I have terrible news to tell you …

Private Houseman, 2/24th Regiment

Chelmsford's return to Isandlwana

January 22 began frustratingly for Chelmsford's force, including four companies of the 2/24th who found themselves chasing elusive groups of Zulus. As the morning wore on, disquieting messages began to reach Chelmsford's staff officers that there might be a problem at Isandlwana. As early as 9.30 am a message was received from Pulleine that the Zulus were advancing towards the camp. A junior staff officer, Lieutenant Berkley Milne RN, was dispatched to a nearby hilltop with his telescope; he saw nothing amiss. Chelmsford then set off to scout the area between Magogo Hill and the Mangani waterfall. Accompanied only by a small escort, he did not think it prudent to inform his staff officers of his whereabouts, and when subsequent messages arrived from Isandlwana, Chelmsford could not be found until 12.30 pm. Distant firing could now be heard from the direction of Isandlwana, so Chelmsford and his staff rode to the top of a nearby hill and observed the camp through field glasses. Nothing untoward could be seen, partly because of the thick heat haze and because the battle at the camp was taking place inside a long valley. Chelmsford assumed that any Zulus there had long been rebuffed, but he nevertheless decided to ride back towards the camp, leaving Glyn to concentrate the force and organise the new campsite near Mangeni, a location considered by Chelmsford to be ideal as a bivouac site for the night

Colonel Arthur Harness RA was with the guns that accompanied Chelmsford's force, and during the morning he heard gunfire from the camp and realized that Isandlwana was probably under serious attack. He spontaneously ordered those under his command to march back to the camp. His force had only travelled a mile and a half when a message from Chelmsford ordered him to about-turn to the new campsite. Meanwhile, Russell arrived on the scene and informed Chelmsford that a message had arrived to the effect that Durnford was also engaging the Zulus. An uneasy Chelmsford and his staff set off towards the camp to ascertain the situation. After a few miles they came across Commandant George Hamilton-Browne's battalion observing the camp; Chelmsford again ordered Hamilton-Browne to advance just as Commandant Rupert Lonsdale arrived to report that the camp had been lost. Lonsdale had ridden back to the camp having suffered from a fall and sunstroke; as he approached the camp in a dazed state he suddenly realised it was in Zulu hands. Only two hundred yards from the camp he turned and, riding for his life, escaped across the plain towards Chelmsford's force. Based on hearsay, much has been erroneously written about Lonsdale's injury. Harford's recently discovered letters mention the incident and he puts the record straight:

It was now nearing the 11th January, the date fixed for the troops to move across the border. Lord Chelmsford had arrived at Rorke's Drift and Lonsdale rode over to have an interview with him but received no definite orders with regard to the movements of the Contingent. However, one morning I had occasion to go to Rorke's Drift myself, to see the Adjutant-General, Major Clery. Luckily, arriving at a very early hour, and having completed my work with him, I was on the point of mounting my pony to ride back to camp, when Major Clery said, “You will have everything ready, Harford, won't you, for the General today?” “Good Heavens, Major”, I said, “This is the first I've heard about his coming!” “You don't mean to say that Lonsdale never told you about it?” he replied, “He is going to inspect you at twelve o'clock. The General gave Lonsdale his orders days ago.”

Well, I rode off as hard as I could go, to camp. I found Lonsdale sitting in his tent, looking over his Masonic orders and paraphernalia, and, on my breaking the news to him as quickly as I could, he said, “Good God! I forgot all about it. Shout for my pony, like a good chap.” I also got a change of ponies. Kaffirs were sent out in all directions to call in the men who were drilling, many of them miles away. As soon as the ponies were ready, we jumped on, Lonsdale saying, “You take that way; I'll take this”, and we went off at a gallop. We had scarcely parted company when Lonsdale's pony shied at something and threw him off. I saw the fall. He appeared to have struck his head and then, rolling over on his back, lay quite still with one of his arms projecting in the air at right angles to his body. I got off at once and ran to his assistance, only to find that he was unconscious, and rigidly stiff. I shouted for the doctor, and as soon as he had come up with some natives and a stretcher, I galloped off again to collect the men. Eventually, after a real race for it, everybody was got in; but Hamilton-Browne and Cooper were still getting their Battalions formed up on parade when the General and staff made their appearance.

I had, of course, to ride out and tell the General what had happened. So we first went to Lonsdale's tent, and finding that he was still unconscious, orders were given for his removal to Helpmekaar hospital. It was found afterwards that he had received concussion of the brain. Through his interpreter, he expressed his pleasure at what he had seen, and gave some sound advice on matters of discipline, especially behaviour towards women and children and prisoners.

On the following day we moved to Rorke's Drift, where Major Black, of the 2nd Battalion, 24th Regiment was given temporary command until Lonsdale returned. (1)

Due to his troops being so widely spread, it was not until 6.30 pm that Chelmsford could muster his force about three miles from Isandlwana. In darkness they advanced towards the silent camp and fired several rounds of shrapnel to dislodge any remaining Zulus; at about 9 pm they reoccupied the corpse-strewn position. The Zulus had gone; there were no survivors from the 1,350 men left there that morning. Worse was to come: Chelmsford's attention was drawn to the distant glow of fire at the British camp seven miles distant at Rorke's Drift. Zulu camp fires could be seen in the nearby hills, and Chelmsford's weary force settled down in a position of all-round defence, expecting an attack at any time.

Private Houseman of the 2/24th Regiment wrote home and his letter clearly identifies the feelings of the surviving soldiers:

I have terrible news to tell you, on 22 all our 1st Bn of Regt were cut up [words missing].

We have lost 200 men and officers.

They surrounded the camp and took everything that we had, we are quite naked. We took and fought our [words missing] at night and killed thousands of their [words missing].

They cut open terrible, we kept tumbling over our poor fellows all cut open from their throat down. We are keeping our own [words missing]. We are making sacks to put on our backs.

They burnt all [words missing] destroyed – it is horrible to think of it.

Everything we had, money and all, we are quite helpless, they took all our rations and ammunition.

Write back at once and direct. T Houseman 2/24th Regt. Zululand, South Africa.

God Bless you all, Amen.

You have heard no doubt of the news in the papers. Out of one company we lost 91 men, 3 got away only. (2)

Just before dawn, Chelmsford's exhausted force moved out of Isandlwana towards Rorke's Drift, which had been left with ‘B’ Company 2/24th. Shortly afterwards they learned that the outpost, with its 8 officers and 131 soldiers under the command of Lieutenant John Chard RE, had survived a night of Zulu attacks. The Zulus at Rorke's Drift had probably intended to make one last attack on the outpost at dawn, but to their sheer disbelief saw Chelmsford's column advancing out of the mist. This caused them much confusion, as they believed the whole of Chelmsford's force had been destroyed. The Zulus abandoned their attack on Rorke's Drift and wearily made their way back into Zululand. Eleven Victoria Crosses and five Distinguished Conduct Medals were later awarded for the defence of the outpost.

