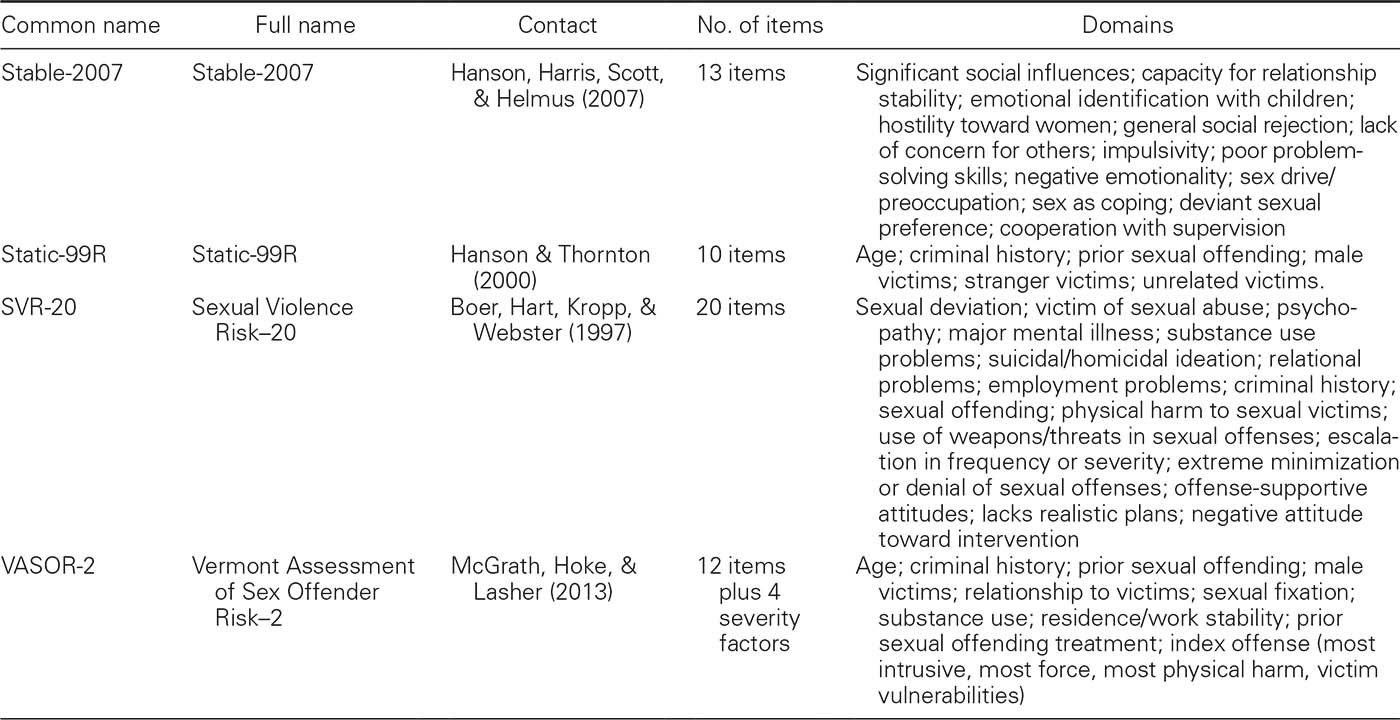

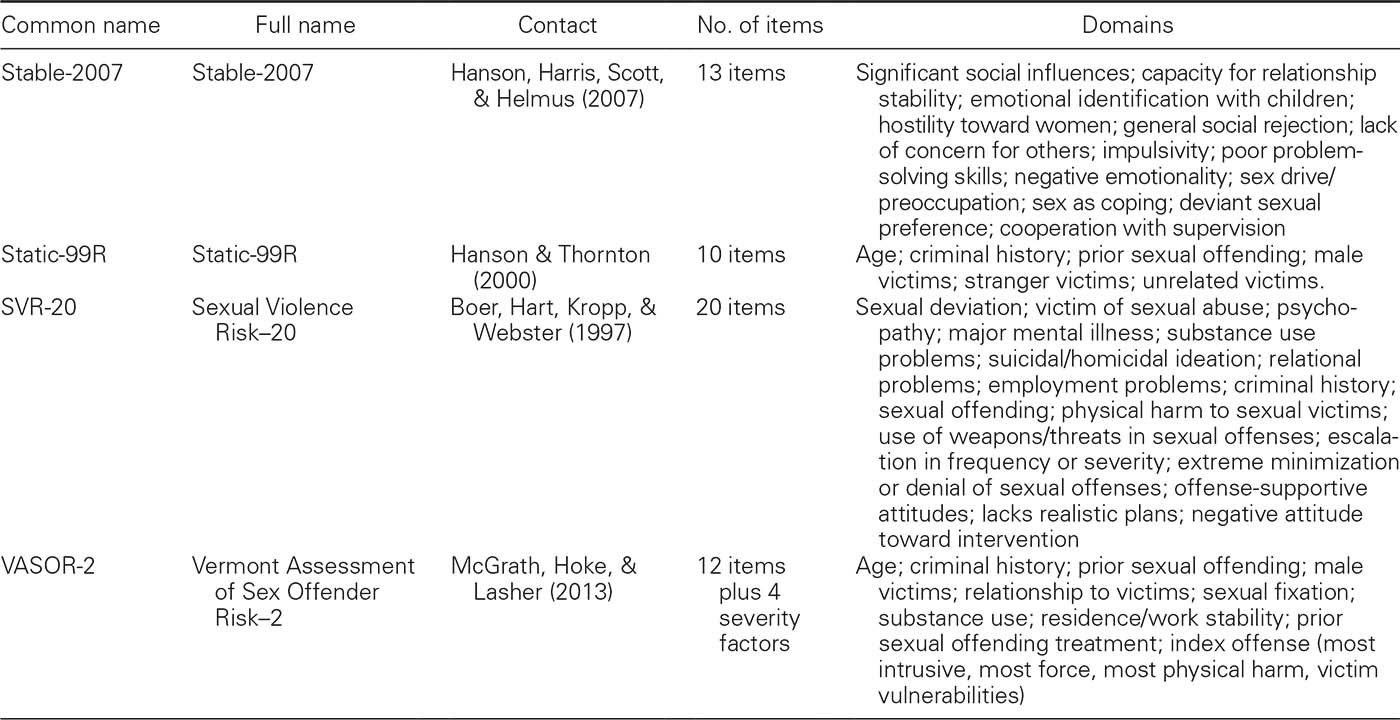

TABLE 7.1

Actuarial and Structured Judgment Sex Offender Risk Measures (Continued

)

The Static-99 was developed for adult male sex offenders. It has 10 items: offender age; ever lived with lover for at least 2 years; index conviction for nonsexual violence; prior nonsexual violence; prior sexual offenses; prior sentencing dates; any convictions for noncontact sexual offenses; any unrelated victims; any stranger victims; any male victims. Total scores can range from 0 to 12 and offenders are assigned to one of seven risk categories based on their score; individuals with scores of 6 or more are combined into one group. The Static-99R has the same items, except the weighting of the offender age item is different. Readers are referred to the Static-99 website (

http://www.static99.org

) for more information about these measures, including the latest version of the coding guide and an ongoing bibliography of validation studies.

As its name implies, the Static-99R relies on static or historical risk factors that cannot or are unlikely to change over time. Thus, once someone’s long-term risk to reoffend is determined, that is their risk level going forward, irrespective of changes in treatment or supervision or circumstances. However, the Static-99R can be combined with a dynamic risk measure, the Stable-2007, and has an empirically justified adjustment for time spent living offense-free in the community. Dynamic risk assessment is discussed further in a later section.

