of the RSVP, Flak looked at the performance of 11 new fathers with children under the age of 2; these fathers might be thought to show an attention bias for child stimuli, but they in fact did not differ from controls.

Zappalè, Antfolk, Dombert, Mokros, and Santtila (2016) found support for the RSVP task with a larger sample and more comparison groups: 69 sex offenders against children, 43 other sex offenders, 14 non–sex offenders, and 88 community controls shown stimuli differing in age and gender. Preferred stimuli elicited faster responses than nonpreferred stimuli and partial support for interference because of attentional blink. However, task performance was deemed to be insufficient for diagnosis.

Implicit Association Test

The IAT is a measure of implicit cognition drawn from social psychology to study socially sensitive topics such as racial stereotyping (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998). In the sexual interest realm, IAT involves the recording of reaction times to multiple pairings of concepts such as “adult” and “child” with attributes such as “sexy” or “not sexy.” Reaction times for personally congruous associations are expected to be faster than for incongruous associations. For a teleiophilic participant, the congruous association would be adult–sexy and child–not-sexy, whereas for a pedohebephilic participant, the congruous association would be adult–not-sexy and child–sexy. Babchishin, Nunes, and Hermann (2013) identified 12 studies (total of 707 participants) that used the IAT to assess implicit cognitions about children and sex. The IAT was able to significantly distinguish offenders against children from others, with the largest difference for nonoffenders, followed by non–sexual offenders and offenders against adults. IAT responding was positively and similarly correlated with self-reported sexual interest in children, sexual offending history, and viewing time.

Summary of Cognitive Tests

Each of the cognitive science tasks discussed in this section has advantages and disadvantages. None of them are quite ready for clinical use. An interesting question is how well scores on these implicit tasks could add to the other assessment methods. Banse et al. (2010) conducted a multimethod study using the Explicit and Implicit Sexual Interest Profile (EISIP), which combines self-report, viewing time, and IAT performance, to compare 38 offenders with child victims, 37 other offenders, and 38 nonoffending controls. Viewing time performed better than IAT, but IAT did add incrementally in multivariate analyses, such that the combination of implicit measures provided good discriminative validity.

A big question is whether these measures have predictive validity in terms of treatment response; proximate behaviors of concern, such as sexually fantasizing about children; and sexual recidivism. Schmidt, Gykiere, Vanhoeck, Mann, and Banse (2014) found that the EISIP distinguished intrafamilial, extrafamilial, and child pornography offenders as expected and that EISIP scores were negatively correlated with antisociality, positive correlated with sexual offending behavior as represented in the SSPI, and positively correlated with risk of sexual recidivism as estimated by the Static-99R (see

Chapter 7

, this volume). This evidence of divergent and convergent validity does not substitute for evidence of predictive validity, however.

Most of these implicit assessment studies have relied on nonoffending controls or non–sex offenders, which makes it hard to know how precise any observed effects are. The best comparison group might be sex offenders against adults, because they are similar in having a criminal history and having committed sexual offenses but they are different because they are very unlikely to have a sexual interest in children. Also, not all sex offenders against children are pedophilic; some lab effects should be stronger for pedophilic offenders. The strongest test of these new paradigms would be to compare (a) pedophilic and nonpedophilic offenders against children with (b) pedophilic and nonpedophilic nonoffending men.

PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MEASURES

In this section, I cover three different psychophysiological approaches, the first relying on polygraph interviewing, which is commonly used in the United States; the second, on phallometric measurement of penile responses; and the third looking at brain activation changes in response to sexual stimuli, an emerging area for neuroscientific discovery.

Polygraphy

Polygraphy involves the recording of psychophysiological parameters, such as heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and skin conductance, while the subject is asked specific questions. Polygraphy is not a method of assessing sexual interests per se but can be used as a means of checking the validity of self-report. I include it in this section because it is widely used for clinical and criminal justice supervision in the United States. In a 2000 U.S. survey, more than half of the probation/parole agencies that responded reported regularly using polygraph testing to monitor the treatment and supervision compliance of sex offenders living in the community (English, Jones, Pasini-Hill, Patrick, & Cooley-Towell, 2000). A majority (79%) of U.S. treatment programs reported the use of polygraphy as part of their practice in the 2009 Safer Society survey, compared with less than 10% of Canadian programs (McGrath, Cumming, Burchard, Zeoli, & Ellerby, 2010).

The most relevant polygraph test in the assessment of sex offenders involves the control question test, in which subjects are asked relevant questions (e.g., their sexual offense history or involvement in potentially risky activities, such as being with children alone) and their psychophysiological responses are compared with those obtained when asked neutral control questions. There is a great deal of controversy about the validity of polygraphy as a method of lie detection (see, e.g., National Research Council, Committee to Review the Scientific Evidence on the Polygraph, 2003). The most plausible interpretation is that it acts as a bogus pipeline, in which participants who believe the method works are less likely to be deceptive. Substantial research has been conducted on the impact of a bogus pipeline—attaching participants to a nonfunctioning machine they are told can detect lying—in disclosure of sensitive information (e.g., Grubin, 2016; Roese & Jamieson, 1993).

Some evidence indicates that offenders who undergo polygraph testing report more sexual victims and more sexual offenses than officially recorded (Ahlmeyer, Heil, McKee, & English, 2000; Hindman & Peters, 2001). I think it is insufficiently appreciated that some of these new disclosures might be false confessions. The false confession literature suggests that individuals who are lower in intelligence or higher in suggestibility are more likely to make false disclosures, especially when combined with high pressure interrogation tactics (see Kassin, 2005). Despite controversies about the validity of lie detection or the value of disclosures, some users do make judgments based on the results, with significant clinical and legal repercussions. This is particularly striking given there is no evidence that using polygraph interviewing reduces sexual recidivism (McGrath, Cumming, Hoke, & Bonn-Miller, 2007) or enhances risk assessment, inasmuch as self-disclosed sexual offending or other behavior might add to what is already known through ordinary interviews, collateral informants, and file review.

Phallometry

Phallometry involves the measurement of penile responses to sexual stimuli varying on the dimensions of interest, such as the age and gender of depicted persons in a series of images. Responses are usually recorded in terms of circumference change, although a few labs record total change in penile volume (see

Figures 2.1

and

2.2

). Phallometric responses are positively and moderately correlated with self-reported sexual arousal (Chivers, Seto, Lalumière, Laan, & Grimbos, 2010). Several decades of research have shown that measuring phallometric responding (originally developed by Freund, 1963, 1967) can distinguish sex offenders against children from other sex offenders, non–sex offenders, and nonoffending men. Moreover, phallometric responding is correlated with sexual offense history (recall the SSPI and SSPI-2) and with other measures of sexual interest, such as viewing time (Schmidt et al., 2017).