Chelmsford paused at Rorke's Drift before setting off to Pietermaritzburg to explain to a startled world how the Zulus had defeated him. By this time, even Chelmsford must have realised the extent of his own luck. But for his splitting of the force on the 22nd, thus precipitating the Zulu attack, the whole column would most likely have been annihilated. Had the Zulus been able to attack the whole force on the following dawn, as they had originally intended, the unprotected camp with the full sleeping force of 5,000 British troops under canvas would have stood little chance against 25,000 charging Zulus.

The Isandlwana Court of Inquiry – blaming Durnford

Of course I know that a dead set was made against your brother. Lord Chelmsford and staff, especially Colonel Crealock tried in every way to shift the responsibility of the disaster from their own shoulders onto those of your brother. (3)

The dust had hardly settled on the carnage of Isandlwana when Colonel Durnford was cast as the prime scapegoat, as the above letter to his brother shows. Within days of the defeat, several damning memoranda had been written:

a. Lord Chelmsford's Order Book dated Wednesday, 22 January 1879: ‘Camp entered. No wagon laager appears to have been made. Poor Durnford's misfortune is incomprehensible’.

b. Major Francis Grenfell, one of Lord Chelmsford's staff officers who was still in Natal on the day of the battle wrote to his father: ‘The loss of the camp was due to [the] officer commanding not Colonel Pulleine, but Colonel Durnford of the Engineers who took command after the action had begun and who disregarded the orders left by the General’.

c. On 27 January, five days after the battle, Sir Bartle Frere was advising the Colonial Secretary in London: ‘In disregard of Lord Chelmsford's instructions, the troops left to guard the camp were taken away from the defensive position they were in at the camp, with the shelter which the wagons, parked [laagered] would have afforded’. And a few days later, ‘It is only justice to the General to note that his orders were clearly not obeyed on that terrible day at Isandlwana Camp’. (4)

Following the British defeat at Isandlwana, Lord Chelmsford convened a Court of Inquiry that met on 27 January 1879 at Helpmekaar, just ten miles from Rorke's Drift. The Court President was Colonel F.C. Hassard, with Lieutenant Colonel Law RA and Lieutenant Colonel Harness RA as Court members. Harness was a crucial witness to events but he was prevented from giving evidence to the Inquiry by Chelmsford, who insisted on his inclusion amongst the jurors. Colonel Glyn, another vital witness, was not permitted to attend or give evidence. The nature of the Inquiry was most unusual when compared with standard military procedure; the court's brief was merely to ‘enquire into the loss of the camp’. Although a number of officers and men had been required to make statements after their escape from Isandlwana, the Court only recorded the evidence of Majors Clery and Crealock, Captains Essex, Gardner, Cochrane, Curling and Smith-Dorrien, and NNC Captain Nourse. It was subsequently argued, within the army and by the press, both in the UK and South Africa, that insufficient evidence was heard, in order to divert blame away from Chelmsford. Harness was later to defend himself by stating, ‘I am sorry to find that it is thought more evidence should have been taken. Of course, I know Lord Chelmsford thought so, for he sent an order that it should be done; but he does not know, nor does the general public know, that a great deal more evidence was heard, but was either corroboratory of evidence already recorded or so unreliable that it was worthless’. He also wrote that, ‘It seemed to me useless to record statements hardly bearing on the loss of the camp but giving doubtful particulars of small incidents more or less ghastly in their nature’. The final line of his report indicated his defensive attitude: ‘The duty of the Court was to sift the evidence and record what was of value: if it was simply to take down a mass of statements the court might as well have been composed of three subalterns or three clerks’. (5)

As author Ian Knight wrote, ‘Of course, the modern historian is left to ponder by what criteria Harness decided which statements were unreliable and worthless’. (6) A moot point indeed.

Harness saw the Court, at best, as a means of obtaining information about the defeat for Lord Chelmsford. However, it served no real purpose apart from giving Chelmsford time to prepare his explanatory speech before he returned to England to present his case to Parliament. The initial observations of the Court certainly enabled the blame for the British defeat to be laid squarely upon the NNC and Durnford. At the Inquiry Colonel Crealock gave false evidence, stating that he had ordered Durnford, on behalf of Chelmsford, to take command of the camp; this persuasive evidence totally exonerated Chelmsford. With regard to the NNC, the Court had heard confusing evidence as to their location and actions on the battlefield, yet they based their findings on the evidence of Captain Essex, who had clearly stated that he did not know their location. The Court declined to listen to several surviving NNC officers who did know.

Durnford was the perfect scapegoat – he was dead. The fact that Durnford was not from an infantry regiment of the line also went against him. He was deemed by the Inquiry to be the senior officer present and therefore responsible, despite the fact that he had explicitly followed orders given to him by Chelmsford. The finding of the Court conveniently accepted, on Crealock's false evidence, that Durnford had been in charge, and accordingly highlighted Durnford's various deficiencies to the point that the Deputy Adjutant General, Colonel Bellairs, forwarded the Court's findings to Chelmsford with the following observation:

From the statements made to the Court, it may be gathered that the cause of the reverse suffered at Isandhlwana was that Col. Durnford, as senior officer, overruled the orders which Lt. Col. Pulleine had received to defend the camp, and directed that the troops should be moved into the open, in support of the Native Contingent which he had brought up and which was engaging the enemy. (7)

Not content with blaming Durnford, Chelmsford's staff then began focusing their attention on Colonel Glyn, Chelmsford's second-in-command, now conveniently isolated from any news at Rorke's Drift. Glyn was sent a number of official memoranda requiring him to account for his interpretation of orders relating to the camp at Isandlwana. Glyn recognised the trap and returned the memoranda unanswered but with the comment, ‘Odd the general asking me to tell him what he knows more than I do’. Glyn finally accepted all responsibility for details, but declined to admit any responsibility for the movement of any portion of troops in or out of camp. The acrimony continued, with Chelmsford even suggesting that it was Glyn's duty to protest at any orders with which he did not agree. Glyn maintained his dignity and his position by stating that it was his duty to obey his commander's orders. Little was said beyond this point; Glyn remained silent and loyal to his General but Mrs Glyn robustly defended her husband in the coming months.