Which Risk Scale Is Best?

Hanson and Morton-Bourgon (2009) reported the results of a meta-analysis comprising 118 different samples, representing more than 45,000 sex offenders in 16 countries. In this meta-analysis, they compared unstructured, structured, and actuarial risk assessment approaches. As expected, unstructured risk assessment fared the worst and actuarial risk measures were the most accurate, on average, with moderate to large effect sizes by conventional guidelines; structured risk measures fell in the middle. Structured risk measures can be scored by summing or counting items or by invoking subjective integration of scores, potentially recapitulating some of the problems of unstructured risk assessment. However, structured professional judgment advocates point out that measures are not supposed to be scored by summing or counting risk items. Instead, evaluators are asked to make a global judgment, taking into account critical factors or other considerations, in order to guide their case formulation and planning. The Hanson et al. (2009) meta-analysis found support for this global judgment approach over mechanical scoring for the SVR-20, but the evidence was more mixed for other structured risk measures.

Hanson and Morton-Bourgon (2009) identified 63 replications of the Static-99/99R, with many of these by teams independent of the developers. The MnSOST-R had a higher average effect size, but only 12 replications were identified in the review. Studies that have directly compared actuarial risk scales have not found consistent differences in their predictive performances in predicting violent or sexual recidivism (Barbaree, Seto, Langton, & Peacock, 2001; Dempster, 1999; Langton et al., 2007; Nunes, Firestone, Bradford, Greenberg, & Broom, 2002; Sjöstedt & Långström, 2001). A methodological issue to keep in mind is that developers tend to find (or report) better results than independent investigators, a so-called allegiance effect (Blair, Marcus, & Boccaccini, 2008; see also J. P. Singh, Grann, & Fazel, 2013).

The most parsimonious explanation for the lack of consistent differences across established risk measures in their relative predictive accuracy is that they share a great deal of item content and assessment methods. It is therefore not surprising that Kroner, Mills, and Reddon (2005) found that four general risk measures, that is, the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised, Level of Service Inventory—Revised, Violence Risk Appraisal Guide, and the General Statistical Information on Recidivism, did not significantly differ in their predictive accuracies from four new scales that were created using a quasi-random subset of items from these four measures. Moreover, the quasi-randomly generated scales and the original measures were all significantly and positively correlated with each other. If the similar items and method explanation for the similarity across measures is correct, then only the addition of new items representing content that is not captured by existing items, and/or collected using different methods (e.g., brain imaging, neurochemical assays) could add to the already good predictive accuracies that can be obtained when assessment data are sound (e.g., little or no missing data, reliably coded) and outcomes are comprehensive. G. T. Harris and Rice (2003) argued that actuarial risk scales scored with complete information and high reliability may have already reached a predictive ceiling.

Helmus et al. (2012) noted that many studies have replicated the predictive validity of the best-known actuarial risk measures in terms of discrimination of recidivists from nonrecidivists but few have examined the calibration of recidivism rate estimates. AUC is a good index of relative risk accuracy in terms of discrimination, that is, distinguishing higher and lower risk offenders. A different index is needed to capture absolute risk accuracy, reflecting the calibration of a risk scale in terms of the gap between observed and expected recidivism rates. Helmus and her team therefore conducted a meta-analysis of 23 samples (comprising a total of 8,109 sex offenders) using the Static-99R and Static-2002R. Relative risk estimates, reflecting discrimination of higher and lower risk offenders, were robust across samples. However, absolute recidivism rates varied significantly, indicating calibration is an important issue in evaluating risk measures (if decisions are being made on the basis of the accuracy of probabilistic estimates, as opposed to relative risk or rank order; see Hanson, 2017).

DYNAMIC RISK ASSESSMENT

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, actuarial risk scales are exclusively or near-exclusively composed of static or historical risk factors that cannot change (e.g., prior criminal history) or that are very unlikely to change over time, at least with our current knowledge (e.g., having pedophilia). Dynamic risk factors, in contrast, are changeable factors that fluctuate over time (e.g., expression of antisocial attitudes and beliefs about sex with children) that can, at least in principle, be the targets of treatment or supervision.

Some practitioners and researchers have argued that sex offender risk assessment needs to incorporate dynamic risk information, to avoid the potential dilemma of assigning risk scores to an offender that do not change because the scores are based on static/historical factors. For example, once someone is denied parole because of their actuarially estimated risk to sexually reoffend, nothing they can subsequently do—participate in treatment, obtain a firm commitment of legal employment upon their release, improve their family support—can change that risk score. This is a dilemma for the offender, who may be less motivated to participate in treatment or other services, because they cannot change their risk score, as well as the clinician, who wants to increase offender motivation and participation in services through the incentive of increasing the likelihood of release on parole or an easing of supervision conditions.

This dilemma can be handled in different ways. One way is to reserve the option to adjust actuarial or structured risk evaluations on the basis of additional information that is not already represented in the measures, for example, successful completion of prescribed treatment or an extended period of time offense-free in the community (Hanson, Harris, Helmus, & Thornton, 2014; see below). An important question then is whether clinically adjusted risk assessments can improve, or at least not harm, predictive accuracy. Evaluators may want to incorporate irrelevant information or information that is statistically or conceptually redundant with existing items, perhaps unaware that this additional information was considered in the development of risk measures. This will reintroduce the problems of unstructured professional judgment. Another potential solution that does not compromise the predictive accuracy of actuarially estimated risk is to require more extensive preparations for release based on actuarially estimated risk, so higher risk offenders must do much more to be eligible for parole than low-risk offenders. In this arrangement, a higher risk offender might have to complete treatment, obtain employment, develop stronger family support, and meet a number of other goals to be released, whereas a lower risk offender might only have to obtain stable housing and employment for his release. In general, a more conservative or cautious stance is warranted in the management of the high-risk offender.

Integrating Static and Dynamic Risk

The way I prefer to resolve this dilemma is to view static and dynamic risk information as germane to two different questions. Static risk factors are more helpful than dynamic risk factors when answering the question of who is more likely to sexually reoffend within a known group of offenders followed for a specified period of time. Offenders with a history of alcohol use problems, for example, are more likely to sexually reoffend than offenders without such a history. Dynamic risk factors are more helpful than static risk factors when answering the question of when someone is more likely to sexually reoffend, given a specified long-term likelihood (see also Douglas & Skeem, 2005). Individuals are more likely to reoffend when they are intoxicated than when they are sober. The likelihood that an offender will sexually reoffend is not uniformly distributed over time (or space). An offense is more likely at some times and less likely at others; dynamic risk factors indicate periods of higher likelihood, that is, imminence. To illustrate this idea at the most basic level, sex offenders are at lower risk of sexually offending when asleep than when awake; being awake is a dynamic risk factor. Whether someone should be released or not should be more influenced by static risk factors; what needs to be in place in terms of intervention should be more influenced by dynamic risk factors.

Psychologically Meaningful Risk Factors

A number of dynamic, psychologically meaningful risk factors have been identified in the sexual offending literature (see Mann, Hanson, & Thornton, 2010). Dynamic risk research is difficult to conduct, which may explain why knowledge about dynamic risk factors lags the field’s knowledge about static risk factors. It is not sufficient to demonstrate that a changeable or fluctuating factor, assessed at one point in time, is related to whether a new sexual offense is committed; because the variable is assessed at only one point in time, it becomes a static risk factor when considered at a later date. Whether someone is currently intoxicated is potentially a dynamic risk factor; whether someone consumed alcohol last week is potentially a static risk factor. Indeed, even whether someone is currently intoxicated might not be truly dynamic inasmuch as it reflects the underlying latent (and static) risk factor of proneness to use alcohol (G. T. Harris, Rice, Quinsey, & Cormier, 2015; Seto & Barbaree, 1995).

