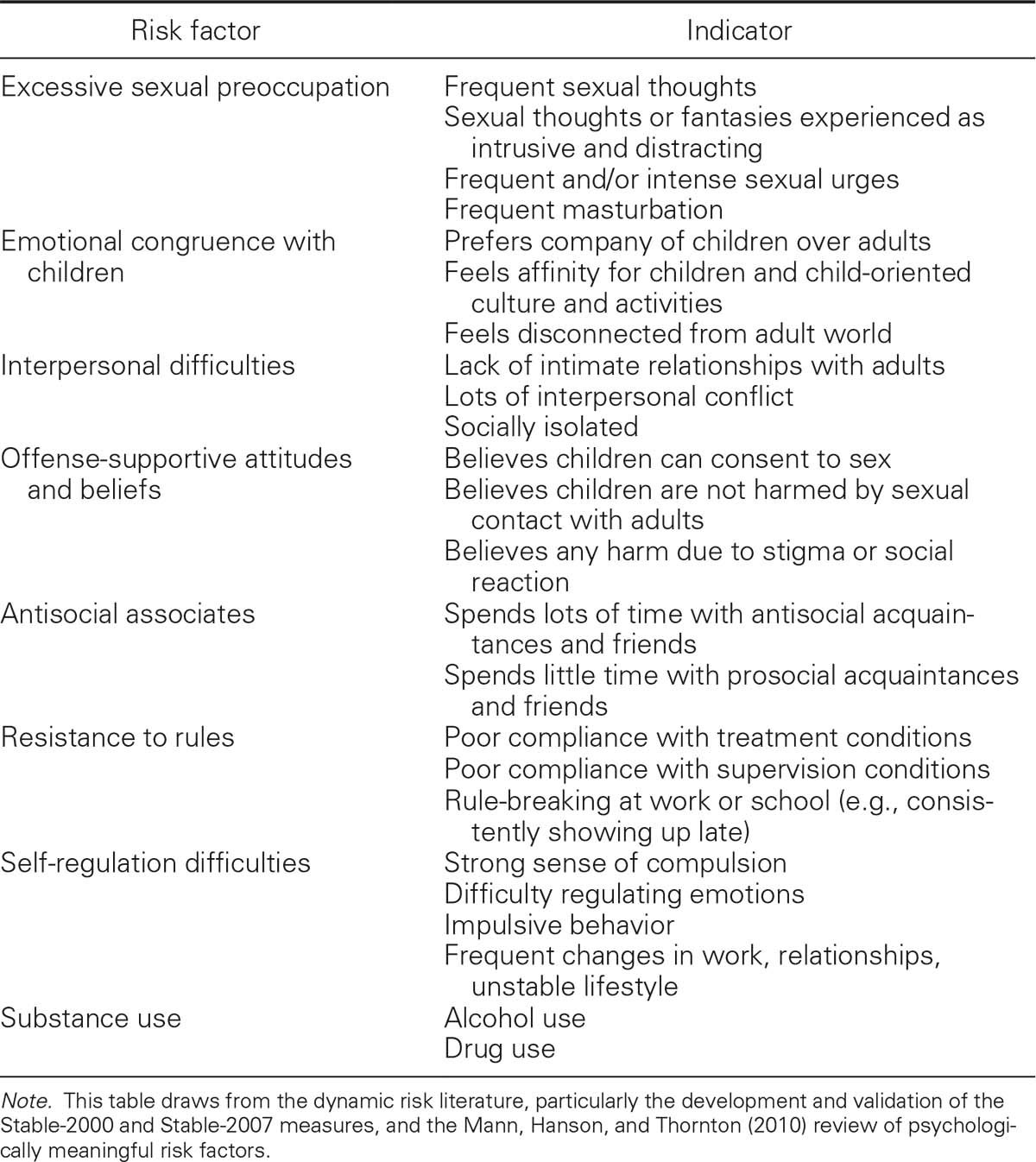

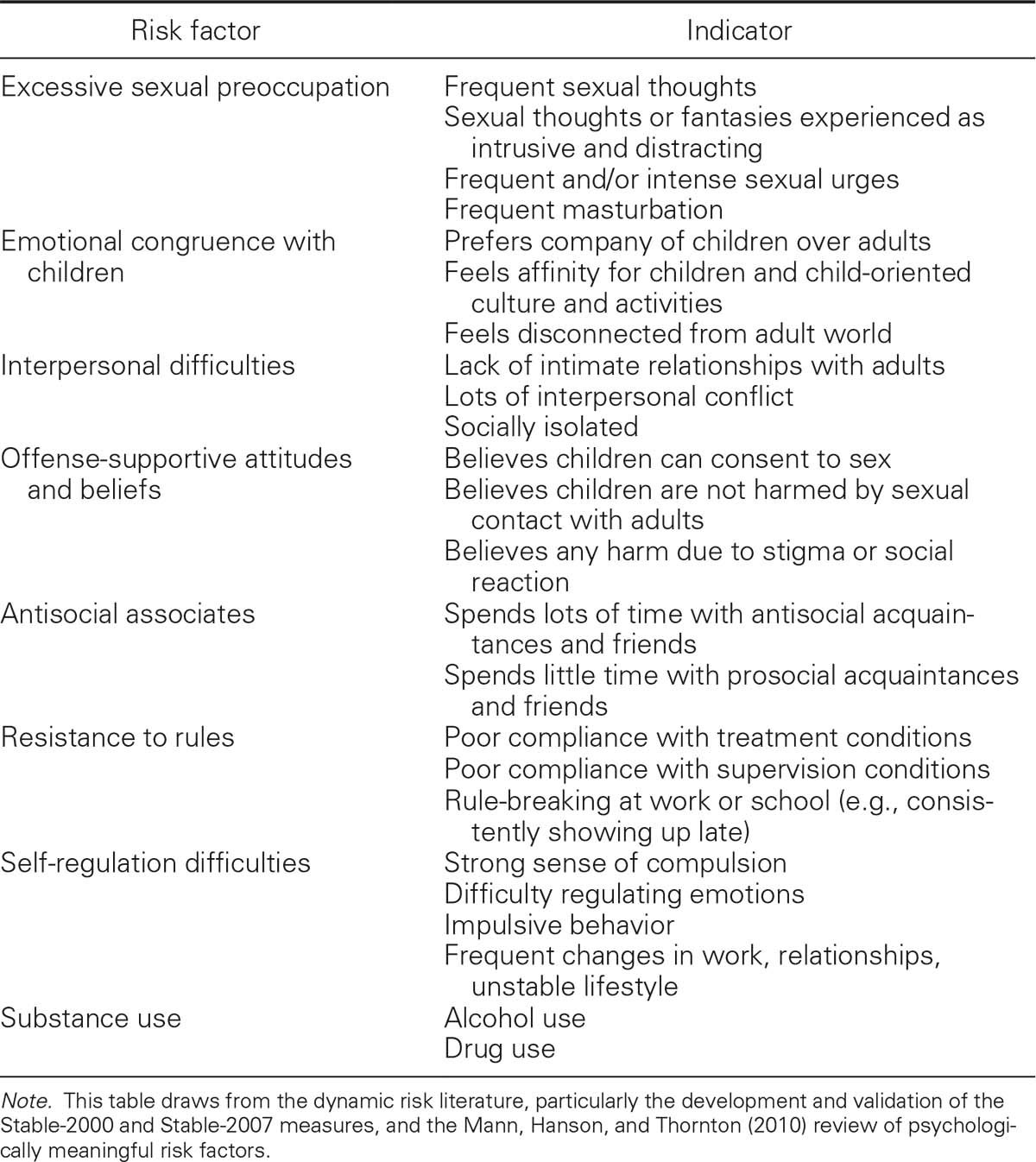

TABLE 8.2

Examples of Dynamic Risk Factors and Some Corresponding Indicators

This kind of proximal outcome research could advance both the knowledge of the causes of sexual offending and the likely components of effective sex offender treatment. For example, finding that social skills deficits and treatment performance in social skills training—level of participation, compliance with training requirements, and actual change in social skills—predicts sex offender recidivism would suggest that social skills deficits are one of the causes of sexual reoffending and would suggest that social skills training should be part of sex offender treatment. Of course, demonstrating such a relationship is a necessary but not sufficient condition. Failing to find this relationship, on the other hand, would indicate that social skills deficits are probably not causally related to sexual reoffending, and would indicate that other targets should be the focus of treatment.

A distinction between onset versus persistence factors could be valuable in pursuing this research. Factors that are associated with the likelihood of initially committing a sexual offense (onset) might not be predictive of recidivism (persistence), and vice versa. For example, we have found that sex offenders are more likely to have been sexually abused than non–sex offenders in both adolescent and adult samples (Jespersen, Lalumière, & Seto, 2009; Seto & Lalumière, 2010). However, a history of sexual abuse is not predictive of recidivism among sex offenders (Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2004). This suggests that sexual abuse may be an onset, but not persistence factor in, sexual offending. Some sex offender treatment programs attempt to address sexual abuse history as part of trauma-informed care, but this is less likely to have an impact on recidivism than focusing on persistence factors, such as antisocial attitudes and beliefs, substance abuse, and self-regulation problems (Hanson & Harris, 2000). In contrast, programs that attempt to prevent child sexual abuse could reduce the onset of sexual offending as the children grow up.

Treatment Attrition

Strong evidence indicates that offenders who drop out or refuse treatment are more likely to offend than those who complete treatment (Hanson et al., 2002; Lösel & Schmucker, 2005; Marques et al., 2005). In the Hanson et al. (2002) meta-analysis, the difference in recidivism between treatment dropouts and treatment completers was larger than the difference between offenders in the treatment and comparison conditions. Treatment completion is associated with individual characteristics such as motivation, ability, willingness to comply, impulsivity, hostility, and other antisocial tendencies that are associated with risk to reoffend (e.g., Craissati & Beech, 2001; Moore, Bergman, & Knox, 1999). Evaluation studies that do not take attrition into account (e.g., by excluding treatment dropouts in their group comparisons or by comparing treatment completers with individuals who drop out or refuse treatment) will bias their results toward treatment appearing to be more effective than it is.