There was no defence for the NNC and no defence for Durnford. Chelmsford finally damned Durnford's reputation in his speech to the House of Lords on 19 August 1880, by stating that:

In the final analysis, it was Durnford's disregard of orders that had brought about its [the camp's] destruction. (8)

It was thereafter widely believed that Durnford had failed to assume command of the camp from his subordinate Pulleine and then irresponsibly taken his men off to chase some Zulus. Most historians' accounts of Durnford's actions at Isandlwana are, at best, uncertain about his orders and the exact sequence of events; or they suppose that Durnford was seeking either to warn Chelmsford of the presence of the Zulus or prevent Chelmsford's force being cut off from their base at Isandlwana. In one of the most famous works on the Zulu war, Major the Hon. Gerald French DSO wrote [his italics]:

As to Lord Chelmsford's orders to Colonels Pulleine and Durnford before leaving the camp on the morning of January 22nd, the evidence adduced before the Court of Inquiry conclusively proved that the former was directed to defend the camp, whilst the latter was to move up from Rorke's Drift and take command of it on his arrival. Colonel Durnford would consequently, on assuming command, take over and ‘be subject to the orders given to Colonel Pulleine by Lord Chelmsford’. (9)

Durnford was now damned beyond redemption. It is probable that we will never know exactly what happened immediately prior to the battle. It is possible that the five surviving British officers' reports were influenced by the nature of the Inquiry. After all, it would have been abundantly clear to these five officers that Chelmsford and his influential staff were doing everything in their power to deflect blame away from Chelmsford and on to others, some conveniently dead. These junior officers were in an obvious predicament, and may well have felt inclined to ‘toe the line’ in support of their General. They were undoubtedly fully aware that their own departure from the Isandlwana battlefield could still be the subject of uncomfortable enquiries. They would certainly have known that Colonel Glyn had been ignominiously relieved of his column duties and transferred to the command of the outpost at Rorke's Drift, thus effectively isolating him from the Inquiry and its aftermath. Despite the possibility of behind-the-scenes pressure on the surviving officers to support their General, Lieutenant Curling nevertheless gave damning evidence of the chaos and confusion at Isandlwana, both before and during the battle. On 28 April he wrote to his mother from the Victoria Club at Pietermaritzburg:

I see they have published the proceedings of the Court of Inquiry: when we were examined we had no idea this would be done and took no trouble to make a readable statement, at least only one or two did so. (10)

Who had command?

Not with standing the decision of the Court to exonerate Chelmsford, it seems right to raise the question – who actually had command at Isandlwana? At first sight, this difficult question appears to have been a matter of some confusion between Durnford and Pulleine. Durnford had requested clarification of the orders he had received the day before, but Chelmsford had not replied. Neither had Chelmsford specifically ordered Durnford to remain, or take charge, at the Isandlwana camp. Having requested clarification, it is probable that Durnford expected to receive fresh orders on his arrival at the camp, yet nothing awaited him. Durnford then set about following his current order to initiate action against Matyana, the chief of the area beyond Isandlwana. It is clear from Lieutenant Cochrane's evidence that Pulleine accepted Durnford's decision to leave the camp, the situation being outside the framework of the orders left to him by Chelmsford. Only Pulleine had orders to ‘defend the camp’. Had Chelmsford intended that the two columns should merge, it is inconceivable that he would not have referred to such an important policy change in his orders.

It was later ‘leaked’ by Chelmsford's staff that Durnford and Pulleine had had words over the issue of taking Imperial troops from the camp, but Cochrane, who claimed he was present, denied that this was so. Durnford's suggestion had been persuasive rather than officious.

Cochrane wrote that Pulleine was apparently distressed when Durnford wanted to relocate two Imperial companies beyond the inlying pickets, yet it is inconceivable that Durnford would have wanted the two infantry companies with him. Slow-moving foot soldiers would obviously have been more of a hindrance than a help to his fast-moving mounted force. It seems more likely that Durnford wished both to strengthen the weak position to the north of the camp and to protect the rear of his mounted men who would be operating on the Nqutu Plateau. Pulleine's concern was apparently shared by some of the camp's officers who felt that the removal of such a large part of the camp's force did not accord with Chelmsford's orders. Cochrane recalled that Lieutenant Melvill, the adjutant of the 1/24th, approached Durnford and said, ‘Colonel, I really do not think Colonel Pulleine would be doing right to send any men out of camp when his orders are to defend the camp’. Durnford replied: ‘Very well, it does not much matter. We will not take them’. (11)

No one knows the objective behind Durnford's request. It must, nevertheless, have been clear to all the officers present, especially Durnford and those of the 24th, that the northern aspect was a blind spot in the camp's defences. After Durnford's departure to intercept the advancing Zulus, two companies of the 1/24th were subsequently dispatched from the camp to the spur to the north, and although the idea for the order could be said to have come from Durnford, Pulleine quite clearly thought it was necessary. In any event, one of the two companies so dispatched was soon overrun by the speed of the Zulu attack; the other just made it back to the camp before it too was annihilated.

Looked at critically, the questions of who was in charge and why Pulleine and Durnford acted as they did are difficult to answer, especially in the light of the Inquiry's deliberations. The truth may never be known, but additional evidence is now available which goes some way towards clarifying the situation. The whole question of Durnford's orders has previously hinged upon the supposition that Durnford received specific orders from Chelmsford. After Isandlwana Chelmsford reproduced, from memory, his recollection of this particular order for his official report and backdated it to 19 January; it is included below, using Chelmsford's remembered words.

Head Quarter Camp

Near Rorke's Drift, Zululand

19 January 1879

No 3 column moves tomorrow to Insalwana Hill and from there, as soon as possible to a spot about 10 miles nearer to the Indeni Forest. From that point I intend to operate against the two Matyanas if they refuse to surrender. One is in the stronghold on or near the Mhlazakazi Mountain; the other is in the Indeni Forest. Bengough ought to be ready to cross the Buffalo R. at the Gates of Natal in three days time, and ought to show himself there as soon as possible.

I have sent you an order to cross the river at Rorke's Drift tomorrow with the force you have at Vermaaks. I shall want you to operate against the Matyanas, but will send you fresh instructions on this subject. We shall be about 8 miles from Rorke's Drift tomorrow.

Chelmsford knew that the actual order had never been found, and no one challenged his account. In 1885, in an extraordinary twist of fate, the Commanding Officer of the Royal Engineers in Natal, Colonel Luard, heard rumours of a cover-up involving the surreptitious removal of Chelmsford's written orders to Durnford from his (Durnford's) body by Shepstone. Luard cautiously advertised his fears in the Natal Witness newspaper and on 25 June 1885 he received the following remarkable reply:

P.M.B. 25 June 85

F. Pearse & Co

14 Cole St.

E.D. Natal Witness Office

Dear Sir

Referring to yr. Advertisement wh. Appeared a few weeks ago in the Natal Witness respecting relics of the late Colonel Durnford. I write to inform you that I have in my possession a document which was picked up by my brother A. Pearse late trooper in the Natal Carbineers. It appears to be the instructions issued by Lord Chelmsford to the late Colonel on taking the field.

I have written to my brother to ascertain whether he is willing to part with it in the event of your wishing to have it in your possession.

Yours truly

(signed) F. Pearse

The weather-stained orders were promptly delivered to Luard. They were in two parts: the first was Chelmsford's original order dated 19 January 1879, and it is on this order that Durnford must have based so much of his decision making when he arrived at Isandlwana. The original text is reproduced below (where a word is unreadable, a possible interpretation is shown in bold), and the order leaves little doubt what was in Chelmsford's mind when he wrote it. It differs considerably from Chelmsford's recollection, printed above.