To truly be a dynamic risk factor, it is necessary to demonstrate that change on the factor is related to the timing of any offense that occurs, over and above the prediction provided by static risk factors. To illustrate this last point, association with antisocial friends might be a potential dynamic risk factor because it can be measured more than once, and it can be targeted through interventions to decrease contact with antisocial friends and increase contact with prosocial friends. However, having antisocial friends may actually be a proxy for antisociality, because highly antisocial offenders tend to have more antisocial peers and fewer prosocial peers. Even demonstrating that change in peer groups is related to recidivism is not sufficient to demonstrate that this variable is truly a dynamic risk factor, because it may be the case that highly antisocial offenders do not change their peer groups easily, whereas less antisocial offenders can. Having antisocial friends would be a truly dynamic risk factor if it could be demonstrated that changing peer associations is associated with the likelihood that a new offense occurs, over and above the prediction provided by knowing whether someone is highly antisocial.

Dynamic risk research with sex offenders in the community suggests that the following factors distinguished sex offenders who reoffended from those who did not, even after the recidivists and nonrecidivists were matched on a set of static risk factors: compliance with supervision; ability to regulate sexual thoughts, fantasies, and urges; attitudes tolerant of sexual offending; and associating with antisocial peers (Hanson & Harris, 2000; Hanson, Harris, Scott, & Helmus, 2007). This information is captured in the Stable-2000 and Stable-2007 measures. The Stable-2000 has 16 items, organized into the following dynamic risk domains: significant social influences, intimacy deficits, problems with sexual self-regulation, attitudes tolerant of sexual assault, noncooperation with supervision, and problems with general self-regulation. The

significant social influences

domain is the sum of the negative and positive nonprofessional influences in a person’s life (family, friends, etc.); the

intimacy deficits

domain represents stability of any current intimate relationship, emotional identification with children, hostility toward women, general social rejection or loneliness, and a lack of concern for others; the

sexual self-regulation

domain pertains to high sex drive/sexual preoccupation, use of sex as a way of coping with negative feelings, and paraphilias; the

attitudes supportive of sexual assault

domain reflects sexual entitlement, attitudes tolerant of rape, and attitudes tolerant of adult–child sex; the

noncooperation with supervision

domain reflects lack of compliance and cooperation with supervision conditions; and the

general self-regulation

domain reflects impulsivity, poor cognitive problem-solving skills, and negative emotionality/hostility. Using a prospective study design, Hanson et al. (2007) found that Stable-2000 scores significantly predicted sexual recidivism, over and above the prediction provided by the Static-99. Seto and Fernandez (2011) showed that offenders can be classified into different dynamic risk profiles based on their Stable-2000 scores; we found evidence for a low needs group, with low scores across the dynamic risk factors; a typical group, with intermediate scores on many items; a sexually deviant group, with high scores on atypical sexual interests, sexual preoccupation, emotional identification with children, and offense-supportive attitudes about children and sex; and a pervasive high needs group, with high scores on many Stable-2000 items.

Clinical Adjustments

An ongoing debate in sex offender risk assessment is whether clinical adjustments of actuarially estimated risk to reoffend can be justified. The first of at least two positions on this is that clinical adjustments are sometimes justified because actuarial risk scales, no matter how wide-ranging in their content, do not include all possible risk and protective factors. Proponents of this position also note that actuarial risk scales do not accommodate very unusual circumstances, for example, if a pedophilic sex offender has a stroke and is severely cognitively and physically disabled as a result (and presumably becomes much less capable of sexually offending, even if still motivated to do so). The contrasting position is that clinical adjustment of actuarial estimates recapitulates the problems faced by unstructured clinical risk assessment. For example, clinicians who are familiar with an actuarial risk scale but not all the details of the research that contributed to its development may unwittingly consider factors that have already been examined and dropped in analyses that found the additional information did not add to the measure’s predictive accuracy.

If a new risk factor is identified and did add to the predictive accuracy already obtained by the existing items, it could be incorporated as a new item in a revised version of the actuarial risk scale. In other words, the adjustment of actuarial risk scale results could itself become an actuarial procedure. A good example here is time spent offense-free in the community, where an actuarially high-risk offender does not sexually reoffend. This time spent offense-free can be taken into account in the Static-99R. In the latest version coding rules for the Static-99R, Phenix et al. (2016) described how to adjust the probabilistic estimates of this measure based on the amount of time that an offender had spent in the community without any new nonsexually violent or sexual offenses.

Time Offense-Free

Analyzing recidivism data from a cumulative sample of 7,740 sex offenders followed for 20 years, Hanson et al. (2014) found that the probability of a new sexual offense decreased dramatically with time spent offense-free in the community. Indeed, the probability was approximately halved for every 5 years an offender remained offense-free. G. T. Harris and Rice (2006) examined the impact of violent offense-free time at risk in a study of the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide, an actuarial measure developed for nonsexually violent or contact sex offenders. They found that violent offense-free time at risk was related to the likelihood of new violent offenses, and that this information could be used to adjust actuarially estimated risk as long as an offender was not in the highest three risk categories. However, it is important to note that they recommended that this adjustment itself be actuarial. Specifically, G. T. Harris and Rice reported that the probability of violent recidivism (outside of the highest three risk categories on the VRAG) decreased by 1% per year. Thus, an offender could be moved to the next lower VRAG risk category after 10 years of being violent offense-free, and again to the next lower VRAG category after an additional 15 years of being violent offense-free.

Treatment Completion

It is telling that none of the major sex offender risk measures include treatment completion or noncompletion as a risk factor. One would expect that treatment completion would add to the prediction of sexual recidivism, over and above individual risk-related factors, if it had a significant impact on outcomes. However, McGrath, Cumming, Livingston, and Hoke (2003) found that whether an offender completed treatment added to the prediction of sexual recidivism obtained by the Static-99. Faust, Renaud, and Bickart (2009) found that prior sex offender treatment was associated with a greater risk of sexual rearrest in a large sample of federally sentenced child pornography offenders; a more optimistic interpretation is that prior treatment explained variance because of prior sexual offending but presumably prior sexual offending was also considered as a risk factor.

Whether treatment completion adds to the assessment of risk for recidivism is only indirect evidence for treatment efficacy. As I discuss in more depth in the

next chapter

, demonstration of efficacy requires a comparison of treated and comparison groups, because treatment completion is likely to be related to risk-relevant factors, such as antisocial personality traits. More antisocial individuals are expected to be more likely to refuse treatment in the first place, more likely to drop out, more likely to be noncompliant with treatment rules or expectations, and more likely to be terminated because of disruptive behavior. For example, Olver and Wong (2009) found that sex offenders with psychopathy were more likely to drop out of treatment, and those who dropped out were more likely to violently, but not sexually, reoffend.

Treatment Behavior

A growing number of studies have examined the relationship between treatment-related behavior—including level of participation, attitudes about treatment, and treatment-related change—and sexual recidivism. Olver, Nicholaichuk, Kingston, and Wong (2014) showed that positive treatment change scores on the VRS–SO were related to lower recidivism rates in a sample of 676 treated sex offenders followed for an average of 6 years, as expected. This was consistent with earlier work using the same measure with different sex offender samples (Olver, Wong, Nicholaichuk, & Gordon, 2007), including a study focusing on offenders with child victims (Beggs & Grace, 2011).