As an illustration, a hypothetical sex offender treatment program that required typical English-speaking sex offenders to learn to speak Mandarin, play a musical instrument like a virtuoso, and master calculus could show a positive treatment effect if it compared treatment completers to dropouts or refusers, not because speaking a new language, playing a musical instrument, or learning calculus helps prevent sexual offending, but because the treatment completion group is likely to be more motivated, intelligent, compliant, and capable of learning new skills than those who refused or dropped out. In this vein, sex offenders who dropped out of the Hucker et al. (1988) randomized clinical trial examining the impact of antiandrogens on sexual response reported more frequent sexual fantasies about children; excluding these offenders would make the treated group look like it had improved, when there might in fact have been no difference between the treated and comparison groups. The need to take treatment attrition into account is recognized in treatment evaluation, represented by recommendations to evaluate the treatment as planned, as well as intent-to-treat groups (e.g., Chambless & Hollon, 1998).

The SOTEP program dealt with the problem of treatment attrition in several ways. The authors did not terminate treatment participants who did not make progress or were disruptive in minor ways. Only those who created severe management problems (e.g., committed assaults, interfered with the treatment of other offenders, committed serious contraband violations) were terminated from treatment. Those who voluntarily withdrew from treatment were given 24 hours to reconsider their decision. A decision was made early during the SOTEP project to include those who were in treatment for at least 1 year (half of the 2-year program) in the treatment group for the follow-up analyses. Finally, to deal with the problem of eligible participants who changed their minds before admission to the program, a change in protocol was made after the 4th year of the project so that prospective treatment participants were not matched to controls until the treatment participant was transferred to the hospital.

Program Fidelity

Another general principle in the intervention literature is the importance of high program fidelity in dissemination, implementation, and service delivery (see Stirman, Crits-Christoph, & DeRubeis, 2004). In other words, the treatment that is delivered should correspond to the treatment that is intended, in terms of format, content, intensity, and targets. This principle is highlighted in results of randomized clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of multisystemic therapy for delinquent juveniles, for which high fidelity to the treatment model and techniques is associated with stronger outcomes (see Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998). In contrast, low program fidelity can dilute the treatment program to the point that it no longer has a significant effect on the desired outcomes (see Moncher & Prinz, 1991). Lower treatment fidelity may explain the typical decline in effect sizes obtained in replication studies and in “knowledge transfer” studies, because original evaluations are often completed in academic or research institutes following strict protocols, manualization, and extensive staff training, whereas real-world implementations often have to deal with administrative, staff, and client pressures to modify the treatment protocol, varying levels of staff training as new staff join the team, and “drift” over time as staff apply the protocol (e.g., by bringing in other techniques from their previous treatment experience). One plausible interpretation of Lösel and Schmucker’s (2005) finding that evaluations reported by authors affiliated with the treatment program produced larger effect sizes than evaluations reported by nonaffiliated authors is that the former group were able to increase program fidelity by their involvement. (An alternative, and also plausible, explanation is that nonaffiliated authors were more willing to report smaller effect sizes than affiliated authors, showing an allegiance effect as mentioned in the

previous chapter

for evaluations of risk measures.)

CHAPTER SUMMARY

This chapter has identified many questions about the effective treatment and management of persons with pedophilia and sex offenders against children. These questions include the irrelevance of common treatment targets, such as acceptance of responsibility and expressions of remorse and victim empathy; whether changes in pedophilic sexual arousal because of behavioral conditioning or antiandrogen treatment translate to long-term changes in sexual behavior involving children; and the relative importance of general versus specific treatments for pedophilic sexual offending. Methodologically rigorous evaluations are needed to answer these important questions, and theoretically informed treatment models that draw from general offender intervention research and specific research on pedophilia are needed to develop empirically supported treatments to reduce child sexual abuse.

Until the results of such research are available, how should clinicians proceed? I believe a conservative approach is warranted, guided by the scientific knowledge that is available. Based on the research reviewed here, some recommendations are summarized in

Table 8.1

and

Exhibit 8.1

. Intervention for sex offenders should be preceded by an actuarial or structured risk assessment, to prioritize cases according to risk to reoffend and to guide subsequent decisions. For sex offenders against children, the options range from minimal intervention for the lowest risk individuals to long-term incapacitation for the highest risk individuals. The clinician should also monitor potentially worrisome behaviors, such as access to child pornography, unsupervised contacts with children, and alcohol or drug consumption that leads to disinhibition of behavior (e.g., Abracen, Looman, & Anderson, 2000). Ongoing assessment with validated dynamic risk measures is needed to monitor changes in imminent risk. Clinicians and other professionals should rely on sources of information other than self-report whenever possible.