Lieut. Colonel Durnford R.E

Camp Helpmakaar

1. You are requested to move the troops under your immediate command viz.: mounted men, rocket battery and Sikeli's men to Rourke's Drift tomorrow the 20th inst.; and to encamp on the left bank of the Buffalo (in Zululand).

2. No. 3 Column moves tomorrow to the Isandhlana Hill.

3. Major Bengough with his battalion Native Contingent at Sand Spruit is to hold himself in readiness to cross the Buffalo at the shortest possible notice to operate against the chief Matyana &c. His wagons will cross at Rourke's Drift.

4. Information is requested as to the ford where the above battalion can best cross, so as to co-operate with No. 3 Column in clearing the country occupied by the chief Matyana.

By Order, H. Spalding. Major DAAG

Camp, Rourke's Drift 19.1.79

This penultimate order to Durnford precedes the final order received on the morning of the 22nd. The order clearly states that Durnford's column is to cooperate with the central column and that Bengough's battalion, part of Durnford's force, must be ready to move from the border to the Mangeni area of Chief Matyana; his waggons are to accompany Durnford which indicates an imminent rendezvous.

Chelmsford's final orders to Durnford, signed and sent by Crealock, were received by Durnford at Rorke's Drift on 22 January. Because they are so ambiguous, they are reproduced exactly:

You are to march to this camp at once with all the force you have with you of No. 2 Column.

Major Bengough's battalion is to move to Rorke's Drift as ordered yesterday. 2/24th, Artillery and mounted men with the General and Colonel Glyn move off at once to attack a Zulu force about 10 miles distant.

Armed with this instruction, which clarified his orders from the General dated 19 January, Durnford's mind was clear. He was not instructed to take command of the camp at Isandlwana; indeed, he was free to use his independent No. 2 Column as he thought fit. On his arrival at Isandlwana and seeing the Zulus approach in force, he had no alternative but to attempt to block Zulu progress towards the camp.

Durnford was clearly ordered to ‘cooperate with No.3 Column by clearing the country occupied by the Chief Matyana’. In essence, Durnford did exactly as he was ordered. At 11.15 am Durnford dispatched Captain Barton, who had been attached to Durnford's column for General Duties, with the remaining two troops of Zikhali's Horse led by Lieutenants Raw and Roberts, to the hills to the north to sweep away those thousand or so Zulus who could be seen there. Barton accompanied Roberts; Captain Shepstone, Durnford's staff officer, went with Raw. At about 11.30 am the rocket battery arrived and Durnford gave them orders to be prepared to move out of camp in fifteen minutes. At 11.45 am Durnford left the camp. He took with him Lieutenant Harry Davis's Edendale troop and Lieutenant Alfred Henderson's BaSotho mounted men, the rocket battery under Major Russell supported by ‘D’ Company and the 1/1st NNC under Captain Nourse. Durnford's waggons bringing his ammunition and supplies had not yet arrived, but he must have been confident that the Zulus would not stand and fight. The worst he would have expected was a brief skirmish. This makes sense, as Durnford's highly mobile No.2 Column was ideally placed to drive the Zulus away from the camp.

Trooper A. Pearse discovered these papers on or near Durnford's body while seeking the body of a brother, also a trooper, who had been seen to escape from Isandlwana but then inexplicably to return to collect his bridle, and was never seen alive again. (12) The papers were in poor condition, having been subjected to several months of exposure; at the time of their discovery some parts were so fragile that they could not easily be unfolded or read. The details on the envelope and the location where it was found were clearly sufficient for Pearse to realize that the envelope contained Chelmsford's instructions to Durnford, and in due course Pearse forwarded the papers to the editor of the Natal Witness.

At some point in time, as yet unknown, the envelope and its contents were then forwarded to the Royal Engineers Museum at Chatham. It is possible that Frances Ellen Colenso, the daughter of Bishop Colenso (Anglican Bishop of Natal), sent them to Chatham, as the envelope still bears the initials F.E.C

The second order found on Durnford's body, copies of which had, presumably, been sent to all the Column commanders, relates to the specific tactics to be used when engaging Zulus and is dated 23 December 1878. Whilst it is not relevant to the present argument, the fact that Durnford kept it on his person indicates his intention to obey his orders fully. He would still have been smarting from Chelmsford's earlier rebuke and his threatening reminder to obey future orders, following his (Durnford's) unauthorised excursion across the border with Zululand. The full order is reproduced in Appendix F.

The discovery of the evidence he was seeking galvanised Luard into action, and he wrote a remarkable letter to Sir Andrew Clarke, Head of the Corps of Royal Engineers in which he indicated his view that he could vindicate Durnford. The whole letter is reproduced unabridged and uncorrected in Appendix G.

The result was that Shepstone finally agreed to attend a new Court of Inquiry. The Acting High Commissioner in South Africa was quick to see the implications for Chelmsford and wrote to Luard before the Court was convened at the end of April 1886, ‘I have taken measures to limit proceedings and to prevent, I trust, the possibility of other names, distinguished or otherwise, being dragged into it’. (13)

When the Inquiry commenced, it was, curiously, limited to the investigation of whether or not papers had been removed from Durnford's body. Various important witnesses were refused leave to attend by the army or the civil authorities, and Luard's case crumbled. Shepstone was cleared and Luard was obliged to apologise to him. And there the matter rested.

In June 1998, a report made by Captain Stafford of the NNC came to light. This report was written in 1938, when Stafford was in his late seventies, and records his memory of the battle at Isandlwana, where he was one of Durnford's staff officers. Two interesting points are made by Stafford. Firstly, his account of the initial meeting between Durnford and Pulleine reveals that Durnford was concerned at Pulleine's disposition of the troops so far from the camp. Stafford wrote:

Col. Durnford and Capt. Shepstone entered Pulleine's tent whilst I remained outside. From what I could hear, an argument was taking place between Pulleine and Durnford as to who the senior was. Col. Pulleine appeared to give way and I heard Durnford say, “You had orders to draw in the camp”. Alas there was no time for this as the fighting had already commenced. I can never understand to this day why this was not done. (14)

Secondly, Stafford relates how Durnford deployed his force to stem the advance of the main Zulu force. It would appear that Durnford was anticipating the camp being attacked and acted accordingly. Stafford records how the Zulus advanced at speed and forced Durnford's men back towards the camp. This was with the exception of Lieutenant Roberts of Pinetown who had managed to get his men into a cattle kraal on the edge of a ridge. Stafford subsequently heard that Roberts and his men had been shelled by British artillery and that Roberts met his death as the result of this ‘friendly fire’.