Wakeling, Beech, and Freemantle (2013) showed that self-reported change on psychometric measures assessing sexual interests, pro-offending attitudes, interpersonal deficits, and self-regulation problems were also related to recidivism outcomes in a large sample of 3,773 sex offenders in the United Kingdom followed for 2 years. A caveat for interpreting Wakeling et al.’s findings is that only treatment completers were followed, because those who dropped out of treatment would not have any posttreatment scores. This creates a selection bias as completers are expected to be less antisocial and more cooperative and therefore less likely to reoffend, whereas those who are more antisocial are more likely to quit or be terminated.

In principle, studies using a rating scale such as the VRS–SO could still evaluate offenders at the time they left treatment, even if it was early on. (It is not clear whether this was done for Olver et al., 2014; my reading of the methods is that they followed those who had completed treatment and therefore had both pre- and posttreatment ratings.) Seto and Barbaree (1999) raised the question of whether treatment behavior and recidivism were moderated by other factors, such as psychopathy (see

Chapter 8

, this volume).

Offender Age

Another potential adjustment factor in sex offender risk assessment is aging, which might be associated with lower sexual recidivism because of lower sex drive, lower aggression, or lower risk taking more generally. This continues to be a heated debate because of its implications for release decisions regarding older sex offenders who are actuarially high risk to sexually reoffend. Is it possible that they eventually “age out”? Barbaree, Blanchard, and Langton (2003) reported that an offender’s age-at-release was a significant predictor of sexual recidivism in a sample of 468 sex offenders; the majority (63%) had offended against at least one child. Barbaree et al. (2003) suggested this finding might reflect an age-related decrease in risk for offending, mediated by an age-related decrease in sexual arousability or sex drive (and perhaps an age-related increase in self-control).

Barbaree et al. (2003) addressed the alternative explanation that their cross-sectional data might reflect cohort differences in risk (e.g., highly antisocial offenders engaging in more physically risky activities and therefore dying at a younger age, resulting in a lower risk group of older offenders) rather than an effect of aging, by noting that the four age groups they created did not show a systematic difference in scores on a brief actuarial risk scale (the RRASOR, a precursor to the Static-99). They did not report, however, whether the offender age-at-release significantly added to the predictive performances of actuarial risk scales with a broader range of possible scores, such as the Static-99, or whether the age groups differed on these other risk scales. Barbaree et al. (2003) also did not report how offender age-at-release performed when compared with offender age at time of the index offense, or offender age at the time of his first offense, all of which are positively related to each other. This is an important question because G. T. Harris and Rice (2007) argued that offender age-at-release may actually be acting as a proxy for the historical risk factor of offender age at time of first or index offense. If this proxy explanation is correct, then offender age-at-release does not reflect an age-related decrease in risk of offending. Hanson (2002) found recidivism rates declined with age for rapists but did not decline until after age 50 for extrafamilial offenders against children. D. Thornton (2006) found an effect of offender age at release after controlling for antisociality and atypical sexual interest factors; subsequent analyses by Barbaree and colleagues (e.g., Barbaree, Langton, Blanchard, & Cantor, 2009) found that offender age at release added to age-corrected antisociality and atypical sexual interests.

Impact of Clinical Adjustments

Although clinical adjustments of structured or actuarial risk results appear to be common, relatively few studies have specifically examined the impact of clinical adjustments on predictive accuracy. Sreenivasan, Frances, and Weinberger (2010) argued for having a clinical adjustment option, whereas Abbott (2011) criticized this idea. In an early study, Barbaree et al. (2001) examined the ability of treatment-related information to add to the predictive performance of an unvalidated, structured clinical assessment measure, the Multifactorial Assessment of Sex Offender Risk for Recidivism (MASORR). Pretreatment MASORR scores did not significantly predict recidivism, whereas posttreatment MASORR scores produced an even lower AUC, indicating that the addition of treatment-related information had a negative impact on predictive accuracy. Peacock and Barbaree (2000) found that adjustments to RRASOR scores based on treatment-related behavior (e.g., level of participation in treatment) did not improve predictive accuracy. In their meta-analysis, Hanson and Morton-Bourgon (2009) identified three other unpublished studies examining the predictive accuracy of actuarial and adjusted actuarial risk ratings. In these studies, evaluators were asked to complete an actuarial risk tool and then were allowed to adjust the final risk score on the basis of factors that were not mentioned in the actuarial risk tool as part of their routine clinical assessment. In all three studies, the adjusted scores produced lower predictive accuracy than the unadjusted scores, suggesting the adjustment of actuarial risk estimates is not warranted except in the case of time spent offense-free (which itself is an actuarial adjustment).

Offender age is already incorporated into widely used actuarial risk measures, the Static-99R and Static-2002R, through adjusted offender age weights. Subjective adjustment of risk scores is not required. This may also be the case for other adjustment factors: If they receive sufficient empirical support, they can become part of the actuarial assessment measure; if they do not, then adjustment is not warranted.

COMBINING MULTIPLE RISK SCALES

In addition to clinically adjusting actuarial risk estimates, another seemingly common clinical practice is to score and combine multiple risk measures. Indeed, Doren (2002) suggested that multiple risk scales can be combined to increase predictive accuracy to the extent that the scales differentially assess atypical sexual interests and antisociality. For example, an evaluator might choose to combine the results from the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised, a relatively pure measure of psychopathic traits, and the Screening Scale for Pedophilic Interests as a relatively pure measure of pedophilic sexual arousal patterns. In their survey of risk evaluators, Jackson and Hess (2007) found that evaluators who used multiple risk measures tended to report each result independently rather than integrating the risk scores in some way, or tended to base their opinion on the highest risk score.

Decision Rules

Combining multiple risk scales seems reasonable because of the evidence that risk ratings for violence in the near future have a stronger relationship with that particular outcome when the raters agree (McNiel, Lam, & Binder, 2000). On the other hand, subjectively combining the results of multiple risk measures may recapitulate the problems associated with the traditional clinical approach of subjectively combining empirically identified risk factors (Grove et al., 2000; Kahneman, 2011). To address this question, I examined the impact of mechanically combining four actuarial risk scales—the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide, the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide, the RRASOR, and the Static-99—using three intuitive rules in a sample of 215 sex offenders (Seto, 2005). Two of these three rules were similar to medical rules that are used to combine the results of diagnostic tests (Gross, 1999; Politser, 1982). The first rule was Believe-the-Negative, which is to diagnose the disorder only if all the diagnostic tests are positive; in this context, all risk scales must exceed a given threshold to designate an offender as someone who is dangerous (i.e., as someone who is expected to sexually reoffend). The second rule was Believe-the-Positive, which is to diagnose the disorder if any one of the diagnostic tests is positive; in this context, consider an offender to be dangerous if any of the scales exceed a given threshold. The third rule was Average, that is, to average the results of the different risk scales, once they were transformed to the same metric, such that a relatively high score on one scale would be offset by a relatively low score on another scale.

These three rules represent combinations that are encountered in sex offender risk assessment. For example, Doren (2002) described a version of the Believe-the-Positive rule for combining risk scales that load differently onto the dimensions of antisociality and atypical sexual interests (Roberts, Doren, & Thornton, 2002). I also applied multiple logistic regression and principal components analysis to see if actuarial scales, or factors derived from these scales, could be combined using statistical optimization to yield greater predictive accuracy. In none of these analyses did combining scales provide a statistically significant or consistent advantage over the single actuarial risk scale producing the highest AUC for prediction of serious (nonsexually violent or sexual) or specifically sexual recidivism. This was the case whether the scale scores were combined using the Believe-the-Negative, Believe-the-Positive or Average rules, combined on the basis of relative rank (percentile score) in the sample or expected recidivism rates, or combined using statistical optimization methods. I concluded at that time that combining and interpreting the results of multiple actuarial risk scales when assessing the risk of sex offenders is inefficient because each additional risk scale takes time and effort to complete, and because apparently contradictory scores (e.g., one measure showing a high score with another measure showing a low score) is confusing to receivers of risk evaluations.