Pulleine now faced the rapidly approaching Zulu army; it was too late to react, the troops were deployed too thinly and too far from the camp. His total misunderstanding of Zulu tactics ensured their victory, as did Pulleine's deployment of his manpower so far away. The reason, as seen from the missing orders, was because he was obeying to the letter the orders he had received from Chelmsford, orders given to all five Column commanders which detailed the tactics to be used in the event of a Zulu attack. If further evidence is required, then it should be pointed out that identical tactics had coincidentally been used that very same morning on two separate occasions: only fifty miles from Isandlwana at Nyzane, where Colonel Pearson's Coastal Column came under a sustained Zulu attack, and by Colonel Wood during a skirmish at Hlobane. Pulleine had no battle experience and faithfully deployed his force according to Chelmsford's orders. Such tactics were doomed to fail in a defensive position. They were never used again against the Zulus.

Was there a conspiracy to blame Durnford? Perhaps not intentionally, but after Durnford's death circumstances appear to have conspired against him. Chelmsford initiated the Court of Inquiry, and its terms and purpose were, at best, curious. Certainly Crealock deliberately lied when he told the Court that he had issued orders to Durnford to ‘take command of it’ (the camp), when in fact this was not the case. The Court's findings enabled Chelmsford to escape the blame, and his account to the House of Lords relied on those findings to pin the blame on Durnford. Sadly, Chelmsford always stood by his report to Parliament and joined his staff in their attempt to blame Glyn – but this tactic backfired when Glyn defused the accusation by accepting partial blame.

At last there is sufficient evidence to prove that Durnford behaved correctly and bravely in following his General's faulty orders. His reputation should now be seen in the same light as his military record, which was exemplary. Incidentally, it is known that Durnford's daughter moved to South Africa and subsequently married a local farmer, whose name is not recorded.

On 28 March 1880 Sir Charles Dilke, MP for Chelsea, spoke in Parliament of:

The gallant fellows who fell in that miserable affair at Isandlwana – 53 officers and nearly 1,400 men – through the gross incompetence of a General upon whose head rests the blood of these men until he has been tried by Court Martial and acquitted.

Lord Chelmsford's orders to Column commanders

A modern examination of these long-lost documents confirms that both Pulleine and Durnford obeyed Chelmsford's orders fully. It is also evident that, after Isandlwana, Chelmsford's written orders that Durnford received on the day of battle were ambiguously ‘re-worded’ by Crealock to vindicate Chelmsford and his staff and to incriminate Durnford. One must presume that Chelmsford's staff believed that the actual orders had been destroyed; indeed, there has been no trace of these latest orders until recently.

Among the papers found on Durnford's body was his personal copy, as commander of No. 2 Column, of Chelmsford's General Orders; these relate to the specific tactics to be used when engaging the Zulus and are dated 23 December 1878. These orders may well have been re-issued, because the previous ‘1878’ orders were generally disregarded and were mockingly known as ‘Bellairs Mixture’, a combination of the Deputy Adjutant General's name with that of a popular patent medicine. Presumably these same new orders were sent to all of the five Column commanders, because they referred to the tactics to be used in anticipation of a Zulu attack. It is these orders that may now answer the question that has baffled historians since Isandlwana: why did Pulleine deploy his manpower so far from the camp?

These orders, found on or near Durnford's body, were hand-written and signed by Chelmsford. They are dated Monday, 23 December 1878 and must, therefore, have replaced Chelmsford's original Regulations for Field Forces in South Africa 1878. They are reproduced in Appendix F in their exact form, using the original, unabridged and grammatically uncorrected text.

A review of the General Orders

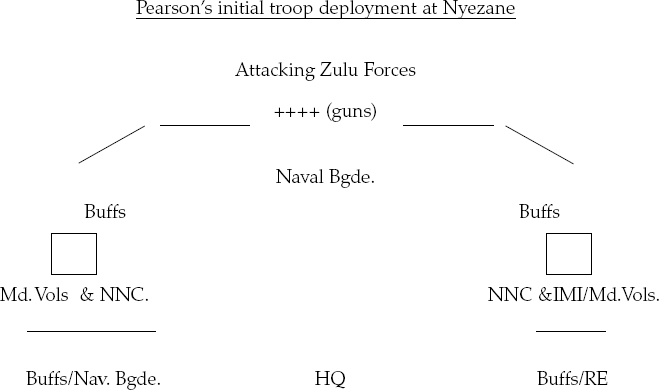

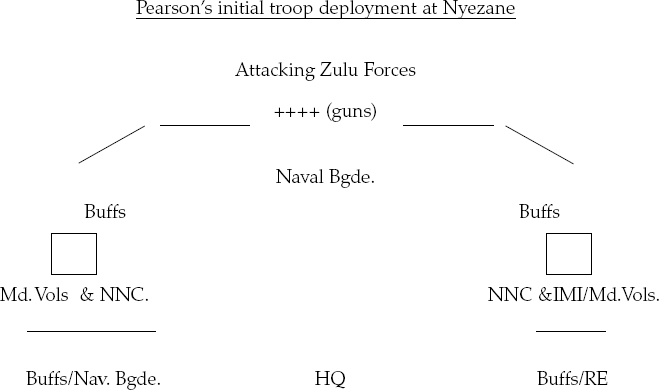

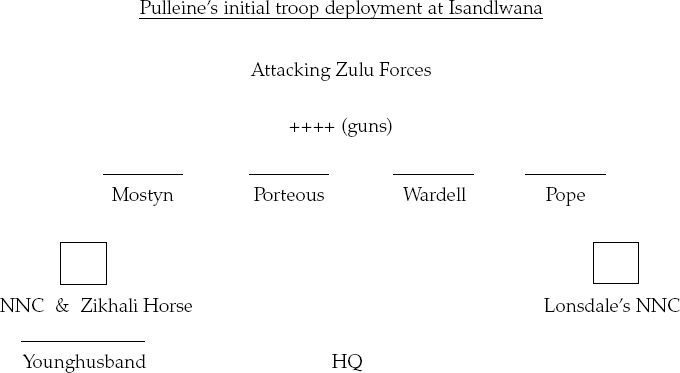

A comparison of item 18 in Chelmsford's Orders with the known Isandlwana line of defence reveals a strong similarity, also seen in Pearson's tactics at Nyezane only a few hours earlier. Presumably to avoid ambiguity, Chelmsford even drew a diagram of his required deployment in the face of a Zulu attack. This is particularly relevant in the light of the similar formations adopted on 22 January at Nyezane and Isandlwana. Furthermore, many writers have discussed the lack of camp defences at Isandlwana; these orders totally omit any reference to prepared defences in camp.

Colonel Pulleine's deployment of his experienced troops in an extended line so far out from the Isandlwana camp was referred to contemptuously by many contemporary writers and has mystified most military historians. Pulleine had no battle experience and had little warning of the impending disaster – yet the deployment was clearly not his own idea. No historian has ever produced evidence that the experienced 1/24th officers ever challenged the extended deployment so far from the camp, although Captain Stafford NNC recalled in his memoirs that when Durnford arrived at Pulleine's tent, Durnford expressed considerable alarm at the distant disposition of British troops. As the senior officer at Isandlwana, it was logical that Pulleine would follow Chelmsford's orders and so he deployed his men according to the plan drawn in these orders. No wonder that the officers of the 24th thus deployed did not openly demur.

A comparison of these orders with the Isandlwana dispositions prior to the Zulu attack reveals a pattern in exact accordance with Chelmsford's orders. Perhaps this is another reason why these orders were never referred to by Chelmsford's staff officers at the subsequent Inquiry, or thereafter. Their publication would have completely vindicated Pulleine. There is a distinct possibility that the five junior officers who survived Isandlwana were unaware of the existence of these orders, which may also account for their previous non-publication. In effect, the distribution of these orders was very restricted and they would have been easy to conceal subsequently.

At exactly the same time as the attack on Isandlwana, Colonel Pearson and his No. 1 Column were advancing into Zululand from near the mouth of the Tugela River. Early on the morning of 22 January 1879, Pearson's Column was attacked near the Nyezane River. Pearson would presumably have made his troop dispositions according to Chelmsford's instructions, i.e. the same instructions issued to Durnford and Glyn (and inherited by Pulleine). There should therefore be some correlation between Pearson's and Pulleine's troop dispositions, at Nyezane and Isandlwana respectively, and Chelmsford's diagram.

Both Pulleine's and Pearson's troop deployments in the face of attacking Zulus (on the very same day but fifty miles apart), as represented above, are too like Chelmsford's orders for the similarity to be coincidental. Bearing in mind the terrain over which Pearson's men were deployed and the fact that the diagram is a simplified version of their disposition, the similarities between his and Chelmsford's deployment order eighteen are plainly visible. Likewise, only two days later on 24 January, Colonel Wood's northern column, forty miles to the north of Isandlwana, dispersed a strong force of Zulus near Hlobane Mountain using identical tactics.

Pulleine had no battle experience and he appears to have faithfully deployed his force according to these orders – orders that the other Column commanders had also received and on which Pearson had similarly acted on the very same day as Isandlwana. The whereabouts of Pulleine's original orders are unknown for certain, although a second set of orders, also taken from the battlefield as a souvenir by a member of the burial party, was discovered in early 2000. These orders are identical to those taken from Durnford's body but have no addressee. Likewise, the whereabouts of the identical orders to the other three Column commanders (Pearson, Woods and Rowlands) are not known. Indeed, there is no known mention, official or otherwise, of these original orders. Clearly, any acknowledgement of them would have been highly embarrassing to Chelmsford and his staff, and there is no known evidence that Chelmsford ever mentioned the existence of these orders in any private or official correspondence. Pulleine's reputation, like that of Durnford, should now be seen in the same light as both their military records, exemplary and beyond reproach.

Perhaps the final word on Chelmsford comes from the War Office. In a memorandum to the Commander in Chief of the Army, the Duke of Cambridge, his Adjutant General Sir Charles Ellice wrote a lengthy but considered overview of the defeat at Isandlwana, after examining all available evidence and reports. His overview ended by making a number of crucial observations, abbreviated below. He wrote:

To this belief in the crushing effect of our weapons and the small probability of the enemy venturing upon a flank attack in the open, is evidently due to the immediate causes of the defeat at Isandlwana, viz.

a. Rorke's Drift had not been put in a proper state of defence before operations commenced.

b. The non-preparation of a defence at Isandlwana either by wagons or building a small redoubt.

c. Departing the camp in the early hours of the 22nd with a significant force leaving the camp defences, notwithstanding that Durnford had been called up.

d. Not searching the north-east knowing there was a large force of Zulus approaching from the east.

e. Not considering the possibility/likelihood of a serious attack on the camp, and

f. Dividing the camp defenders and not creating a laager, or massing the troops in a square with sufficient ammunition. (15)

Several points spring to mind: in item c., Durnford was ordered to reinforce the camp, not to take command. This therefore discredits Crealock's statement that Durnford was ordered to ‘take command’. The final item seems directed at Pulleine, but in his defence Pulleine tried to follow Chelmsford's written orders which were, as it turned out, defective – especially as Chelmsford had ignored all intelligence warnings of the Zulu army's approach.

Recently discovered letters from Lieutenant Curling

In 1998 three bundles of faded letters were about to be discarded when it was realised they related to the Zulu War. They were the letters of Lieutenant Henry Curling RA, the only British officer to have fought on the front line at Isandlwana and survived. These letters provide a fascinating insight into what really happened, as well as casting some doubt on the previously accepted theories of the RA guns' final position after the British defeat. His letters reveal the chilling terror and chaos of Isandlwana as well as the appalling conditions endured by the few survivors:

23rd January 1879

My dear Mama,

Just a line to say I am alive after a most wonderful escape.

In the absence of the General, our camp in Zululand was attacked by overwhelming numbers of Zulus. The camp was taken and out of a force of 700 white men only about 30 escaped. All my men except one were killed and the guns taken. Major Smith who was with me was killed. The whole column has retreated into Natal again and we are expecting hourly to be attacked.

Of course everything has been lost, not a tent or blanket left.

Your aff son

H T Curling

This letter was written the day after the battle, and was entrusted to the officer carrying the official dispatch to Pietermaritzburg, but it probably did not arrive at Curling's home in Ramsgate until early March. The dispatch was telegraphed to Cape Town and carried by special steamer to St Vincent, whence it was telegraphed to London; it arrived in the early hours of 11 February 1879. A Reuters dispatch arrived slightly earlier, their man in St Vincent having persuaded the telegraphist to give his message priority, and reached Mr. Dickinson, the night editor, at 1 am. He rushed it to the newspapers via a fleet of hansom cabs and The Times printed the report in their second edition on the 11th, so Ramsgate probably got the news on the 12th, three weeks after the battle. The report included a list of the officers killed, including Major Stuart Smith, who was known to be a comrade of Curling, so his parents would have been anxious for many days on his behalf.

Curling's next letter home was dated 2 February 1879 and was printed in the Standard on 27 March. This letter is reproduced in Appendix H and confirms his evidence to the Court of Inquiry.

Curling's evidence to the Court of Inquiry

From Lt. Curling to Officer Commanding no 8 [sic – N5?]

Sir,

I have the honour to forward the following report of the circumstances attending the loss of 2 guns of N. Brigade, 5th Battery, Royal Artillery, at the action of Isandala [sic] on January 22nd.