Barbaree, Langton, and Peacock (2006) reported that four different actuarial risk scales identified different subgroups of sex offenders as being higher in risk to reoffend. In other words, offenders identified as relatively high risk (based on their percentile rank) on one actuarial risk scale did not show the same rank on another scale. The difference in percentile rank was inversely related to the correlation between scale cores, so scales that were highly correlated with each other produced smaller discrepancies in percentile rank. Barbaree et al. (2006) suggested this finding justified scoring and interpreting multiple actuarial risk scales, to avoid confusion when different evaluators can arrive at different statements about an offender’s risk if they choose different actuarial risk scales. Barbaree et al. (2006) proposed that evaluators score multiple actuarial risk scales—although this does not improve predictive accuracy according to Seto (2005)—and then reconcile any discordant findings by describing how the different scales might differently load onto the risk dimensions of antisociality and atypical sexual interests (Barbaree et al., 2006; Roberts et al., 2002).

The Average Rule

More recently, Babchishin, Hanson, and Helmus (2012) found incremental validity even from combining three highly correlated risk measures—RRASOR, Static-99R, Static-2002R (correlations ranging from .70 to .92) in a meta-analysis comprising 20 samples and a total of 7,491 sex offenders. The average rule produced marginally better discrimination than choosing the highest score (see Believe-the-Positive), and better calibration than choosing either the lowest or highest score. Babchishin, Hanson, and Helmus (2012) suggested that combining multiple risk scales by averaging could be justified, contradicting my suggestion in Seto (2005) to pick the “best” scale rather than scoring multiple scales when considering discrimination alone. Lehmann et al. (2013) further examined this question in a study of three decision rules to combine the RRASOR, Static-99R, and Static-2002R in the risk evaluation of 940 adult male sex offenders followed for 9 years. Consistent with Babchishin, Hanson, and Helmus (2012), the evidence supported the result of averaging the risk ratios, as this produced good discrimination and calibration. Choosing the lowest risk result underestimated the likelihood of sexual recidivism, whereas choosing the highest risk result overestimated this likelihood. Given the newer evidence, maybe I was wrong in Seto (2005)

4

; averaging risk estimates from multiple risk scales has empirical support when calibration, not only discrimination, is also considered. On the other hand, I examined the impact of combining different risk scales, not variants within the same family of risk measures. The results obtained by Babchishin, Hanson, and Helmus (2012) and Lehmann et al. may partially reflect the impact of fine-tuning item weighting, greater reliability of measurement, and the power of very large samples.

Risk Hacking

Whether evaluators use single or multiple risk scales—but especially if they use single scales—the choice of risk measure should be made a priori, based on a review of independent validation evidence, the relevance of the measure to the offender population, and local policies. This is important to avoid what I call “risk hacking,” which involves the scoring of multiple risk scales but reporting only those that are favorable to the evaluator’s potential bias (e.g., as an expert called by the prosecution or by the defense) or subjective opinion (e.g., an intuition the individual is truly “low” or “high” risk). Similar to p-hacking, which involves post hoc decisions that distort results (e.g., conducting multiple statistical analyses but only reporting those that are favorable to the researcher’s position), post hoc reporting of results would distort the accuracy of risk evaluation (Head, Holman, Lanfear, Kahn, & Jennions, 2015). As with p-hacking, evaluation practices can have subtle tells that suggest risk hacking, such as the choice of different risk scales for similar clients or special explanations for why the standard or typical risk measure used in a practice or jurisdiction is not suitable.

OFFENDER TYPE SPECIFIC RISK ASSESSMENT?

The most widely used, validated risk measures were developed with mixed samples of sex offenders. It is possible that a specially developed risk scale could provide better performance for sex offenders against children, for example, by having child-victim-specific or pedophilia-specific items, such as phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children and having boy victims, multiple child victims, very young victims, and unrelated child victims. These items would be combined with general antisociality variables—offender age, criminal history, antisocial personality—that do so well in predicting recidivism in diverse offender groups, including mixed groups of sex offenders, indigenous sex offenders, female offenders, juvenile offenders, and offenders with mental disorders (Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Bonta et al., 2014; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998; Smith, Cullen, & Latessa, 2009).

Offender Types

Existing risk measures such as the Static-99 and Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide do well in subgroups of offenders distinguished according to victim age or relationship to victims (Bartosh, Garby, Lewis, & Gray, 2003; G. T. Harris et al., 2003). It is still possible, however, to specifically develop an actuarial risk scale for pedophilic sex offenders. Because the offenders would be homogeneous regarding pedophilia, I would expect antisociality variables to have much greater weight in any such scales. Similarly, developing a specific risk scale for psychopathic sex offenders would result in atypical sexual interest variables having much greater weight. Given the high predictive accuracies that can be obtained with excellent interrater reliability and no missing information, creating special scales for sex offenders with child victims may not be capable of yielding significantly greater accuracy. Having said that, we (Seto & Lalumière, 2001) inadvertently developed a risk scale for sex offenders with child victims when we developed the Screening Scale for Pedophilic Interests, a proxy measure for phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children (see

Chapter 2

, this volume). Both the original and revised versions of this measure also significantly predict sexual recidivism among men who have committed contact sexual offenses involving children (Helmus, Ó Ciardha, & Seto, 2015; Seto, Sandler, & Freeman, 2017).

Internet Offenders

In 2015, my colleague Angela Eke and I developed the Child Pornography Offender Risk Tool (CPORT) specifically for adult male child pornography offenders who may or may not have committed contact sexual offenses (Seto & Eke, 2015). Two CPORT items refer specifically to child-related content, and these items are unique compared with the sex offender risk measures I have discussed in this chapter, although they are related to the notion that interest in boys is a stronger predictor of sexual recidivism than interest in girls. The remaining items are very familiar, reflecting age, criminal history, violations of conditional release, and evidence of sexual interest in children. (For more information, see the CPORT Project Page:

https://www.researchgate.net/project/Child-Pornography-Offender-Risk-Tool-CPORT

.)

Returning to a point made in the Clinical Adjustments section, we (Seto & Eke, 2015) considered many other variables for the CPORT, some of which have intuitive appeal as factors that should be considered, including whether the child pornography offender lived with or worked with children, duration and amount of child pornography collecting, ages of depicted children, and whether the offender also had other pornography depicting paraphilic themes. Two small validation studies have been conducted so far, one by us with a small sample of child pornography offenders that found scores predicted sexual recidivism, as expected (Eke, Helmus, & Seto, 2018), and an independent cross-validation by Pilon (2016), who found a version of the CPORT—modified scoring, minus the two child content items—predicted general recidivism among 279 child pornography offenders who had been in provincial custody in Ontario and were followed for an average of 3.2 years: 7 (2.5%) committed a new child pornography offense and 2.9% committed a new sexual offense, which could include child pornography recidivism, defined as reentry into provincial corrections (i.e., new offenses resulting in federal sentences of 2 years or longer, or sentences in other provinces, were not captured).

It is also worth pointing out that modified versions of existing risk measures are likely to be effective in assessing child pornography offender risk for sexual recidivism. Wakeling, Howard, and Barnett (2011) found that a modified Risk Matrix 2000, the standard sex offender risk measure used in the UK prison system, significantly predicted sexual recidivism among online sex offenders followed for 2 years. I expect the same would be true for modified versions of the Static-99R or other validated actuarial risk scales developed for contact offenders, although the expected recidivism rates would likely be higher than observed rates.

Generalizability

As already noted, most of the risk assessment research has been conducted on adult male offenders, although several measures have some empirical support for use with juveniles who have sexually offended (e.g., JSOAP-II or ERASOR-2; see Viljoen, Mordell, & Beneteau, 2012). The low sexual recidivism rates reported by Caldwell (2016) suggest that it would be difficult to demonstrate predictive accuracy without very large samples followed for a long time. Similarly, the very low sexual recidivism rates of adult female sex offenders (median of 1.5% after 6 years in Cortoni, Hanson, & Coache, 2010) suggests an empirically validated risk measure for female sex offenders will be a long time coming, as it will take very large samples followed for longer periods of time to statistically produce discrimination and to then evaluate calibration.

It is not a given that risk tools developed for adult men who have sexually offended will generalize to women, although it is true that men and women share many major risk factors in terms of general offenders and the risk of any recidivism (Smith et al., 2009). As discussed in

Chapter 2

, female and male sex offenders differ in important ways—for example, pedophilia is much less common among female offenders—which would be expected to translate to differences in offense motivations, offending processes, and risk to reoffend.

What about other sex offender subgroups, such as individuals with developmental disabilities, mental disorder, or different ethnicity groups? For individuals with developmental disabilities, the results of a cumulative meta-analysis suggest that the Static-99/R is valid for this group. Hanson, Sheahan, and VanZuylen (2013) found that the Static-99 performed as intended in a cumulative sample of developmentally disabled sex offenders, thus leading to a recommendation to use the Static-99R with these cases (

http://www.sexual-offender-treatment.org/119.html

). For mental disorders, the development research on the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide was conducted using a sample comprised of mentally disordered sex offenders seen in a psychiatric setting and sex offenders referred from the criminal justice system. The predictive accuracy was good for both groups (G. T. Harris, Rice, Quinsey, & Cormier, 2015).

Generalizability across ethnicity is more complicated. Leguízamo, Lee, Jeglic, and Calkins (2017) examined the predictive validity of the Static-99R with 483 Latino offenders and found that this measure significantly predicted recidivism for American-born Latino and Puerto Rican offenders but not for Latino immigrant offenders, suggesting culture is a relevant moderator. On the other hand, other studies suggest that risk measures can generalize across ethnicity groups, including studies demonstrating risk measures predict recidivism among adolescents who have sexually offended in Singapore, European adult offenders, and among both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal adult offenders in Canada (e.g., Babchishin, Blais, & Helmus, 2012; Chu, Ng, Fong, & Teoh, 2012; Lehmann et al., 2013; Olver et al., 2016). This is an important avenue to continue because to explore as risk measures are adopted in multi-cultural societies and internationally.

RISK COMMUNICATION

The sex offender risk assessment field is maturing, with growing consensus about the empirical support for using actuarial or structured risk measures, assessment of dynamic risk, and interpreting risk assessment results in terms of combining results, considering calibration, and the generalizability of risk tools. An emerging area now is how to best communicate information about risk to decision-makers. Sex offender risk assessments, no matter how reliable and valid they can become, will not have the desired impact on public safety and offender outcomes if decisions about sentencing, institutional placement, treatment, and supervision are not correctly informed by risk assessment results.

Method

Two studies—Hanson, Lloyd, Helmus, and Thornton (2012) and Scurich, Monahan, and John (2012)—demonstrate that reporting risk results in terms of raw scores and statistics can be confusing, especially for decision-makers who are less numerate. Recognizing this challenge, Babchishin and Hanson (2009) suggested that risk communication could be improved by explicitly linking risk categories with numbers as well as graphs. Their example illustrations included a risk “thermometer” that represented an offender’s percentile rank among similar offenders. Others have suggested histograms, icon arrays, or pie charts as ways of illustrating information about relative risk and probability of recidivism (G. T. Harris, Rice, Quinsey, & Cormier, 2015; Hilton, Harris, & Rice, 2010).

The use of visual representations has been recommended to improve risk communication in other practice areas, such as health, for example, in illustrating the proportion of a population that is at risk for a particular condition. The impact of these visualizations on violence risk decision making is unclear. In one study, Hilton, Carter, Harris, and Sharpe (2008) gave participants brief case descriptions that varied in whether they had a numerical probability statement and whether they also had a nonnumerical risk category label (e.g., “high risk”). Participants assigned a higher level of security to cases with the higher actuarial risk score when the risk result was stated—particularly as a probability of recidivism rather than a frequency—whereas adding the categorical label did not have this effect. Using a similar study design with three different risk levels, Scurich et al. (2012) found the desired distinction in assigned security levels.

Influencing Decision Making

A related issue is how risk information should be incorporated into decisions about sentences, institutional placements, treatment assignment, and titration of supervision. In a general forensic context, Hilton and Simmons (2001) found that tribunal decisions about release to a lower level of security were unrelated to actuarially estimated risk of future violence. The strongest predictor, by far, was the senior clinician’s testimony, which in turn was related to institutional behavior problems, less medication compliance and response, more serious criminal history, and lower physical attractiveness. Analyzing data on subsequent tribunal decisions for the same institution, McKee, Harris and Rice (2007) found the situation had improved. Tribunal decision was still highly correlated with psychiatrist testimony and clinical team recommendation, but both testimony and team recommendation were related to insight into illness, medication noncompliance, patient request for transfer to lower security, and actuarially estimated risk for future violence, in that order. Although encouraging, these results suggest there is still a lot of room for improvement.

In Hilton et al. (2017), we examined the impact of four different types of graphs in the security recommendations of university students given case descriptions for two offenders who differed by one risk category on the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide. Effective decision making was defined in this study as the actuarially higher risk offender being assigned to greater security than the lower risk offender. The graph resulting in the largest distinction among less numerate students was a probability bar graph. We then tested this probability bar graph with 54 forensic clinicians in a second study. The graph had no overall effect. Among more experienced staff, however, decisions were unrelated to actuarial risk in the absence of the graph and in the desired direction with the addition of the graph.

Lehmann, Thornton, Helmus, and Hanson (2016) discussed different options for reporting risk, including percentile rank, risk ratios relative to a reference group, and absolute recidivism rates for the Risk Matrix 2000, in a cumulative sample of over 3,000 sex offenders. Most reporting of psychological test results is norm-based, that is, the key information being conveyed is relative rank (e.g., percentile rank, relative risk ratio). But sometimes the key information to be conveyed in the appraisal of likelihood of sexual recidivism is criterion-based rather than norm-based: How likely is this person or group of persons to reoffend? Results suggested relative ranking is robust, with each increase in risk category on the Risk Matrix 2000 (four categories) associated with an approximate doubling of risk.

Standardized Risk Categories

Hanson, Babchishin, Helmus, Thornton, and Phenix (2017) argued for the development and adoption of a nonarbitrary, criterion-referenced metric across risk measures that otherwise differ in their ranges of possible scores, number of risk categories, risk labels, and probabilities of recidivism attached to those categories. They proposed a five-category system, each associated with a typical risk/need profile and clinically meaningful trajectory. Category I offenders (very low risk) were exclusively older individuals (over 60) who were first-time offenders against an acquaintance or family member, usually a child. They had very few if any risk factors and were very unlikely to reoffend, even without any intervention. Category II (below average risk) were younger (mean age of 50) but still older than the average offender (mean age of 40). Forty percent had a prior criminal history, but it was rare to have a prior sexual offense or stranger victims; the majority had offended against children and they had a few risk factors that could be addressed through brief interventions. Category III (average risk) were more likely to have prior criminal history but still unlikely to have prior sexual offenses or stranger victims. This category was a mixture of offenders against children and offenders against adults. They had more problems and would require more intensive intervention to reduce their likelihood to a lower level. Category IV-a (above average risk) were slightly younger and likely (90%) to have a prior criminal history. Thirty percent had a prior sexual conviction, and half had offended against strangers. Two thirds of this group had offended against adults. Category IV-b (well above average risk) was the highest risk group identified. Most had a prior criminal history, most had prior sexual convictions, and most had offended against strangers. The most conservative management strategy would be required for this fifth risk group.