‘About 7.30 a.m. on that date, a large body of Zulus being seen on the hills to the left front of the camp, we were ordered to turn out at once, and were formed up in front of the 2nd Battalion 24th Regiment camp, where we remained until 11 o'clock when we returned to camp with orders to remain harnessed and ready to turn out at a minutes notice. The Zulus did not come up within range and we did not come into action. The infantry also remained in column of coys [companies]. Col. Durnford arrived about 10 a.m. with Basutos and the rocket battery; he left about 11 o'clock with these troops, in the direction of the hills where we had seen the enemy. About 12 o'clock, we turned out, as heavy firing was heard in the direction of Col. Durnford's force. Major Smith arrived as we were turning out, and took command of the guns. We trotted up to a position about 400 yards beyond the left front of the Natal Contingent camp, and came into action at once on a large body of the enemy about 3/4000 yds. off. The 1st. Battn. 24th Regt. soon came up and extended in skirmishing order on the flanks and in line with us.

In about a quarter of an hour, Major Smith took away one of the guns to the right, as the enemy were appearing in large numbers in the direction of the drift, in the stream in front of the camp.

The enemy advanced slowly, without halting; when they were 400 yards off, the 1st/24th advanced about 30 yards. We remained in the same position. Major Smith returned at the time with his gun, and came into action beside me. The enemy advancing still, we began firing case, but almost immediately the infantry were ordered to retire. Before we could get away, the enemy were by the guns, and I saw one gunner stabbed as he was mounting on to an axle-tree box. The limber gunners did not mount but ran after the guns. We went straight through the camp but found the enemy in possession. The gunners were all stabbed going through the camp, with the exception of one or two. One of the two Sergeants was also killed at this time. When we got on to the road to Rorke's Drift, it was completely blocked by Zulus. I was with Major Smith at this time, he told me he had been wounded in the arm. We crossed the road with the crowd, principally consisting of natives, men left in camp and civilians and went down a steep ravine leading towards the river.

The Zulus were in the middle of the crowd, stabbing the men as they ran. When we had gone about 400 yds. we came to a deep cut in which the guns stuck. There was, as far as I could see, only one gunner with them at this time, but they were covered with men of different corps clinging to them. The Zulus were in them at once and the drivers pulled off their horses. I then left the guns. Shortly after this I saw Lt. Coghill, who told me Col. Pulleine had been killed.

Near the river I saw Lt. Melvill, 1/24th, with a colour, the staff being broken.

I also saw Lt. Smith-Dorrien assisting a wounded man. During the action, cease firing was sounded twice.’

I am, etc.,

H.T. Curling, Lt. RA

The crux of the difference between Curling's version and that accepted by modern historians is that the latter believe that the horses and limbers plunged into a transverse donga beside Black's Koppie, whereas Curling consistently maintained that the guns ran along the rocky ground for some 400 yards and then stuck. Lieutenant Milne RN, Chelmsford's naval liaison officer, recorded in his Report on Proceedings, 21st-24th January, 1879, ‘There is a report that one gun was seen to tumble into a nullah but whether it was spiked or not is not known’. Lieutenant Cochrane's report, published in the London Gazette on 21 March, can be interpreted either way:

The guns moved from left to right across the camp and endeavoured to take the road to Rorke's Drift: but finding this in the hands of the enemy, turned off to the left, came to grief in a ‘Donga’, and had to be abandoned.

The Court of Inquiry's evidence is suspect because Lieutenant Colonel Harness, one of the Court's three members, insisted that it should not express an opinion. He also stated that a lot more evidence was heard, but was ignored in the record as being repetitive or worthless (Harness had arrived at Helpmekaar on 24 January and doubtless interviewed Curling at length before his evidence was recorded on the 26th. The Court opened on the 27th). All concerned from Chelmsford downwards had a vested interest in putting the best possible interpretation on the sorry story. Curling's evidence may have been considered too damaging to record in full, knowing it would subsequently be open to thorough examination.

Lieutenant Smith-Dorrien later wrote:

I came on the two guns which must have been sent out of camp before the Zulus charged home. They appeared to me to be upset in a donga and to be surrounded by Zulus. I caught up Curling and spoke to him, pointing out that the Zulus were all around, and urging him to push on, which he did. (16)

The strongest support for Curling's version of events is to be found in Captain Essex's evidence to the Court of Inquiry, written at Rorke's Drift on 24 January and handed in on or after the 27th:

The retreat became in a few minutes general, and in a direction towards the road to Rorke's Drift. Before, however, we gained the neck near the Isandula Hill, the enemy had arrived on that portion of the field also, and the large circle he had now formed closed in on us. The only space which appeared opened was down a deep gully running to the South of the road, into which we plunged in great confusion. The enemy followed us closely and kept up with us, at first on both flanks, then on our right flank only, firing occasionally, but chiefly making use of the assegais. It was now about 1.30 p.m.: about this period, 2 guns with which Major Smith and Lt. Curling R.A. were returning with great difficulty, owing to the nature of the ground, and I understood were just a few seconds late. Further on, the ground passed over on our retreat would, at any other time, be looked upon as impractical for horsemen to descend, and many losses occurred, owing to horses falling, and the enemy coming up with the riders: about half a mile from the neck, the retreat had to be carried on in single file, and in this manner, the Buffalo river was gained at a point about 5 miles below Rorke's Drift. (17)

It is perhaps significant that Curling wrote after his return to the battlefield in May that the gun limber was ‘just where I left it’. Curling was not in command, and wrote on 2 February 1879 that Smith's return ‘of course relieved me of all responsibility as to the movement of the guns’. Hence, apart from any loyalty to a dead brother officer, he was almost in the position of an impartial observer. And though Smith was wounded before the retirement, he was still able to do his duty up to the time he was killed near Fugitives' Drift. Lieutenant Smith-Dorrien recalled that whilst he was tending a wounded man there, there was a shout, ‘Get on, man, the Zulus are on top of you’! Smith-Dorrien continued:

I turned round and saw Major Smith RA who was commanding the section of guns, as white as a sheet, and bleeding profusely; and in a second we were surrounded, and assegais accounted for poor Smith, my wounded MI [mounted infantry] friend and my horse. With the help of my revolver, and a wild jump down the rocks, I found myself in the Buffalo River. (18)

Apart from the question of the exact point where the guns were abandoned, Curling's report and letters are certainly consistent. It is not surprising that the Inquiry disregarded his evidence, as his account confirmed Pulleine's inability, probably as a result of his lack of fighting experience, both to prepare for the Zulu attack and then to take appropriate measures to counter it. On 28 April Curling wrote to his mother from the Victoria Club, Pietermaritzburg:

I am sorry to say our column is still to be commanded by the General [Lord Chelmsford]. I feel these disasters have quite upset his judgement or rather that of his staff and one does not feel half so comfortable under his command as with a man like Col. Wood. Our column is likely to be the one that will have all the fighting.