PREDICTING ONSET OF SEXUAL OFFENDING

The research reviewed in this chapter so far has focused on the risk of future offenses among persons who are already known to have committed a sexual offense. In other words, the actuarial and structured risk scales that have been developed predict the persistence of sexual offending (recidivism). Much less is known about the factors that predict whether someone with no known history of sexual offending will commit a first sexual offense. How then can individuals who are at risk of committing sexual offenses against a child for the first time be identified?

Among General Offenders

As noted in

Chapter 3

, Duwe (2012) identified a set of factors (most representing aspects of criminal history, as a result of the sample and how data were collected) that predicted first-time conviction for a sexual offense within 4 years of opportunity in a large sample of general offenders released from prison in Minnesota. The sexual conviction rate was low for the subset with scores on a general measure of criminogenic risks and needs, the Level of Supervision Inventory (77 of 6,523, or 1.2%); Duwe did not report the sexual conviction rate for the overall sample (although inferring from Table 4 in Duwe, it is 1.1%) or the proportion specifically involving offenses against children, as opposed to offenses against adolescents or adults or involving noncontact offenses. Langan, Schmitt, and Durose (2003) found a similar sexual offending rate of 1.3% following 262,420 non–sex offenders over a 3-year period postprison release. Presumably, most of any sexual offenses that will occur are committed in the first few years, because Hanson and Scott (1995) found only a slightly higher sexual offending rate of 2% of their group of non–sex offenders during the follow-up period of 15 to 30 years.

This baseline rate among individuals involved in the criminal justice system is not markedly different from the general population of men. P. Marshall (1997) analyzed data from the United Kingdom and found that one in 90 men born in 1953 had a conviction by the age of 40 for a sexual offense involving contact with a victim, which included attempts to have sexual contact with a victim but excluded convictions for noncontact sexual offenses such as indecent exposure or pornography; the majority of these sexual offenses involved a minor. It should be noted that general population estimates would not account for the role of criminal involvement; one could assume that some of the sexual offenses observed by P. Marshall involved those with a prior criminal history.

In terms of the general population, Babchishin et al. (2017) found that the base rate for any sexual offense conviction (not only those involving children) for Swedish males ages 15 or older (15 is the age of criminal responsibility in Sweden) was 0.5% for a 1973–2009 cohort. As discussed in

Chapter 1

, Ahlers et al. (2011) surveyed 367 German men and found 4% had engaged in sexual behavior with children. Seto et al. (2010) found 4% of young Swedish men admitted to viewing pornography depicting adult–child sex. Dombert et al. (2016) found 2.5% of a large sample of German men admitted viewing child pornography and 3.2% admitted to contact sexual offenses against children. Other convenience sample studies were reported in

Table 1.3

in the first chapter of this volume. It is hard to compare estimates, given the many factors that can influence sexual arrest and conviction rates across jurisdictions and times, including differences in reporting, law, and law enforcement. Nonetheless, it is interesting to speculate that criminal justice involvement elevates the likelihood of onset of sexual offending, just as one might expect having pedophilia or hebephilia would (in line with the theories of sexual offending reviewed in

Chapter 4

).

Among At-Risk Individuals

Rabinowitz Greenberg, Firestone, Bradford, and Greenberg (2002) followed a sample of 221 men who had been criminally charged for noncontact sexual offending and who met diagnostic criteria for exhibitionism. None of these offenders were known to have committed a contact sexual offense at the time they were assessed. Nonetheless, among this group of exhibitionistic sex offenders, phallometrically assessed sexual arousal to children distinguished those who subsequently committed contact sexual offenses from those who committed noncontact sexual offenses again during the average follow-up period of almost 7 years. Fourteen men committed a contact sexual offense, and 27 committed another noncontact sexual offense during the follow-up period. The authors did not distinguish further between sexual offenses involving children and those involving adults; my hypothesis would be that arousal to children is more strongly related to new sexual offenses against children. Other studies also suggest that some exhibitionistic offenders go on to commit sexual offenses against children (Gebhard, Gagnon, Pomeroy, & Christenson, 1965; Rooth, 1973). This “crossover” in offending is not unusual; other studies find that substantial proportions of exhibitionistic offenders have sexually offended against children, and some men who sexually offend against adults also have child victims as well (e.g., Abel et al., 1988; Stephens, Seto, Goodwill, & Cantor, 2018; Sugarman, Dumughn, Saad, Hinder, & Bluglass, 1994; Weinrott & Saylor, 1991).

Focusing on another population of men who might pose a risk of sexually offending against children directly, we followed a sample of 541 men convicted of child pornography offenses for an average of 4 years. Whether a child pornography offender committed a new contact sexual offense was related to whether they had a history of violent offending, which could include both nonsexually violent and contact sexual offending. Whether a child pornography offender committed a new sexual offense of any kind was related to having any other criminal history; the subset of 228 child-pornography-only offenders had the lowest contact sexual and child pornography recidivism rates, at 1.3% and 4.4%, respectively. All the recidivism studies followed men who were already known to the criminal justice system. They did not directly address the question of risk among individuals with no known criminal record who might pose a risk to sexually offend against children.

In the General Population

Consistent with the motivation-facilitation and other models of onset of sexual offending, I would predict that men in the general population who are both pedophilic or hebephilic (motivation) and antisocial (facilitation) are the most at risk of committing sexual offenses involving children. The strengths of motivation or facilitation factors influence each other: Individuals with pedophilia and a very high sex drive, for example, may act with a lower level of antisociality; individuals who are highly antisocial may not have pedophilia or hebephilia at all, offending opportunistically. Child victims would differ based on levels of motivation and facilitation: Pedophilic individuals would target prepubescent boys or girls whereas antisocial, nonpedophilic individuals would target older girls.

We know that opportunity and access to potential victims should matter, in line with general criminological understanding of how opportunity is related to crime. The logic of situational crime prevention is that situational and environmental factors can influence the likelihood or extent of criminal behavior. For example, LeClerc, Smallbone, and Wortley (2015) found that the presence of a guardian (e.g., another adult) reduced the severity of sexual offenses that took place. I have already noted the role of opportunity in incest offending, where related perpetrators can have high degrees of access to potential child victims. Similarly, Babchishin et al. (2015) found that online offenders had more access to the Internet compared with contact offenders, whereas contact offenders had more access to children compared with online offenders.

Relatively little work has been done on individuals who have greater opportunity to offend against children because of employment or volunteerism. One can presume that most people who work with children do so for good reasons. However, this group might be of special concern because some individuals who are sexually or romantically attracted to children might purposefully seek jobs involving children. Past studies have found that individuals who sexually offended against children through work differ from other offenders against children by being older, better educated, and less likely to have an adult romantic relationship (Colton, Roberts, & Vanstone, 2010; Sullivan & Beech, 2004; Turner, Rettenberger, et al., 2016). Turner, Rettenberger, et al. (2016) also found that offenders who knew their child victims through work were more likely to show indicators of pedophilia while showing fewer indicators of antisociality, such as antisocial behavior or alcohol use problems (see also Langevin, Curnoe, & Bain, 2000; Parkinson, Oates, & Jayakody, 2012; Spröber et al., 2014; Sullivan, Beech, Craig, & Gannon, 2011). This makes sense inasmuch as any preemployment screening for individuals who work with children will focus on antisociality in the form of criminal records or other background checks.