Indeed, Chelmsford formally sought to be returned to the UK on the grounds of ill health. On 9 February 1879 he wrote:

In June last I mentioned privately to His Royal Highness The Duke of Cambridge, Commander in Chief, that the strain of prolonged anxiety and exertion, physical and mental was even then telling on me – What I felt then, I feel still more now. (19)

The Standard was moved to write:

No such appeal to the Authorities of England for dismissal from a position to which Lord Chelmsford felt himself unequal had ever before been addressed to them by a General in the field commanding Her Majesty's troops. (20)

He was not replaced until after the Battle of Ulundi on the 4th July 1879.

Curling moved to Wesselstrom in the Transvaal early in October 1879 where he remained until the end of November. He was promoted Captain and posted to a battery in ‘Caubul [Kabul] – in time to earn another medal’. He had hoped that he would be able to secure home leave before sailing to India, but it was not to be, and in a letter dated 25 January 1880 from Pinetown he wrote that he expected to sail for India and the Afghan war on 4 February.

After the Afghan war, Curling served in India and at Aldershot, and in 1896 was Lieutenant Colonel OC RA in Egypt. He retired to Kent, where he became a respected Justice of the Peace; he never spoke of Isandlwana.

Re-formation of the 1st Battalion 24th Regiment and the sinking of the Clyde

As soon as tidings of the disaster at Isandlwana reached England, volunteers were called for to re-form the First Battalion, and a draft of 520 non-commissioned officers and men was furnished by the following units: 1st battalion 8th, 1st battalion 11th, 1st battalion 18th, 2nd battalion 18th, 1st battalion 23rd, 2nd battalion 25th, 32nd, 37th, 38th, 45th, 50th, 55th, 60th, 86th, 87th, 103rd, 108th, and 109th. When they collected at Aldershot, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel H.F. Davies of the Grenadier Guards, most of the men were raw recruits and many had never fired a Martini-Henry rifle. The draft embarked at Woolwich, in the Clyde, on 1 March 1879; Captains Brander and Faraquhar Glennie and Lieutenant T. J. Halliday, 24th Regiment, and a number of special service officers proceeded with the draft.

The Clyde had an uneventful voyage until 4 April 1879, when she ran upon a reef seventy miles east of Simon's Bay, between Dyer's Island and the mainland. The sea was perfectly smooth at the time, and the troops were all got safely on shore by 11.30 am, except for two companies which were left on board two hours longer to look after the baggage. These companies had not long landed when, with the rising of the tide, the ship slid off the reef and suddenly went down, all clothing, books and other personal property in her being lost. The chief officer of the Clyde had previously been dispatched to Simon's Bay, where he arrived at 10 pm the same night, and early on the morrow the Tamar arrived, took the draft on board, returned to Simon's Bay and on 7 April started for Durban, arriving there on the 11th. The troops were at once landed and marched up country, reaching Pietermaritzburg on 18 April, Ladysmith on 29 April, and Dundee on 4 May.

At Dundee the 1st Battalion was re-formed with ‘D’ and ‘G’ companies 1/24th, which had remained at Helpmekaar, under command of Brevet Major Russell Upcher.

The acting officers of the re-formed battalion were:

Brevet Lieutenant Colonel W. M. Dunbar, commanding.

Major J. M. G. Tongue. Acting-Major Wm. Brander.

Captains Brevet-Major Russell Upcher (A company), Rainforth, (G company), A. A. Morshead (B company), L. H. Bennett (D company), Hon. G. A. V. Bertie, Coldstream Guards (E company).

Lieutenants W. Heaton, (F company), C. R. W. Colville, Grenadier Guards (C company), R. A. P. Clements, (Acting Quartermaster), Weallens, W. W. Lloyd.

Sub-Lieutenants W. A. Birch, J. D. W. Williams, W. C. Godfrey, M. E.

Carthew Yorstoun, Robt. Scott-Kerr, R. Campbell, Hon. R. C. E.

Carrington. Captain C. P. H. Tynte, Glamorgan Militia, Lieutenant St. Le Malet, Dorset Militia, Lieutenant E. P. H. Tynte, Glamorgan Militia, E. R.

Rushbrook, Royal East Middlesex Militia, Second Lieutenant Lumsden, 2nd Royal Lanarkshire Militia.

On 13 May 1879, the reconstituted 1/24th, again under the command of Colonel Glyn, marched to join Major General Newdigate's division, and on 7 June was formed into a brigade with the 58th and 94th regiments, under Colonel Glyn. The brigade marched towards Ulundi, and on 27 June arrived within ten miles of the Zulu capital. Leaving two companies in laager at Entonganini, the remainder of the battalion advanced with its division, carrying ten days' rations and no tents, towards Umsenbarri; they joined General Wood's column, and formed laager and built a stone fort, Fort Nolela, on the banks of the Mfolozi. All the mounted men, including the mounted infantry under Lieutenant and Local Captain E. S. Browne, 24th Regiment, crossed the river and reconnoitred as far as Ulundi. In the battle which followed there, Glyn's brigade was present, with the exception of the 1/24th, which Chelmsford considered to lack any battle experience and left in the entrenched camp on the Umvolozi, under Colonel Bellairs. On 4 July, the Zulu power now being regarded as broken, the brigade retraced its steps to Entonganini, where it lay during the great storm of wind and cold of 6 July 1879. It subsequently returned to Landman's Drift.

On 26 July the battalion received orders to march back to Durban and embark for England. Moving by Dundee, Greytown, and Pietermaritzburg to Pine Town, it encamped, and there, at a brigade parade on 22 August 1879, the Victoria Cross was presented to Lieutenant E. S. Browne, ‘H’ (late ‘B’) company, having rejoined from St. John's River. The battalion, under command of Colonel Glyn, numbering 24 officers, 46 sergeants, 36 corporals, 11 drummers and 767 privates, then embarked in the transport Egypt on 27 August, landed at Portsmouth on 2 October, and marched into quarters in the New Barracks, Gosport.

Many of the surviving ‘D’ Company (Upcher) and ‘B’ Company (Rainforth) 1/24th soldiers found it difficult to mix with the new recruits and, once back in England, most of the recruits chose to return to their original regiments rather than remain as 24th soldiers.

Mental health of British soldiers in Zululand

Following Isandlwana, a number of soldiers fell victim to stress and anxiety – today known as post-battle fatigue syndrome and post-traumatic stress. Such soldiers were gathered into groups and, often in handcuffs, repatriated to Britain for distribution to mental homes or to the care of their families. One group of about thirty such souls was collected at Durban to await embarkation on a UK-bound troopship. The men were transferred by lighter to the ship, but before the accompanying orderlies could board, a storm blew up and the ship was forced to sail without them. Some panic ensued in port, and the orderlies were sent overland to meet the ship at Capetown.

On board, the returning soldiers took pity on the ‘inmates’, and following much exchanging of uniforms, the inmates mingled among the hundreds of healthy soldiers. The captain, aware of events, formed a board of NCOs to trace the inmates. They failed. When the ship docked at Durban, it was impossible to differentiate between the two groups and no further action was taken. The ship sailed on to England without the orderlies.