As it turns out, simply seeking or volunteering to work with children has relatively little impact on the likelihood of sexual offending compared with other factors: Working with children was not a significant risk factor among individuals convicted of child pornography offending, although it did relate to having sexual interest in children (Seto & Eke, 2015, 2017). Turner, Hoyer, Schmidt, Klein, and Briken, (2016) reanalyzed data from the Dombert et al. (2016) survey of over 8,000 German men and found that working with children was associated with self-reported sexual contacts with children, but it only explained 3% of the variance. In the retrospective, cross-sectional study by Turner, Hoyer, et al., results were consistent with the motivation–facilitation model: The 37 men who worked with children under age 13 and who admitted sexually offending against a child were more pedohebephilic (viewed child pornography, admitted sexual fantasies about children, considered child sex tourism), more antisocial (prior convictions for nonsexual offenses), and higher in sex drive (thinking about sex, using pornography daily) than the 816 men who worked with children and denied any sexual offenses against children. These factors accounted for about a third of the variance in self-reported sexual contacts with children. To illustrate the prevalence of sexual interest in children, 70% of the men who offended against children through work admitted to sexual fantasies about children, 51% had viewed child pornography, and 46% were interested in child sex tourism. This can be compared with those who worked with children but denied any sexual offenses against children: 4% admitted having sexual fantasies about children, mostly about girls, 2% admitted viewing child pornography, and none were interested in child sex tourism. Whether someone had been detected was related to history of childhood sexual abuse, more prior nonsexual offense convictions, higher self-rated likelihood of offending against children in the future, and more likely to have paid children for sex. No significant group difference in sex drive was found.

PROTECTIVE FACTORS

Interest is building in the inclusion of protective factors, as well as risk factors, in the assessment of sex offenders. Protective factors help reduce the likelihood of sexual recidivism and can be conceptualized as individual strengths that can mitigate or even counteract risk factors; de Vries Robbé, de Vogel, Koster, and Bogaerts (2015) suggested potential protective factors as the opposite of known risk factors. For example, effective problem-solving skills and strong social supports could reduce the likelihood of sexual offending. In principle, protective factors could offset the risk contributed by factors in different domains. For example, returning to the motivation–facilitation model, someone who has a lot of prosocial support and who has prosocial attitudes and beliefs may be protected from the risk they would otherwise have as a result of their excessive sexual preoccupation or sexual interest in children.

There is less empirical work on the potential contribution of protective factors, but that is beginning to change as measures are developed. These include the Structured Assessment of Protective Factors (SAPROF; de Vogel, de Vries Robbé, de Ruiter, & Bouman, 2011) for violence assessment, and the Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability (START; Nicholls et al., 2006). The January 2015 issue of

Sexual Abuse

5

focused on the assessment of protective factors in adolescents or adults who have sexually offended. In a sample of 83 contact sex offenders, de Vries Robbé et al. (2015) found that SAPROF scores were negatively related to two risk measures, the sex-offender-specific SVR-20 and the more general forensic HCR-20. Moreover, SAPROF scores predicted recidivism even after statistically accounting for scores on the two risk measures. In contrast, Zeng, Chu, Koh, and Teoh (2015) also found that SAPROF scores were negatively related to the ERASOR, a structured risk assessment for juveniles who have sexually offended, but SAPROF scores were not predictive of recidivism in their sample of 97 Singaporean youth who had sexually offended. Two other studies suggested that protective factors could contribute to the assessment of recidivism potential in youth who had sexually offended (Spice, Viljoen, Latzman, Scalora, & Ullman, 2013; van der Put & Asscher, 2015).

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Sex offender risk assessment has advanced a lot in the past 30 years, with the development and dissemination of actuarial risk scales to predict recidivism. Cross-validation studies support the reliability and predictive validity of these scales, although recent studies have examined cohort effects in recidivism rates and have addressed debates about discrimination and calibration (e.g., Helmus et al., 2012). Nonetheless, the use of actuarial risk scales is increasingly common, especially in high-stakes assessments, such as dangerous offender hearings in Canada and sex offender civil commitment proceedings in the United States (Jackson & Hess, 2007). In the 2014 version of the practice guidelines for members of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers Guideline 6.02 states,

Members conducting risk assessments of sexual abusers use empirically–supported instruments and methods (i.e., validated actuarial risk assessment tools and structured, empirically guided risk assessment protocols) over unstructured clinical judgment. (p. 25)

In the first edition of this book, I was excited about the “actuarial revolution” in sex offender risk assessment and hoped it would spread to other sex offender populations (female sex offenders, juvenile sex offenders), other offenders, and then to other areas of forensic and clinical practice. Some progress has been made on these fronts, including the advent of structured checklists to assess risk for depression or cardiovascular disease, structured checklists to avoid surgical and other medical errors (see Gawande, 2009), and the increasing power and ubiquity of algorithms in optimizing online functions in search, social networks, and retail.

On the other hand, actuarial risk assessment has been met with some resistance in the form of new structured risk assessment tools and critiques of well-validated measures, such as Static-99R, because absolute recidivism rates vary. Unstructured clinical judgment, either on its own or to adjust actuarial estimates of risk to reoffend, is still not empirically supported practice. More work is needed on dynamic risk assessment and how to best communicate risk to decision makers. A wide-open territory for empirical exploration is the development of risk assessments for individuals who have not committed sexual offenses against children, as far as is known, but who represent a concern. This includes nonoffending persons with pedophilia and noncontact sex offenders (e.g., child pornography, exhibitionism, voyeurism). A huge boon for child protection would be a brief, relatively inexpensive screening tool that could be used for individuals wanting to work with children or youth, such as teachers, child care workers, coaches, and volunteers for youth-serving organizations. But once higher risk individuals have been identified, what can be done to reduce the likelihood that children will be sexually exploited or abused? I review and discuss interventions in the

next chapter

.

1

Most new offenses take place within the first few years of opportunity, although some do reoffend many years later (Hanson, Scott, & Steffy, 1995). As discussed later, time spent offense-free in the community also has an effect that adds to what is known about the likelihood of sexual recidivism based on personal characteristics (Blumstein & Nakamura, 2009; Hanson, Harris, Helmus, & Thornton, 2014).

2

Some clinicians and researchers have pointed out some factors can be organized under a third dimension comprising interpersonal deficits, such as poor social skills, social isolation, and limited or no social support. This dimension is not as strongly or consistently associated with sexual recidivism as atypical sexual interests or antisociality (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004, 2005).

3

My preference is for actuarial approaches because I think mechanical risk assessment minimizes the risk of evaluator biases and of degradation of accuracy from unstructured subjective judgment. This is consistent with the findings of Hanson et al. (2009), which found that actuarial measures produced higher accuracies, on average. I would encourage the use of structured processes to incorporate information about dynamic risk factors and decisions about intervention such as treatment or supervision. Having said that, I understand that structured professional judgment measures seem to be more palatable to evaluators and decision-makers, and I would still prefer a valid risk assessment over the perils of unstructured opinion.

4

This is not the first time I have been wrong, and it certainly will not be the last time either!

5

Transparency: I am now editor-in-chief of this journal, although the articles that appeared in this issue were handled by the former editor-in-chief, James Cantor.